December 19th, 1944.

If General George Smith Patton hadn’t turned his entire army 90° north in 72 hours, 10,000 United States paratroopers would have been annihilated in the frozen forests of Belgium.

Not captured, not forced to surrender, anyhillated.

The man they called old blood and guts was about to attempt something that every military expert in the European theater said was operationally impossible.

German commanders were so confident in their assessment that they told Adolf Hitler the surrounded United States forces would be crushed within 48 hours.

They didn’t know they were about to face the most aggressive general in the history of modern warfare.

This is the story of how General George Smith Patton did the impossible and why German field marshals would later call it the greatest military maneuver they had ever witnessed.

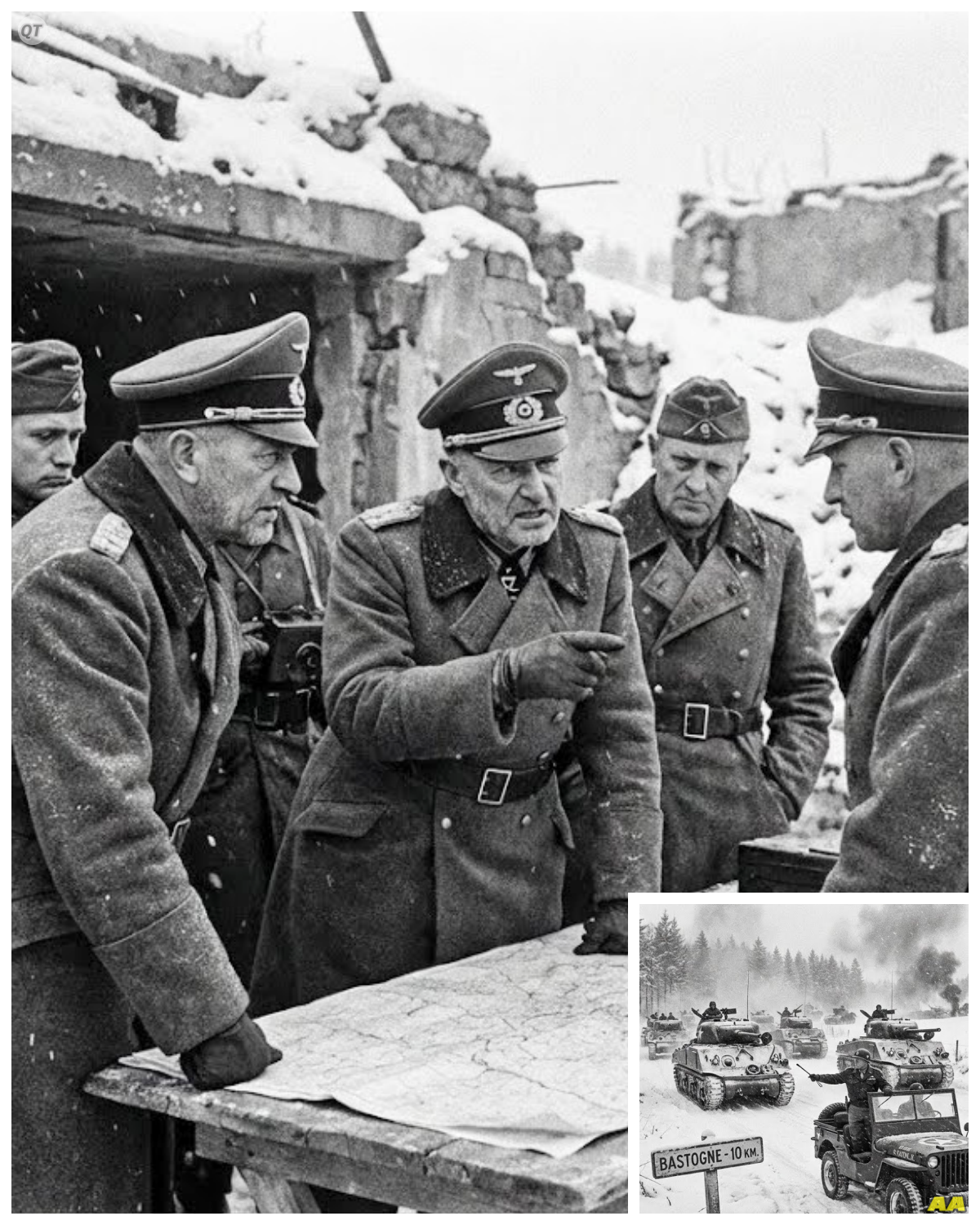

The morning of December 16th, 1944 had begun with an earthshattering roar.

Over 200,000 German soldiers supported by more than a thousand tanks smashed through a thinly defended section of the Allied lines in the Arden’s forest.

Adolf Hitler had gambled everything on one massive surprise attack code named Operation Waktam Rin.

His objective was simple and devastating.

Split the Allied armies, capture the vital port of Antworp, and force the British and United States forces to negotiate a separate piece.

The attack hit with the force of a sledgehammer, catching Allied intelligence completely offg guard.

Within 72 hours of the initial assault, the situation had transformed from surprise to catastrophe.

The 101st Airborne Division along with elements of the 10th Armored Division and other United States units found themselves completely surrounded in the small Belgian crossroads town of Bastona.

Seven roads converged on this otherwise insignificant market town, making it the key to the entire region.

Whoever controlled Baston controlled movement throughout the Ardens.

The Germans knew it.

The Allies knew it.

And now 10,000 United States soldiers were trapped there with dwindling ammunition, no air support due to terrible weather, and German Panzer divisions closing in from every direction.

At Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force, the mood was grim.

Maps showed a massive bulge driven deep into Allied lines.

a bulge that threatened to tear apart months of careful planning and potentially extend the war by another year.

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery was calling for a retreat to consolidate defensive positions.

Other generals were talking about strategic withdrawals, regrouping, and counterattacking in the spring.

The winter weather made large-scale operations nearly impossible, they argued.

The roads were covered in ice.

Visibility was near zero.

Moving an entire army across frozen terrain in days rather than weeks.

The professional staff officers shook their heads.

It couldn’t be done.

But they hadn’t asked George Smith Patton.

Old blood and guts earned his nickname through two decades of leading from the front.

Charging into battle while other generals commanded from the safety of rear headquarters.

He wore pear-lled revolvers on his hips, not for show, but because he believed a commander should be ready to fight alongside his men at any moment.

His speeches to his troops were legendary, filled with profanity and promises of violence against the enemy that would make other generals blanch.

The soldiers loved him for it.

They knew that when old blood and guts said he would be there, he meant it.

He had proven it in North Africa, in Sicily, and across France.

Now, as his third army of the United States was driving toward Germany itself, he was about to face his greatest challenge.

The weather was apocalyptic.

Snow fell in thick sheets driven by howling winds that reduced visibility to less than 50 ft.

The temperature had plunged well below freezing, and forecasters predicted it would only get worse.

Roads that had been muddy quagmires just weeks before were now sheets of ice hidden beneath fresh snow.

Tank treads struggled for traction.

Trucks slid off roads into ditches.

Soldiers wrapped themselves in every piece of fabric they could find and still froze during night watches.

This was the worst winter Europe had seen in decades, and armies throughout history had learned that winter was the one enemy that could not be defeated through courage alone.

Inside the perimeter at Baston, the situation was deteriorating by the hour.

Medical supplies were running critically low.

The wounded lay in makeshift hospitals with inadequate shelter from the bitter cold.

Ammunition was being rationed.

Each artillery shell had to count because there might not be another.

Food supplies were reduced to one meal per day.

The men knew what everyone was thinking, but nobody wanted to say out loud.

If relief didn’t come soon, they would have no choice but to surrender or die fighting a hopeless last stand.

But old blood and guts was about to change history.

On the afternoon of December 19th, 1944, General George Smith Patton received the message, “Every field commander dreads.

Report to headquarters immediately for an emergency conference.

” As his command car raced through the snow-covered roads toward the meeting site in Verdun, France, Patton’s mind was already racing ahead.

He knew what they would ask.

He had been watching the situation develop for 3 days.

And while other generals saw catastrophe, George Smith Patton saw opportunity.

The Germans had overextended themselves.

They had driven a salient deep into Allied lines.

But in doing so, they had created a vulnerable position that could be crushed from the sides.

If the United States Army could hit them hard and fast from an unexpected direction, the hunters could become the hunted.

The question was whether anyone would have the audacity to attempt it.

Segment two, the challenge.

5 to 10 minutes.

The meeting room in a cold stone barracks in Verdon was crowded with the highest ranking officers in the European theater.

General Dwight David Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied forces, stood before a large map showing the catastrophic bulge in their lines.

His face was drawn, and those who knew him well could see the weight of command pressing down on his shoulders.

Field Marshall Montgomery was there, as were General Omar Nelson Bradley and a dozen other senior commanders.

The mood in the room was somber, almost ferial.

General George Smith Patton stroed into the room with characteristic confidence.

While other generals wore expressions of concern, old blood and guts looked like a predator that had just spotted wounded prey.

He studied the map for exactly 30 seconds before Eisenhower began speaking.

“Gentlemen, the situation is desperate,” Eisenhower said, his voice tight with controlled tension.

“The Germans have achieved complete surprise and are threatening to split our entire front.

Baston is surrounded.

The 101st Airborne is cut off.

We need options and we need them now.

The room filled with the sound of generals offering cautious proposals.

Pull back here.

Reinforce there.

Wait for the weather to clear before attempting any major operations.

Montgomery suggested a strategic withdrawal to consolidate defensive positions north of the breakthrough.

It was all very reasonable, very professional, and completely inadequate to the scale of the crisis.

Then George Smith Patton spoke.

I can attack on the 22nd of December with three divisions, he said, his voice cutting through the careful deliberations like a knife.

The 26th Infantry Division, the 80th Infantry Division, and the fourth armored division will drive north, break through to Bone, and smash the southern shoulder of the German advance 3 days from now.

The room went silent.

Several generals actually laughed, thinking old blood and guts was making some kind of dark joke to break the tension.

“General Eisenhower studied Patton’s face and realized he was completely serious.

” “George,” Eisenhower said carefully.

“Your Third Army is currently attacking toward the SAR.

You’re facing east.

You’re asking me to believe you can disengage from combat, turn 90°, move more than 100 miles through the worst winter weather in decades, reorient your entire supply system, and attack in 3 days.

That’s correct, Ike.

Patton replied without hesitation.

I already have my staff working on three different plans depending on how many divisions you want me to commit.

I can move with three divisions, four divisions, or six divisions.

Your choice.

But we need to move now.

Field Marshall Montgomery leaned back in his chair with an expression that clearly conveyed his opinion of this proposal.

“That’s quite impossible,” he said in his clipped British accent.

“You’re talking about moving more than a 100,000 men, thousands of vehicles, reorganizing entire supply chains, all while maintaining combat operations.

Even in good weather, such a maneuver would take 2 weeks minimum.

In this weather, a month.

” General George Smith Patton turned to face Montgomery directly.

The difference between us, Bernard, is that I intend to do it and you intend to find reasons why it can’t be done.

The tension in the room ratcheted up instantly.

Other generals shifted uncomfortably.

Eisenhower raised a hand to forestall any argument.

George, I need you to understand something, Eisenhower said, his voice grave.

If you fail, those paratroopers die.

All of them.

10,000 United States soldiers trapped and destroyed because we gambled and lost.

I need absolute confidence from you that this is possible.

Old blood and guts met his commander’s eyes without flinching.

Ike, I’ve already done the planning.

I had my staff draw up contingency plans for exactly this scenario 10 days ago.

My operations officer, Colonel Halley Maddox, has been working around the clock since December 16th.

We have the routes mapped.

We know which units move when.

We know where every supply dump needs to be repositioned.

This isn’t improvisation.

This is calculated audacity.

You planned for this? Bradley asked incredulous.

You planned for a massive German offensive that none of our intelligence predicted.

I planned for the possibility of having to move my army quickly in any direction.

George Smith Patton replied.

That’s what a Third Army commander does.

We stay flexible.

We stay aggressive.

And we never ever assume the enemy will do what we expect.

Eisenhower studied the map again, his fingers tracing the proposed route of attack.

The military professionals in the room were already calculating the impossible logistics.

Three divisions meant approximately 60,000 men.

Add supporting units, supply columns, artillery batteries, tank destroyers, and you were looking at close to 100,000 men and 25,000 vehicles.

They would need to move over roads that were barely passable in good weather through towns and villages where traffic control would be a nightmare, while maintaining radio silence to preserve surprise.

They would need to shift entire supply networks, redirecting fuel, ammunition, and food from moving east to moving north.

They would need to coordinate with air forces that couldn’t fly in the current weather.

They would need to reorganize command structures on the move.

What you’re describing, one staff officer said, shaking his head, is a logistical impossibility.

Moving that many men that distance in that time frame breaks every rule in the book.

George Smith Patton smiled.

The expression of a man who had heard that phrase his entire career.

Good thing I never learned to read that book.

But underneath old blood and guts bravado was something deeper that only those who truly knew him understood.

George Smith Patton had spent his entire life preparing for exactly this moment.

Since childhood, he had studied the great military commanders of history.

He had read everything written about Napoleon, Hannibal, Julius Caesar, and Frederick the Great.

He had learned that the key to victory wasn’t having overwhelming force.

It was having the courage to strike when and where the enemy least expected it.

Speed, aggression, and audacity could accomplish what careful planning and superior numbers could not.

The Germans think we’re paralyzed, Patton continued, warming to his subject.

They think winter and surprise have given them freedom of movement while we sit back and react.

That’s why we hit them now while they’re still confident.

Every hour we wait, they dig in deeper.

Every day we debate, they consolidate their gains.

But if old blood and guts hits them in 72 hours from a direction they’re not defending, we don’t just relieve Baston, we cut off their entire southern flank.

Eisenhower looked around the room at his assembled commanders.

He saw skepticism, doubt, and concern.

Then he looked at George Smith Patton and saw absolute confidence bordering on arrogance.

It was that arrogance that had gotten Patton in trouble before, that had led to controversies and nearly ended his career.

But it was also that same aggressive spirit that had led to victory after victory when more cautious commanders hesitated.

“If I give you the go-ahad,” Eisenhower said slowly, “and you get bogged down or delayed or failed to break through, the entire Third Army could be vulnerable to a German counterattack.

You’d be exposing your flanks, stretching your supply lines, and potentially walking into a trap.

Or, George Smith Patton countered, “Old blood and guts relieves Baston, saves 10,000 United States soldiers, destroys the German offensive, and we’re in Berlin by spring.

Your choice, Ike.

Caution or victory.

” The room held its breath.

This was the decision point.

Play it safe, and the trapped soldiers at Baston would almost certainly be overrun.

take the gamble and risk even greater disaster if Patton failed.

It was the kind of decision that ended careers or made legends.

General Dwight David Eisenhower took a deep breath and made his choice.

All right, George, you have your orders.

Three divisions attack on December 22nd.

Relieve Baston.

God help us all if this doesn’t work.

George Smith Patton snapped to attention and saluted.

I’ll have them out of there before Christmas.

As the meeting broke up, several officers approached Eisenhower privately to express their concerns.

This was too risky.

The timetable was impossible.

Patton was being reckless.

Eisenhower heard them all out and then said something that would be recorded in multiple memoirs years later.

Gentlemen, I agree with everything you’ve said.

By every conventional military standard, what I just authorized is operationally impossible.

But conventional military standards didn’t predict this German offensive and they won’t stop it.

George Smith Patton is the most aggressive combat commander we have.

If anyone can pull this off, it’s old blood and guts.

And if he can’t, then it couldn’t be done.

But could old blood and guts really pull it off? The next 72 hours would tell.

And the German high command was absolutely certain that the answer was no.

When German intelligence officers reported that elements of the Third Army were disengaging in the SAR region and moving north, experienced Vermach generals dismissed it as a local redeployment.

When intercept suggested that multiple United States divisions were on the move, German commanders calculated that it would take at least 10 days for any meaningful force to reach the Bastona area.

They had planned their entire offensive around the assumption that the Allies would need weeks to mount an effective counterattack.

The concept that General George Smith Patton could turn his entire army in less than a week seemed like fantasy.

Operationally impossible, a German field marshal told his staff when asked about the possibility of a relief force reaching Baston quickly.

Even Patton cannot move that fast in this weather.

We have time.

They were about to learn why Old Blood and Guts had become the most feared name in the German military.

On the night of December 19th, 1944, while most of the Allied command structure was still absorbing the shock of the German offensive, George Smith Patton was already executing the most complex military maneuver of his career.

Before the Verdon conference had even ended, his staff officers had sent out coded messages to division commanders throughout the Third Army.

Units currently engaged in combat operations, received orders to break contact with the enemy, and begin moving north.

Artillery batteries that had been registered on German positions for weeks were told to limber up and prepare for displacement.

Supply depots received instructions to begin redirecting hundreds of thousands of gallons of fuel and millions of rounds of ammunition to new locations.

The scale of what Old Blood and Guts was attempting cannot be overstated.

Modern armies don’t turn on a dime.

They are massive, complex organizations with thousands of moving parts that must be carefully coordinated.

Tanks need fuel.

Infantry needs ammunition.

Artillery needs shells.

Everyone needs food, water, and medical support.

Supply convoys must know where to go.

Traffic must be controlled or you get massive jams that paralyze entire divisions.

Communications must be maintained while units are on the move.

And all of this had to happen in the worst winter weather Europe had seen in decades over roads that were barely passable while maintaining enough combat power to defend against potential German attacks on the Third Army’s now exposed positions.

Gentlemen, George Smith Patton told his senior staff on the evening of December 19th, “We are about to do something that military historians will study for the next hundred years.

We’re going to move faster than any army this size has ever moved in winter.

We’re going to maintain complete radio silence until we attack.

and we’re going to smash into the German flank so hard that their great grandchildren will feel it.

Now, let’s get to work.

The Third Army headquarters became a storm of organized chaos.

Maps were spread across every available surface.

Phone lines burned with constant traffic as orders went out to units across a front spanning hundreds of square miles.

Colonel Hi Maddox, Patton’s operations officer, worked with barely 3 hours of sleep over the next 72 hours, coordinating the movement of hundreds of thousands of men.

The planning that had seemed impossible to the generals at Verdon was revealed to be merely extraordinarily difficult when executed by an already prepared staff working for a commander who accepted no excuses.

On the 20th of December 1944, the movement began in earnest.

The 26th Infantry Division, nicknamed the Yankee Division, received orders to march north immediately.

The 80th Infantry Division, which had been fighting in the SAR region, disengaged from combat and began a forced march that would cover over a 100 miles in less than 72 hours.

The Fourth Armored Division, George Smith Patton’s favorite unit and the tip of his spear, began the complex process of moving hundreds of Sherman tanks over icy roads toward a jumpoff position from which they would launch the attack.

The weather was actively trying to kill them.

On the morning of the 20th, temperatures plunged to minus 10° F.

Men who stopped moving for more than a few minutes risked frostbite.

Vehicle engines froze and had to be warmed with blowtorrches before they would start.

Windshields iced over so badly that drivers had to lean out of their cabs to see the road.

Despite all this, the columns kept moving.

Private James O’Hara of the 26th Infantry Division would later write in his memoir, “We didn’t know where we were going or why.

All we knew was that old blood and guts had given an order.

And when that man gives an order, you move.

” We marched through snow so deep it came up to our knees.

We marched all day.

Stopped for a few hours of sleep in frozen ditches, then got up and marched again.

We didn’t complain because we knew General George Smith Patton was up there ahead of us somewhere, driving his staff car right into the teeth of this storm, leading from the front like always.

That image wasn’t propaganda.

George Smith Patton truly was at the front of his army, visiting units on the move, inspecting traffic control points, solving problems as they arose.

When a bridge proved too weak to support heavy armor, Old Blood and Guts was there personally directing engineers to reinforce it while the tanks waited.

When a massive traffic jam threatened to delay an entire division, George Smith Patton himself stood in the middle of an icy crossroads directing traffic until the flow resumed.

His staff begged him to stay at headquarters where he could command effectively.

He ignored them.

“A commander belongs with his troops,” Patton told his chief of staff.

“They need to see old blood and guts out here freezing alongside them.

That’s what leadership means.

” The 21st of December arrived with worse news from Baston.

German forces had tightened their grip on the surrounded town.

The acting commander of the 101st Airborne Division, General Anthony Clement McAuliffe, sent increasingly grim reports.

Casualties were mounting.

Medical supplies were nearly exhausted.

Ammunition for artillery was down to less than 10 rounds per gun.

The weather remained so poor that air resupply was impossible.

McAuliff’s men were fighting off repeated German attacks, but everyone knew it was only a matter of time.

That morning, German officers approached the United States lines under a white flag.

They carried a written surrender ultimatum from the German commander.

The document demanded that General McAuliffe surrender his forces immediately to avoid total annihilation.

The German message stressed that resistance was feutal, that relief was impossible, and that continued fighting would only result in needless casualties.

General Anthony Clement McAuliffe read the surrender demand and gave his famous one-word reply, “Nuts.

” The confused German officers had to have the American slang explained to them.

When they understood that it was a rejection delivered with contempt, they returned to their lines.

The German commander, furious at the refusal, prepared to launch an all-out assault that would crush the defiant Americans.

He was confident that no relief force could possibly arrive in time to save them.

He didn’t know that Old Blood and Guts was ahead of schedule.

By the 22nd of December 1944, three full United States divisions were in position to attack north.

This fact alone was staggering.

George Smith Patton had moved more than a 100,000 men over a 100 miles, completely reorganized his supply network, coordinated with adjacent units to cover his former positions, and prepared detailed attack plans all in 72 hours.

Militarymies had taught that such a maneuver would require 3 weeks minimum.

Patton’s third army had done it in three days.

At 4:45 in the morning, under cover of darkness and still falling snow, General George Smith Patton gave the order to attack.

Artillery batteries that had been hastily imp placed during the night opened fire with everything they had.

The roar of hundreds of guns shattered the frozen dawn.

Infantry divisions moved forward through the snow, rifles at the ready.

Behind them, the Sherman tanks of the fourth armored division rumbled north.

their commanders standing in open turrets despite the bitter cold because visibility was so poor they couldn’t fight buttoned up.

The Germans were caught completely by surprise.

Their intelligence had assured them that the United States third army was still in the SAR over a 100 miles away.

The possibility that General George Smith Patton had turned his entire army and was attacking with three divisions hadn’t even been seriously considered.

When the barrage began, German commanders initially thought it was a local counterattack by isolated units.

Within hours, they realized the horrible truth.

Old blood and guts had done the impossible.

Where did they come from? A captured German officer demanded when interrogated later that day.

“Our intelligence,” said Patton was still attacking toward Sarbuken.

“How is he here? How is this possible?” The answer was simple.

George Smith Patton had planned for the impossible and then executed that plan with ruthless efficiency.

While other generals debated and delayed, old blood and guts had been preparing.

While staff officers calculated that it couldn’t be done, Patton staff had been figuring out how to do it anyway.

This was the difference between caution and audacity, between conventional thinking and military genius.

But the attack was only the beginning.

Between the Third Army’s jumpoff positions and Baston lay more than 20 miles of snow-covered terrain, defended by German units that were now fully alerted and fighting desperately to stop the relief force.

The fourth armored division spearheading the advance ran into fierce resistance almost immediately.

German anti-tank guns positioned in villages and tree lines knocked out Sherman tanks one after another.

Panzer units that had been besieging Baston were redirected south to stop Patton’s advance.

The road to Baston became a grinding battle of attrition that consumed men and machines at an appalling rate.

General George Smith Patton watched the battle develop from a forward observation post.

Binoculars pressed to his eyes as he studied the flow of combat.

His staff officers provided updates on casualty figures and the slow rate of advance.

The fourth armored division was making progress, but at a terrible cost.

Some companies had lost half their strength.

Tanks were burning on the road.

The weather remained atrocious, preventing close air support.

And time was running out for the defenders of Baston.

Keep attacking, Patton ordered.

Old blood and guts doesn’t stop.

We don’t pause.

We don’t consolidate.

We attack until we break through or there’s nothing left to attack with.

This was the essence of George Smith Patton’s military philosophy.

Relentless aggression.

Where other commanders would have paused to regroup, Patton pushed forward.

where conventional doctrine called for consolidating gains before continuing.

Old blood and guts ordered immediate exploitation.

He knew that in war momentum was everything.

Stop moving and you give the enemy time to organize.

Keep attacking and you keep him off balance.

Force him to react instead of act.

Destroy his will to resist through sheer relentless pressure.

The 23rd of December 1944 brought the first break in the weather.

Patches of blue sky appeared through the clouds and within hours, Allied air power was unleashed.

Fighter bombers strafed German positions ahead of the advancing United States forces.

Heavy bombers pounded German supply lines.

Cargo planes finally managed to drop supplies to the besieged garrison at Baston, buying them precious time.

The defenders, who had been on the edge of collapse, found renewed strength knowing that old blood and guts was coming.

Inside Baston, the soldiers of the 101st Airborne Division and supporting units fought with desperate courage.

They knew relief was coming, but they also knew that every hour they held out cost German lives and resources that might otherwise stop that relief force.

Every German tank destroyed at Baston was one less tank opposing the fourth armored division.

Every German infantry battalion pinned down attacking the perimeter was one less battalion defending the approaches from the south.

By the 24th of December, Christmas Eve, the Fourth Armored Division had advanced to within 5 miles of Baston.

5 miles sounds like nothing.

A man can walk 5 miles in less than 2 hours on a good road.

But those 5 mi were defended by some of the best units in the German military, fighting from prepared positions with artillery support and orders to hold at all costs.

The advance became a yardby-yard battle through villages where every building hid an anti-tank gun.

Through forests where every tree might conceal a German soldier with a panzer anti-tank weapon.

General George Smith Patton spent Christmas Eve at the front personally urging battalion commanders forward.

Push them, he told every officer he met.

Don’t let them breathe.

Don’t let them rest.

Old blood and guts is watching and we’re going to break through today.

But Christmas Eve ended with the fourth armored division still short of Baston.

The men who fought that day would remember it as one of the most brutal battles of the war.

Not because of any single dramatic action, but because of the grinding, exhausting, bloody nature of the combat.

Attack a position, take casualties, destroy the defenders, move forward 200 yards, repeat hour after hour in sub-zero temperatures with no rest and no respit.

That night, General George Smith Patton knelt in private prayer.

Something few people knew he did regularly.

Sir, he prayed.

This is Patton again.

I need another miracle.

My men have done everything I’ve asked.

They’ve marched when they wanted to rest.

They’ve fought when they wanted to quit.

They’ve bled for every yard.

Now, I need you to give us one more day of good weather and the strength to finish this.

Old blood and guts doesn’t ask for much, but I’m asking now.

Help us break through.

Whether divine intervention or simply the determination of exhausted men finding one more reserve of strength.

The 25th of December 1944 Christmas Day brought the breakthrough.

Lieutenant Colonel Kraton Abrams commanding a tank battalion of the fourth armored division personally led a column of Sherman tanks in a desperate thrust up a narrow road toward Baston.

German fire was intense.

Tanks were hit and disabled.

Infantry clinging to the tanks were cut down.

But Abrams kept moving, kept firing, kept pushing forward.

At 4:30 in the afternoon, as winter darkness was already falling, Lieutenant Colonel Kraton Abrams lead tank crashed through the German lines and made contact with forward elements of the 101st Airborne Division.

The siege of Bastoni was broken.

The relief force had arrived.

The moment word reached General George Smith Patton, old blood and guts allowed himself a rare smile.

“I told Ike I’d have them out by Christmas,” he said.

Patton keeps his promises, but the battle was far from over.

The corridor linking Baston to the Third Army was narrow and vulnerable.

German forces immediately began attacking from both sides, trying to cut it off again.

What followed was a week of some of the most intense fighting of the entire Battle of the Bulge as George Smith Patton’s forces widened the corridor, reinforced Baston, and then began the grinding work of pushing the Germans back.

This is why they called him old blood and guts.

Not just for his aggressive nature, but for his understanding that battles are won by men who refuse to accept defeat, who push beyond what seems possible, who lead from the front regardless of personal danger.

While other generals managed battles from headquarters bunkers, George Smith Patton was at the front, visible to his men, sharing their dangers, driving them forward through sheer force of will.

German commanders monitoring the battle from their headquarters struggled to understand what had happened.

Their entire operational plan had been based on the assumption that Allied response would be slow, cautious, and predictable.

Instead, George Smith Patton had responded with unprecedented speed and aggression.

The man they had hoped to bypass had instead smashed into their southern flank and torn open their entire offensive.

Only Patton, a captured German general said during interrogation.

Only that madman Patton could have done this.

Any other Allied commander would have needed weeks to mount such an operation.

He did it in days.

We planned for everything except facing old blood and guts.

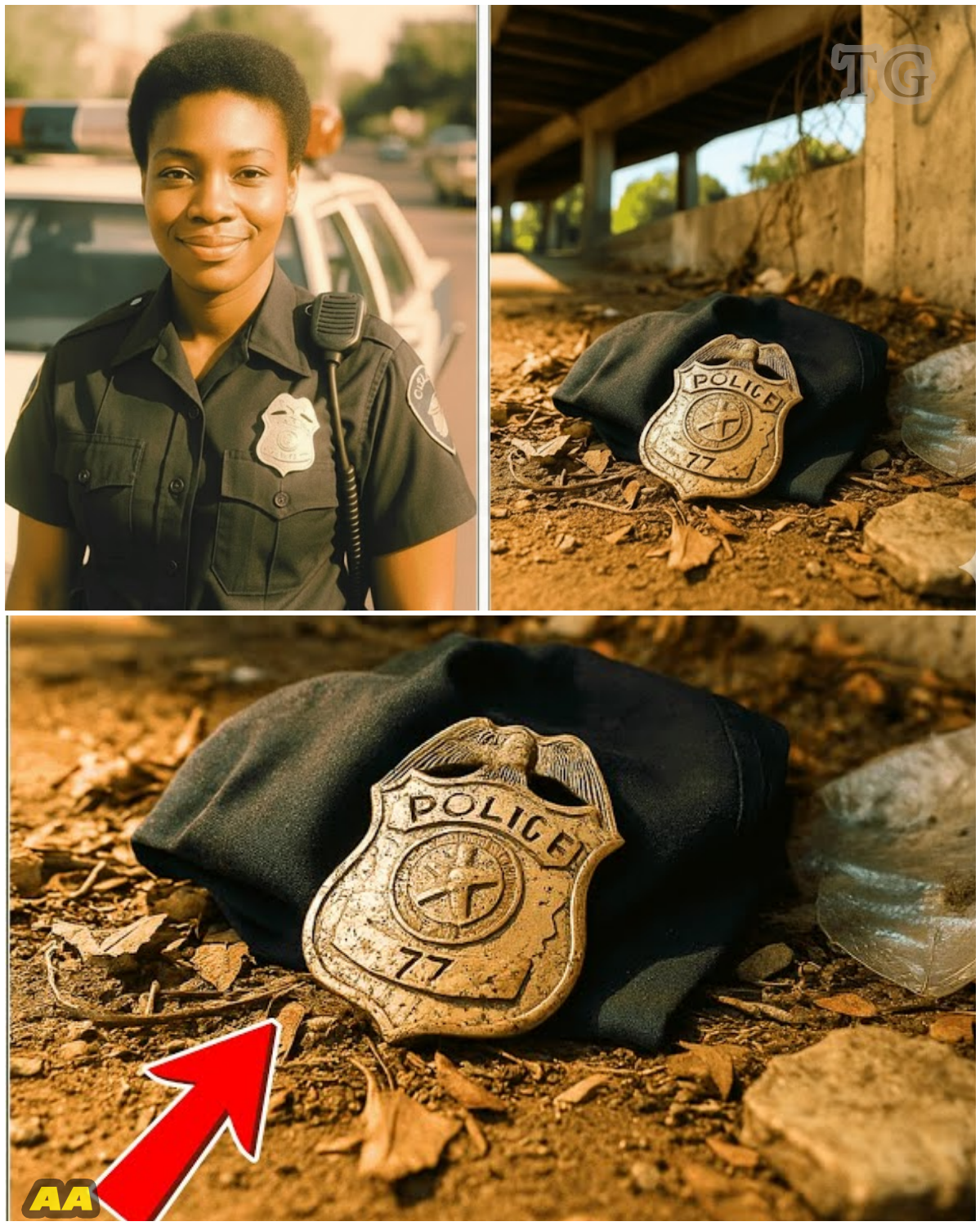

The breakthrough to Baston on December 25th, 1944.

He was not the end of the battle, but the beginning of a new phase that would test every ounce of General George Smith Patton’s tactical genius.

The narrow corridor linking the besieged town to the Third Army’s lines was immediately dubbed the bowling alley because German artillery could hit it from both sides.

United States supply convoys racing up this road took horrific casualties.

Truck drivers volunteered for multiple runs despite knowing that each trip was essentially a suicide mission.

They went because they knew old blood and guts was counting on them and you didn’t let George Smith patent down.

On the morning of December 26th, 1944, General George Smith Patton entered Baston in person, riding in the lead vehicle of a relief column.

His arrival was pure theater, but it was theater that served a vital purpose.

The exhausted defenders of the 101st Airborne Division, men who had been surrounded and under constant attack for 10 days, saw the most famous general in the United States Army standing among them.

Old Blood and Guts personally shook hands with General Anthony Clement McAuliffe and told him, “You held them, Tony.

You did what needed to be done.

Now we’re going to finish them.

” The soldiers who witnessed this meeting would tell the story for the rest of their lives.

Here was George Smith Patton, who could have stayed safely at headquarters like every other army commander.

Instead, standing in a town that was still under artillery fire, congratulating the men who had held out against impossible odds.

It was leadership by example on a grand scale and it had precisely the effect Patton intended.

Word spread through the ranks like wildfire.

Old blood and guts is here.

Patton came himself.

The third army has arrived in force.

But George Smith Patton’s visit to Baston wasn’t purely symbolic.

He spent hours studying the tactical situation, examining maps, interrogating officers about German dispositions and capabilities.

While he was there, German artillery began shelling the town.

Staff officers urged Patton to take cover.

He ignored them, continuing his tactical conference as shells exploded in nearby streets.

When a particularly close explosion showered the group with debris, Patton simply brushed dust off his uniform and said, “They’ll have to do better than that to scare old blood and guts.

” The tactical situation remained critical despite the relief.

The Germans had committed substantial reserves to cutting off the Baston corridor and destroying the Third Army units that had penetrated their lines.

What had begun as a German offensive was now transforming into a massive battle of attrition in the frozen Ardens.

German commanders recognized that if they couldn’t destroy the forces at Baston, their entire offensive would collapse.

Adolf Hitler, furious at the failure to capture the town, ordered his generals to take Baston regardless of cost.

Fresh German divisions were diverted from other sectors and thrown into the battle.

General George Smith Patton anticipated this response and was ready for it.

Having broken through to Baston, he immediately began planning not just to hold the corridor, but to expand it, widen it, and then use Baston as a base to counterattack and destroy the German forces in the southern Arden.

While other commanders would have been satisfied with achieving the relief, Old Blood and Guts was already thinking three moves ahead.

Defense was not in his vocabulary.

Every position captured was a springboard for the next attack.

Gentlemen, Patton told his division commanders at a meeting on the evening of December 26th.

We have accomplished what the Germans said was impossible.

We turned an army, marched through a blizzard, broke through their lines, and relieved Baston.

Now, we’re going to do something they’ll find even more impossible.

We’re going to attack north and east, cut off their salient, and destroy every German division in this bulge.

Old Blood and Guts didn’t come here to defend.

We came here to kill Germans.

The attacks began on December 27th, 1944.

While the weather remained terrible, and casualties mounted.

The Third Army maintained relentless pressure.

The Fourth Armored Division, bloodied but unbowed, continued pushing north.

The 26th Infantry Division widened the corridor and protected the supply line.

The 80th Infantry Division attacked German positions to the east.

Every day brought new objectives, new attacks, new advances measured in hundreds of yards or a few miles at most.

But the cumulative effect was devastating to German plans.

The German high command began to realize that their offensive had failed.

They had achieved initial surprise and had driven a deep salient into Allied lines, but they had not broken through to the Muse River.

They had not captured their objectives.

They had not forced the Allies to negotiate.

And now George Smith Patton’s counterattack was threatening to turn their offensive into a catastrophic defeat.

German units that had been attacking westward were now fighting desperately to defend their positions against attacks from the south.

Field Marshal Gervan Runstead, the overall German commander in the West, sent increasingly pessimistic reports to Berlin.

His staff officers calculated that if the Third Army continued its advance at the current rate, major German formations would be cut off and destroyed.

Von Runet requested permission to withdraw to more defensible positions.

Adolf Hitler refused.

The battle continued with increasing fury as the calendar turned to 1945.

Throughout these desperate days, General George Smith Patton was everywhere his army fought.

He visited frontline units daily, often under fire.

He personally directed traffic during critical supply operations.

He stood in observation posts watching attacks develop and immediately ordered reinforcements or changes in tactics based on what he saw.

His staff officers aged years and weeks trying to keep up with old blood and guts relentless pace.

Colonel Halley Maddox later wrote in his official report.

General Patton required an average of four hours of sleep per night during the Baston operation.

He expected his staff to maintain the same schedule.

Anyone who couldn’t keep up was replaced.

This was not cruelty, but necessity.

Wars are not won by well-rested officers, but by commanders who refuse to stop pushing until victory is achieved.

The United States soldiers fighting under George Smith Patton’s command developed an almost mythical faith in their commander during these weeks.

They knew that Old Blood and Guts was asking everything of them, driving them beyond normal human endurance.

But they also knew he was up there with them, that he was sharing the same risks, eating the same rations, sleeping in the same frozen conditions.

When a soldier from the fourth armored division was asked by a reporter how he felt about General Patton’s aggressive tactics that led to heavy casualties, the soldier replied, “I’d follow old blood and guts into hell itself if he asked.

” Because I know he’d be leading the way.

By early January 1945, the tactical situation had completely reversed.

The German offensive was clearly defeated.

The salient they had driven into Allied lines was being compressed from all sides.

George Smith Patton’s third army was advancing from the south.

General Courtney Hicks Haj’s first army was attacking from the north.

The Germans were being pushed back toward their starting positions with catastrophic losses in men and equipment.

The Battle of the Bulge, which had begun with such high German hopes, was ending in comprehensive Allied victory.

But the cost had been staggering.

The Arden’s campaign would eventually result in over 90,000 United States casualties, including more than 19,000 killed in action.

The German losses were even worse.

Over a 100,000 casualties and hundreds of irreplaceable tanks and aircraft for both sides.

The battle represented one of the largest and bloodiest engagements of the entire war in Western Europe.

On January 16th, 1945, exactly one month after the German offensive began, United States forces from the North and South met and sealed off the bulge completely.

General George Smith Patton and General Courtney Hicks Hodgeges shook hands at the meeting point, symbolizing the Allied victory.

Photographers captured the moment, but those who were there later recalled that Patton seemed almost disappointed.

He had wanted to push farther to trap more Germans to turn the defensive victory into a war-winning offensive thrust into Germany itself.

We should be in Berlin in 6 weeks.

George Smith Patton told anyone who would listen.

We have the Germans reeling.

Old blood and guts wants to keep attacking, not stop and consolidate.

Every day we delay is a day they use to rebuild their defenses.

But the Supreme Allied Command had different priorities.

The massive casualties and equipment losses from the Arden’s campaign meant that the Allies needed time to rebuild their strength before launching the final push into Germany.

Supplies needed to be accumulated.

Fresh divisions needed to be brought forward.

The political and military leadership wanted to ensure that when they did cross into Germany, they would have overwhelming force.

It was cautious, professional, sensible military planning.

General George Smith Patton hated every moment of it.

Old blood and guts believed that in war, momentum was everything.

You hit the enemy and kept hitting him until he broke.

You didn’t give him time to recover, time to reorganize, time to build new defenses.

Every instinct in Patton’s aggressive nature screamed to keep attacking, but he was a soldier, and soldiers follow orders even when they disagree with them.

The relief of Baston and the subsequent defeat of the German offensive became the most celebrated achievement of General George Smith Patton’s career.

Military historians analyzing the campaign calculated that Patton’s Third Army had moved over 130,000 men, more than 100 m in less than a week in the worst winter weather in decades, while maintaining combat effectiveness sufficient to attack and defeat veteran German units.

The speed of the movement, the complexity of the logistics, and the tactical execution of the subsequent battle were studied at militarymies around the world as examples of operational art at its highest level.

But for George Smith, Patton himself, Baston was simply proof of what he had always believed, that audacity, speed, and aggressive leadership could overcome any obstacle.

He had spent his entire career preparing for moments like this, studying the great commanders of history, developing his tactical principles and training his staff to execute complex operations under impossible conditions.

When the moment came, old blood and guts was ready.

German military officers captured during and after the Battle of the Bulge were asked repeatedly about their assessment of Allied commanders.

Their answers were remarkably consistent.

They respected Eisenhower as an organizer.

They considered Bradley competent but predictable.

They dismissed Montgomery as overly cautious.

But when they spoke about General George Smith Patton, their tone changed.

They used words like aggressive, unpredictable, dangerous, and repeatedly brilliant.

One captured German colonel, when asked what single factor most disrupted the German offensive, replied simply, “Patton.

We planned for everything except Patton.

” The German high command’s assessment of the relief of Bastoni being operationally impossible had been based on sound military principles and historical precedent.

Large armies simply did not move that quickly in winter.

The logistics were too complex, the roads too poor, the weather too brutal.

Every staff college in the world would have calculated that what Patton did required a minimum of 2 weeks and probably three.

The Germans had based their entire operational timeline on this assumption.

They had forgotten that rules and precedents meant nothing to old blood and guts.

George Smith Patton didn’t accept limitations.

He didn’t recognize the word impossible.

When told something couldn’t be done, he took it as a personal challenge.

This mindset, combined with meticulous planning and ruthless execution, allowed him to achieve what others considered impossible.

Lieutenant General Fritz Berline, a veteran German commander who had fought against Patton in both North Africa and France, was captured in the final weeks of the war.

During his interrogation, he was asked about Allied generals.

His assessment of George Smith Patton was telling.

Patton was the most dangerous man they had.

Not because he had more tanks or more men, but because he thought differently.

He was willing to take risks that other Allied commanders would never consider.

When you fought the Americans elsewhere, you could predict their actions, prepare your defenses, and fight effectively.

When you fought Patton’s third army, you never knew where or when he would attack.

He kept you off balance constantly.

That is the mark of a truly great commander.

The soldiers who served under General George Smith Patton during the Bastoni operation carried those memories for the rest of their lives.

Veterans organizations devoted to the Third Army remained active for decades after the war.

Holding reunions where elderly men would share stories of old blood and guts.

The common theme in these stories was not just Patton’s military genius, but his personal leadership.

These men had seen their commander at the front under fire, sharing their dangers.

They had heard his profane, aggressive speeches that promised violence against the enemy and glory for the Third Army.

They had watched him personally direct traffic, inspect positions, and demand the impossible from everyone, including himself.

I served under other generals during the war, one veteran recalled at a reunion in 1983.

But I only ever loved one of them.

General George Smith Patton asked more of us than any human should ask of another.

He drove us harder than we thought we could be driven.

But he was right there with us and we would have followed old blood and guts anywhere.

The immediate aftermath of the Baston relief revealed both the genius of General George Smith Patton’s operation and the terrible cost of the Battle of the Bulge.

In the weeks following the breakthrough, as Allied forces compressed and eliminated the German salient, the full scale of the achievement became apparent.

The Third Army had not merely relieved a besieged garrison.

It had conducted one of the most remarkable military maneuvers in modern history and in doing so had dealt a devastating blow to German military power.

General Dwight David Eisenhower, who had authorized Patton’s audacious plan despite the skepticism of other commanders, visited the Third Army headquarters in early January 1945.

His meeting with George Smith Patton was warm and congratulatory, but those present noted an interesting dynamic.

Eisenhower praised the relief of Baston, but also gently reminded Patton of the need to coordinate with other Allied forces and not pursue independent operations that might create vulnerabilities.

Patton listened politely and then said something that everyone remembered.

Ike, you asked me to do the impossible and old blood and guts did it.

Now I’m asking you to let me keep doing the impossible all the way to Berlin.

Eisenhower smiled but didn’t commit to Patton’s aggressive proposals for immediate deep thrusts into Germany.

The cautious approach of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force frustrated George Smith Patton endlessly, but he remained a loyal subordinate even while privately fuming about missed opportunities.

Winston Churchill, the British Prime Minister, made a statement in the House of Commons that acknowledged the relief of Bastin as a turning point in the battle.

While Churchill carefully praised the efforts of all Allied forces, he made specific mention of the remarkable speed and effectiveness of General Patton’s third army in relieving the besieged garrison.

For Churchill, who had sometimes been skeptical of United States military effectiveness early in the war, this was high praise indeed.

The prime minister recognized that George Smith Patton had accomplished something that even British military experts had considered impossible.

The British military establishment, which had often viewed Patton as reckless and undisiplined, was forced to reassess their opinion.

Field Marshall Bernard Law Montgomery, who had publicly doubted the feasibility of Patton’s plan, said nothing publicly about the success.

Privately, however, intercepted communications and diary entries from British officers revealed a grudging admiration.

One British general wrote in his diary, “Patton is impossible to work with and breaks every rule in the book, but one must admit the man gets results.

” His relief of Bastoni was a remarkable achievement that I would not have believed possible if I hadn’t witnessed it.

The German assessment was even more illuminating.

After the war, when Allied intelligence officers compiled comprehensive reports on German decision-making during the Battle of the Bulge, captured documents revealed that the German high command had been stunned by the speed of Patton’s response.

Field Marshal Ger von Runet staff had produced detailed calculations showing that Allied relief forces could not reach Baston before late December at the earliest and more likely not until early January 1945.

These calculations were based on standard military planning factors and historical precedents.

They were professionally prepared and entirely reasonable.

They were also completely wrong because they failed to account for old blood and guts.

German intelligence reports captured after the war showed that German commanders had specifically identified General George Smith Patton as the most dangerous Allied general on the Western Front.

One assessment prepared in autumn of 1944 before the Ardan’s offensive began stated, “Patton is the only Allied commander who consistently demonstrates genuine offensive spirit.

His third army must be carefully monitored as he is capable of rapid aggressive action that could disrupt operational plans.

However, current intelligence places third army in the SAR region well south of the planned defensive area.

By the time Patent can redeploy, the operation will have achieved its initial objectives.

This assessment was accurate in every detail except one.

It underestimated how quickly George Smith Patton could move.

The German staff officers who prepared this analysis were experienced professionals who understood military logistics and movement rates.

They simply couldn’t conceive of an army commander who would ignore conventional wisdom and drive his forces beyond normal endurance to achieve strategic surprise.

They planned for competent opponents and got old blood and guts instead.

After the war ended, General Hasso van Montuful, who commanded the fifth Panzer Army during the Battle of the Bulge, was interviewed extensively by United States military historians.

His assessment of the Baston operation was remarkably candid.

When we learned that Patton had turned his entire army and was attacking from the south in less than a week, I knew our offensive had failed.

Not because we couldn’t defeat his attack, we had strong forces in position, but because it demonstrated that Allied command was more flexible and aggressive than we had calculated.

If Patton could do the impossible at Baston, what else might the Allies do that we hadn’t planned for? That psychological impact was as important as the tactical situation.

The United States press, which had been reporting the dire situation in the Ardens with increasing alarm, seized on the relief of Baston as a redemption story.

Headlines across the country proclaimed Patton saves Baston and old blood and guts does it again.

The American public, which had been shocked by the news of the German offensive and the initial Allied reverses, found reassurance in the story of George Smith Patton’s aggressive counterattack.

Here was an American general who embodied the national spirit.

Bold, confident, and ultimately victorious.

Magazine articles and newsre footage brought the story of the Baston relief to millions of Americans.

General George Smith Patton, who had always understood the importance of public relations and personal image, gave carefully crafted interviews that emphasized the courage of the common soldier, while also making clear that aggressive leadership and tactical boldness had made the victory possible.

Old Blood and Guts is proud of every man in the Third Army, he told one reporter.

They did what I asked because they trusted me to lead them to victory.

That trust is the most precious thing a commander can possess.

The soldiers of the Third Army, reading these accounts in military newspapers and letters from home, felt a fierce pride in their accomplishments.

They had done something extraordinary, and the world knew it.

Veterans of the Bastoni operation wore their Third Army patches with special pride for the rest of their lives.

They were old blood and gutsmen, and they had proven what audacity and courage could accomplish.

The long-term strategic impact of the Bastoni relief extended far beyond the immediate tactical situation.

By defeating the German offensive in the Arden, the Allies had destroyed Germany’s last operational reserve in the west.

The divisions that Hitler committed to the Battle of the Bulge were his best remaining forces, and they had been shattered against Allied defenses and counterattacks.

When the final Allied offensive into Germany began in the spring of 1945, the Germans lacked the mobile reserves necessary to mount effective counterattacks.

They had gambled everything on the Arden’s offensive and lost.

General George Smith Patton’s role in this strategic victory was central by relieving Baston and then driving the Germans back with relentless attacks.

He had turned what could have been a catastrophic Allied defeat into a victory that shortened the war.

Military historians continue to debate how much longer the war might have lasted if the German offensive had succeeded in splitting the Allied armies and capturing Antworp.

Estimates range from 6 months to a year of additional fighting.

The cost in lives, both military and civilian, would have been staggering.

The relief of Baston also fundamentally changed how Allied forces approached operations for the remainder of the war.

The success of Patton’s rapid redeployment demonstrated that with proper planning and aggressive leadership, large armies could move and fight with unprecedented speed and flexibility.

This lesson influenced Allied planning for the final campaigns in Germany and later shaped United States military doctrine for decades.

At the command and general staff college at Fort Levvenworth, Kansas, the Bastoni relief operation became a central case study in teaching operational art.

Officer students studied every aspect of the operation, the planning, the logistics, the movement control, the tactical execution.

The lesson was clear.

Audacity and aggressive leadership when combined with meticulous staff work and proper preparation could achieve results that conventional planning said were impossible.

Generations of United States Army officers learned to ask themselves, “What would old blood and guts do in this situation?” But perhaps the most profound impact was on military culture and the concept of leadership.

General George Smith Patton’s example of leading from the front, of sharing dangers with his troops, of demanding the impossible and then delivering it, became embedded in United States military tradition.

The post-war army, reflecting on the lessons of World War II, emphasized aggressive leadership and personal courage in ways that directly reflected Patton’s influence.

The soldiers who had served under George Smith Patton during the Baston operation told their children and grandchildren about old blood and guts.

These stories shared around dinner tables and at family gatherings for decades kept Patton’s legend alive in American culture.

He became a symbol of American military excellence.

a commander who embodied courage, skill, and indomitable will.

German military professionals, many of whom went on to serve in the postwar West German military, continued to study the Baston relief as an example of operational excellence.

General Hans Spidel, who served in the German army during World War II and later became a senior commander in NATO, wrote in his memoirs, “Patton’s relief of Baston demonstrated that superior command can overcome material disadvantages and difficult conditions.

We Germans prided ourselves on operational flexibility and aggressive maneuver.

Patton beat us at our own game.

” The contrast between George Smith Patton’s aggressive style and the more cautious approach of other Allied commanders became a subject of endless debate among military historians.

Some argued that Patton’s methods were reckless and resulted in unnecessary casualties.

Others maintained that his aggressive spirit won battles and shortened the war, ultimately saving lives.

What no one could dispute was that when the situation demanded the impossible, old blood and guts delivered.

In the decades following World War II, as historians gained access to more documents and conducted more interviews, the full scope of what George Smith Patton accomplished at Baston became even more impressive.

The logistical planning alone was staggering.

Staff officers had to coordinate the movement of over 130,000 men and 25,000 vehicles over roads that were barely passable.

They had to redirect hundreds of thousands of gallons of fuel, millions of rounds of ammunition, and thousands of tons of supplies.

They had to maintain communication security while coordinating with adjacent units.

They had to do all of this in less than 72 hours in the middle of winter while maintaining combat operations in multiple sectors.

That this operation succeeded was a testament not just to George Smith Patton’s leadership, but to the professionalism and dedication of the entire Third Army staff.

Colonel Halley Maddox, Patton’s operations officer, later received well-deserved recognition for his role in planning and executing the movement.

But Maddox himself always insisted that the key factor was Patton’s leadership.

The general gave us an impossible mission, Maddox said in a postwar interview.

But he also gave us the authority and resources to accomplish it.

Old blood and guts never asked us to do anything he wasn’t willing to do himself.

That kind of leadership inspires people to achieve things they didn’t know they were capable of.

The relief of Bastoni also demonstrated the importance of prior planning and preparation.

George Smith Patton’s insistence on developing contingency plans for rapid redeployment, which had seemed almost paranoid to some staff officers, proved to be the key to success.

When the crisis came, Patton didn’t need to start planning from scratch.

He already had detailed plans prepared for exactly this type of situation.

All that remained was to execute those plans with appropriate modifications for the specific circumstances.

This aspect of Patton’s command style, the combination of aggressive boldness with meticulous preparation, is often overlooked in popular accounts that focus on his colorful personality and dramatic battlefield leadership.

But professional military officers studying his campaigns understood that Old Blood and Guts’s success came from much more than just courage and aggression.

George Smith Patton was a deeply professional officer who studied military history extensively, who understood logistics and intelligence, who trained his staff to the highest standards, and who prepared for every contingency.

When he took risks, they were calculated risks based on careful analysis, not reckless gambles.

The personal testimonials from soldiers who served under General George Smith Patton during the Bastoni operation, provide the most moving evidence of his leadership impact.

Decades after the war, these veterans still spoke with emotion about old blood and guts.

They remembered specific moments when Patton visited their units, encouraged them, and demanded their best efforts.

They remembered his distinctive appearance with the pearl-handled pistols and the highly polished helmet.

They remembered his profane speeches that somehow made them feel 10 ft tall and ready to take on the world.

One veteran speaking at a Third Army reunion in 1992, nearly 50 years after Baston, said, “I’m an old man now, and I’ve had a good life.

But when I think about the moment I’m most proud of, it’s not my career or my family, though I love them dearly.

It’s those days in December 1944 when I marched through a blizzard because General George Smith Patton said we were needed and old blood and guts had never let us down.

We did the impossible because he believed we could.

That’s leadership.

The relief of Baston crystallized everything that made General George Smith Patton a legendary figure in military history.

It demonstrated his tactical genius, his aggressive spirit, his personal courage, and his ability to inspire ordinary soldiers to achieve extraordinary results.

But more than that, it represented a philosophy of warfare that George Smith Patton had developed over a lifetime of study and combat.

that speed, audacity, and relentless pressure could overcome any obstacle and defeat any enemy.

Old Blood and Guts believed that war was not a chess game to be played cautiously, but a storm to be unleashed with maximum violence and determination.

He believed that soldiers fought best when led by commanders who shared their dangers and their hardships.

He believed that aggressive action, even with imperfect information and incomplete preparation, was better than cautious planning that gave the enemy time to recover.

Most importantly, he believed that the word impossible was simply an excuse used by people who lacked the courage to attempt difficult things.

These beliefs were vindicated at Baston.

When every professional military assessment said that relief was impossible in the available time frame, George Smith Patton proved them wrong.

When German commanders calculated that they had weeks before facing serious counterattacks, old blood and guts hit them in days.

When conventional wisdom said that winter weather made large-scale operations impossible, the Third Army moved an entire core over a 100 miles and attacked with devastating effect.

Modern military historians with access to documents from both sides and decades of perspective have consistently rated the Baston relief as one of the most impressive operational achievements of World War II.

Dr.

Martin Blummenson, one of the foremost experts on George Smith Patton and author of the definitive multi-olume biography, wrote, “The relief of Baston demonstrated operational art at the highest level.

Patton combined strategic vision, operational planning, tactical execution, and personal leadership in a way that few commanders in history have matched.

That he accomplished this under the worst possible conditions makes the achievement even more remarkable.

” General John Michael Scoffield, who served as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the 1980s, speaking at a military history conference, said, “Every officer in the United States military studies the Bastoni operation at some point in their career.

The lessons are timeless.

Speed matters.

Aggressive leadership matters.

Proper preparation enables audacious execution.

These principles, demonstrated by General George Smith Patton in December 1944, remain as valid today as they were then.

Old blood and guts set a standard that we still aspire to.

The United States Army’s command and general staff college includes the Bastoni relief in its advanced operations course where fieldgrade officers study the planning and execution in detail.

Students are walked through the decision-making process, the logistical challenges, the tactical complications, and the leadership requirements.

The consistent conclusion reached by these students after days of detailed analysis is that what Patton accomplished should have been impossible and yet he did it.

The follow-on question that instructors pose is how can you develop the capability to do the impossible when your country needs it.

This question cuts to the heart of George Smith Patton’s legacy.

Old Blood and Guts didn’t achieve the impossible through luck or overwhelming resources.

He did it through a combination of factors that any military officer can study and emulate.

Thorough preparation, aggressive execution, personal leadership, and an absolute refusal to accept limitations.

These are teachable principles, and the United States military has been teaching them for nearly 80 years since Baston.

The cultural impact of the Baston story extended far beyond military circles.

The 1970 film Patton, starring George C.

Scott in an Academy Award-winning performance brought General George Smith Patton story to millions of people around the world.

The film’s portrayal of the Bastoni operation, while compressed and dramatized for theatrical purposes, captured the essential truth that old blood and guts accomplished something everyone said was impossible through sheer force of will and brilliant military leadership.

Younger generations who never experienced World War II learned about George Smith Patton through this film and subsequent documentaries and books.

His famous speeches, his aggressive tactics, his controversial personality, and his undeniable military genius became part of American cultural mythology.

When people think of great American military leaders, General George Smith Patton is invariably near the top of the list, and the relief of Baston is often cited as his defining achievement.

What makes the Baston story so enduringly powerful is that it embodies fundamental human themes that transcend military history.

It’s a story about refusing to accept defeat when everyone else sees only hopelessness.

It’s about leadership that inspires ordinary people to achieve extraordinary things.

It’s about preparation meeting opportunity.

It’s about a man who spent his entire life training for a moment of supreme crisis and then rose to meet that challenge perfectly.

These are themes that resonate across generations and cultures.

The comparison between George Smith Patton and other World War II commanders inevitably arises when discussing his legacy.

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery was methodical and careful, achieving victories through overwhelming preparation and firepower.

General Omar Nelson Bradley was solid and dependable.

A commander who could be trusted to execute plans competently.

General Dwight David Eisenhower was a brilliant coalition manager and strategic planner who held the Allied command structure together despite enormous political pressures.

But when the situation required rapid aggressive action against overwhelming odds, there was only one commander the Allies could turn to, General George Smith Patton.

Old blood and guts was the hammer you used when you needed something broken quickly and completely.

He was the general you called when the mission was impossible and you needed someone who didn’t know the meaning of that word.

The relief of Baston proved this definitively.

German military professionals in their postwar assessments and memoirs consistently identified George Smith Patton as the Allied commander they feared most.

General Gunther Blumenrit who served as chief of staff to Field Marshall Gird von Runet wrote in his post-war memoirs, “Patton was our most dangerous opponent.

Montgomery we could predict and prepare for.

Bradley we could match with competent defense.

But Patton was different.

He attacked where we didn’t expect, moved faster than we thought possible, and took risks that other Allied commanders would never consider.

Fighting the Third Army required constant vigilance and maximum effort because old blood and guts never gave us a moment to rest or reorganize.

This German perspective validates what United States military historians have long argued that General George Smith Patton’s aggressive style and tactical brilliance made him uniquely effective in combat operations.

While other commanders might have been better politicians or coalition managers when it came to fighting and winning battles, Old Blood and Guts was in a class by himself.

The soldiers of the 101st Airborne Division, who survived the siege of Bastoni, maintained a special reverence for George Smith Patton for the rest of their lives.

They had been hours, or at most days, from annihilation when old blood and guts broke through.

Every man who walked out of Baston alive knew he owed his life to Patton’s aggressive leadership and the courage of the Third Army soldiers who had marched through a blizzard to save them.

At reunions of airborne veterans, it was common to hear toasts offered to Old Blood and Guts Patton, the man who saved Baston.

The tactical and operational lessons from the Baston relief, continue to influence modern military planning.

The concept of rapid force deployment, now formalized in United States military doctrine as deployment readiness, traces its lineage directly to what Patton demonstrated in December 1944.

The idea that large forces can be moved quickly to respond to unexpected crisis is now a cornerstone of American military planning.

But it was considered nearly impossible before George Smith Patton proved otherwise.

The emphasis on aggressive leadership and personal courage in United States military culture also reflects Patton’s influence.

The modern United States Army teaches its officers that leadership is not about staying safe in headquarters, but about sharing dangers with subordinates and leading by example.

This philosophy embodied so perfectly by old blood and guts throughout his career has become institutionalized in American military training and doctrine.

The question often posed by historians is whether anyone else could have accomplished what George Smith Patton did at Baston.

Could another commander have turned an army in 72 hours and attacked successfully? The consensus among military professionals is that while the physical movement might have been theoretically possible for other commanders, the combination of speed, surprise, and aggressive execution was uniquely Patton’s achievement.

Another general might have taken a week or 10 days to prepare the operation properly.

A more cautious commander might have delayed the attack to ensure better weather and air support.

A less aggressive leader might have been satisfied with simply opening a corridor to Baston rather than immediately exploiting the success with further attacks.

But General George Smith Patton did none of these things.

Old blood and guts moved as fast as humanly possible, attacked in terrible weather without waiting for perfect conditions, and then immediately exploited his success by continuing offensive operations.

This combination of speed, aggression, and relentless pressure was the signature of Patton’s command style, and it’s what made him the most successful combat commander the United States Army produced in World War II.

The broader strategic significance of the Baston Relief extended well beyond the immediate tactical victory.

By defeating the German Arden offensive, the Allies maintained the initiative on the Western Front and set the stage for the final campaigns that would end the war in Europe.

Had Baston fallen and the German offensive succeeded in splitting the Allied armies, the war might have dragged on well into 1946 with tens of thousands of additional casualties and incalculable additional destruction across Europe.

In this context, General George Smith Patton’s achievement at Bastoni quite literally changed the course of history.

The town of Baston itself has never forgotten the relief.

Every year on the anniversary of the breakthrough on December 26th, the Belgian community holds ceremonies honoring the soldiers who fought there.

A massive monument stands outside the town dedicated to the memory of the United States forces who defended Baston and the Third Army forces who relieved it.

Streets in the town are named after General George Smith Patton and other American commanders.

Museums preserve artifacts and tell the story of the siege and relief to new generations.

The people of Baston understand that their town survived because old blood and guts refused to accept that relief was impossible.

As we reflect on the relief of Baston more than 80 years after it occurred, several enduring truths emerge.

First, that aggressive inspired leadership can overcome seemingly impossible obstacles.

Second, that proper preparation creates the capacity for audacious execution.

Third, that speed and surprise can compensate for disadvantages in numbers or position.

Fourth, that soldiers will accomplish extraordinary things when led by commanders they trust and respect.

And finally, that the word impossible is meaningless to those with the courage to attempt great things.

These are the lessons of General George Smith Patton’s greatest achievement.

These are the reasons why the relief of Baston remains one of the most studied military operations in history.

And these are why when military professionals around the world discuss great military leadership, the name of old blood and guts inevitably arises.

The legend of General George Smith Patton extends far beyond any single battle or campaign.

His entire career from his youth spent studying military history through his Olympic pentathlon competition in 1912, his service in World War I, his development of armored warfare doctrine between the wars, and his brilliant campaigns across North Africa, Sicily, France, and Germany.

Represents the life of a man completely dedicated to the profession of arms.

But if one moment had to be chosen to represent George Smith Patton at his absolute best, it would be the 72 hours between December 19th and December 22nd, 1944.

when he turned an entire army and prepared to accomplish what every expert said was impossible.

That he then delivered on that promise, breaking through to Baston on Christmas Day and then continuing to attack and destroy German forces for weeks afterward, confirmed what his admirers had always believed and his critics had to acknowledge.

General George Smith Patton was a military genius, a combat leader without equal in his generation, and a commander who embodied everything that is best about the warrior spirit.

And that’s why they called him Old Blood and Guts.

If this story of General George Smith, Patton’s greatest military achievement has moved you, if you’ve been inspired by how Old Blood and Guts accomplished the impossible at Baston, then I need you to do something.

Hit that subscribe button right now.

We’re bringing you more untold stories from the life of General George Smith.

Patent, the battles, the controversies, the brilliant tactics, and the leadership lessons that made him history’s most fearsome combat commander.