May 8th, 1945.

Victory in Europe Day.

Across London, Paris, and New York, church bells rang and flags waved in the streets.

But thousands of miles away in the quiet farmland of Iowa, Kansas, and Texas, the news arrived in a different form.

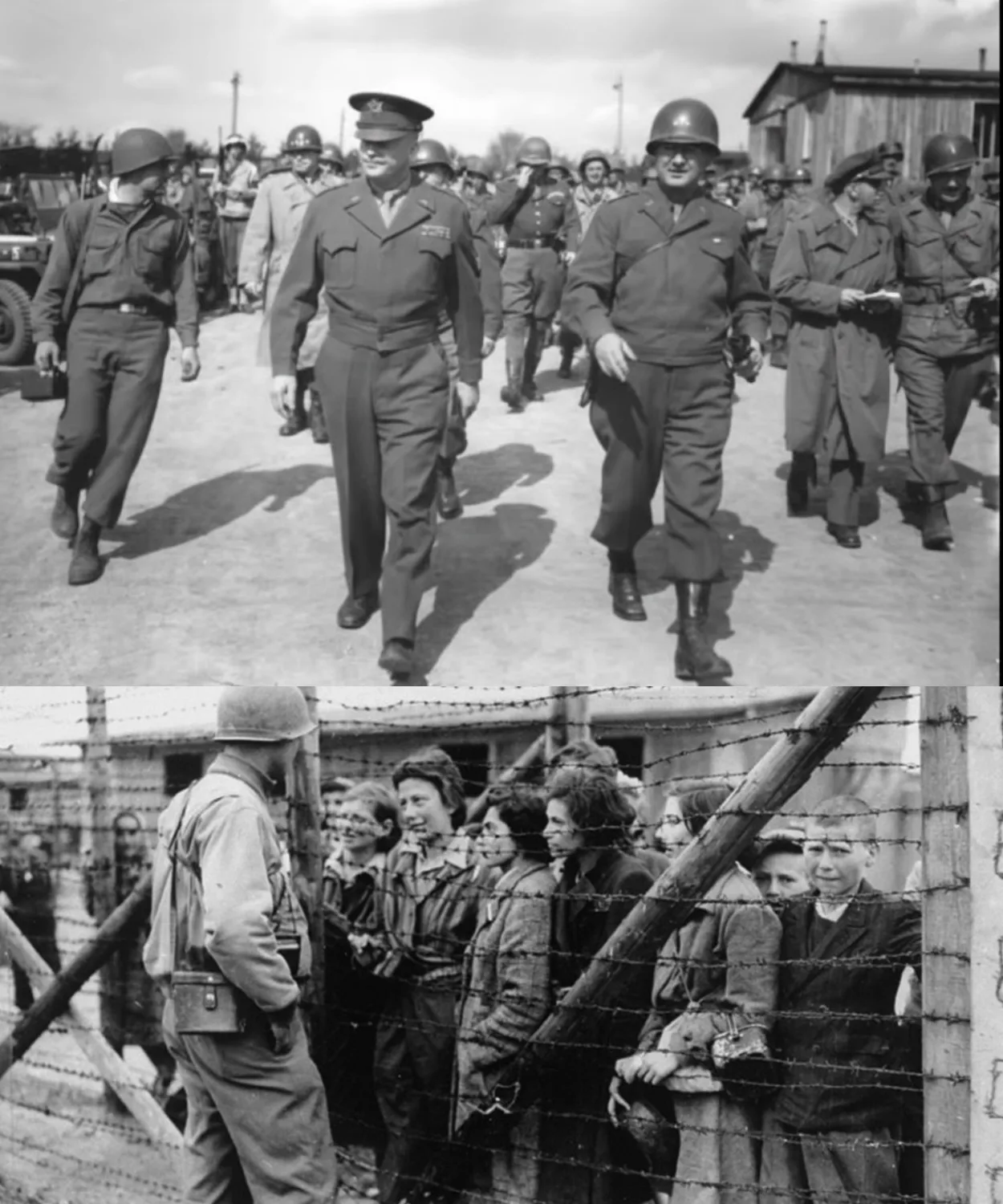

Inside camps surrounded by barbed wire, the war’s end was not marked with champagne or parades, but with a short announcement from the mouths of American officers.

Standing in front of assembled prisoners, men and women alike, they told them, “You can go home.” The words should have sounded like salvation, the long- awaited promise of release.

Yet in that instant, the silence that followed carried something stranger than celebration.

German women, many in their 20s, some older, looked at each other with downcast eyes.

A few shook their heads, whispering softly in their mother tongue, nin.

They had been brought across the ocean under suspicion and fear.

Some were auxiliaries in the Luwaffa Communications Corps, others nurses who had followed the Werem, and a few simply swept into captivity because they worked too close to the wrong unit.

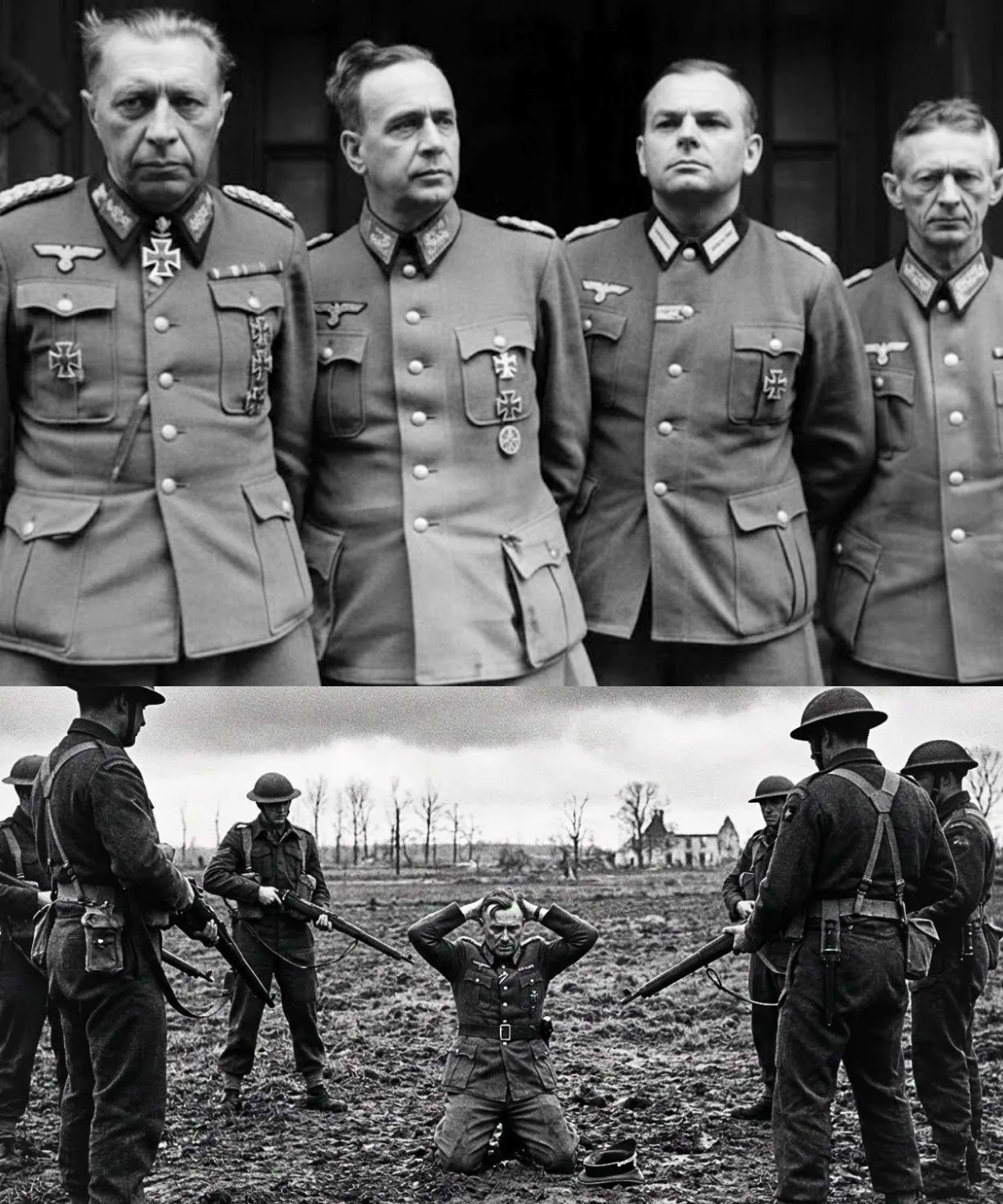

They were women who had once believed they would be treated with cruelty if captured by the enemy.

Nazi propaganda had warned of Americans as brutes, destroyers, men without mercy.

The voyage across the Atlantic in gray painted troop ships had been filled with dread.

Yet the months that followed overturned every expectation.

The camps in the American Midwest were hardly palaces, but they were orderly, clean, and most shocking of all, generous with food.

One young prisoner, not much older than 22, had scribbled into a battered notebook.

They feed us peanut butter, sticky, strange, but rich.

I cannot stop eating it.

Her handwriting, thin and jagged, conveyed astonishment rather than gratitude, as though even delight was a kind of betrayal of the world she had left behind.

Another woman, once a typist in a Luwaffa office, told a Red Cross interviewer that she had been given new shoes upon arrival.

She had not owned a new pair since 1941.

These were small comforts, but in wartime Europe, where families boiled nettles for soup and shoes were patched until nothing remained.

They were luxuries beyond imagining.

When the officers delivered their announcement on that spring morning, many expected an eruption of joy.

Instead, the reaction unsettled them.

A captain in Texas later recalled, “I thought they would run to the gate.” Some of them cried, but it wasn’t happiness.

It was something heavier.

For the women, going home meant stepping back into a world that barely existed.

Letters smuggled through the sensors told of bombed out streets, vanished relatives, and towns divided into occupation zones.

One note read aloud by a trembling 26-year-old in the barracks spoke of her mother starving in Hamburg and her brother missing in Russia.

Going home no longer meant reunion.

It meant rubble, hunger, and fear.

The conflict between the words, “You can go.” And the quiet refusal that followed revealed a truth both sides struggled to comprehend.

These women, captives in a foreign land, had begun to see captivity itself as safety.

Behind the wire, they were watched, yes, but they were also sheltered, their bellies filled, their dignity sometimes restored in ways they had not expected.

They were even allowed to work.

In Kansas, farm families watched with suspicion as lines of German women marched into the fields to harvest sugar beats.

But suspicion melted when the women laughed at the endless rows, joking in broken English that America has more corn than soldiers.

Even in chains, humor had returned to them.

The American guards were not blind to the transformation.

A sergeant in Iowa admitted later, “They looked so young.

You forgot they were the enemy.

” At night, music drifted from the barracks.

Accordians carried from Europe, filling the still air above the prairie.

For a moment the sound was neither German nor American.

It was human.

And in that humanity, something complicated took root.

Still, the orders were clear.

The Geneva Convention required repatriation.

America had no intention of keeping its prisoners, least of all women, any longer than necessary.

But what the officers could not predict was the resistance to freedom itself.

One lieutenant in Texas, flustered by the sight of prisoners weeping at his announcement, repeated the words as though they might change meaning if spoken again.

“You can go home,” he insisted.

Yet a woman at the front of the group shook her head in halting English, she said.

“Home? No home left.

” It was a sentence that cut through every illusion.

America could open the gates, but what lay beyond them was not a homeland waiting with open arms.

It was ruins.

In the Soviet zone, rumors of mass assaults spread through the camps like wildfire.

Even in the western zones, food shortages were chronic.

Cities were blackened skeletons, and millions wandered as displaced persons.

To leave the camp in Iowa for Bremen or Dresdon was not liberation.

It was exile into nothingness.

The strangeness of the moment is hard to overstate.

Officers stood bewildered, their uniforms dusty from long service, their orders clear, while before them stood women who should have rushed to board the trains east, begging instead to remain behind barbed wire in the land of their conquerors.

The irony was sharp enough to sting.

America, which had once been painted as a monster in Nazi propaganda, had become, for these women the only refuge they trusted.

A young guard, no more than 19, later described it in a letter home.

I never thought the enemy would ask me to keep them prisoners.

But some of the girls cry when they think of going back.

They are safer here than free out there.

He admitted the sight haunted him.

War had turned the world upside down, and here was its proof.

Captivity desired, freedom feared.

The scene played out in camp after camp across the American heartland.

Not all resisted.

Some were desperate to see what remained of family and home.

But enough begged to stay that the officers began to understand the depth of devastation in Europe.

Each petition, each quiet refusal was less about loyalty to Germany and more about terror of what Germany had become.

The women were not clinging to their captives.

They were clinging to the last place where life felt bearable.

When the announcement ended and the officers dismissed them, the women did not scatter with excitement.

They returned to their barracks slowly, subdued, carrying questions heavier than the packs they had once hauled across Europe.

That night the lights burned late.

Some wrote letters in neat script, asking relatives if there was still a roof to return to.

Others simply sat in silence, staring at the wooden walls as if trying to measure the distance between barbed wire and freedom.

And so the story began, not of liberation in the traditional sense, but of an unexpected conflict, the desire to remain in captivity, to trade a ruined homeland for the uneasy safety of a foreign prison.

The officers had spoken their line, “You can go home.” But for many of the women, the phrase carried no promise, only dread.

In the weeks that followed, petitions would be written, arguments made, tears shed.

The world expected prisoners to crave release, but the reality was stranger.

The gates stood open, and yet many chose to stay.

And what came next would astonish even the officers themselves.

The camps where the German women lived were never meant to be permanent homes.

Yet for many they became something closer to stability than anything waiting across the ocean.

Wooden barracks, neat and rows, stood against the endless horizons of the American Midwest.

The mornings began with the clang of a bell, the smell of boiled coffee drifting from the guards quarters and the shuffle of boots on gravel as prisoners filed into work details.

To outsiders, it looked like captivity.

To the women inside, it felt strangely like survival.

Daily life unfolded in rhythms that had little to do with war.

In Texas, women rose early to peel mountains of potatoes in camp kitchens, the smell of starch thick in the humid air.

In Iowa, they worked on farms under arms supervision, bending over fields of corn and sugar beats, their dresses clinging with sweat, the sun fierce on their back.

American families sometimes watched from a distance, weary eyes peering from porches, expecting defiance or sabotage.

What they saw instead was laughter carried on the wind.

Women joking in German, sometimes daring to mimic the English words they overheard.

A farmer once told a guard half ingest, “If they keep working like this, I’ll hire them after the war.” Small acts of kindness crept in despite official boundaries.

A guard in Kansas slipped an apple to a prisoner during a long day in the field.

She bit into it slowly, savoring the crisp sweetness, and later wrote in her diary.

It tasted of peace.

Another young woman, once a typist in Stoutgart, remembered the first time she entered an American grocery store under guard escort.

Rows of canned goods gleamed under electric light, soap stacked in neat towers, fabrics folded in rainbow colors.

I thought it was a dream, she confessed years later, to see so much of everything.

The abundance mocked the memories of her homeland, where Q’s wounded around rubble strewn streets for a few ounces of flour.

The contrast between expectation and reality grew sharper with each passing month.

The women had been warned by Nazi propaganda that American imprisonment meant brutality, hunger, perhaps even death.

Instead, they found themselves with three meals a day, sometimes as much as 3,200 calories, according to Red Cross reports.

It was more than most civilians in Germany ate in those final years of the war when rations had shriveled to near starvation.

Meat appeared on their plates, bread was soft and white, and for the first time in years, they washed their hair with real soap.

The irony was not lost on them.

One woman remarked to her Barack mates that she had been more nourished behind barbed wire than she ever had been in her own home.

The Americans, too, adjusted their perceptions.

At first, suspicion weighed heavy.

To many guards, a German uniform, even on a woman, carried the same stain as a weapon, but gradually distance gave way to recognition.

They saw the fatigue in the women’s faces, the longing when letters arrived from overseas, the way they clutched photographs of family worn soft at the edges.

A sergeant in Oklahoma remembered thinking, “They look no older than my sister.

How could I call them enemy?” The lines blurred, though never officially acknowledged.

Music became a bridge across the divide.

At night, the women gathered in their barracks, one with an accordion, another tapping rhythm on the wooden frame of a bed.

Songs filled the air, sometimes German folk tunes, sometimes hymns remembered from childhood.

Guards paused in their patrols to listen, the melancholy notes drifting into the prairie night.

For the women, it was a way of keeping their humanity intact, a way of reminding themselves that beyond the barbed wire, life still had a melody.

Not everything was easy.

Loneliness pressed hard, and tempers flared in close quarters.

Quarrels broke out over letters, over memories, over rumors of what awaited them back in Germany.

But even these moments deepened the paradox.

Within the camp’s fences, they argued like neighbors rather than prisoners.

They had, in some sense, formed a fragile community, bound together by shared uncertainty and an unexpected discovery of dignity.

A humor of survival threaded through their days.

They teased one another about their English accents, laughed at the endless meals of cornbread, and joked about how Americans seemed to put corn into everything.

One woman standing kneedeep in a field in Iowa threw her hands up and declared, “If the war does not kill me, Korn will.” The guard beside her laughed, unable to help himself.

It was a small moment, but it chipped away at the walls both sides had built, and yet beneath the laughter and the steady work, shadows lingered.

News filtered in from Europe, and each report darkened the barracks.

cities flattened by bombing, families lost in the east, and the slow, grinding hunger that devoured what little remained of the Reich.

The women compared those stories with the warm meals in front of them, and the comparisons carved out a new fear.

Freedom meant leaving behind the only place where they were safe and fed.

The conflict became more visible as the months passed.

Guards noticed tears during mail call.

Women clinging to letters as if to keep the paper from blowing away.

One recalled seeing a prisoner stand silently for an hour at the fence line, staring westward as though trying to memorize the outline of the American horizon.

It was not affection for the country that held her captive.

It was dread of the one that waited beyond.

The camps became places of contradiction.

Prisons that nourished, walls that protected rather than confined.

The women themselves became contradictions, too.

Soldiers without weapons, captives who feared release.

Officers struggled to make sense of it.

Why would anyone choose to remain behind wire rather than claim freedom? The answer grew clearer with each testimony because the world outside had collapsed.

In this paradox lay the heart of their story.

They were not rejecting home.

They were rejecting ruin.

They were not embracing America.

They were clinging to the last semblance of security.

And as the officers prepared for the inevitable process of repatriation, the pleas began to surface.

Some were whispered in broken English, others scribbled onto scraps of paper.

Please let us stay.

It was a strange plea for prisoners to make, one that unsettled the officers who heard it.

Captivity had become refuge, and freedom had become fear.

The irony was sharp, the kind that history seems almost too cruel to invent.

The barbed wire meant to divide had become their shield.

And soon, as orders for transport loomed closer, those shields would be stripped away.

The women knew it.

The guards suspected it, and what came next would test both sides in ways neither had expected.

The first trains bound for the east stood ready in the summer of 1946, their iron wheels glinting beneath the prairie sun.

For the American officers, the task seemed straightforward.

Repatriate the prisoners, as the Geneva Convention required, restore order by sending them back to the soil of their homeland.

But for the women who had lived a year or more behind the wire, the thought of stepping onto those trains filled them with d potent than captivity itself.

Letters from Europe had already painted the outlines of a nightmare.

Hamburg was a city of scorched bricks.

Dresdon still smoldered.

Cologne was described not as a city but as a lunar landscape of chimneys.

Even the western zones under British and American control staggered under shortages.

Families traded heirlooms for potatoes.

Children fainted in schools from hunger.

And a woman might walk 10 miles for a pound of flour.

The prisoners knew these stories not from propaganda, but from the ink of trembling hands folded into envelopes that reached them across the Atlantic.

One 24year-old Luwaffa auxiliary named Hanalor read aloud to her bunkmates the words of her mother in Hanover.

Your sister is gone.

Your father is missing.

I sleep in the cellar because the roof has holes.

If you return, I do not know where you will sleep.

The letter crumbled in her grasp, but the terror in her voice lingered long after the paper was folded away.

Another woman broke down when she learned her village had been consumed by the Soviet advance.

She whispered to a guard in halting English, “My home does not exist.” To the officers, going home was a matter of logistics.

To the women, it was a sentence to wander among ruins, begging for scraps.

One camp commonant later admitted that the pleas unsettled him more than any defiance.

It was easier to handle hatred than despair.

Some women attempted petitions, scrawling notes that begged for extension of captivity or work contracts within the United States.

Others tried more desperate appeals, volunteering as nurses in American hospitals or offering to clean barracks simply to remain within the perimeter.

A few even asked if they might marry their way into America, though regulations made such requests impossible at the time.

What made the fear sharper was the looming spectre of the Soviet zone.

Stories trickled into the camps of mass reprisals, of women dragged from sellers, of villages emptied in the night.

Even those destined for British or American sectors feared the journey east.

Four trains often deposited their passengers in temporary camps with little food and no certainty of where they would go next.

A young woman named Latte, once a secretary in Bremen, told a fellow prisoner that she would rather scrub floors in Texas for the rest of her life than risk a single night in the Soviet zone.

Her words echoed among the bunks like a vow, though all knew it was one she could not keep.

The irony struck many of the Americans who overheard these conversations.

They had been trained to view Germans as fanatical, loyal to Hitler until the bitter end.

Instead, they encountered women who feared their own country more than the barbed wire of their captives.

A 19-year-old guard described it in a letter home.

They are afraid of freedom.

Can you imagine? They cry when they think of going back.

They say there is nothing left there, nothing to eat, nothing to live for.

Some of them would rather be our prisoners forever.

Even small details of daily life reinforce the chasm between America and Germany.

A prisoner in Kansas marveled that she could wash with soap every week.

Her sister in Frankfurt wrote that she had not bathed in months, water being too scarce and soap non-existent.

In Oklahoma, women sang to the rhythm of accordion music.

In Berlin, survivors huddled in sellers listening to the groan of collapsing walls.

The comparisons haunted them.

Captivity, once feared, had become the only world where life held rhythm and nourishment.

And yet orders came down with bureaucratic precision.

Trains would depart on schedule.

Ships would ferry them across the Atlantic and the US Army would have discharged its responsibility.

In briefings, officers repeated the line that the women should be grateful for release.

Few considered what awaited them on the other side of the ocean.

The women themselves tried to imagine it, stepping off a ship into Bremer Havin, only to find strangers picking through rubble where their childhood homes once stood.

Would their mothers still be alive? Would their children, if any, even recognize them? These questions pressed so hard that many lay awake in the barracks, staring at the ceiling beams, listening to the sigh of their neighbors, who could not sleep either.

One night in Iowa, a storm lashed against the barracks, rain hammering the roof, wind rattling the shutters.

Inside, the women huddled together, their voices hushed.

They spoke not of homecomings, but of fears.

“We will be forgotten,” one said.

Another murmured, “we will go back as beggars.” A third whispered the darkest thought of all.

“Better to stay a prisoner than to be free in ruins.” The lightning cracked across the prairie, illuminating their pale faces, and for a moment they looked less like captives than exiles, waiting for judgment.

The Americans tried to reassure them.

A chaplain told the prisoners that rebuilding was possible, that Germany would rise again.

His words were sincere, but they carried no bread, no roof, no safety.

The women nodded politely, but afterward one confided to a friend.

It is easy to speak of rebuilding when your home is not ash.

The sentence carried the weariness of a generation watching their country vanish beneath their feet.

As departure neared, the women began to change.

They walked slower to roll call, lingered longer at the fences, stared longer at the American horizon they would soon leave behind.

Some guards, hardened by long service, found themselves moved by the sight.

One remembered a young woman tracing her finger along the barbed wire as if trying to memorize the feel of it, her last anchor, before being cast into uncertainty.

I thought prisons were supposed to hold people against their will, he wrote later.

But these prisoners held onto the prison.

The final days in camp were marked by an unease that could not be spoken aloud.

Officially, it was liberation.

In truth, it was a forced return to devastation.

The women packed the few belongings they had, a scarf knitted in captivity, a photograph of a guard’s child given in kindness, a notebook filled with diary entries about soap and corn and music.

Each item felt heavier than the suitcase that carried it, because each one represented a life about to vanish.

When the trains finally whistled, the sound carried both relief and dread.

The officers believed they were fulfilling duty.

The women felt they were stepping into exile, and as they climbed aboard, some with tears streaking their cheeks, the contradiction stood naked before history, freedom offered and refused in spirit.

For the gates of captivity were closing, but what waited beyond them was darker still, and soon the world would discover just how many begged not to be freed at all.

The first trains left the camps with groaning wheels and columns of smoke.

But what lingered most in memory were not the departures, but the faces pressed against the glass.

American guards, hardened by years of war, admitted later they had expected joy, or at least relief in the women’s expressions.

Instead, many looked stricken, their eyes fixed on the barbed wire, retreating into the distance as if they were being torn away from safety.

The paradox haunted the men who watched.

These prisoners had come as enemies, yet they left as reluctant exiles, clinging to captivity with a loyalty no one had imagined possible.

For some women, the petitions to remain had been written in neat script and handed nervously to officers.

They asked to continue their work in camp kitchens, to scrub floors, to tend gardens, to stay in America, even if it meant staying behind wire.

A few dared to propose bolder futures.

Marriage to a guard, contracts as domestic workers, lives lived in the very land that had once been painted as the face of the enemy.

Though regulations made such requests impossible, the act of writing them revealed something deeper.

Captivity had ceased to feel like punishment.

It had become a shield against a world in ruins.

The officers who read those requests struggled with the weight of them.

One captain in Kansas recalled his bewilderment.

We told them they were free, and they begged for their chains.

To him freedom was absolute, the natural longing of every prisoner.

But the women had come to measure freedom differently, not as the opening of a gate, but as the promise of safety, food, and dignity.

Those promises, paradoxically, lay not in Germany, but in the camps of the American Midwest.

Their strange loyalty to captivity was not rooted in love for America.

Though some women admitted an affection for its vast skies, its endless fields of corn, its music played on radios they could sometimes hear drifting from nearby towns.

What they loved was survival.

Behind the wire, they had learned once more what it meant to be warm, to be fed, to be treated as human beings rather than as burdens in a starving, bombed out nation.

One prisoner years later summed it up with quiet finality.

In America, I was a prisoner, but in Germany, I would have been nothing.

And yet, history did not allow for exceptions.

The Geneva Convention bound the United States to repatriation, and the machinery of war bureaucracy moved with implacable force.

Shiploads of prisoners sailed back to Bremerhavin and Hamburg, where families or strangers waited on gray docks.

Some clutching names on slips of paper, others standing in silence with hollow eyes.

The women stepped off the gang planks and were swallowed by a homeland unrecognizable, its streets blackened, its houses roofless, its people gaunt.

Those who had begged to remain in America found their worst fears confirmed.

Still, captivity had marked them in ways that endured.

A number of these women, once resettled, began to dream of returning, not to the barbed wire, but to the country that had surprised them with kindness.

In the 1950s, when immigration to the United States became possible again under special visas, some of those former prisoners applied eagerly.

A handful succeeded, crossing the ocean once more, this time not as captives, but as immigrants seeking the land where they had first tasted survival.

Their stories, scattered in oral histories and family records, testify to a peculiar truth.

The memory of captivity had become a bridge to belonging.

For those who remained in Germany, captivity lived on in memory as a season both bitter and strangely sweet.

They recalled the shame of defeat, the humiliation of being guarded, but also the shocking generosity of meals too plentiful to finish, the laughter over clumsy English phrases, the late night songs that rose into the prairie air.

These contradictions did not cancel each other out.

They coexisted, shaping a generation of women who had learned that freedom was not always simple, and captivity not always cruel.

The Americans, too, were changed.

Guards who had once feared or despised their prisoners carried home stories of women who cried at the thought of leaving.

One sergeant told his children decades later.

I saw the enemy asked to stay my prisoner.

That’s when I understood how broken their world was.

For him, the memory was not of triumph, but of tragedy.

The sight of young women holding on to prison fences as though they were lifelines.

Even within the camps, the women’s loyalty to captivity had a quiet, almost sacred dimension.

They tended their living spaces, planted small flowers outside the barracks, created order where none was required.

It was as if they sensed that while the fences lasted, they could carve out a fragile dignity, a community of survival.

to step beyond those fences meant to surrender all of that to a homeland where even roofs and bread were luxuries.

The barbed wire, once a symbol of oppression, had transformed into the outline of sanctuary.

The story is filled with irony too sharp to ignore.

American officers who believed in freedom as a gift were forced to watch their prisoners recoil from it.

German women who had once lived under a regime that promised a thousand years of glory now clung to the daily mercy of a foreign enemy.

Freedom meant hunger.

Captivity meant survival.

History delights in paradox, but few paradoxes cut as deep as this one.

And so the narrative circles back to those words spoken in 1945.

You can go home.

They were meant to open a door.

Yet for many they sounded like a sentence.

In the years that followed, some women did build lives again in Germany.

Others left as soon as they could, chasing the echo of the country, where, for the first time in years, they had known security.

Their loyalty to captivity was less about gratitude to America than about desperation, the human instinct to cling to safety wherever it might appear.

Even now the image remains vivid.

Women standing at the edge of the wire, eyes turned not east toward Europe, but west toward the horizon, the land they could not claim, yet could not forget.

Their loyalty to captivity was, in truth, loyalty to life itself.

It is a reminder that freedom is never merely the absence of chains, but the presence of dignity, safety, and hope.

And as the last gates clanged shut, the ships carrying them home already waiting, the question lingered in the air like smoke over a battlefield.

What did home truly mean to those who no longer recognized