Alershot, England, November 1945.

The medical tent smelled of antiseptic and canvas.

Rain drumed against fabric stretched over wooden frames.

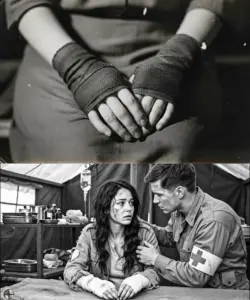

Sister Margaret Hoffman stood at attention, hands folded, eyes fixed on a point somewhere beyond the British officer’s left shoulder.

She’d been standing like this for what felt like an hour, but was probably 5 minutes waiting.

She was 23 years old, a qualified nurse from Hamburg who’d spent the last two years operating telegraph equipment for Vermacht Communications before being transferred to field hospitals in the final months.

Now she was a prisoner, one of thousands of German women captured when the Reich collapsed, women who wore uniforms but never fired weapons, women caught in the machinery of total war.

The British captain sat at his desk reviewing papers.

He had the weathered look of someone who’d been at this too long, someone who’d processed too many faces and heard too many stories.

When he finally looked up, his expression was unreadable.

“Name?” he asked in careful German.

“Hoffman, Margaret Hoffman, nurse Vermacht Medical Service.

” He made a note.

Standard procedure talking about down there, down there is our subscribe button.

[clears throat] Because what happened next was anything but standard.

To understand why Margareta stood trembling in that tent, why her heart hammered against her ribs, you need to understand what she’d been told would happen, what every German woman had been promised by 12 years of propaganda.

The stories started circulating in early 1945 as the Reich crumbled, whispered in bunkers, passed along evacuation routes.

AR spread through Vermacht Helerin and units like Contagion.

British soldiers, the rumors said, had special hatred for German women in uniform.

Women who’d enabled the war machine.

Women who typed orders, operated communications, freed up men for combat.

Nazi propaganda had spent years constructing an image of the British as cold, vengeful hypocrites.

Unlike the Americans, whom Gerbles painted as culturally inferior gangsters, the British were portrayed as calculating, methodical, cruel beneath a veneer of civilization.

For German women specifically, the messaging was darker.

They would be singled out, humiliated, made examples of what happens to women who step beyond their place.

Margaret had joined the Vermarked medical service in 1943, not out of ideological fervor, but because it was that, or factory work.

The daughter of a school teacher she’d trained as a nurse before the war, had wanted to help people.

The uniform gave her that chance, even as it bound her to a system whose full horror she was only beginning to comprehend.

By April 1945, her field hospital near Bremen was in chaos.

Wounded arrived faster than they could be treated.

Supplies ran out.

Officers disappeared.

On May the 7th, a British unit arrived.

Margaret and the other nurses lined up outside, uncertain, terrified.

This was the moment, the reckoning they’d been promised.

Instead, a young British sergeant walked down the line with a clipboard, taking names.

He was professional, almost bored.

He asked their names, their training, whether anyone was injured.

nothing more.

They were processed, loaded onto trucks, taken to a transit camp.

No violence, no retribution, just bureaucracy, efficient and indifferent.

But the fear remained because maybe that was the trick.

Maybe the real punishment came later.

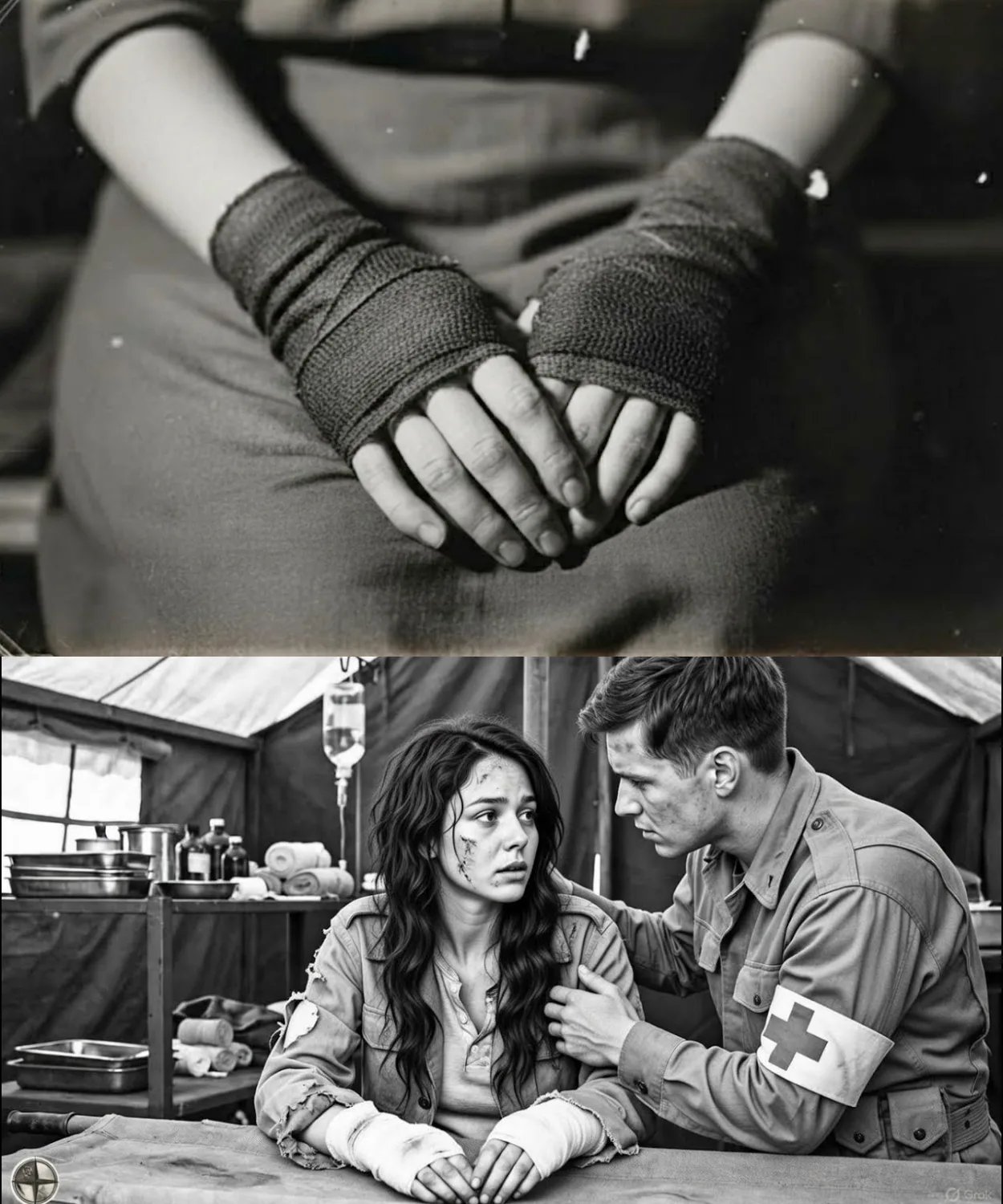

Now, 6 months into captivity, Margaret stood in this medical tent because her nursing training meant she’d been assigned to work in the camp infirmary.

The British needed medical personnel.

German or not, qualified nurses were qualified nurses.

She’d spent the past month assisting a British medical officer, Captain Morrison, a 40-year-old army doctor who treated everyone, prisoner and guard alike, with the same clinical competence.

Morrison terrified her, not because he was cruel, but because he wasn’t.

He gave orders in German, corrected her technique when she botched a suture, thanked her when she worked late.

He was professional, human.

It didn’t fit.

The captain reviewing her papers cleared his throat.

Margarett’s attention snapped back.

He was looking at her now.

Really looking not at her uniform or her prisoner number, but at her face.

You worked at the Bremen Field Hospital, he said.

Not a question.

Yes, sir.

April 1945, the final weeks.

Margaret’s throat tightened.

Here it came.

Whatever this was, whatever he’d been building toward, “There was a convoy,” he continued, voice careful, “British wounded men we’d recovered from a German P camp that had been liberated.

They came through your hospital for initial treatment before being evacuated.” She remembered, “Cha, those days.

British soldiers on stretchers, emaciated, injured, some dying.” Her supervisor had ordered the German staff to treat them anyway, even as their own wounded piled up untreated.

At the time, Margaret hadn’t questioned it.

“You helped who was in front of you.” “That was nursing.” “Yes,” she said quietly.

“I remember.” The captain pulled a photograph from his file, placed it on the desk.

A young man in uniform, smiling, probably 18 or 19, before the war left its marks.

Private James Fletcher.

The captain said he was one of the men who came through your hospital.

Dissantry, malnutrition, infected leg wound from being held in Stalagatu a records show you were the one who treated him.

Margaret stared at the photograph.

She didn’t remember faces.

There’d been too many.

British, German, it didn’t matter.

Just bodies that needed help.

I treated many British soldiers, she said carefully.

I don’t remember specific names.

The captain’s expression softened just slightly.

He remembered you.

When he was debriefed after evacuation, he mentioned the German nurse at Braymond who spent her lunch breaks changing his dressings because the regular shifts were overwhelmed.

Who gave him extra water even though she wasn’t supposed to? Who told him in broken English that she was sorry.

Something cold twisted in Margaret’s chest.

She did remember now.

Not his face, but the feeling.

The British boy on the stretcher, 17 maybe, delirious with fever, calling for his mother in his sleep.

She’d stayed late that night, sponging his forehead with cold water, monitoring his fever because no one else had time.

Not because he was British or German, but because he was dying and alone and someone should be there.

He made it home, the captain said.

Thanks in part to you.

He asked me to find you if I could to say thank you.

Margaret couldn’t speak, couldn’t process what she was hearing.

If you’re still watching, you’re clearly a history lover.

Hit that subscribe button because what happens next shows how one small act of humanity echoes across the wreckage of war.

The captain closed the file.

You’re being reassigned, Sister Hoffman.

Captain Morrison requested you specifically for his medical team.

You’ll work in the camp hospital, treating both prisoners and British personnel.

standard wages, proper accommodations, medical training opportunities if you’re interested.

She found her voice.

Why? Because Morrison says you’re competent.

Because we need nurses.

Because Private Fletcher’s letter specifically asked that you be treated well if found.

He paused.

And because treating people decently is what separates us from what we fought against.

It was the closest anyone had come to acknowledging the larger horror, the camps, the systematic murder, the things Margaret was only now beginning to understand the full scope of things she’d been part of, however peripherally, by serving the system that enabled them.

I didn’t know, she said, the words inadequate even as she spoke them.

We didn’t.

I know, the captain interrupted, not unkindly.

Or you suspected but didn’t ask.

It’s complicated, but you did what you could with the knowledge you had.

That boy lived because you cared enough to stay late.

That matters.

He stood extending his hand.

British officers didn’t shake hands with prisoners, but he did.

After a moment, Margareta took it.

Welcome to the medical team, Sister Hoffman.

3 months later, in February 1946, Margaret stood in the camp hospital treating a young British soldier who’d slipped on ice and broken his arm.

Morrison was teaching her British medical protocols, better suturing techniques, things she’d never learned in German training.

The work was exhausting, the pay minimal, but she had purpose.

Function.

One afternoon, a packet arrived, forwarded through official channels sealed with British military stamps.

Inside, a letter from Private James Fletcher, now recovered, now home in Yorkshire.

He wrote about the farm he’d returned to, about his family, about how strange England felt after years in captivity.

And he thanked her again for the water, for staying, for being human when the world had forgotten how.

Margaret read the letter three times, then carefully folded it and placed it in her foot locker alongside the identification papers that would eventually allow her to return to whatever was left of Germany.

That evening, she asked Morrison a question that had been building for months.

Why do you do this? Treat us the same as your own soldiers.

We’re the enemy.

We enabled everything that happened.

Morrison was cleaning instruments, methodical, precise.

He didn’t look up.

Because if I let hatred dictate my medicine, I become what we fought against.

Because you can’t build a better world by repeating the mistakes of the one you just tore down.

He glanced at her.

And because you’re not the enemy, you’re a nurse who happened to serve the wrong government.

There’s a difference.

And if you’re enjoying this deep dive, subscribing helps us keep making stories like this.

By summer 1946, the camp had established routines that felt dangerously close to normal.

Margaret had been promoted to senior nursing staff, supervising other German nurses who’d been cleared for medical work.

She trained them the way Morrison had trained her, passing along British protocols, insisting on standards, even when treating prisoners.

One day, a new batch of PS arrived.

Vermarked soldiers captured late, held initially in rougher camps on the continent.

Among them, several injured, including a young woman, maybe 19, with infected shrapnel wounds from the final battles.

Her name was Anna.

She’d been a signals operator, same as Margaret, years before.

Anna was terrified.

She’d heard the stories, the ones Margaret herself had believed, what the British did to German women, what waited for prisoners.

Margaret cleaned the girl’s wounds with practiced efficiency, administered sulfur drugs, wrapped clean bandages.

Anna watched her with wide, frightened eyes.

“It’s not what they told us,” Anna whispered.

“The British.

They’re not.” “No,” Margaret said quietly.

“They’re not.” She thought about Private Fletcher, about Morrison’s patient hands teaching her sutures, about the captain who’d remembered her name because a boy she’d helped asked him to, about a system that could have taken vengeance and chose structure instead.

They’re trying to prove something, Margaret continued, securing the bandage.

That civilization means something.

That you can win a war without becoming what you fought against.

Whether they’ll succeed, I don’t know, but they’re trying.

Anna looked at her with something like hope.

Margaret recognized that expression.

She’d worn it herself six months ago, standing in a tent, waiting for punishment that never came.

If you’ve made it this far, hit subscribe so you don’t miss what comes next.

Repatriation came in stages.

The British government, under pressure from Parliament and humanitarian groups, began processing German PS for return in late 1946.

Margaret’s name came up in January 1947.

On her last day at the hospital, Morrison called her into his office.

He handed her an envelope.

Inside, a reference letter typed on official military stationery.

It detailed her training, her work at the camp hospital, her competence and professionalism.

It was signed by Morrison and countersigned by the camp commandant.

For whoever’s hiring in Germany, Morrison said, “You’ll need it.

Not many nursing positions left.” and they’ll question anyone who served the vermarked.

Margareta held the letter like something fragile.

Captain Morrison, I don’t, he interrupted.

Don’t thank me.

You earned this.

Just take it.

Go home and build something better than what you left.

She wanted to say something about the impossibility of that task, about the ruins waiting in Germany, about the guilt that sat in her chest like a stone.

But Morrison knew.

He’d seen it in every German prisoner who passed through his hospital.

The moment they realized what their country had become, what they’d been part of, instead she said the only thing that mattered.

I’ll try.

The transport truck left on a cold January morning in 1947.

Margaret sat with 30 other women, all processed, all cleared, all heading back to a Germany divided among victors.

As the camp gates disappeared behind them, she thought about the boy on the stretcher, the one who’d remembered her name, about the captain who’d found her because someone had asked him to, about Morrison’s steady hands and refusal to let hatred guide his medicine.

The British could have destroyed them, could have taken revenge for 6 years of war, for the bombing, for the camps, for the systematic murder of millions.

They had every right.

Instead, they’d chosen something harder, something that required more discipline than vengeance ever could.

They’d chosen to practice what they preached.

When Margaret finally reached Hamburg, she found ruins.

Her family’s home was gone, destroyed in the 1943 firestorms.

Her father dead, her brother missing, presumably dead in Russia.

But she had Morrison’s reference letter, and she had training.

and 6 weeks later she found work at a Soviet administered hospital in the British sector.

The work was brutal.

Resources were scarce.

The city was rubble, but she was needed and that mattered.

Years later, in 1952, Margaret received another letter forwarded through official channels.

Private Fletcher, again, now married, now a father, working his family’s farm in Yorkshire.

He’d found her through the Red Cross, wanted to know if she was alive, if she was all right.

She wrote back.

They corresponded for years.

Letters crossing between two people who’d met in the worst moment of their lives and somehow found connection across the wreckage.

He never came to Germany.

She never went to England.

But the letters continued, a quiet acknowledgement that even in total war, individual humans could choose to see each other’s humanity.

In her 60s, Margaret would tell her children about the war, about the mistakes, about serving a system that committed atrocities she still struggled to comprehend.

She told them about the British camps, about expecting monsters and finding humans instead.

About the captain, who’d remembered her name because a boy she’d helped had asked him to.

The hardest thing, she told her daughter one evening in 1972, wasn’t the confinement or the work.

It was realizing that everything we’d been taught about the world was a lie.

That the enemy could be more humane than we’d ever been.

That kindness could be a weapon more powerful than any bomb.

Her daughter asked the question that haunted her generation.

Did we deserve it? The kindness, I mean, after everything we did.

Margaret was quiet for a long time.

No, she said finally.

We didn’t deserve it.

That’s the point.

They gave it anyway.

They chose to prove that civilization wasn’t just propaganda.

That it actually meant something.

That you could win a war without becoming what you fought against.

Whether we deserved it or not, they demonstrated what we should have been.

And that, she paused, that was the most devastating thing they could have done.

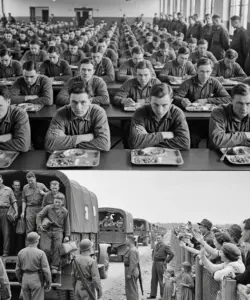

Between 1945 and 1948, Britain held approximately 400,000 German prisoners of war, including several thousand women from vermarked auxiliary services.

The treatment varied between camps.

Conditions weren’t perfect.

Some guards harbored resentment.

But compared to what German prisoners faced in Soviet hands, compared to what Allied prisoners had endured in German camps, Britain’s approach was revolutionary.

They followed Geneva Convention protections.

They provided medical care.

They paid wages.

They treated prisoners according to rules Germany had never followed for its own captives.

This wasn’t altruism.

Britain needed labor for reconstruction.

They needed Germany to rebuild as a democratic nation.

They needed to prove that Western civilization could offer something better than fascism.

But for the women who experienced it, for the vermarked Helerinan who expected brutality and received structure, the effect was profound.

Many maintained contact with British families they’d worked for.

Some married British soldiers.

Others like Margaret went home carrying lessons about what civilization actually meant.

The phrase that haunted their testimonies was simple.

Who told you my name? That moment when a British officer knew not just their prisoner number, but their name, their story, their humanity.

That moment when they realized the enemy had seen them as people, not as representatives of a hated system.

This wasn’t the dramatic story of combat.

It was the quiet story of its aftermath.

Of how Britain chose to wield victory not through revenge, but through demonstrating that the values they’d fought for actually meant something.

Of how a captain could remember a nurse’s name because a boy she’d helped asked him to.

Of how routine fairness and stubborn insistence on following rules could be more devastating to totalitarian ideology than any propaganda campaign.

Margaret Hoffman died in 1998.

At her funeral, her children found Morrison’s reference letter carefully preserved in a wooden box alongside Fletcher’s correspondence.

Also in the box, her vermarked identification papers and her British P release documents.

A record of the woman she’d been and the woman she’d become.

If this story moved you, please share it.

These accounts deserve to be remembered.

They remind us that even in the darkest times, individual humans can choose to see each other’s humanity.

That choice made again and again by ordinary people is how the world actually changes.

That’s how a German nurse learned her name still mattered.

That’s how a British captain proved civilization wasn’t just a word.

That’s how two people on opposite sides of total war found their way back to something human.

Who told you my name? Someone who remembered.

Someone who chose to see past the uniform to the person beneath.

Someone who understood that peace isn’t just the absence of war.

It’s the hard daily work of treating enemies as if they could become something else.

And sometimes in the rubble of everything, that’s exactly what they become.