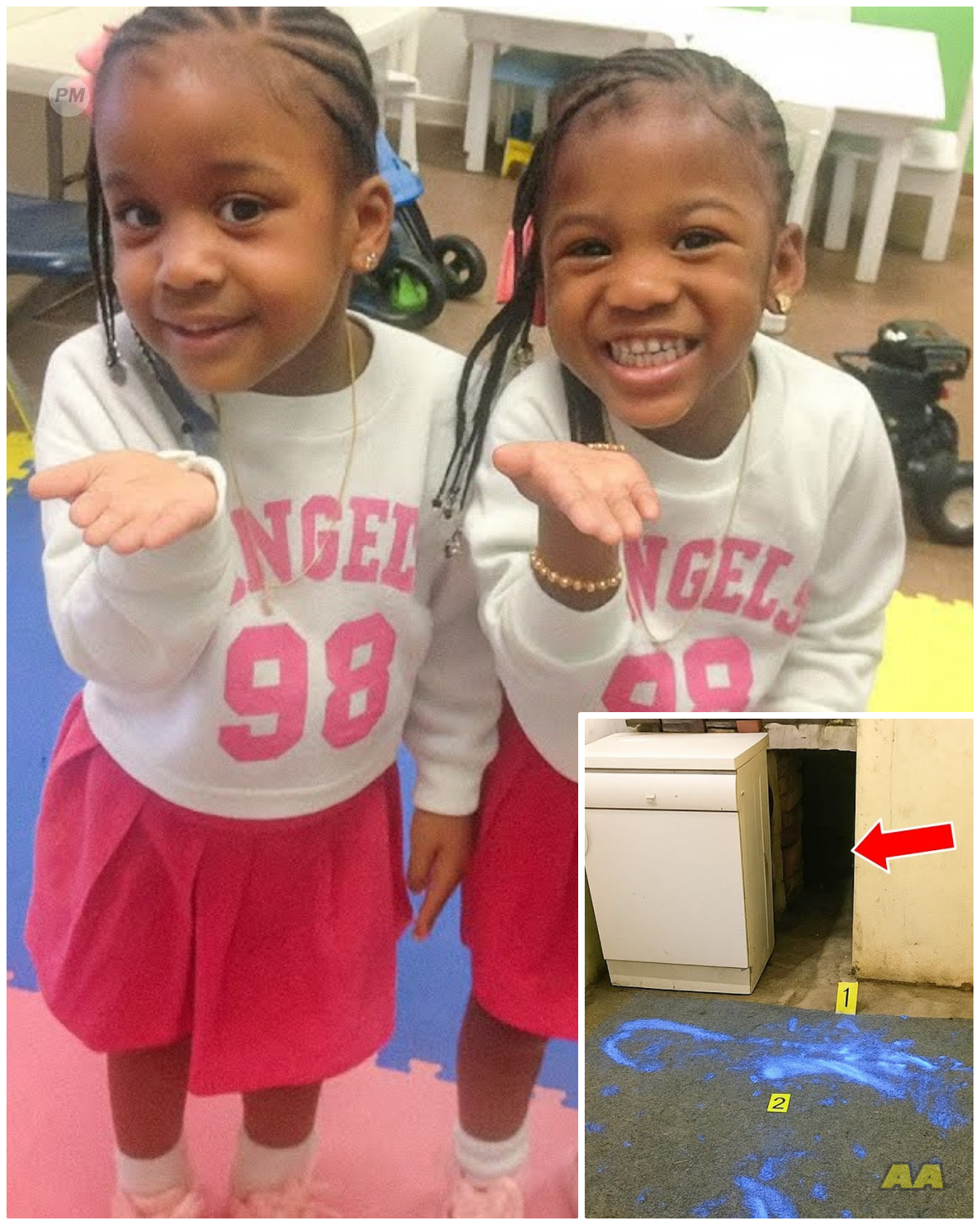

This 1884 studio portrait looks proud until you see the seamstress’s hand.

At first glance, it is simply another example of a successful artisan posing with his protege.

A moment of professional accomplishment preserved on glass.

But one detail refused to stay hidden, and that detail would unravel a century of carefully maintained lies about the Paris fashion industry’s most celebrated era.

Dr.

Emily Boddan discovered the photograph on a February morning in 2019 while cataloging a donation to the Musea Desar Decoratif.

The collection had come from the estate of a descendant of Charl August Renard, a second tier tailor who operated in Atella in the 10th Aaron Disma during the 1880s.

Emily had spent 15 years studying the material culture of Bella Punk fashion, and she had learned to read these staged portraits with a skeptical eye.

The poses were always too perfect, the smiles too fixed, the relationships too cleanly hierarchical.

But this image stopped her cold.

The photograph showed Renard, a man in his early 50s with a well-groomed beard and confident posture, standing beside a seated young woman who appeared to be in her early 20s.

She wore a dress of remarkable quality, dark silk with intricate pleading at the bodice and sleeves.

Her hair was styled in the fashion of the period, swept up and backard’s hand rested on her shoulder in what seemed to be a gesture of paternal pride.

The studio backdrop featured painted columns and drapery, standard props meant to convey classical refinement.

The young woman’s expression was harder to read.

Her face was composed, neither smiling nor frowning, but there was something in the set of her jaw that suggested tension.

Her posture was rigid.

And then Emily noticed her hands.

They were positioned carefully in her lap, one resting on top of the other, both encased in sheer evening gloves, but the gloves were not opaque enough to hide what lay beneath.

Even in the faded album print, Emily could see darker spots on the fingertips.

She moved the photograph under the magnifying lamp on her desk and increased the light.

The spots became clearer.

They were wounds.

Dozens of tiny punctures, some fresh enough that slight discoloration suggested blood pooling beneath the translucent fabric.

The woman’s fingertips were destroyed.

Emily set down the magnifying glass and stared at the image.

This was not just a pretty old photo.

Something here was profoundly wrong.

Emily had seen thousands of 19th century photographs in her career.

She specialized in images related to the textile and garment trades, particularly those that documented the rise of oat couture in Paris.

The 1880s were considered a golden age, the moment when Paris cemented its reputation as the fashion capital of the world.

Worth Pingot, Duce and dozens of smaller atalieres employed thousands of workers to produce the elaborate gowns that dressed European aristocracy and the emerging American upper class.

The public narrative celebrated the artistry, the innovation, the French genius for beauty.

Museum exhibitions, including several that Emily had helped curate, perpetuated this narrative.

But Emily had also read the labor historians.

She knew what those exhibitions usually omitted.

The 12-hour days, the unheated workrooms, the wages so low that many seamstresses could barely afford bread.

the young women often migrants from rural France or neighboring countries who disappeared into the Italas and were never heard from again.

The supposed apprenticeships that amounted to bonded labor.

The tuberculosis, the malnutrition, the mysterious deaths that were noted in parish records but never investigated.

Still, even knowing all of this, she had never seen it made so visible in a photograph.

The studio portrait was a tool of propaganda.

It was meant to show success, respectability, the orderly transmission of craft knowledge from master to student.

It was not meant to reveal the cost.

Emily carefully removed the print from its backing board.

The photograph had been mounted on thick card stock with Renard’s studio information printed at the bottom.

See Renard Tyure 48 Rudu Fobborg Sanden Paris.

On the reverse side, someone had written in faded ink.

Renard Asa Jeanvier 1884.

Renard and his apprentice, January 1884.

No name for the young woman.

There was also a stamp partially obscured by age and handling that appeared to be from a photographer’s studio.

Emily could make out part of the text.

Attelier photographic Mororrow.

She recognized the name.

Henri Moro had operated a successful portrait studio on the Boulevard Distraborg during the 1880s and 90s.

His specialty was commercial photography for businesses, advertising images that made small operations look grand and successful.

He was known for his ability to make a cramped workshop appear spacious, to make tired workers look content.

The more Emily looked at this photograph, the more her professional curiosity hardened into something closer to moral obligation.

If she filed this image away in the archive without investigating further, a story would remain buried.

Someone, a young woman whose name had not even been deemed worth recording, had sat for this portrait with her hands literally bloodied by her work, and the man beside her had posed as her benevolent mentor.

Emily opened her laptop and began with the simplest searches.

The Paris city directories from 1884 confirmed that Charl August Renard maintained a business at the Rude Du Faborg Sentini address.

He was listed as a tailor specializing in women’s clothing.

The same directories showed that his business operated at that location from 1878 until at least 1892, which suggested a degree of stability and success.

She moved on to the Paris Chamber of Commerce records, which were partially digitized.

Renard appeared in several reports from the 1880s.

He had presented at an industrial exhibition in 1885, showing examples of his work alongside other small manufacturers.

A brief mention in a trade journal from 1887 noted that the atalier of Msure Renard continues to produce garments of refined taste, employing a staff of skilled workers in the execution of designs for the discerning clientele.

On the surface, it was the story of a small but respectable business.

Nothing remarkable, but nothing suspicious.

Emily reached out to Lauron Marshall, a historian at the Sorbone, who had written extensively about labor conditions in the Paris garment industry during the Third Republic.

She sent him a highresolution scan of the photograph and a brief description of what she had noticed.

Lauron called her the next morning.

His voice was tight with recognition.

“I have seen this before,” he said.

“Not this exact photograph, but others like it.

There is a pattern.” He explained that during the 1880s and ’90s, as labor agitation increased and socialist newspapers began publishing exposees about working conditions, some employers commissioned photographs specifically to counter the accusations.

The images showed clean workshops, well-dressed workers, and relationships that appeared familial rather than exploitative.

These photographs circulated among business associations and were sometimes published in trade journals as evidence that the garment industry treated its workers well.

But if you look closely, Lauron continued, you start to see the cracks.

The workers are always posed in ways that suggest subordination, even when the caption claims partnership.

The settings are always studios, never the actual workrooms, and sometimes there are details that the photographer and the employer did not think to hide because they were so normalized that no one saw them as evidence of abuse.

Emily asked about the bleeding hands.

Lauron was quiet for a moment, then he said it was called the cost of learning.

The masters would say that an apprentice’s fingers had to toughen, that the pain was temporary, that any girl who complained simply lacked the dedication required for fine work.

But we have medical records from the period.

Doctors treating seamstresses described chronic infections, nerve damage, deformities of the fingertips from repeated needle punctures.

Some women lost the use of their hands entirely by their 30s.

He paused, then added, “The sheer gloves are interesting.

They were fashionable, yes, but they also allowed the wounds to be visible while maintaining the appearance of propriety.

Renard probably thought he was demonstrating her diligence.

He would not have seen it as evidence of abuse.

Emily felt something cold settle in her stomach.

She asked Luron if he could help her find records specific to Renard’s Attelier.

He agreed to check the archives of the Paris Prefecture of Police, which maintained files on businesses suspected of labor violations, as well as the records of several mutual aid societies, that provided assistance to garment workers in distress.

3 weeks later, Lauron sent Emily a thick folder of documents.

Most were photocopies of handwritten records, some barely legible, but together they began to fill in the gaps.

The prefecture of police had received two complaints about Renard Zatellier.

One in 1883 and another in 1886.

Both came from neighbors who reported hearing screams and sounds of physical violence late at night.

In each case, an officer visited the premises, spoke with Renard, and filed a report stating that the household was orderly and that no evidence of wrongdoing was found.

The reports noted that Renard employed several young women in the capacity of apprentices who reside on the premises and receive instruction in exchange for their labor.

The mutual aid society records were more revealing.

In 1884, the same year as the photograph, a woman named Marie Dvos sought assistance from the Soete de Sukur’s Muchel de Zuier.

She was 19 years old, originally from a village near Leil in northern France.

The intake form described her as formerly in the service of Taylor C.

Renard, now unable to work due to illness and destitution.

The nature of her illness was not specified, but the form noted that her hands were severely damaged and that she had se had scars on her arms that appeared to be from beatings.

There was no indication of what happened to Marie Dvas after she sought help from the society.

Her name did not appear in any subsequent records Emily could find, but there were others.

Over the next several months, Emily traced references to four more young women who had worked for Renard between 1880 and 1890.

Two had been admitted to the Opal Larib Buisier with tuberculosis and malnutrition.

One had died there.

The hospital records described them as seamstresses without family or resources.

None of the official records used the word slavery, but Lauron explained that the system had its own vocabulary.

These young women were called apprentices, but the term had been emptied of its traditional meaning.

In a legitimate apprenticeship, the master provided training and the apprentice provided labor.

But there was a defined period of learning and a path to independence.

What Renard and others like him practiced was something different.

They recruited girls from impoverished rural areas, promising training in a prestigious trade in a position in Paris.

The contracts, when they existed at all, stipulated that the apprentice would receive room and board in exchange for work.

There was no mention of wages.

The term of service was vague, often described as until such time as the master deems the apprentice sufficiently skilled.

In practice, that time never came.

The young women lived in cramped quarters, often in the attic or basement of the building where the Attelier operated.

They worked from dawn until late into the night, producing the garments that Renard sold under his own name.

If they tried to leave, he would claim they owed him money for their lodging and food, debts that could never be repaid on the wages he refused to pay.

If they persisted, he would threaten to report them to the police for theft or breach of contract.

Many had no papers, no family in Paris.

no resources to challenge him.

Lauron called it debt bondage with a bourgeoa face.

It was not the chatt slavery that had been abolished in French colonies decades earlier, but it functioned on similar principles.

Human beings treated as assets, their labor extracted through a combination of legal coercion and physical control.

Their suffering hidden behind the respectable facade of an artisan’s workshop.

Millie traveled to the Rudu Faborg Sandini to see the building where Renard Zaitella had been located.

The address still existed, though the ground floor was now occupied by a shop selling mobile phones.

The architecture was 19th century, tall and narrow with ornate iron work on the balconies.

She stood on the sidewalk and imagined the young women who had lived and worked in that space.

How many hours had they spent hunched over needle work and dim light? How many times had they heard footsteps on the stairs and felt their stomachs clench with fear? The current owners of the building knew nothing about its history.

There was no plaque, no marker, nothing to indicate what had happened there.

Back at the museum, Emily continued to search for any trace of the woman in the photograph.

She went through census records, baptismal records, death records.

She contacted local historians in the regions where Renard was known to have recruited workers.

She posted inquiries on genealogy forums asking if anyone had ancestors who worked in the Paris garment trade during the 1880s.

One response came from a woman named Isabelle Maro who lived in Leil.

She explained that her great great grandmother had left their village in 1882 to work as a seamstress in Paris.

The family had received a few letters in the first year, then nothing.

They never learned what happened to her.

Her name was Celeste Mororrow and she had been 17 when she left.

Emily asked if Isabelle had any photographs.

She did not, but she sent a description that had been passed down through the family.

Celeste had been small with dark hair and a serious expression.

She had been skilled with a needle from a young age helping her mother with mending and dress making in the village.

It was impossible to confirm whether Celeste Maro was the woman in the photograph, but the timeline matched and the name Maro connected to the photographers’s studio in an eerie coincidence that may have been nothing or may have been everything.

Emily drafted a research note and submitted it to a journal specializing in labor history.

The article described the photograph, the evidence of exploitation, and the broader pattern of abuse disguised as apprenticeship in the Bell Epoke garment industry.

It was peer- reviewviewed and accepted for publication.

But Emily wanted to do more.

She proposed an exhibition at the Muse Desar Decoratif that would reframe the museum’s collection of fashion photography from the period.

Instead of celebrating the artistry and elegance, the exhibition would foreground the labor that made it possible.

The photograph of Renard and the unnamed seamstress would be the centerpiece.

The proposal went to the museum’s curatorial committee in June 2020.

The meeting was held over video conference due to pandemic restrictions which somehow made the conflict feel both more distant and more intense.

The director of collections, Bertrron Lefv, spoke first.

He acknowledged the importance of Emily’s research but expressed concern about the tone.

We must be careful, he said, not to impose contemporary moral judgments on the past.

These were different times.

The economic realities were different.

We risk a alienating visitors, particularly our donors, if we present the history of French fashion as fundamentally exploitative.

Emily kept her voice steady.

The exploitation was real, she said.

We have documented evidence, hospital records, police reports, testimony from mutual aid societies.

These women were not simply enduring difficult working conditions.

They were trapped in a system that treated them as disposable.

And this photograph is evidence of that system.

The bleeding hands are right there in the image.

Renard posed with her injuries visible because he did not see them as shameful.

He saw them as proof of her dedication to learning his craft.

Another committee member, a fashion historian named Sophie Gerard, spoke up.

But do we know for certain that this woman was coerced? Perhaps she was a willing apprentice who accepted harsh conditions because she wanted the opportunity.

Many people in that era endured suffering to achieve their goals.

Emily pulled up the records on her screen and shared them with the group.

We know that multiple women fled Renard’s Atelier.

We know that at least one sought help from a charity describing beatings.

We know that two were hospitalized with conditions consistent with long-term malnutrition and overwork.

We know that none of them were paid wages.

We know that Renard photographed them as propaganda to counter accusations of abuse.

None of that suggests willing participation.

The head of development, Claire Dubois, raised a practical concern.

Several of our major donors have family connections to the fashion industry.

Some of their ancestors operated similar atalieres during this period.

If we mount an exhibition that explicitly frames these business owners as exploiters, we risk offending people whose support is critical to the museum’s operations.

Lauram Marshand, who Emily had invited to participate as a consulting historian, leaned into his camera.

With respect, he said, “We are not discussing whether someone’s feelings might be hurt.

We are discussing whether to tell the truth about what happened to real people who suffered and died.

These women have been erased from history.

Their names do not appear in any of the celebratory accounts of Bella Pac fashion.

The only trace many of them left is in hospital records and police files described as anonymous seamstresses without resources.

This photograph is one of the few pieces of visual evidence that captures both the public lie and the hidden reality.

If we do not use it to correct the record, we are complicit in the eraser.

The silence that followed was heavy.

Emily watched the faces in the video grid.

Some looked uncomfortable.

Some looked defensive.

A few looked like they were genuinely reconsidering their positions.

Bertrren spoke again.

I’m not opposed to examining difficult aspects of history, but I want to ensure that we do so with nuance.

Perhaps we can present multiple perspectives, show the photograph, explain what you have found, but also include information about the legitimate apprenticeships that did exist, the women who did find success in the fashion industry, the ways in which this was a complex system with both exploitation and opportunity.

Emily felt a flash of anger, but kept it out of her voice.

Complexity is important, she said, but we cannot use it as an excuse to soften the truth.

Yes, some women found success, but this photograph is not about them.

This photograph is about a specific young woman whose bleeding hands are visible in the image and a specific tor who presented her suffering as evidence of his benevolence.

If we surround that image with caveats about complexity, we dilute its power.

We give viewers permission to look away.

The committee debated for another hour.

In the end, they agreed to move forward with the exhibition, but with conditions.

Emily would have authority over the curatorial content, but the museum would include an introductory wall text that contextualized the exhibition within the broader history of French fashion.

The text would acknowledge both the innovation of the period and the human cost.

It was not everything Emily wanted, but it was enough.

The exhibition opened in March 2021.

As the city was cautiously emerging from pandemic lockdowns, it was titled the hidden seams, labor and image in Beloke, Paris.

The photograph of Renard and the seamstress hung in the first gallery, enlarged to nearly life-size so that the wounds on her hands were impossible to miss.

The wall text began with a question.

What does this photograph want you to see? It explained that studio portraits from the 1880s were carefully constructed performances designed to project respectability and success.

It pointed out Renard’s confident posture, the quality of the seamstress’s dress, the classical backdrop.

Then it directed the viewer’s attention to the hands, the sheer gloves that failed to hide the puncture wounds, the careful positioning that suggested she had been told to display them.

text quoted from the hospital records and mutual aid society documents using the actual words of the people who had treated and tried to help these women.

It explained the system of debt bondage, the contracts that trapped young migrants in unpaid labor, the violence that enforced compliance.

It noted that Renard’s Attelier was not unique, that dozens of similar operations existed in Paris during this period, and that the fashion industry’s celebrated output rested on the exploitation of workers whose names and faces were deliberately erased from the historical record.

The centerpiece of the exhibition’s final gallery was a collaborative project between Emily and several descendants of garment workers from the period.

They had collected oral histories, family letters, and records from working-class organizations that told the story from the perspective of the women themselves.

One of the contributors was Isabelle Maro, who had provided everything her family knew about Celeste’s disappearance.

The exhibition included a letter that Celeste had sent to her family in 1883, found among parish records in Le.

It was brief and carefully worded, but between the lines, the desperation was clear.

I’m learning much from Ms.

Renard, she wrote.

The work is difficult, but I’m told this is necessary for mastery of the craft.

I’m often tired, but I’m assured this will pass.

I think of home and hope to visit when I’m able to afford the journey.

There was no record of whether she ever made that journey, but there was a death certificate for a Celeste M.

Seamstress, age unknown, who died at the Opal Laribazier in 1885 was listed as pulmonary consumption.

The hospital records noted that she had no family or resources and that her body was released to the medical school for anatomical study.

Emily stood in the gallery on opening day and watched visitors move through the space.

Some spent a long time in front of the photograph, leaning in to examine the hands, then stepping back to take in the whole composition.

Others seemed shaken, pausing to read and reread the wall text as if they could not quite believe what it said.

One woman, perhaps in her 70s, stood in front of the photograph for nearly 20 minutes.

When she finally moved on, she approached Emily, who was standing nearby.

“My grandmother worked in a sewing workshop in Paris,” the woman said quietly.

“She never talked about it, but my mother told me that she would wake up screaming sometimes.

Her hands were scarred.

I always wondered what happened to her there.” Emily did not know what to say that would not sound inadequate.

She simply nodded and thanked the woman for sharing that.

The exhibition attracted significant media attention.

Several major newspapers published features about it.

A documentary filmmaker approached Emily about developing the story for television.

The museum reported record attendance for an exhibition focused on labor history.

But there was also backlash.

Two donors withdrew their support, issuing statements that accused the museum of presenting a politicized and one-sided view of history.

A conservative magazine published an editorial arguing that the exhibition was part of a broader trend of condemning the past according to contemporary standards and that it failed to appreciate the economic constraints and social norms of the 19th century.

Emily read these critiques with a mix of frustration and resignation.

She understood that telling uncomfortable truths would provoke discomfort, but she also knew that the alternative was worse.

The alternative was allowing the lies to stand, allowing Charles Agugust Renard to remain a respectable artisan in the historical record, allowing the young woman with the bleeding hands to remain nameless and forgotten.

The exhibition ran for 6 months.

When it closed, the photograph was placed in the museum’s permanent collection with a detailed provenence note that included all of Emily’s research.

It would be available for future scholars, future exhibitions, future reckonings with the past.

Lauron Marshon published a follow-up article that used the photograph as a starting point for a broader analysis of how visual culture from the Bell Poke had sanitized and obscured labor exploitation.

He documented dozens of similar images, portraits that showed workshop owners with their supposed apprentices, all posed to suggest harmonious and productive relationships.

In many of the images, small details told different stories.

A child’s hollow cheeks, a man’s grip on a young woman’s shoulder that looked less paternal than possessive.

Background elements that suggested confinement rather than collaboration.

Emily continued her work at the museum, but the photograph changed how she looked at everything in the collection.

She began to notice patterns.

The absence of working hands and images of luxury goods.

The careful framing that excluded the spaces where production actually happened.

The way that captions and labels attributed creation to individual masters while erasing the workers who did the physical labor.

She started a new research project focused on recovering the names and stories of anonymous workers in fashion photographs from the period.

It was painstaking work, cross- refferencing census records, hospital admissions, police reports, and church registries.

Most of the time, she hit dead ends.

But occasionally, she found a name, a birthplace, a fragment of a story.

Each name felt like a small act of restoration.

Old photographs are not neutral documents.

They are constructed images staged to convey specific messages to specific audiences.

In the case of commercial and industrial photography from the 19th century, those messages were almost always about power.

They showed who was supposed to be respected, who was supposed to be subordinate, what relationships were supposed to look like.

But photographs also betray their creators.

Small details slip through that were not meant to be seen or that were so normalized that no one thought to hide them.

A child positioned like property, hands damaged by labor, an expression that does not match the happy narrative.

These details are not accidents.

They are evidence.

Evidence of what was done to people whose names were not recorded, whose suffering was not acknowledged, whose humanity was treated as incidental to the smooth functioning of an economic system.

The 1884 portrait of Charlo’s Agugust Renard and his unnamed apprentice hangs now in the Musa Dear Decoratif with a label that tells a very different story than the one Renard intended.

It is no longer a testament to his skill as a tailor or his generosity as a mentor.

It is evidence of exploitation.

It is proof that the elegant garments of the Bella Epoch were stitched with the blood of young women who had no other choice.

And it is a reminder that the images we inherit, the photographs that fill our textbooks and family albums and museum walls often hide as much as they reveal.

The work of the historian, the curator, the researcher is not simply to collect and preserve these images.

It is to read them against the grain.

To ask who is missing from the frame, to notice the details that were meant to be invisible, to recover the stories that were meant to stay buried.

Because every photograph is also an absence.

Every proud portrait of a master craftsman is also a photograph of the people whose labor made his success possible.

Every image of progress and prosperity is also evidence of who paid the price for that progress.

The seamstress in Renard’s photograph deserved more than to be a nameless prop in someone else’s story of triumph.

She deserved to have her suffering acknowledged, her resistance, however small and doomed, recognized, her humanity restored.

That restoration is incomplete.

We do not know her name with certainty.

We do not know the full arc of her life.

We do not know if she ever escaped or if she died young in a hospital ward or if she simply disappeared into the vast silence that swallowed so many lives.

But we know she was there.

We know she bled.

We know she endured.

And we know that someone decades later refused to look away from what the photograph revealed.

That is not everything.

But it is not nothing.