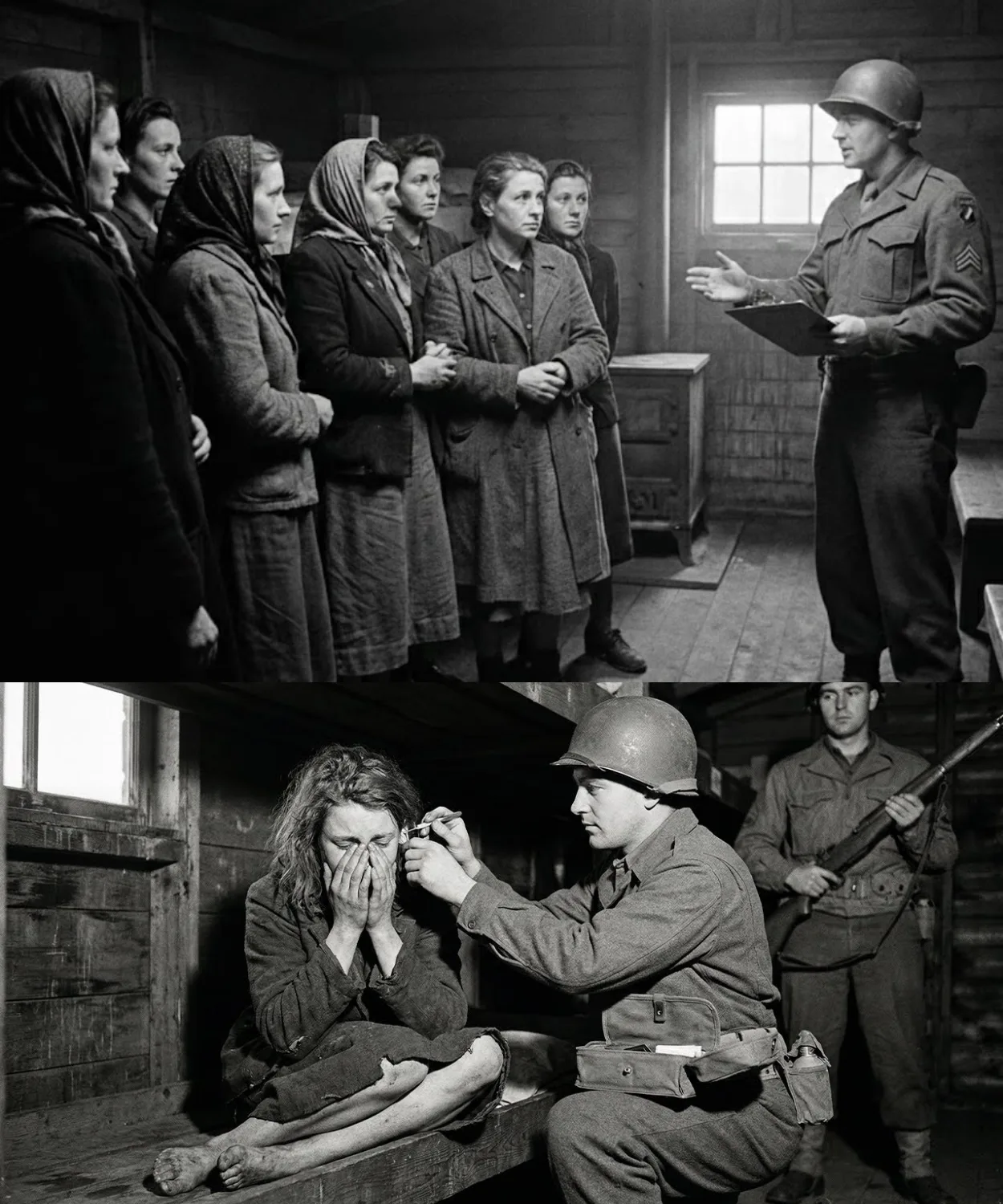

In the final weeks of the war, a group of German women, military auxiliaries, and civilian workers were transported to a temporary Allied holding camp in Western Europe.

They expected interrogation, accusations, harsh treatment.

Instead, the first American sergeant who entered the room said something no one was prepared for.

Show us your feet.

The room froze.

The women looked at one another, unsure they had understood correctly.

Some assumed it was a mistransation.

Others believed it was meant to humiliate them.

One woman instinctively stepped back, her hands clenched at her sides.

The interpreter hesitated before asking, “Why?” The American soldier did not smile.

He did not raise his voice.

He simply repeated calmly, “Shoes off.

Nothing else.” The tension only grew.

In the German system, appearance meant discipline.

to be ordered without explanation to remove their boots felt wrong, even threatening.

But refusing an Allied command could bring consequences.

Slowly, one by one, they removed their shoes.

Dust fell to the floor, the room filled with silence.

None of them understood what this moment meant, or that this strange request had nothing to do with punishment.

And then the Americans noticed something they had not expected.

The women waited in silence after removing their boots.

No insults followed.

No shouting, no punishment.

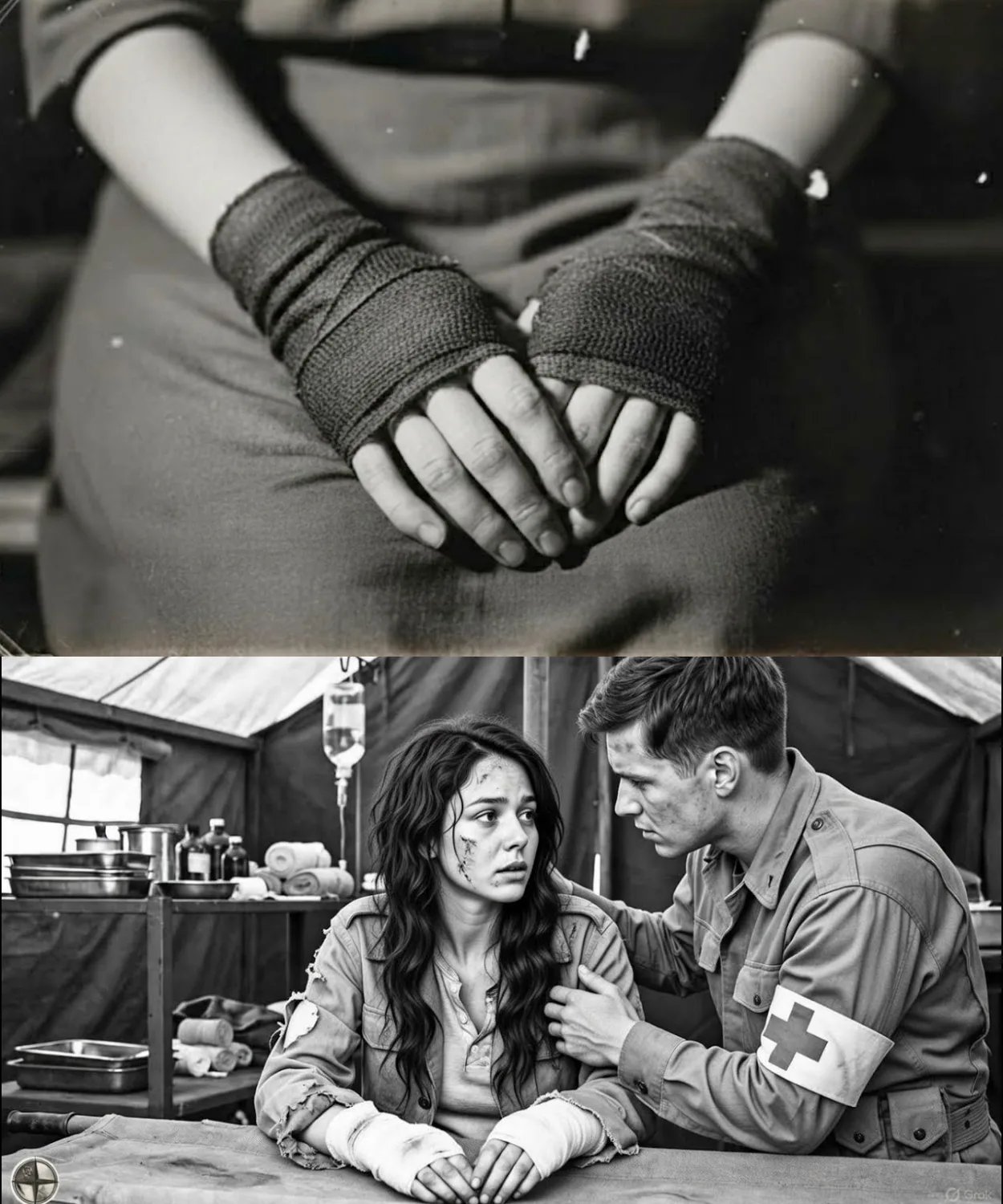

Instead, an American medic stepped forward.

He crouched down, not aggressively, not hurried, just focused.

One by one, he looked at their feet, ankles, and heels.

Some were swollen, others were bruised.

A few showed signs of untreated infections.

The women were confused.

This was not an interrogation.

This was an inspection.

During the final months of the war, Allied forces had learned something important.

Many prisoners, especially women, arrived in camps already injured or ill from forced marches, shortages, and months of neglect.

Feet told the truth.

Blisters meant long marches.

Cracked skin meant lack of supplies.

Severe swelling meant exhaustion or worse.

One American officer quietly spoke to the interpreter.

If they can’t walk, they don’t go to transport.

That single sentence changed everything.

Those with serious injuries were separated, not for punishment, but for medical care.

They were sent to rest areas instead of crowded transfers.

Some avoided days of harsh movement simply because someone had checked their condition early.

The women slowly realized something unsettling.

This strange request had not been about control.

It had been about logistics and survival.

For the first time since their capture, a few of them felt something unexpected.

Relief and confusion because this was not the enemy they had been warned about.

But not everyone passed the inspection.

And for those who did, a very different journey was waiting.

After the inspection ended, the women were told to stand.

No explanations, no speeches.

An American officer pointed calmly to the floor.

Two lines.

At first, no one moved.

Then the interpreter clarified.

Those who had been marked by the medic were to step to the left.

Everyone else remain on the right.

Boots scraped against the wooden boards.

A few women hesitated, unsure which side meant safety.

Friends who had arrived together now stood apart.

The left line was smaller.

Those women looked embarrassed, some limping slightly, others pale with exhaustion.

They assumed they had failed some test.

The right line was longer, stronger, silent.

The officer spoke again, his voice low and matterof fact.

Left line goes to medical holding.

Right line prepares for transport.

Only then did the meaning settle in.

Transport meant crowded trucks, long drives, temporary camps with little space and less patients.

Medical holding meant beds, treatment, time.

One woman in the right line stared at her friend on the left.

They locked eyes.

Neither smiled.

Neither waved.

That was the last time they saw each other.

As the groups were led out through separate doors, something unexpected happened.

A few of the women in medical holding began to cry, not from fear, but from release.

For weeks, they had prepared themselves for cruelty.

Instead, they were given something quieter, structure, procedure, and a reminder that survival sometimes depended on details as small as the condition of your feet.

But the war was not over for them yet, and the next place they were taken would challenge everything they thought they understood about captivity.

The medical holding area was nothing like the women had imagined a prison would be.

There were no raised voices, no threats, only order.

The building was an old schoolhouse converted into a temporary medical unit.

Windows were cracked open for air.

Thin blankets lay folded on ironframed beds.

An American nurse moved methodically from one patient to the next, writing notes without comment.

For the women in the left line, time slowed.

Their feet were cleaned, bandaged, treated with supplies they had not seen in months.

Some were told to rest for days.

Others were ordered to stay off their feet entirely.

No one asked about ideology.

No one asked about guilt, only conditions.

Across the yard, the women sent to transport experienced something very different.

They were loaded onto trucks before dawn, packed tightly, boots back on, rations minimal.

The journey was long and silent.

Each stop brought uncertainty.

New faces, new rules, new waiting.

Those in medical holding heard the engines leave.

And for the first time since capture, they understood how close they had come to a harder path.

At night, lying on thin mattresses, they whispered to one another.

Not about politics, not about the war, about small things, warm water, clean bandages, and the strange moment when everything had changed because someone had asked to see their feet.

But this separation would not last forever, and soon both groups would face the same question.

What happens after the war ends when captivity no longer has a clear purpose? Months later, the war was officially over.

The camps slowly emptied.

Names were checked, papers signed, gates opened.

The women who had once stood in two separate lines now left in different directions.

Some returning to damaged cities, others to villages that no longer felt like home.

There were no ceremonies, no apologies, no explanations, just release.

Years later, a few of them would speak about captivity, not with anger, but with confusion.

They remembered the fear of the unknown, the silence, the waiting, and they remembered one strange moment more clearly than any other.

Show us your feet.

At the time, it had sounded absurd, suspicious, almost insulting.

Only later did they understand what it meant.

It was not a test of obedience, not an act of humiliation, not a threat.

It was procedure, a small, practical decision made in a chaotic time.

One that quietly shaped who rested, who traveled, and who endured something harder.

History often focuses on battles, speeches, and flags.

But survival sometimes turned on details so small they were barely noticed.

A pair of worn boots, a swollen heel, a medic who chose to look, and a war remembered not only for its violence, but for moments when humanity appeared in the most unexpected form.