They thought America was weak.

They thought its soldiers were soft, its factories clumsy, its people too spoiled to fight a real war.

Captured German troops laughed at the very idea that the United States could stand against the mighty Vermacht.

But when they finally crossed the ocean and saw what awaited them, their laughter stopped.

This is the story of how German prisoners of war discovered the true face of America and why many of them never wanted to leave, mocking their capttors.

When the German soldiers were captured on the battlefields of Europe, whether in North Africa, in Italy, or after the storm of D-Day, they carried with them a deeply rooted belief.

America was weak.

Nazi propaganda had drilled it into their heads.

They were told the United States was nothing more than a patchwork of immigrants, soft factory workers, and spoiled youth who could never endure the brutality of war.

Compared to the hardened warriors of the Vermacht, Americans were supposed to be clumsy amateurs.

So when these men found themselves surrounded, forced to lay down their weapons, and marched into Allied custody, many of them still mocked the very idea that America could truly fight.

Their pride, bruised by capture, found comfort in ridicule.

They scoffed at their guards, muttering that the US was nothing without its machines.

That Americans couldn’t win a real fight without overwhelming numbers.

and endless supplies.

In their minds, they were still the elite.

On the transport ships bound for the United States, this arrogance spilled over into open laughter.

German officers and enlisted men alike shared jokes about what they would see once they arrived.

They imagined dirty, chaotic camps little more than wooden cages in the desert.

They expected cruelty, hunger, and humiliation.

Some even convinced themselves that America would simply execute them or work them to death in coal mines.

It was easier to believe in a nightmare than to accept the possibility that their enemy was stronger and more organized than they had been told.

For the prisoners, keeping up this mocking attitude wasn’t just pride.

It was survival.

To admit admiration for America, even in whispers, was dangerous.

Hardline Nazis kept watch over their fellow soldiers, ready to punish anyone who showed weakness.

So they made sure to laugh, to sneer, to call the Americans soft and unfit for war.

Their words were a shield protecting them from the fear of the unknown.

But beneath the surface, doubt lingered.

They had seen the endless columns of American tanks and trucks rolling through France.

They had felt the weight of the US Air Force’s bombing raids that shattered cities and supply lines with precision and relentlessness.

Even as they laughed, some wondered silently, “How could a weak nation produce so many planes, so many ships, so much firepower? Still, the bravado continued.

As the ships crossed the Atlantic, the Pu clung to their arrogance.

In their minds, America was a land of jazz music, corruption, and racial conflict, a place incapable of unity, incapable of sacrifice.

They mocked the guards as they stood watch, claiming that the only reason America was even in the war was money, not courage.

They thought they knew exactly what awaited them.

A poor, disorganized prison system run by men too inexperienced to handle real soldiers.

They believed they would endure it with ease, surviving on German discipline while their capttors fumbled.

What they did not know was that their world was about to be shaken to its core.

For as soon as they set foot on American soil, they would be confronted with something they had never imagined.

Not weakness, not cruelty, but a system of order, prosperity, and even humanity that would force them to rethink everything they thought they knew about their enemy.

Their mocking laughter would not last long, the long journey west.

The journey to America was unlike anything the German prisoners had imagined.

After capture, they were herded into makeshift holding camps in Europe, waiting for transport.

Barbed wire, armed guards, and long days of uncertainty stretched before them.

But then came the moment none of them expected orders to board massive Allied ships bound for the United States itself.

The Atlantic crossing was tense.

German hubot still prowled the waters, and the irony wasn’t lost on the captured submariners, who now sat helpless in the very cargo holds their comrades once hunted.

The prisoners were kept under strict watch, packed into tight quarters, guarded by American soldiers who rarely spoke to them.

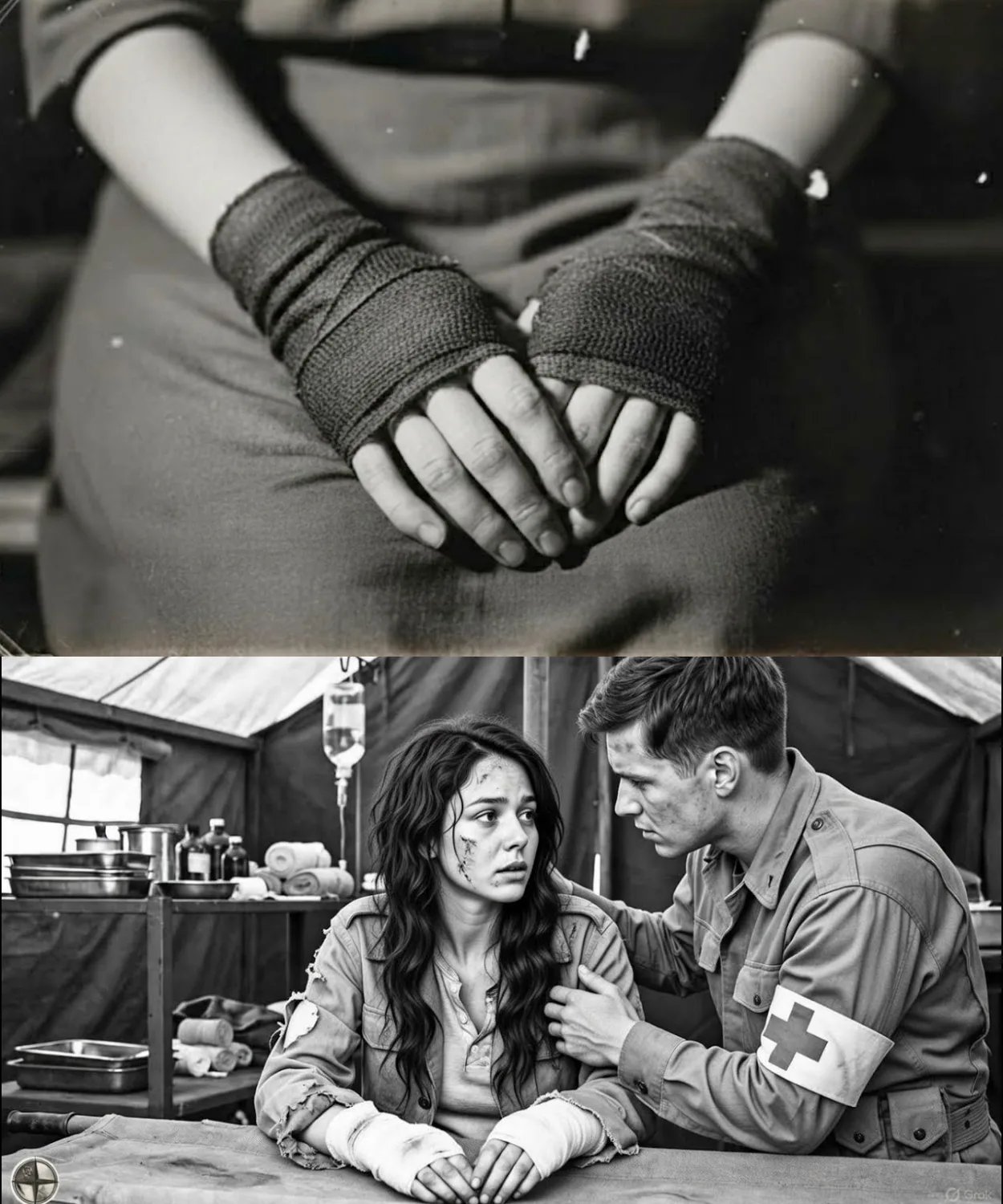

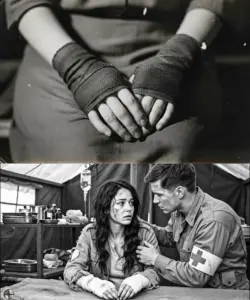

Yet, the conditions surprised them.

They were given blankets, warm meals, and even medical checks.

For men who had braced themselves for brutality, this was disarming.

Still, arrogance lingered.

On deck, some prisoners mocked their guards, whispering that America could only win by hiding behind oceans and numbers.

Others joked about being put to work in fields, chained like slaves.

But when the ships pulled into harbor, reality set in.

Towering cranes, endless rows of trucks, and sprawling factories lined the docks.

The scale of America’s industry was staggering.

This was not the weak, fractured nation they had been told about.

For the first time, doubt began to gnaw at their certainty.

First glimpse of America.

Disembarking from the ships, the prisoners expected jeering crowds or cruel treatment.

Instead, they found indifference.

Most Americans barely looked their way.

To a nation mobilized on such a massive scale, a few thousand German PS were little more than a footnote.

Trains awaited them.

Long, powerful locomotives stretching farther than most Germans had ever seen.

As the prisoners sat behind barred windows, they passed through landscapes that shocked them.

vast farmland, modern cities, highways packed with cars, and factories that seemed to run endlessly.

Everywhere they looked, they saw abundance and order.

The mocking tone among them grew quieter.

They had expected chaos, but instead they saw a nation humming with discipline and energy.

Some stared in silence, realizing that the propaganda fed to them in Germany had been a lie.

Others clung stubbornly to their pride, insisting it was all a facade.

But deep inside, the image of a poor, divided America was crumbling.

By the time the trains rolled into the camps, one thing was clear.

This enemy was not weak.

America’s strength was not just in its weapons.

It was in its sheer scale, its resources, and its ability to fight a war while still living in prosperity.

The prisoners had seen enough to know their war would not end the way they once believed.

Inside the camps, when the trains finally stopped, the prisoners braced for the worst.

They imagined barbed wire cages, starvation rations, and brutal guards.

Instead, they were marched into camps that looked nothing like the nightmares they had been promised.

The barracks were wooden, simple, but clean, with bunks, stoves, and even windows.

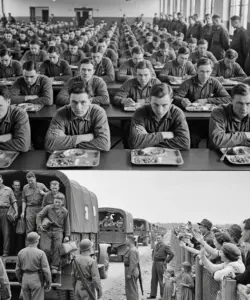

Meals shocked them most of all, bread, meat, vegetables, sometimes even coffee.

For men who had grown used to thin rations at the front, this was almost a luxury.

They joked bitterly among themselves that they were eating better in captivity than many of their families back in Germany.

Discipline inside the camps was firm but not cruel.

Guards watched every move, but they did not beat or torment the prisoners.

Rules were clear.

Follow orders, no trouble.

The Germans had expected hostility.

Yet most guards treated them with indifference.

just another duty in a nation already consumed by war.

The freedom was surprising, too.

Within the fences, prisoners moved about during the day, worked in kitchens or gardens, and even played soccer on open fields.

It was captivity, yes, but nothing like the violent punishment they had feared.

Slowly, the snears and laughter faded.

America’s strength was not only in its weapons and factories.

It was in its ability to hold enemies with confidence without cruelty and still maintain order.

A taste of culture.

As weeks turned into months, the camps revealed something even more unexpected.

Culture.

American authorities allowed libraries stocked with books, classrooms for language lessons, and even instruments for those who could play.

Soon, German orchestras formed inside the camps, performing concerts for fellow prisoners and sometimes even for curious American visitors.

Sports became a daily ritual.

Soccer fields echoed with shouts, while some learned baseball from the guards.

Theater groups sprang up German prisoners writing, directing, and acting in plays.

These weren’t distractions.

They were deliberate attempts by America to keep the men occupied, disciplined, and without realizing it, exposed to democratic values.

For many prisoners, this was the first time they experienced freedom of thought.

Inside Germany, Nazi ideology had been enforced at every level of life.

In these camps, men debated politics, philosophy, and music without fear.

Some clung to their old beliefs, but others began to question.

Could a nation truly be weak if it allowed its enemies to learn, create, and even thrive behind barbed wire? The laughter that once mocked America had been replaced with something new.

Curiosity.

and curiosity would soon grow into quiet admiration.

Friend or foe, life inside the camps wasn’t without conflict.

Among the prisoners, there was a sharp divide.

Hardcore Nazis still held influence, and they saw it as their duty to keep German pride unbroken.

They enforced discipline with threats, intimidation, and sometimes violence.

Anyone who showed admiration for America or even simply relaxed too much risked being labeled a traitor.

Fights broke out.

Some prisoners secretly wanted to learn English, to take part in classes or read American newspapers that occasionally reached the camps.

But others warned them it was dangerous to show interest in the enemy.

A few men who spoke too openly about their doubts found themselves targeted, beaten in the shadows of the barracks by fellow Germans still loyal to the Reich.

The American guards noticed this tension, but rarely intervened, at least not at first.

They let the Germans govern themselves inside the fences, a strategy that revealed much about the prisoners loyalties.

It became clear who was unshakably tied to the Nazi cause and who was beginning to see the world differently.

This divide grew sharper as months passed.

For some, captivity only deepened their hatred.

But for others, America’s calm strength and unexpected fairness planted seeds of doubt that no Nazi overseer could erase.

The camps had become more than prisons.

They were battlegrounds for the minds of the men inside.

Changing minds.

The longer the prisoners stayed, the more their perspective shifted.

At first, they mocked the guards for being soft.

But over time, they noticed something.

American discipline didn’t need constant fear to survive.

The guards weren’t brutal, yet the system worked.

Rules were followed, order was kept, and life moved forward with surprising ease.

Small experiences made deep impressions.

A guard sharing a cigarette.

A farmer in town thanking German laborers for their work instead of spitting at them.

The simple fact that food was plentiful, even for enemies, was enough to shatter old propaganda about America as a corrupt, starving society.

Letters from home painted a stark contrast.

Families in Germany wrote of shortages, bombings, and endless suffering.

Meanwhile, the prisoners ate full meals and played soccer on green fields.

Slowly, admiration replaced mockery.

Some admitted privately that they hoped to stay in America after the war.

Others began to imagine what Germany might look like if it followed a system less built on fear and more on opportunity.

For many, it was the first time they truly doubted the world the Nazis had promised them.

America hadn’t broken them with cruelty.

It had changed them with strength, abundance, and a strange kind of humanity.

The aftermath.

When the war finally ended in Europe, the German prisoners faced a choice.

For decades, they had been told that America was weak, corrupt, and doomed to fail.

Now, many of them knew the truth.

It was a nation of order, abundance, and quiet strength.

The world they had mocked was real, and it had shaped them in ways they could never have imagined.

Some returned to Germany, carrying stories of the strange kindness and efficiency of their former captives.

They spoke in hushed tones about clean barracks, plentiful meals, libraries, and orchestras, a world far removed from the destruction they had left behind.

Many confessed that their view of America had shifted completely.

The fear and arrogance they had held at capture had been replaced with respect, even admiration.

Yet, not all went back.

A surprising number of PSWs chose to stay in the United States, drawn by the prosperity and freedom they had witnessed firsthand.

Former soldiers who had laughed at the idea of American strength now built lives on the very soil they had once been trained to see as an enemy.

Some became farmers, others craftsmen, and a few even joined the military or industrial workforce, contributing to the same nation they had once scorned.

The camps had done more than hold prisoners they had transformed them.

Through unexpected generosity, fairness, and exposure to a thriving society, the Americans had turned fear and hatred into understanding.

For the men who remained in the US, the war’s end was not just the end of conflict, but the beginning of a new life one built not on propaganda, pride, or ideology, but on opportunity, order, and respect.

And in the quiet moments when they reflected on the journey from mockery to admiration, they understood the unspoken lesson.

True strength does not always roar.

Sometimes it simply endures and quietly changes the hearts of even the most hardened enemies.