Texas, 1943.

The train rattled through endless prairie, carrying human cargo across a landscape so vast it swallowed fear.

Inside the converted freight cars, 17 German women pressed their faces to the narrow windows, watching America unfold like a fever dream.

They had expected darkness.

Instead, the sun blazed with an intensity that made their eyes water, transforming the horizon into liquid gold.

Lisa Hartman gripped the wooden bench beneath her, feeling every jolt through her spine.

The air inside smelled of sweat and metal, and something else possibility, perhaps, or simply exhaustion.

To the gaps in the planks, she could see cattle moving like distant shadows across fields that stretched beyond comprehension.

In Hamburg, her entire neighborhood could fit inside one of these ranches.

Here, space itself seemed weaponized, a reminder of how small they had become.

The capture had come 4 months earlier off the coast of Portugal.

The ship had been bound for Argentina, carrying women whose husbands served in German intelligence operations across South America.

British destroyers appeared at dawn, cutting through fog like knives through silk.

Lisa remembered the moment the engines stopped, how silence became heavier than sound.

She had been carrying forged papers identifying her as a Swedish teacher.

No one believed them.

Now the train slowed, breaks screaming against steel.

Through the window, Lisa saw it.

Camp Hearn rising from the Texas dust like something conjured from contradiction.

Wooden guard towers pierced the sky, but between them stretched corral where horses moved with liquid grace.

Barbed wire gleamed in the afternoon light.

Yet beyond the fences, she could see children playing near a farmhouse.

Their laughter carried on wind that smelled of hay and possibility.

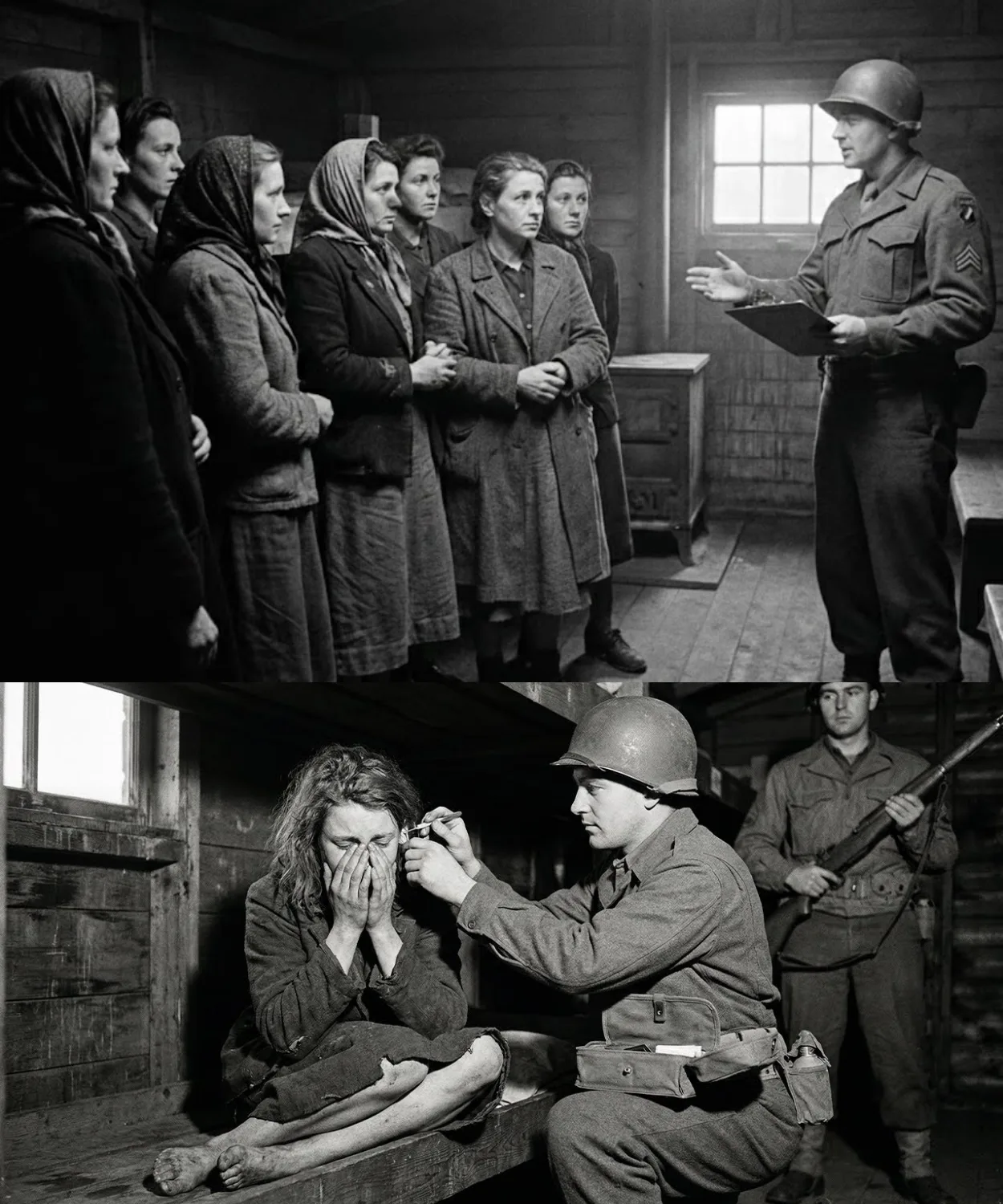

The doors opened.

Heat rushed in like a physical presence, pressing against skin, stealing breath.

A guard stood at the opening, silhouetted against impossible brightness.

Lisa’s hands trembled as she stood, preparing for orders, barked in the harsh tones she had learned to expect.

Instead, the man simply stepped aside, gesturing toward the platform with something almost resembling courtesy.

“Welcome to Texas, ladies,” he said, his accent thick as honey, strange as moonlight.

“I’m Sergeant Miller.

You folks will be helping out here, feeding, cleaning, riding, if you’re up for it.

Riding.

The word hung in the air like something from another life.

Another [snorts] universe where women prisoners mounted horses instead of marching to interrogation rooms.

Lisa exchanged glances with Emma Schneider, a Berlin opera singer whose hands still moved as if conducting invisible orchestras.

Neither spoke.

speaking felt dangerous when reality refused to align with everything they had been taught about American captives.

They were led toward a cluster of low buildings past corral where ranch hands worked with horses, their movements efficient and unguarded.

The prisoners walked in silence, boots crunching against gravel, each step taking them deeper into territory that resembled nothing from the propaganda films they had watched in church basement and community halls.

Those films had shown American camps as places of cruelty refined into bureaucracy, where prisoners existed as numbers rather than names.

Here, someone had planted flowers near the mess hall, entrance patunias blooming in defiance of the heat.

Their purple faces turned toward an indifferent sun.

The barracks smelled of fresh wood and laundry soap.

20 beds lined the walls, each made with precision that would satisfy any military inspection.

On every pillow lay a folded towel and a bar of soap that smelled like lavender.

Lisa lifted hers to her face, breathing in something she had not experienced in months.

Gentleness.

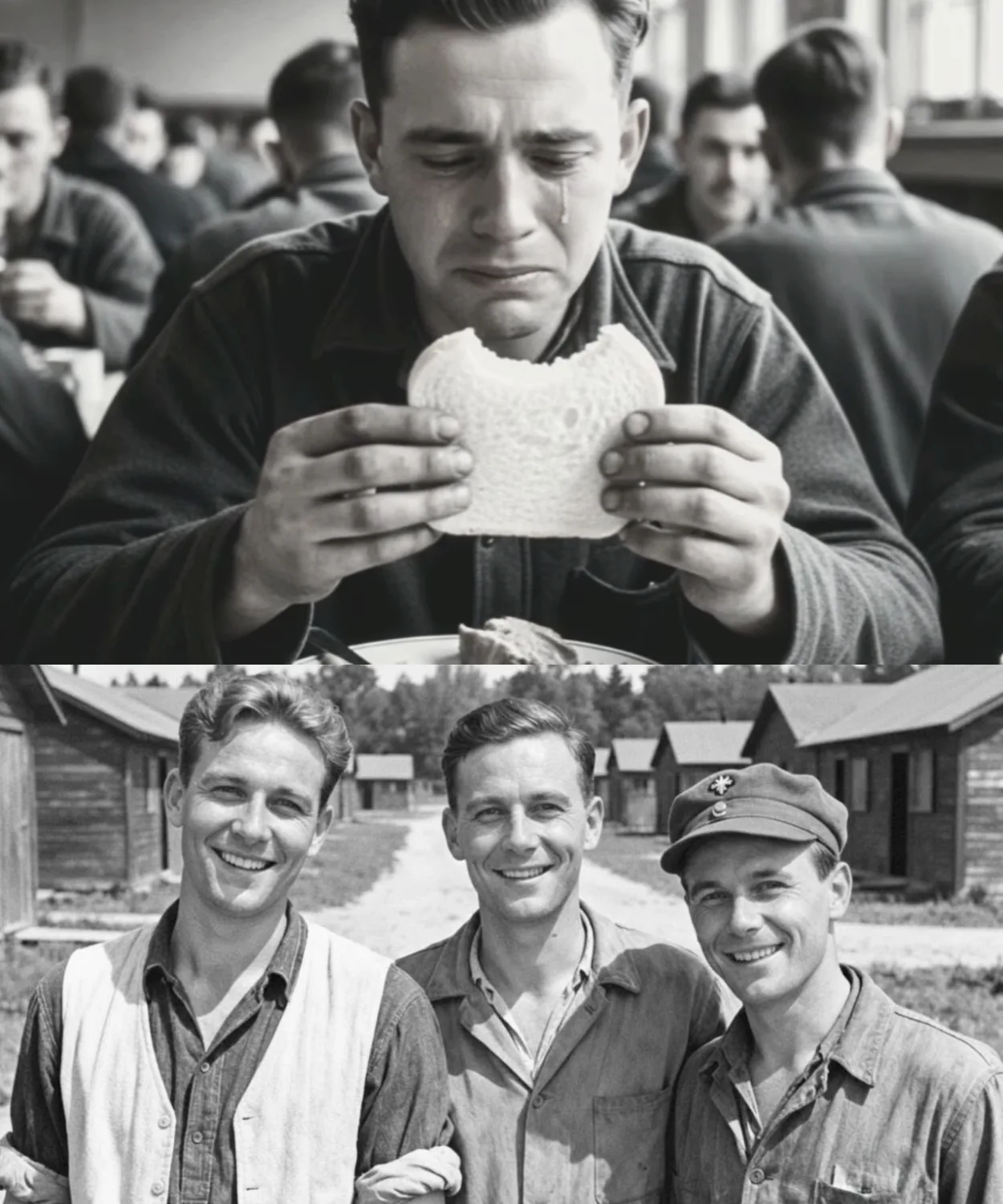

That evening, they were led to the messaul.

The smell hit first bacon frying, bread baking, coffee brewing in quantities that seemed obscene.

In Hamburg, during the final months before her capture, Lisa had survived on Zotat’s coffee made from acorns and bread mixed with sawdust.

Here, the kitchen staff German men who had been captured earlier in the war moved between stoves with expressions of men who had found something unexpected.

Comfort in captivity.

Sergeant Miller stood near the serving line, watching as the women filed past, their eyes widening at portions that exceeded anything they had seen in years.

Steak, fried potatoes, green beans glistening with butter, and bread so white it looked like something from a child’s story book.

Plenty more where that came from, Miller said, nodding toward the kitchen.

Ain’t no use being hungry here.

You work hard, you eat well.

That’s how we do things.

Lisa sat at a long table, staring at her plate.

Beside her, Emma whispered in German.

It’s a test.

They’re measuring our gratitude before they take it away.

But the food remained.

And when Lisa finally lifted her fork, the taste of real butter nearly brought tears that had nothing to do with onions or smoke.

Around the room, other women ate with mechanical efficiency, as if speed could prevent this moment from being revoked.

Only gradually did the pace slow did shoulders begin to drop from their defensive positions near ears.

After dinner, they were given an hour of free time before lights out.

Lisa walked toward the perimeter fence, drawn by the vastness beyond it.

The sun was setting, painting the sky in colors.

She had no names for oranges that bled into purples, reds that softened into pinks.

In Germany, even the sky had seemed rationed during wartime, compressed between buildings into narrow channels of gray.

Here, the horizon swallowed everything, including the certainty she had carried about who her enemies were.

A voice spoke from behind her.

First time in Texas.

She turned to find Sergeant Miller standing several feet away, hands in pockets, posture relaxed in a way that suggested genuine curiosity rather than interrogation.

Lisa nodded, not trusting her English beyond simple gestures.

It’s something, isn’t it? He looked toward the sunset, squinting slightly.

My grandfather came here from Kentucky in 1880.

Said it was the only place big enough for his thoughts.

I didn’t understand what he meant until I tried living in Dallas for a year.

He paused, then added, “You speak English some?” Lisa managed, her accent thick, each word feeling like something pulled from deep water.

“I study before.” That’s good.

You’ll pick it up quick here.

We got German speakers, English speakers, and plenty of folks who just grunt and point.

His smile carried no malice, no triumph.

you’ll fit right in.

He walked away then, leaving Lisa alone with the darkening sky and a confusion that felt almost worse than fear.

Fear, she understood.

Fear [snorts] made sense in the architecture of war, fit neatly into the narratives she had been fed about American cruelty and European superiority.

But kindness, casual kindness from a guard toward a prisoner, offered with the same ease one might extend toward a neighbor, that required reconstruction of everything she thought she knew.

That night, lying in darkness, while other women whispered in German about strategies for survival, Lisa remembered a phrase her grandmother had used when Lisa was a child.

The truth is whatever breaks your heart.

She had never understood it until now.

until she felt something inside her chest crack open like earth after a long drought, making space for water she had not known she needed.

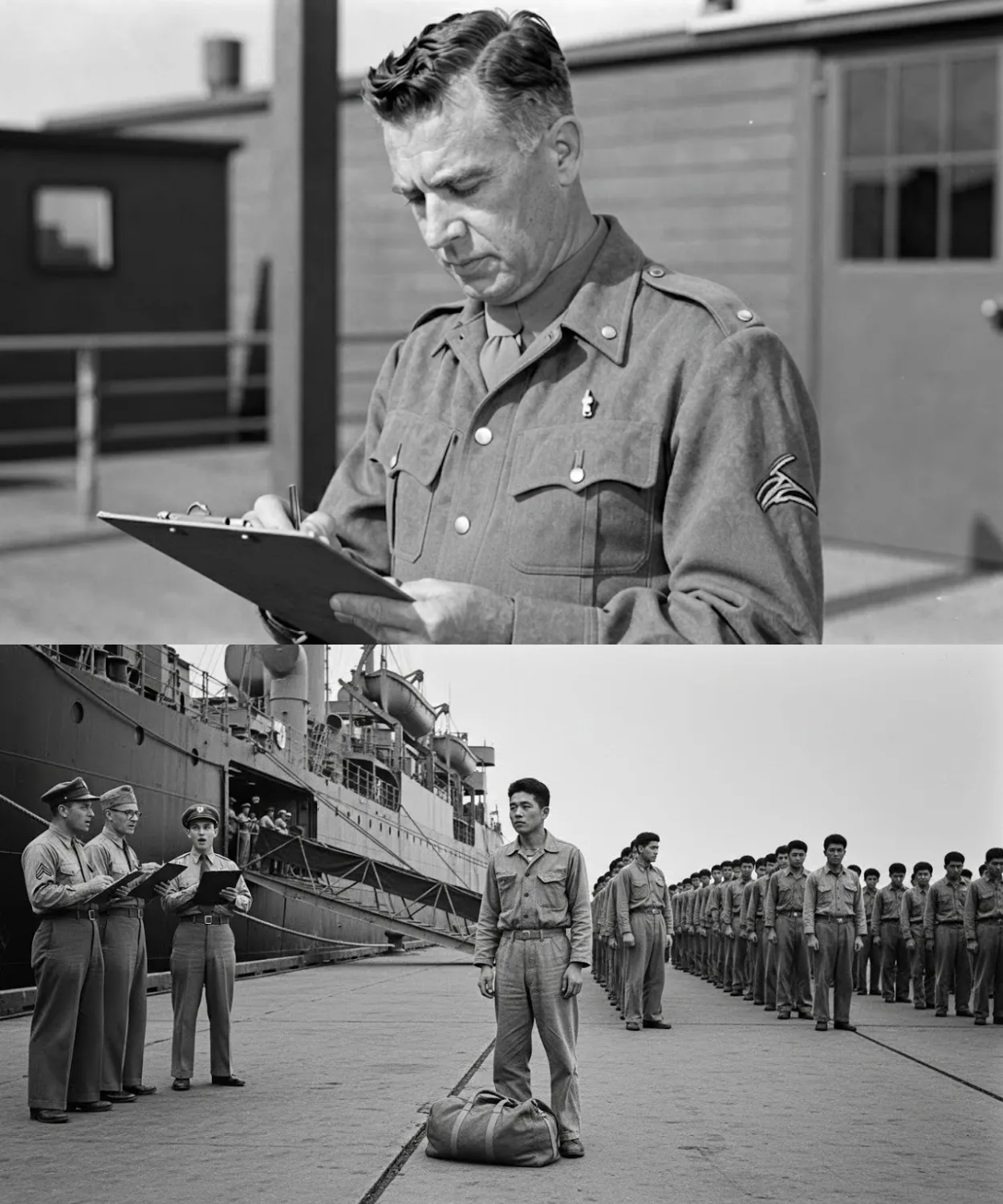

The work began the next morning.

Dawn came early in Texas, announced by roosters and the low calls of cattle in distant pastures.

The women were divided into groups, some assigned to kitchen duty, others to laundry, others still to maintenance of the campgrounds.

Lisa found herself in the stables alongside Emma and three other women whose names she was still learning to pronounce correctly.

The stable manager was a man named Curtis, whose weathered face suggested decades spent under open sky.

He moved between horses with the confidence of someone who had forgotten that communication could be difficult, who simply expected to be understood and was therefore understood.

He demonstrated how to brush down the horses, how to check their hooves for stones, how to speak to them in low tones that soothed rather than commanded.

“Horses know fear,” he said, running his hand along Amari’s flank.

They can smell it, tasted in the air.

“You come at them nervous, they get nervous.

You come at them calm, they stay calm.

It’s that simple and that complicated.” Lisa took the brush he offered, approaching a gray geling, who watched her with eyes that seemed to hold ancient knowledge.

She had ridden as a girl before the war, before everything became about survival and strategy.

The brush moved through the horse’s coat, revealing muscles that rippled beneath her touch.

Life humming with a rhythm that had nothing to do with human conflict.

“That’s Dusty,” Curtis said, leaning against a stall door.

He’s older than sin and twice as patient.

Good horse for learning on.

The hours passed in a rhythm defined by physical labor rather than intellectual anxiety.

Mcking stalls, hauling water, spreading fresh hay each task demanded presence in the body rather than the mind.

By noon, when they broke for lunch, Lisa’s hands achd in ways she had almost forgotten were possible, ways that suggested purpose rather than simply endurance.

The messaul offered sandwiches thick with roast beef, potato salad, creamy with mayonnaise and iced tea so cold it made her teeth hurt.

Lisa sat with Emma, both women eating in silence that felt less strained than contive.

They’re trying to make us forget, Emma said finally, her voice low.

Make us soft so we can’t resist.

Lisa considered this, watching through the window as guards played cards at a nearby table.

Their laughter genuine and unforced “Resist what?” she asked.

“We’re already captured.

There’s nowhere to escape to.

No mission to protect.

Then they’re trying to make us grateful,” Emma insisted.

“Make us complicit in our own imprisonment.

But gratitude, Lisa was learning, didn’t require complicity.

One could be grateful for bread without endorsing the system that withheld bread elsewhere.

One could acknowledge kindness without forgetting cruelty.

The human heart, it seemed, was large enough to hold contradictions that would tear apart any propaganda film’s neat narrative.

At afternoon, Sergeant Miller appeared at the stables.

“Miss Hartman,” he said, pronouncing her name with careful attention to the German sounds.

“You ride before?” Lisa nodded, setting down her pitchfork.

Yes.

Long time, but yes.

Curtis tells me you got a good hand with horses.

We’re moving some stock to the south pasture this afternoon.

Could use an extra rider if you’re interested.

The invitation hung between them like something fragile, something that could shatter under the weight of wrong interpretation.

Lisa looked at Emma, who stared back with expression that mixed warning and curiosity.

I Lisa started then stopped realizing she had no vocabulary for this situation in any language.

Finally, in German, she said to Emma, “What do I have to lose?” Emma’s smile was thin as wire.

Only whatever dignity we have left if this is a trap.

But Lisa followed Sergeant Miller to the corral, where Dusty stood saddled and waiting, his patient eyes reflecting afternoon sun like coins at the bottom of a well.

Miller helped her out, not touching her unnecessarily, not making assumptions about her ability, simply offering a hand that she could refuse or accept.

She accepted.

The leather felt familiar beneath her, the horse’s warmth rising through her legs, the rains alive in her hands with Dusty’s breathing and heartbeat.

Miller mounted his own horse, a paint marray, whose coat looked like clouds at sunset, and guided them toward the south gate.

“Stay close at first,” he said as they rode through.

The terrain’s trickier than it looks.

They moved across land that seemed to have no relationship with maps or borders, where the only boundaries were drawn by fence lines that stretched toward vanishing points.

The sun pressed down with an insistence that felt personal, transforming sweat into something sacred, proof of existence in a landscape that made humans feel provisional.

Cattle moved in loose groupings, their paths defined by instinct rather than orders.

Miller worked the herd with subtle movements, never raising his voice, trusting the horse and the cattle to understand intentions communicated through pressure and release.

Lisa followed his example, feeling muscle memory waken her body, reminding her of summers before the war when riding meant freedom rather than labor.

“You’re good at this,” Miller said after they had moved 20 head toward the southern water tank.

Real natural.

My father, Lisa said, the words coming easier now.

He have had horses for business, for family.

What kind of business? Transport before everything.

[clears throat] Miller nodded, not pressing for details that might force her into territories mind with loss.

They rode in silence for a while.

the only sounds the creek of leather and the low calls of cattle content in their ignorance of human war.

Finally, as they turned back toward the camp, Miller spoke again.

I know this must be strange for you, he said.

Being here being treated like well, like people.

I imagine you were told different stories about Americans.

Lisa felt something catch in her throat.

Yes, she managed.

Many stories.

Were they true? The question required honesty.

She wasn’t certain she could afford.

But something about the empty horizon, the patient horse beneath her, the guard who rode alongside rather than behind her.

Something about all of it demanded truth.

Some true maybe some not.

I don’t.

She struggled for words then switched to German hoping he might understand tone if not content.

Each weighs Nick Mayor was varist.

Diwirite is composer as manons had I don’t know what’s true anymore the truth is more complicated than we were told Miller was quiet for a long moment then in German it surprised her with its clarity he replied dwarheight is immmer complant sitch cu suchin the truth is always complicated that’s why it’s worth seeking they returned to the stables as the sun began its descent painting everything in shades of amber and gold.

Lisa dismounted, her legs trembling slightly from effort and emotion nixed in proportions she couldn’t measure.

Miller took Dusty’s reigns, meeting her eyes with expression that held no triumph, no judgment only acknowledgment of something passed between them that had nothing to do with war and everything to do with humanity stubborn persistence.

“Same time tomorrow?” he asked.

If you’re interested,” Lisa nodded, not trusting her voice.

That evening, she sat on her bunk while other women prepared for sleep, their conversations flowing around her like water around stone.

“Emma sat down beside her, smelling of laundry soap and exhaustion.

And you were gone a long time,” Emma said.

We moved cattle to the south pasture, and Lisa met her friend’s eyes, and I remembered what it felt like to be human instead of useful.

Emma absorbed this, her opera singer’s face showing the same attention to nuance she once gave to Puchini scores.

That’s dangerous, she said finally.

Remembering what we were, it makes this harder to endure or easier, Lisa countered.

Maybe remembering is how we endure.

The weeks that followed established rhythms that felt less like imprisonment and more like some strange form of displacement as if they had been transported not across ocean but across dimensions into a world where the rules governing prisoner and guard had been rewritten by hands that understood mercy as strategy more effective than cruelty.

Lisa rode with Sergeant Miller.

She learned his first name was James, though she never used it three times a week.

They moved cattle, repaired fence lines, checked water tanks and pastures so remote they seemed to exist outside time.

Their conversations grew less halting, her English improving through necessity, and his patience.

He told her about growing up in a small town where everyone knew everyone’s business, about losing his brother at Guadal Canal, about the strange guilt of serving in a prisoner camp while other men died in foxholes.

She told him about Hamburg, about the bombing raids that transformed night into perpetual noon, about her husband who had disappeared into the Eastern Front and never emerged.

She told him about teaching piano to children who no longer had pianos, about everything Coffee, Red Hope.

The propaganda, she said one afternoon while they rested the horses near a windmill whose blades turned with hypnotic persistence.

It told us Americans were barbarians, that you had no culture, no refinement, that you would treat prisoners like animals.

James laughed, but the sound carried no mockery.

And what did we tell ourselves about Germans? That you were all fanatics who ate babies for breakfast and worshiped a madman like he was God himself.

He shook his head.

Funny how both sides need the other to be monsters.

Makes the killing easier to justify.

But you don’t treat us like enemies, Lisa said.

Why? He considered this watching the windmills shadow stretch across earth baked hard as ceramic.

because you’re not my enemies.

You’re just people who got caught up in the same nightmare as me, only from a different angle.

He turned to look at her, his eyes serious beneath the hatbrim.

Besides, treating people decent isn’t about them.

It is about who I want to be when all this is over, and I have to look at myself in the mirror.

By midsummer, the transformation was undeniable.

The women who had arrived expecting cruelty had instead found something more disturbing.

Normaly.

They worked alongside German men captured at Kazarine Pass and Anzio alongside American guards who treated them with casual respect.

Alongside Mexican ranch hands whose families had worked this land before Texas was Texas.

They celebrated birthdays with cakes baked in the camp kitchen.

attended church services led by a chaplain who spoke about forgiveness in tones that suggested he actually believed it possible.

Lisa began teaching English to some of the women who struggled with the language using a worn dictionary someone found in the camp library.

Emma organized a choir that sang German folk songs on Sunday evenings, their voices rising into the vast Texas sky like prayers directed at stars instead of saints.

The opera singer’s hands stopped conducting invisible orchestras and started leading real ones, transforming women trained for domestic efficiency into something resembling an ensemble.

But underneath the routine, Lisa felt herself changing in ways that frightened her more than any interrogation could have.

She was beginning to forget how to hate.

the careful architecture of resentment she had built during the war years against Americans for their naive optimism against allies for their bombing campaigns, against the world for its refusal to align with their understanding of justice all of it was crumbling under the relentless assault of daily kindness.

One evening in late July, as the heat finally began to release its grip and allow temperatures to drop below scorching, James found her near the corral.

The horses stood in darkness like sculptures carved from shadow, their breathing a counterpoint to cricket song.

“Walk with me?” he asked.

They moved beyond the perimeter lights with a prairie stretched dark and infinite where stars crowded the sky in numbers that made her dizzy with perspective.

Their footsteps crunched against gravel and whispered through grass, then fell silent as they simply stood.

Two figures dwarfed by geography and circumstance.

I need to tell you something, James said finally, his voice careful, measured.

We’re being transferred different camp up north.

Prisoner swap got arranged with some higher-ups who need to make space for new arrivals.

Lisa felt the earth shift beneath her feet, though nothing moved.

when week from Thursday.

A week 7 days to prepare for departure from a place she had never intended to stay.

Had never wanted to call anything resembling home.

The irony felt sharp enough to draw blood.

Where? She asked.

Can’t say exactly.

Somewhere in Illinois, I think.

Colder than here, that’s for sure.

They stood in silence while the stars wheeled overhead in their ancient patterns, indifferent to human drama.

Finally, Lisa spoke in German, not caring whether he understood the words so much as the truth behind him.

Duhast Mitch Garrett on Zu Wissen Nick von Gangen Sand von Demanges in Minum and Cop You saved me without knowing it not from captivity but from the prison inside my own head.

James was quiet for a long moment.

Then in English he replied, “I think you saved yourself.

I just didn’t get in the way.

She turned to look at him.

this man who had shown her that enemies could be wrong about each other, that propaganda could fail against the simple weight of daily kindness, that hatred required maintenance, while compassion needed only permission to exist.

“I want to ask you something,” she said, her accent thick but words clear.

“And I need you to answer with truth.” “All right.

If we meet after the war in Germany or America, would you?” She paused, searching for vocabulary adequate to the moment.

Would you greet me as friend or as enemy? James smiled, and in the starlight she could see the warmth in his expression, the absolute absence of hesitation.

Lisa, I greet you as someone who helped me remember why we’re fighting this war.

Not for territory or revenge, but for the possibility that people from different places can sit under the same sky and see the same stars and recognize each other as human.

The transfer day arrived wrapped in heat that made the horizon shimmer like water, transforming distance into something liquid and uncertain.

The women gathered near the train that would carry them north, their belongings packed in bags that weighed more with memory than material.

The German men who had become their colleagues and sometimes friends stood nearby, offering awkward farewells in the universal language of regret for endings.

James approached Lisa as she waited to board, his hat in hands, expression caught between military professionalism and something more complicated.

Got something for you, he said, pulling a small leatherbound book from his pocket.

It’s a journal.

Figured you might want to write things down.

Help you remember or forget depending on what you need.

Lisa took it, feeling the supple leather, the cream pages rough against her fingers.

Thank you, she managed the words inadequate containers for everything she felt.

for this for everything.

You ever make it back to Hamburg? James said, you look me up.

James Miller, New Bronfells, Texas.

That’s where my folks live.

We’ll have coffee and talk about horses and pretend the world makes sense.

She nodded, not trusting herself to speak further.

Then, before she could second-guess the impulse, she reached out and took his hand, shaking it with the firmness her father had taught her, grip firm, eyes direct, honor acknowledged.

“Please,” she whispered in English, the word carrying weight beyond its simple meaning.

“Please remember this.” And we were not monsters.

James met her eyes, and in his gaze she saw something that would sustain her through whatever came next recognition.

complete and unconditional.

“Never thought you were,” he said.

“Not for a second,” the train whistle screamed, cutting through the morning heat like a knife through silk.

Lisa boarded, finding a seat near the window, pressing her face to the glass as the locomotive lurched into motion.

Through the distortion of speed and tears, she watched Camp Hearn recede.

the corrals, the barracks, the mess.

Hall with its inongruous patunias, and the figure of a guard who had shown her that the opposite of enemy was not friend, but simply human, that cruelty was a choice rather than an inevitability, that kindness could be as a radical as any revolution.

That evening, as the train carried them through landscapes that shifted from desert to grassland to something approaching forest, Lisa opened the journal James had given her.

On the first page, she wrote in careful English, “Today I left a prison that taught me freedom.

I met my enemy and found my friend.

The war will end, but this will remain.” the knowledge that hatred is a story we tell ourselves, and stories can be rewritten if we have courage enough to pick up the pen.

” She closed the book, holding it against her chest like something sacred, and watched through the window as America unfolded in all its complicated, contradictory vastness, a country that had captured her body while somehow impossibly liberating her soul.

Months later, in a camp outside Chicago, where snow fell like feathers and the guards were less kind but still professional, Lisa received a letter.

The envelope or no return address, but she recognized the careful handwriting that had signed her transfer papers.

Inside a single photograph, Dusty the horse, standing in morning light, with patient eyes reflecting sun like promises kept.

on the back written in pencil.

Still here, still waiting for that coffee.

Jun Lisa kept the photograph in the journal pressed between pages where she had written about heat and horizons and the slow revolution that happens when propaganda meets reality and reality wins.

She kept it through the end of the war, through her eventual repatriation to a Germany transformed beyond recognition, through years of rebuilding and remembering and trying to explain to people who hadn’t lived it what it meant to be saved by an enemy.

In 1949, she made her way to New Bronfells, Texas.

carrying a worn leather journal and a photograph of a patient horse.

She found James Miller working at his family’s hardware store, older but recognizable, his eyes still holding that quality of attention that suggested he heard more than words.

“Coffee?” he asked when he saw her, as if four years and an ocean were nothing more than minor inconveniences.

Please, she replied, the word carrying everything it had carried that morning at Camp Hearn.

Gratitude, recognition, the acknowledgement that they had both survived, not just war, but the harder challenge of maintaining humanity within it.

They sat in a diner that smelled of hamburgers and possibility, talking about horses and weather, and carefully avoiding topics that still felt too raw for casual conversation.

But underneath the small talk, they both understood what the other represented.

Proof that the stories we tell ourselves about enemies can be wrong.

That kindness is not weakness.

That the hardest battles are fought not with weapons, but with the daily choice to recognize shared humanity, despite everything that insists we should not.

Outside the diner window, Texas stretched toward horizons that suggested infinite possibility.

Inside, two former enemies drank coffee and discovered they had become something more valuable than friends.

Witnesses to each other as humanity, living testimony that the worst of times cannot entirely extinguish the best of what people can be when given the chance.

The war had ended.

The remembering had just begun.

And in the space between enemy and friend, prisoner and guard, German and American, they had found something propaganda could never touch.

The simple, radical, revolutionary act of seeing another person clearly, and choosing compassion over hate.

In her journal that evening, Lisa wrote one final entry about Camp Herm.

I whispered, “Please,” and meant acknowledge that I am human.

He replied, “Not with words, but with actions sustained across months, with patience, with respect, with the careful preservation of my dignity, even when he had power to destroy it.

” His reply left me speechless, not because it was dramatic, but because it was consistent.

He showed me that the most powerful weapon against hatred is not love, but simple, persistent, ordinary kindness.

And that is how my enemy saved my soul.

by refusing to be my enemy one day at a time until the lie of our separation could no longer sustain itself.

She closed the journal looking out at the Texas night where stars hung low enough to touch and understood that some prisoners are freed by escaping their capttors while others are freed by discovering their capttors were never truly their enemies at all.

The walls had been real.

The bars had been steel.

But the most important liberation had happened inside her mind, where James Miller’s quiet rebellion against hatred had demolished the propaganda that insisted cruelty was the only possible response to war.

The cattle moved in distant pastures, restless in the heat.

The horses stood patient in their corrals.

And somewhere in the vast American night, two people who should have been enemies, proved that the human capacity for connection could survive anything, even war, even propaganda, even the carefully constructed lies we tell ourselves to make violence bearable.

Years later, when historians would examine the prisoner of war camps scattered across America during World War II, they would note with clinical precision the statistics.

How many prisoners, how many guards, how many incidents of escape or rebellion.

But numbers could never capture what really happened in places like Camp Hearn.

A slow dissolution of hatred in the face of daily kindness.

The impossible mathematics of enemy becoming human becoming friend.

Lisa Hartman lived to see the Berlin Wall fall, lived to see Germany reunited, lived to see the wounds of war slowly scar over, if never entirely heal.

But until her death in 1994, she kept that worn leather journal that photograph of a patient horse and the memory of a Texas summer when an American guard showed her that the most radical act of resistance against war is refusing to let it poison your capacity for compassion.

His reply had left her speechless then, but in the years that followed, she found her voice telling anyone who would listen that enemies are made through stories, and stories can be unmade by people brave enough to choose kindness when cruelty would be easier expected, even justified.

The war had tried to make them monsters to each other.

They had chosen daily and deliberately to be human instead.

And that choice, more than any battle or treaty, was what truly defeated the machinery of hate.