“Remove Your Coats.

Now.” — The Order That Left German Women POWs Frozen in Shock

A true story of terror.

True.

[groaning] Truth in Texas, 1945.

Three words in English.

That’s all it took to make 600 German women believe their worst nightmare was about to come true.

Open your coat.

But what happened next would shatter everything Nazi propaganda had taught them about Americans.

This is the true story of the most terrifying medical inspection in World War II history and why it changed everything.

Fort Hood, Texas, April 1945.

Dawn breaking over dust and barbed wire.

600 women stood in uneven rows on bare dirt, their breath visible in the cool morning air.

They wore whatever clothing they had left after 3 weeks of captivity.

Some still had their grave wear mocked auxiliary uniforms worn thin and stained.

Others wore cotton dresses issued by the American sizes never quite right.

Their faces were pale drawn, afraid.

They had survived bombs falling from the sky.

They had survived watching their cities burn.

They had survived being captured by enemy soldiers and transported across an ocean to a foreign land.

But now an American officer walked slowly down the line clipboard in hand.

And the women believed they had survived only to face something worse.

The contrast was stark.

These were German women standing in the heart of Texas as far from home as the earth allowed.

Behind them, canvas barracks flapped in the wind.

Around them, barbed wire gleamed in the rising sun.

In the distance, cattle loaded from nearby ranches.

Guards stood at regular intervals, rifles slung over shoulders, bottles of Coca-Cola in their hands.

The scene made no sense to European eyes.

This casualness, this abundance, this strange mix of military precision and cowboy.

It felt like a dream or the moment before a nightmare begins.

By the end of this story, these same women would be crying, but not from fear.

from something they never thought they’d feel toward American soldiers.

But first, let me take you back 3 weeks to when this journey began.

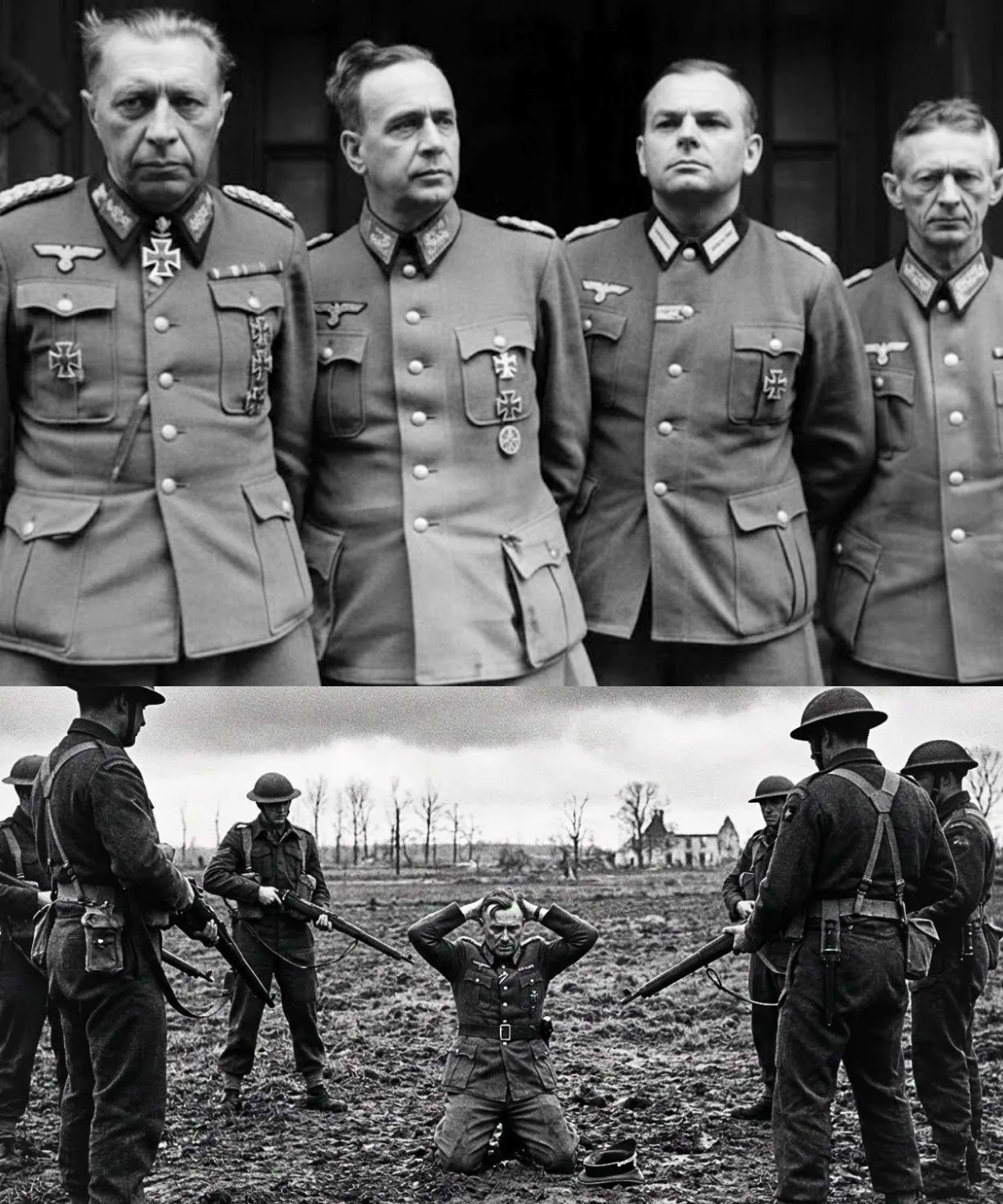

March 1945, Germany was collapsing.

The Vermach, once the most powerful military machine in the world, was breaking apart like ice in spring.

In the chaos of retreat, entire auxiliary units found themselves cut off from command from supply lines from any hope of escape.

Among these units were 600 women.

They were not soldiers.

They were clerks who typed supply orders, radio operators who relayed coded messages, truck drivers who moved equipment, nurses aids who bandaged wounds, young women, most between 18 and 30, who had volunteered or been conscripted to serve in non-combat roles.

They had believed the Reich’s promises that they would stay far from danger.

They had believed many things.

When American forces swept through the Ry Valley in late March, these women surrendered.

Not because they wanted to, because there was nowhere left to run.

Among them was a young woman named Anna Vice, 22 years old, former Vermach radio operator, trained to intercept and relay coded communications.

She had grown up in Bavaria in a town with cobblestone streets in a church whose bells rang every Sunday.

Her father had been a postal clerk before the war.

He died in a bombing raid in 19.

Her mother survived but lost everything except the clothes she wore and a photograph of Anna as a child.

Anna kept a diary.

She had been writing in it since she was 14 years old.

Small leatherbound book pages filled with careful script.

She wrote about her training, about the other girls in her unit, about the sounds of artillery getting closer, about the morning they were told to pack everything because they were evacuating.

About the American soldiers who appeared on the road and pointed rifles and said words in English.

she did not fully understand but whose meaning was clear.

Hands up, surrender, war over.

She wrote about the processing camp they were taken to about the separation from male prisoners.

About the medical checks in the questions asked through translators.

About the food they were given.

Real bread, not ursats, not sawdust mixed with potato flour, but actual wheat bread with a soft interior and a crust that cracked when you bit it.

Coffee that was thin but real.

soup with vegetables.

It was more food than they had seen in months, and it terrified them because it meant the Americans had abundance beyond comprehension.

How do you fight people who can feed prisoners better than your own country fed its soldiers after two weeks in the processing camp? They received unexpected orders.

They were being transferred not to a camp in occupied Germany, not to France or Belgium, to America, across the Atlantic, to the enemy’s homeland, to the place where every propaganda poster had told them the monsters lived.

The ship journey took nine days.

600 women in the hold of a transport vessel.

Seasickness, fear, the constant motion of waves.

At night, lying on thin mattresses and rows that stretched into darkness, whispers spread like fever.

What will they do to us there? What happens when we arrive? Why are they taking us so far from home? No one had answers, only fears.

Anna wrote in her diary by flashlight, the small circle of light, her only privacy.

We crossed an ocean today.

I stood on deck for 10 minutes.

They allowed it, and I saw nothing but water in every direction.

I have never felt so small, so far from home, so lost.

The American guards are young.

Some barely look old enough to shave.

They chew gum constantly and speak in accents I cannot penetrate.

One offered me a cigarette today.

I shook my head.

He shrugged and walked away.

It was such a small moment, but I keep thinking about it.

Why offer a cigarette to an enemy? Why that casual kindness? Is it kindness or something else? They arrived in New York Harbor in midappril.

First sight of America, the Statue of Liberty rising from the water green copper against gray sky.

The city beyond massive buildings stretching upward more glass and steel than they had ever imagined.

Traffic, noise, life.

While Europe burned and starved, America seemed untouched.

That was the first shock.

The second came when they were loaded onto trains.

The train journey from New York to Texas took three days.

They traveled in passenger cars, not cattle cars.

Uncomfortable wooden seats, but seats nonetheless.

Windows they could look through, though guards instructed them to keep curtains drawn in populated areas.

They ate sandwiches made with white bread, ham cheese, simple food, common food for Americans, impossible luxury for Germans who had been eating turnup soup, and black bread for years.

Anna watched the landscape change through gaps in the curtain.

Forests gave way to fields.

Fields gave way to plains.

Everything became bigger, flatter, more open.

And then the green disappeared and they entered a landscape unlike anything in Europe.

Brown earth, endless heat shimmering on the horizon, even though it was only April.

This was Texas.

The train pulled into a station near Fort Hood on April 20th.

When the doors opened, the heat hit them like a physical force.

Dry, fierce total.

The air tasted of dust.

The sun burned white.

They stumbled out onto a platform, squinting against light.

Too bright, too harsh.

American soldiers waited with trucks.

The women were loaded into the backs 30 at a time.

Canvas covers provided shade, but no relief from heat.

They drove for 40 minutes on dirt roads, dust coating everything, until they reached a collection of buildings and tents surrounded by barbed wire.

This was their new home.

A prisoner of war camp on the outskirts of Fort Hood.

Temporary structures, canvas barracks, outdoor latrines, a messaul, guard towers at the corners.

600 women in a space designed for 400.

It was not cruel.

It was simply inadequate.

They were given thin mattresses to sleep on two blankets each, a bar of soap, a tin cup.

They were assigned work details, kitchen duty, laundry, cleaning, maintenance, the routine of captivity.

But beneath the routine, fear grew.

Because at night in the barracks, the whispers started.

The propaganda they had been fed for 3 years did not die simply because they crossed an ocean.

It lived in their minds, reinforced by every story they had heard, every poster they had seen, every radio broadcast that warned them what American soldiers did to German women.

And now they were here in America in Texas in the middle of nowhere, far from witnesses, far from help, surrounded by men with guns who had every reason to hate them.

They waited for the mass to drop, for the kindness to end, for the real treatment to begin.

Anna rode on their first night in Texas by candle light while women around her tried to sleep.

We are in the enemy’s heartland now.

Everything here is bigger, hotter, stranger than anything we imagined.

The guards have so much food they throw half away.

They have chocolate.

They have cigarettes for every man.

They have machines for everything.

How did we ever think we could win this war? But more terrifying than their abundance is this question.

What will they do to us now that we’re in their hands, far from any witnesses? Tomorrow we start work.

Tomorrow we learn what they really want.

Nearby, another woman lay awake.

Gerta Hoffman, 28 years old, truck driver, practical strong, the kind of woman who fixed problems rather than complained about them.

She had lost her brother on the Eastern Front, killed at 19 in some nameless village in Russia.

She had lost her fiance at Stalingrad, missing, presumed dead.

She had lost everything except the ability to keep going.

Now she lay on a thin mattress in a Texas prisoner camp and calculated odds.

How many women? How many guards? How far to any border? How long could they survive if they ran? The math never worked.

There was nowhere to run.

Nothing to do but wait and see what came next.

Two rows over the youngest of them tried not to cry.

Lisa Fiser, 19 years old, nurse’s aid.

She had volunteered because it seemed noble.

She had imagined helping wounded soldiers in clean hospitals behind secure lines.

Instead, she had ended up in a field station that moved every 3 days where men screamed on tables made of doors, where there was never enough morphine and never enough time.

She had seen terrible things, but she had never been as afraid as she was now.

Because in the field stations, at least she had a purpose.

Here she was just a prisoner, just a body, just a young German woman in enemy hands.

She pulled her blanket over her head and prayed silently, first time since childhood.

Please let us survive.

Please let them follow their rules.

Please let the propaganda be wrong.

The next morning came too early.

bugle call from the main base echoing across the camp.

Women stumbled out of barracks, formed ragged lines for roll call.

An American sergeant called out numbers.

They answered in German.

Yah.

Here, present.

He made check marks on a roster.

Dismissed them to breakfast.

The messaul was a long tent with tables and benches.

Women lined up with tin trays.

American cooks served oatmeal, wheat coffee, a slice of bread.

The oatmeal was thin but hot.

The bread was real.

The coffee tasted of chory, but it was coffee.

They sat and ate in silence.

This was better food than the last months in Germany.

No one said it out loud, but everyone knew.

After breakfast, work assignments.

Anna and Margaret Klene, a former supply depot clerk, were assigned to kitchen duty.

They reported to the main base kitchen separate from the prisoner mess.

An American sergeant met them there.

Black man, 45 years old, career army.

His name was James Miller.

He looked at them with tired eyes and said in English.

They barely understood.

You follow instructions.

You work clean.

You don’t touch nothing you ain’t supposed to.

Clear.

They nodded.

He showed them how to operate the industrial equipment.

How to wash pots in the enormous sinks.

How to scrub floors, how to sort supplies.

He was all business.

No small talk, no smiles, just instructions and expectations.

They worked for three hours.

Their hands turned red from hot water.

Their backs achd from bending.

But it was work.

It was purposeful.

It kept their minds busy.

And then around in the morning, Miller started cooking breakfast for the American staff.

Officer’s mess.

He pulled out a cast iron skillet, placed it on the stove, turned the heat high.

He opened a refrigerator, a real electric refrigerator, humming with cold, and pulled out packages wrapped in white paper.

He unwrapped them.

bacon.

Strips of pork belly, pink and white, marbled with fat.

The smell hit Anna and Margaret like a freight train.

Real bacon.

They had not smelled real bacon in 3 years.

The sound of it, that sizzle, that pop of fat in the hot skillet, it was obscene.

Criminal.

While they had been eating turnipss and sawdust bread while children in Germany starved here, was this American soldier casually cooking enough bacon to feed their entire barracks for a week just for breakfast? just for one morning.

They stood frozen staring, their stomachs twisted, their mouths watered.

They could not look away.

Miller glanced at them, saw their faces, saw the hunger that could not be hidden.

He said nothing for a moment, just kept cooking.

The bacon crisped.

He flipped it with a fork.

More sizzling.

The smell intensified salt and smoke and fat primal and devastating.

Then without looking up, Miller [clears throat] said, “Y’all want some?” Anna and Margaret froze.

Was this a test, a trap? Were they supposed to refuse? Except what was the right answer? Miller, still not looking at them.

I asked if you want some bacon.

I got extra.

He plated two strips on a small dish, set it on the counter near them.

Turned back to his cooking.

They stood there, not moving.

The bacon sat on the plate, still hot edges, crispy center, chewy.

Steam rose.

The smell wrapped around them.

Margaret reached out first, picked up one strip, bit into it, her eyes closed.

Anna took the other, put it in her mouth, bit down.

The flavor exploded.

Rich, savory, real salt and smoke and fat textures and tastes they had forgotten existed.

The bacon was perfect.

Crispy edges, chewy middle grease coating their lips.

Anna’s hands shook.

Margaret made a sound, not quite a sob.

They stood in an enemy kitchen eating enemy food cooked by a man Nazi propaganda had taught them to consider subhuman, and it was the best thing either of them had tasted in years.

That’s when Anna realized something fundamental.

Everything is upside down here.

They worked the rest of the shift in silence.

Miller said nothing more.

Just cooked and served and cleaned.

When they were dismissed back to the prisoner camp, Anna and Margaret walked together, not speaking, both processing the same confusion.

Why would he share food? Why that casual generosity? What did it mean that night in the barracks? They did not mention the bacon.

They did not talk about the kindness because kindness from the enemy was more frightening than cruelty.

Cruelty they understood.

Kindness suggested complications they were not ready to face.

Days passed.

A routine established itself.

Wake at , roll call at , breakfast at , work from 7 to noon, lunch, more work from 1 to 5, dinner at , free time until , lights out.

The routine was bearable.

The work was hard, but not brutal.

The food was adequate.

They were not abused.

They were not hurt.

But they waited.

They waited for the moment when everything would change.

when the nice treatment would stop and the real intentions would be revealed.

Because the propaganda had been so clear, so consistent, so detailed about what Americans did to capture German women.

It could not all be lies.

It had to be true.

At night, the rumors spread.

Whispers in darkness.

They separate women at night.

Take them to officer’s quarters.

I heard they do medical experiments.

Why else would they feed us? keep us healthy.

We’re no use to them unless the whispers never finished, just trailed off into implications too terrible to voice.

A woman named Bridget Müller became the voice of fear.

30 years old, former secretary, she had worked in occupied Poland.

She said she had seen what soldiers did when no one was watching.

These Americans, she insisted they smile and give us bacon and say, “Yes, ma’am.” But they’re still men.

They’re still the enemy.

They’re still soldiers far from home with power over us.

This niceness is how they make you trust them.

Then they take what they want.

Most women wanted to believe otherwise.

But belief without evidence is just hope.

And hope felt dangerous.

Ruth Werner spoke up once, 32 years old, translator, married.

Her husband was a prisoner in France.

The Red Cross had informed her he was alive being held in an American P camp.

She clung to that information like a lifeline.

The Geneva Convention, she said quietly.

The Red Cross monitors, they have rules.

Bridget cut her off.

The Geneva Convention is words on paper.

Paper doesn’t stop anything.

And in the darkness, no one disagreed.

On their 18th day in camp during morning roll call, Captain Thomas Mercer addressed them.

38 years old, Texas native, career army, tired eyes but firm voice.

He spoke through a translator, a German American soldier who rendered his words precisely.

Tomorrow morning, 0600 hours, full camp medical inspection.

All personnel report to main courtyard.

This is mandatory.

Dismissed.

That was all.

No explanation, no details, just the announcement.

Panic spread like wildfire.

Medical inspection.

Those words could mean anything.

In the camps they had heard about medical inspection meant selection.

meant experimentation meant the kind of procedures you did not survive.

They did not know what it meant here, but their imaginations filled the gaps with horrors.

That night, no one slept.

They lay in darkness, each woman alone with her fears.

Some prayed, some cried silently, some just stared at the canvas ceiling and waited for dawn.

Anna wrote in her diary, hand shaking so badly her script was barely legible.

Tomorrow morning we line up for inspection.

I have lived through bombings.

I have lived through starvation.

I have lived through watching my city burn.

But tonight I am more afraid than I have ever been because bombs are random.

Starvation is slow.

But tomorrow men will look at us.

Men with power.

Men who won.

Men far from their homes and their wives and any witnesses.

Tomorrow we discover if the propaganda was true.

Tomorrow we learn if mercy exists.

I don’t think it does.

God help us.

Emar Roth unwrapped her hands and looked at her fingers.

Purple, black.

Two nails had fallen off.

Frostbite from the retreat hidden for weeks because she was terrified that if they saw she was damaged, they would decide she was useless.

What happens to useless prisoners? She rewrapped her hands in strips torn from an undershirt.

If they made her show them tomorrow, she would have no choice.

But until then, she would hide it.

Lisa, the youngest, curled into a ball and shook.

Margaret held her whispered reassurances that sounded hollow even to her own ears.

It will be all right.

They have rules.

They won’t hurt us.

Words without conviction.

Gerta sat upright on her mattress, eyes open, staring into darkness.

Her mind cycled through scenarios, all bad.

She thought about her brother, dead at 19.

She thought about her fianceé lost at Stalenrad.

She thought about everyone she had already lost and she made a decision.

If they were going to die, at least they would die without begging.

At least they would maintain some dignity.

Ruth clutched a photograph of her husband.

Criest warned the only possession she had carried across the ocean.

She looked at his face in the dim light and prayed, “Please let the Americans follow their rules.

Please let them treat us the way they treat him.

Please let mercy be real.

The night stretched forever.

But dawn came anyway.

before the bugle.

Guards moved through the barracks.

Flashlights cutting through darkness.

Voices in English.

Rouse.

Rouse.

They had learned that word.

Out.

Move.

Now the women stumbled outside into gray pre-dawn light.

Cool air but heat coming.

They formed lines in the main courtyard.

600 women on bare dirt.

No one had told them what to wear.

Some wore their old vermached uniforms.

Some wore the cotton dresses.

All wore fear.

The courtyard was not large, maybe 50 m across, bare dirt with patches of mud from recent rain.

Single fence on three sides, guard towers at corners.

The sky was gray pink sun not yet over horizon.

The air smelled of dust and canvas and the sharp metallic scent of fierce sweat.

In the distance, cattle loaded, a rooster crowed, normal sounds from a world that suddenly felt very far away.

The women stood in uneven rows, shoulderto-shoulder.

Some had buttoned their clothing wrong in the darkness.

Others had no time to button at all.

They waited, silent, frozen.

600 women holding their breath.

Anna stood in row three, position 8.

She counted the women in her line.

23.

She counted them twice.

It kept her mind busy.

Stopped her from thinking about what came next.

Behind her, someone coughed wet and rattling.

Pneumonia spreading through the camp.

No one had reported it.

Too afraid of what reporting illness might mean.

Gerta was in row one, position five, near the front.

She would be inspected early.

Her face was stoned, but inside her heart hammered.

She had made peace with death before.

She would do it again if necessary.

Lisa stood in row four, shaking so badly her teeth chattered.

She grabbed onto the woman next to her for support.

The woman said nothing, just let her hold on.

They waited as the sky lightened as the sun touched the horizon as the heat began to build.

And then the Americans arrived.

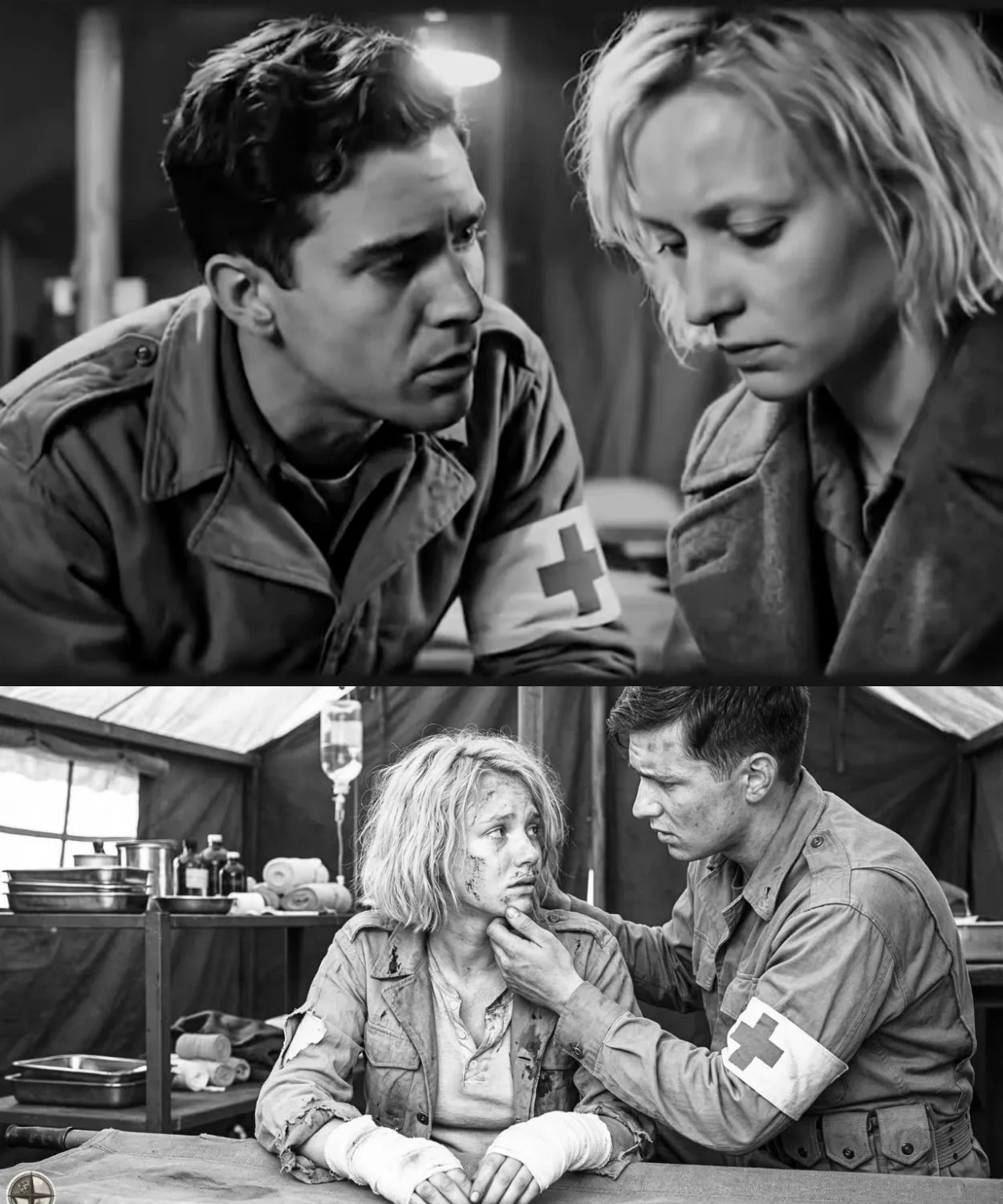

Captain Mercer entered the courtyard with his medical staff.

He carried a clipboard.

Behind him, a young medic carried a canvas medical bag.

A nurse followed, also carrying his supplies.

A doctor in a French uniform walked beside them.

Guards took positions around the perimeter, rifles lowered but visible.

Mercer walked to the front of the formation.

He looked out at 600 terrified women, and his face showed nothing.

No anger, no satisfaction, no emotion at all, just tired professionalism.

He began walking down the first row slowly, deliberately.

He stopped at each woman, looked her up and down, wrote something on his clipboard.

His boots made soft sounds in the dirt.

The only other sound was breathing.

600 women breathing in ragged unison.

The medic followed him.

Young man, mid20s.

Name was Corporal James Hartley from Oklahoma.

He had been an Army medic for two years.

He had treated gunshot wounds in foxholes.

He had seen boys die screaming.

This morning, his orders were simple.

Check for signs of illness.

Malnutrition infection.

Flag anyone who needed immediate treatment.

Not complicated, just medical triage.

But looking at these women’s faces, seeing the terror in their eyes, he began to understand something his briefing had not prepared him for.

They think we’re going to hurt them.

They think this is something else entirely.

Mercer reached the end of the first row, turned, started down the second row, coming closer to Gerta.

She watched him approach.

Four women, three women, two women, one.

He stopped in front of her, looked at her face, her posture, her condition, and then he spoke.

Texas draw, firm but not harsh.

Three words.

Open your coat.

Three words in English.

But Gerta had learned English in school years ago.

She understood perfectly.

Time stopped.

This was it.

This was the moment every poster, every broadcast, every warning had prepared her for.

This was when the nice guard who gave them bacon would step aside for the officer who took what he wanted.

This was when protocol ended and power began.

Her hands moved to the buttons of her coat.

They would not obey.

Her fingers were stiff, frozen, not from cold, from terror.

She thought about her brother, dead at 19 on the Eastern Front.

She thought about her fianceé, missing at Stalenrad.

She thought about the life she’d had and the life she wouldn’t have.

She unbuttoned her coat.

First button, second, third.

She pulled the fabric apart underneath a thin gray shirt hung loose on her frame.

She had lost 15 kg since January.

Her collarbone jutted sharp, her ribs showed through the fabric.

She stood there, waiting, exposed, for hands to reach for violence, for everything she had been promised would happen.

Corporal Hartley stepped forward, but he did not touch her.

He looked, his eyes scanned professionally clinically.

He looked at her collarbone.

Severe protrusion meant malnutrition.

He looked at her neck.

Visible veins meant dehydration.

He looked at her hands trembling.

He looked at her face.

Pale but not dangerously so.

He listened to her breathing.

Steady, not labored.

He wrote on his chart.

Moderate malnutrition, stable condition.

Monitor, he signaled the nurse.

Lieutenant Mary Callahan stepped forward.

32 years old, Army nurse from Boston, Irish Catholic.

She had volunteered in 1942.

She had seen terrible things in field hospitals.

She had held dying boys’ hands and written letters to their mothers.

This morning, her job was simple.

Provide blankets to prisoners showing signs of exposure.

Check vitals on anyone flagged.

Basic medical support.

She handed Gerta something.

A wool blanket, gray, clean, folded.

She said something in English.

Gerta did not catch the words, but the gesture was clear.

Take it for you.

Hartley moved to the next woman.

That was it.

That was all.

No hands, no violence, no assault, just a glance, a note on paper, a blanket.

Gerta stood frozen, coat still open, blanket in her arms, mind unable to process.

What just happened? What was supposed to happen? Why didn’t anything happen behind her? Dana watched, saw the whole thing, the order, the compliance, the examination, the blanket, the moving on.

Her brain refused to accept it.

This can’t be right.

This can’t be all.

But the process continued row by row, woman by woman.

Open your coat.

Examination note.

Next.

Some women complied immediately, learning from those before them.

Some hesitated.

One woman tried to close her coat after opening it.

Sergeant Dawson, the guard, stepped forward, not threatening, just firm.

The order was given.

Keep it open.

She complied.

When Mercer reached Anna, she did not wait for the command.

She opened her coat, stared straight ahead at the horizon, made herself disappear inside her own mind.

Hartley scanned her.

Moderate weight loss, no urgent signs, made note, moved on.

Anna stood there, hands shaking so badly she could not button her coat back up.

Nurse Callahan approached, said something gentle in English, reached toward the coat.

Anna flinched violently.

Callahan stopped, raised her hands, palms out.

universal gesture.

I mean no harm.

She pointed at the buttons, mimed helping.

Anna nodded barely.

Callahan buttoned three buttons with quick professional efficiency.

Said something soft, walked away.

Anna’s brain still could not process this.

The inspection continued.

90 minutes.

600 women.

Most were examined and dismissed, but some were pulled aside.

22 women flagged for immediate attention.

17 taken to the medical tent at the edge of the compound.

Emma’s turn came in row two.

She opened her coat.

Hartley saw immediately how stiffly she held her hands.

He stopped.

“Show me your hands,” the translator repeated in German.

Emma hesitated.

This was the moment she had dreaded, her secret exposed.

“Show me your hands, ma’am.” She extended them, the cloth wrapping she had made.

“Remove the cloth.” She unwrapped them slowly.

Her fingers were modeled purple red.

Two fingernails black and dead.

Advanced frostbite.

Weeks old.

Hartley’s jaw tightened.

First emotion anyone had seen from him.

He looked at the French doctor.

Dr.

Lauron Bowmont, 45 years old.

Had seen the worst of war.

He stepped forward, examined without touching.

In English, too long, two fingers we can’t save.

But if we treat now, we can save the hand.

Hartley signaled.

Emma was gently guided out of formation toward the medical tent.

She did not resist.

Too weak, too confused.

As she was led away, she looked back at the other women.

Her face asked the question they were all thinking.

What’s happening? This isn’t what they said would happen.

When the inspection finally ended when the last woman had been examined and the last note had been made, Captain Mercer dismissed them back to barracks.

The women stumbled away, minds reeling.

They had expected horror.

They had received a medical examination.

They had expected violence.

They had received blankets and notes on clipboards.

In the barracks, they sat in stunned silence.

Finally, someone spoke.

Ruth Werner voice shaking.

They didn’t touch us.

Silence.

Gerta stared at the blanket in her hands.

Greywool American military issues still warm from storage.

They gave me this.

The nurse just handed it to me like I was someone who might be cold.

Margaret the observer.

the one who always noticed details.

It was medical.

Just medical.

They were looking for sickness.

Bridget the cynic tried to hold the line.

Or it’s a trick.

Make us trust them first.

Then Gerta snapped suddenly angry.

Then what? They had us.

All of us.

Coats open.

Surrounded by armed guards.

If they wanted to hurt us, why didn’t they? No one had an answer.

Anna opened her diary.

Her hands still shook.

She wrote, “Today I learned that what you expect and what happens are not always the same thing.

I don’t know what this means.

I don’t know if we’re safe, but I know this.

I opened my coat and they gave me nothing but a glance and a note on paper.

That is not what I was taught to expect from the enemy.” She closed the diary.

Outside, the Texas sun climbed higher.

The heat built.

Guards walked their rounds.

Cattle load in the distance.

And in the medical tent, Emma was about to discover something that would make her question everything she’d been told about Americans.

And Lisa, lying on a cot with pneumonia she had hidden for weeks, would learn the meaning of the word mercy.

But that understanding would take time because fear once planted deep does not die quickly.

It lingers.

It whispers.

It waits for proof that it was wrong.

And in a prisoner camp in Texas in the spring of 1945, that proof was only beginning to emerge.

Inside the medical tent, everything was different.

Canvas walls, but clean.

Six Cs with actual mattresses thin but real.

A small wood stove kept the temperature bearable against the Texas heat that would build by noon.

The smell was sharp and chemical.

Iodine, iced soap, coffee, real coffee, strong and bitter.

The sound was muted, almost peaceful.

A low murmur of English voices, medical instruments clinking softly against metal trays.

Someone coughing wet and painful.

Light filtered through the canvas, golden and warm like being inside a lantern.

Emma Roth sat on the edge of a cot, her damaged hands resting on her knees.

She had been led here an hour ago, guided gently by the American nurse, whose name she did not know.

No one had heard her.

No one had even raised their voice.

But she was still afraid because this gentleness felt like the calm before something terrible.

Dr.

Laurent Bowman approached French army physician attached to American forces, 45 years old.

He had kind eyes behind wire- rimmed glasses and moved with the careful efficiency of a man who had seen too much suffering to waste time on anything unnecessary.

He sat on a stool across from Emma and spoke through the translator, a [clears throat] German American private, who rendered each word precisely.

The damage is severe.

You should have reported this weeks ago.

Emma looked down at her purple fingers.

I was afraid.

Afraid of what? That if you knew I was damaged, you would dispose of me.

Long silence.

The doctor’s face showed no judgment.

Just a deep weariness.

Finally, he spoke.

Mammoiselle, we are doctors.

We treat patients.

You are a patient.

That is all you need to be.

Simple words.

Professional.

No drama.

But they cut through something in Emma’s chest.

A knot she had been carrying since the day she was captured.

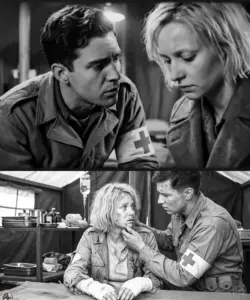

The nurse Lieutenant Mary Callahan brought a tray on it.

A bowl of soup steaming in the warm tent.

Real vegetables floating in broth.

Carrots.

Potatoes.

Something that might be chicken.

Also, a piece of bread, white and soft, the kind Emma had not seen since before the war.

A glass of water.

Clean bandages folded beside it.

Callahan placed the tray on a small table next to Emma’s cot.

She said something in English.

Emma did not understand, but the gesture was clear.

Eat.

It’s for you.

Then she moved to check on another patient.

Emma stared at the soup.

Steam rose, carrying scents that made her throat tighten.

Salt, vegetables, fat, real food.

She picked up the spoon.

Even that small motion hurt her damaged fingers.

She brought the spoon to her lips.

The broth was hot, salty, rich beyond anything she remembered.

She took another spoonful, a piece of carrot, soft, and sweet.

Another spoonful.

Potato buttery somehow.

Her hands shook.

The spoon rattled against the bowl.

She ate slowly each bite, a question she could not answer.

Why are they giving this to me? Why waste food on a German prisoner? Why waste medicine? Why am I not dead? She ate the soup.

She ate the bread.

It tasted like clouds.

When she finished, she sat holding the empty bowl tears running down her face.

Not from pain, from something she could not name.

Across the tent, another patient lay on a cot, barely conscious.

Lisa Fiser, 19 years old, the youngest of them.

She had collapsed during the morning work detail 2 hours after the inspection.

High fever, coughing blood.

Pneumonia [clears throat] advanced to the point where her lungs crackled with every breath.

She had hidden it for weeks, terrified that showing weakness would mean death.

Now she was too sick to hide anything.

Dr.

Bowman examined her with the same careful efficiency he had shown Emma.

He listened to her lungs with a stethoscope, checked her pulse, looked at her eyes, her throat, the color of her skin.

Then he stood and spoke to Captain Mercer who had come to check on the flag prisoners without antibiotics in rest three days, maybe four.

She is 19 years old and she is dying.

Mercer’s face showed nothing, but he nodded once.

Authorized penicellin.

Per Geneva Convention, prisoners of war receive same medical care as our troops.

Process it.

The decision took 30 seconds.

No debate, no consideration of cost or a supply, just protocol.

Rules followed because rules existed.

Lisa drifted in fever dreams.

Her mother’s voice calling from far away.

Bombs falling on Berlin.

The sound that never left her even in sleep.

The ship across the Atlantic rolling endlessly.

Anna’s face saying it will be okay, but not believing it.

The officer saying, “Open your coat, waiting to die.

But why is the bed soft? Why does someone keep putting a cool cloth on my forehead? Why can I hear a woman singing in English? Why hasn’t anyone hurt me yet?” The fever broke reality into pieces.

Past and present merged.

She was in a field hospital in Germany.

She was on a ship.

She was in Texas.

She was home.

She was nowhere.

Time meant nothing.

Pain meant everything.

But through it all, a constant presence.

Nurse Callahan checking her vitals every hour, adjusting her blankets, bringing water and coaxing her to drink, wiping her face with cool cloths, speaking softly in English words Lisa did not understand, but whose tone carried something like care.

At in the morning, when the tent was dark, except for a single kerosene lamp, Lisa woke briefly.

Lucid moment in the fever, she turned her head and saw Callahan sitting in a chair beside the stove, reading a book by lamplight.

The nurse glanced up, saw Lisa’s eyes open, came over immediately, checked her forehead, brought water, helped her drink, said something gentle.

Lisa’s thought too weak to voice.

She stayed.

She didn’t have to stay.

Why did she stay? Then the fever took her again.

3 days passed.

In the medical tent, Emma’s hands were treated.

Dr.

Bowmont performed surgery under local anesthetic.

Two fingers amputated at the second knuckle.

The damage too severe to save.

The remaining fingers cleaned and bandaged.

Antibiotics administered, pain medication given.

Through it all, nurse Callahan held Emma’s other hand.

She hummed a tune Emma did not recognize.

Amazing Grace, a hymn.

Callahan hummed it during every difficult procedure.

It helped her stay calm and somehow it helped Emma too.

Lisa received penicellin injections every 6 hours.

The miracle drug still relatively new, still reserved for soldiers and critical cases.

But protocol said prisoners received the same care as troops.

So Lisa received it.

The fever began to drop.

The breathing eased.

Color returned to her face.

On the fourth day, she woke fully lucid for the first time.

Nurse Callahan was changing the water in a basin nearby.

Lisa watched her for a long moment, gathering strength.

Then, through the translator, who came by twice daily, she asked a question, “Why are you helping me?” Callahan looked at her.

Tired face, kind eyes, she answered simply, “Because you have pneumonia, and I am a nurse.

That is what nurses do.

” Lisa started crying, not from pain, from incomprehension.

But I am German.

We are enemies.

We, Callahan’s answer, gentle and firm.

The war is over, honey.

You are 19 years old with a pneumonia.

That is all you are right now.

That is all that matters.

The words settled into Lisa like stones into water, sinking deep, creating ripples.

She would remember them for the rest of her life.

Back in the barracks, the women who had not been taken to the medical tent processed their own confusion.

Days passed, work continued.

The routine remained, but everything felt different now.

The inspection had cracked something open, a possibility they had not dared consider.

What if the propaganda was wrong? What if the Americans were not monsters? What if mercy was real? At night, they gathered in Anna’s section of the barracks, whispered conversations in the darkness, trying to make sense of what they had experienced.

One woman spoke first.

They didn’t do anything.

They just looked.

They gave Gerta a blanket.

They took Emma to a medical tent.

She’s being treated.

Lisa has pneumonia.

They’re giving her medicine.

The words hung in the air.

Evidence accumulating.

But Bridget Muller, the skeptic, the one who had warned them from the beginning, tried to hold the line.

It is a trick.

It has to be.

They are making us compliant, making us trust.

Then when we are vulnerable, Gerta cut her off.

She was still holding the blanket they had given her.

She had not let it go for 3 days.

Then what? Bridget.

They had us, all of us.

Coats open, surrounded, armed guards.

If they wanted to hurt us, why didn’t they? Silence.

Ruth Werner, the translator, the one whose husband was in American hands in France, spoke quietly.

The Red Cross said prisoners of war are treated according to Geneva Convention.

Maybe it is true.

Maybe the propaganda lied.

Margaret Klein, the former clerk who had processed supply manifests, spoke slowly, carefully.

I have been thinking about the things I saw back in Germany, the shipments I processed, medical supplies going to camps, but the quantities never matched hospital needs and the destinations.

Some went to places that were not hospitals at all.

The silence that followed was heavier.

This was dangerous territory.

Thoughts they had not allowed themselves to think.

Anna, the intellectual, the dyrus, voiced what they were all beginning to realize.

If they lied about the Americans, what else did they lie about? The question sat among them like a physical presence.

No one wanted to touch it, but it would not go away.

Gerta, ever practical, tried to find solid ground.

I don’t know if they are good or evil, but I know this.

They have rules and they are following them.

That clipboard, the medical exam, that was protocol.

They were following protocol.

Anna pushed further.

But why follow protocol? Why not just do whatever they want? They won.

We lost.

They have the power, Margaret answered slowly.

Because maybe their system is different.

Maybe their rules matter more than personal feelings.

Maybe they actually believe in their laws.

A younger woman background prisoner whose name was Petra spoke up.

Americans always talked about freedom, democracy, individual rights.

We were taught that was propaganda.

But what if it is not? What if they actually believe it? Bridget’s voice resisting but weakening.

Believe what? That even enemies deserve dignity.

That prisoners are people.

That she stopped because she heard what she was saying.

Ruth finished the thought.

Yes, exactly that.

That even enemies are human.

That is what the Geneva Convention is.

Rules that say you treat prisoners as humans anyway.

Even if you hate them, even if they are the enemy.

Anna’s voice quiet but intense.

That is opposite of everything we were taught.

We were taught to hate, to fear, to see enemies as monsters.

Gerta nodded, and they were taught the same about us.

But their system, their laws, their rules, their system said, “Treat prisoners as humans anyway.

Follow the rules.” The conversation went on for hours, circling, probing, testing, until finally Anna spoke the realization that had been forming.

I understand now it [clears throat] was not kindness.

It was civilization.

They were not being nice to us.

They were following rules that their civilization built.

Rules that say some things you don’t do even in war, even to enemies.

That is not weakness.

That is strength.

That is something we forgot.

long silence.

Someone in the darkness whispered, “We were on the wrong side.” No one contradicted her.

While the women struggled with these revelations in their barracks, the American officers sat in their own mass hall processing their own confusion.

Captain Mercer, Corporal Hartley, and Lieutenant Callahan ate a late dinner.

Beans and cornbread, coffee, the simple food of a military base far from combat.

Hartley spoke first.

The frostbite case.

Emma, she hid it for weeks.

She was terrified we would see her hands.

Why? Callahan answered because she thought we would kill her for being useless.

Or worse, Mercer Texas draw tired and slow.

Propaganda.

Gerbal spent years telling Germans we are monsters.

Cannot blame them for believing it.

Silence while they ate.

Hartley continued, “That girl with pneumonia.

Lisa, she is 19, younger than my sister.

When I gave her the penicellin, she cried.

Not from pain.

She cried because she could not understand why we would waste medicine on her.

Callahan’s voice was soft.

They don’t trust kindness.

They think it is a trap.

Mercer leaned back, coffee cup in hand.

My grandfather fought in the first war.

Came home saying the Germans were just men.

Scared men fighting for their country.

Same as us.

Command asked me, “How do we handle the women prisoners?” I said, “Same as the men.” Geneva Convention by the book.

No exceptions.

But I did not expect them to be so afraid of basic human decency.

Hartley asked the question they were all thinking.

What happens when they go home? When they tell people that American camps were not death camps, Mercer stared into his coffee.

Maybe they help break the propaganda.

Maybe it matters.

Or maybe it is too late.

Maybe the damage is permanent.

The conversation ended there because none of them had answers.

They were just soldiers following orders, doing their jobs.

But they were beginning to understand that sometimes doing your job right has consequences you never intended.

On Emma’s fourth day in the medical tent, she was cleared to return to the barracks.

Her hands were bandaged.

Her right hand had only three fingers now.

The amputation sites were healing cleanly.

Dr.

Bowmont had done excellent work.

Emma could move her remaining fingers.

She would be able to write again, work again, live again, just differently.

The women gathered around when she entered the barracks, quiet, waiting.

Emma sat down slowly, still weak.

She looked at their faces and spoke.

They amputated two fingers.

The frostbite was too advanced.

Dr.

Bowman explained everything before they did it through a translator.

He said we cannot save these two but we can save your hand and your arm if we act now.

Do we have your permission? Stunned silence.

Someone whispered.

He asked permission.

Yes.

And when I said yes they gave me something.

Morphine I think so I would not feel it.

And the nurse Callahan she held my other hand during the surgery.

She did not have to.

I am a prisoner.

I am German.

But she held my hand and she hummed a song.

I don’t know what song, but she stayed.

Emma’s voice cracked.

They tried to save all my fingers.

They really tried.

They used antibiotics.

They cleaned the wounds every day.

They gave me hot soup and bread.

And when they could not save two fingers, Dr.

Bowman said, “I am sorry.

We could not do more.” He was sorry.

Sorry to a German prisoner.

I don’t understand this.

Gerta spoke quietly.

They followed their rules.

Emma shook her head.

It is more than rules.

The nurse did not have to hold my hand.

That was not rules.

That was human.

No one had a response to that because it was true.

There was a difference between following protocol and being kind.

And somehow these Americans were doing both.

The next revelation came by accident, a supply error.

Some quartermaster somewhere miscalculated or misread or simply made a mistake.

The result was that the Fort Hood prisoner camp received double rations for 3 days.

American guards, rather than let food spoil or go to waste, decided to distribute the extra to the prisoners.

Why not? It was just going to be thrown away otherwise.

The morning of the first day of abundance, the women lined up for breakfast, expecting their usual thin oatmeal and slice of bread.

Instead, the cooks served scrambled eggs, real eggs, golden and fluffy bacon, multiple strips per person, crispy and glistening.

Toast made from white bread, soft and warm butter, real butter that melted into the toast.

Coffee hot and strong.

Actual American coffee from real beans.

The mess hall fell silent.

600 women staring at their trays.

Anna sat with her tray in front of her, unable to move.

The eggs were yellow, not gray like Ursat’s eggs, not brown like the potato substitutes, but golden yellow.

They were fluffy, salted, perfectly still, steaming.

The bacon was crispy at the edges, chewy in the middle, fat glistening.

The toast was soft white bread, real wheat, real flour spread with actual butter that melted into the warm surface.

And the coffee.

God, the coffee.

Hot, strong, bittersweet American coffee made from real beans, not roasted acorns or chory substitute.

She picked up her fork, cut into the eggs, brought a bite to her mouth.

The taste was overwhelming.

rich, savory, real.

She chewed slowly, swallowed, took a bite of bacon, the salt and smoke and fat, the crunch, the flavor that filled her whole mouth.

Margaret sat across from her.

They looked at each other.

This is more food than we saw in the last 6 months of the war.

Margaret nodded slowly.

This is normal for them.

Look at the guards.

They are eating the same thing and they are barely paying attention.

This is not special.

This is just breakfast.

Around them, the realization spread like fire.

America was not starving.

Not even close.

While they had rationed turnipss and made bread from sawdust, Americans had eggs and bacon for every soldier every morning.

While they had boiled potato peels, Americans threw away food.

This was not just military defeat.

This was understanding scale, understanding resources, understanding that the war had never been even remotely close.

Ruth Werner started laughing, then crying, then both at once.

We lost to people who have too much food.

We lost to people so rich they can give prisoners eggs and bacon and not even notice the expense.

How did we ever think we could win? She could not finish.

None of them could.

The breakfast sat heavy in their stomachs.

Not from the food itself, though it was more than they had eaten in a single meal in years, but from what it represented, the sheer abundance, the casual waste, the impossible distance between what they had been told and what was real.

That night, the breaking point came.

Bridget Mueller, who had been the voice of skepticism, the one who warned them not to trust the one who insisted it was all a trick, she stood up in the barracks and addressed them all.

I cannot do this anymore.

I cannot live in this uncertainty.

Everyone stopped, watched.

Her voice was shaking.

For three years, I believed.

I believed we were right.

I believed we were defending civilization.

I believed the allies were evil, that they wanted to destroy us, that capture meant suffering worse than death.

I believed every poster, every broadcast, every warning.

And I came here expecting to die, expecting horror, expecting everything we were promised.

And instead, they gave me oatmeal and medical exams and blankets.

And today, they gave me eggs and bacon like I was a person.

And now I do not know what I believed.

I do not know what was true.

I do not know who I am.

She broke down sobbing.

Gerta approached, put a hand on her shoulder.

You are a woman who survived.

That is enough.

But Anna challenged.

No, she is right to ask.

We all need to ask because if they lied about the Americans, if the propaganda about them being monsters was a lie, then what else was a lie? Margaret spoke the words no one wanted to say, the reasons for the war, the enemies they told us about, the things they said had to be done, the places I sent supplies to.

If they lied about this, the young woman Petra interrupted.

Her voice was strained.

My brother was SS.

He came home on leave in 1944.

Got drunk, started crying, said he had seen things he could never unsee, things he was ordered to do.

He killed himself a week later.

I thought he was weak.

I thought he could not handle being a soldier.

But now I think he knew.

He knew something we didn’t.

He knew we were She could not say it.

Ruth said it for her.

That we were the evil ones.

That we were the monsters.

The silence was complete.

No one moved.

The words hung in the air like smoke.

Anna spoke into that silence.

Her voice was steady, but her hand shook.

I do not know if we were evil.

I do not know if every German was evil.

I was a radio operator.

I typed codes.

I did not hurt anyone.

But I was part of a system.

A system that lied to us about enemies so we would not question what we were doing.

And those lies almost got us killed here.

We almost died from fear of people who were just following rules that said treat prisoners humanely.

We were taught to expect monsters.

We found human beings.

That is the lesson.

That is what I am taking from this.

Propaganda kills in more ways than we understood.

Gerta added her practical wisdom.

And systems matter.

Their system, their laws, their Geneva Convention, their military protocol, their system saved us even though individuals might have wanted revenge.

That is civilization.

Real civilization, not propaganda about civilization.

Actual rules that protect even enemies.

The conversation continued until lights out and beyond voices in darkness.

Processing, questioning, rebuilding understanding from the ground up.

It was painful work.

Everything they had believed was suspect now.

Everything they thought they knew had cracks in it.

But through the pain, something else grew.

A fragile hope.

If the propaganda about Americans was wrong, maybe other things could be different, too.

Maybe the world was not as simple as they had been taught.

Maybe enemies could be human.

Maybe mercy was possible.

Maybe they could go home and build something better from the ruins.

Maybe it was a small word.

But it was more than they had the day before.

And in the medical tent, Lisa Fischer slept peacefully for the first time in weeks, breathing easily, fever gone alive, because an enemy nurse had followed the rules and stayed up nights to make sure a 19-year-old German girl did not die alone in a foreign land.

The awakening had begun.

Not sudden, not complete, but real.

And once it started, there was no going back to the comfortable certainties of propaganda.

Truth once glimpsed insists on being seen.

June 1945, Germany surrendered.

The war in Europe was over.

Victory declared, flags raised, celebrations in American streets.

But in the prisoner camp near Fort Hood, the mood was different.

Relief, yes, but also uncertainty.

What came next? The processing for release began slowly.

paperwork, interviews, medical clearances, transport arrangements, the machinery of repatriation grinding forward with military efficiency.

Each woman was called individually to meet with Captain Mercer for an exit interview.

Standard procedure, required documentation, any complaints about treatment during captivity.

Anna sat across a desk from Mercer in a small office tent.

He had his clipboard.

She had her hands folded in her lap.

The translator stood nearby.

Any issues during your captivity to report Anna looked at him.

This tired American officer who had given the order that terrified her, who had followed protocol when hatred would have been easier.

She chose her words carefully.

No sir, I expected monsters.

I found men and women following rules.

I cannot say I am grateful to be a prisoner, but I am grateful to be alive.

I did not think I would be.

Mercer made a note.

His face remained neutral.

professional.

He dismissed her with a nod.

Next.

But that night in his own quarters, Mercer wrote in a journal he had kept since Normandy.

The entry would not be discovered until decades later, found by his daughter cleaning out his belongings after his death in 1994.

These German women arrived terrified.

They had been taught we were savages.

We just followed Geneva Convention protocol, medical care, adequate food, humane treatment, basic military procedure.

But to them, it was revolutionary.

Makes you think about the power of propaganda.

How fear can be weaponized.

How lies can make people expect horrors that never come.

We were not heroes.

We just did our jobs by the book.

But sometimes doing your job right is enough.

I hope they made it home.

I hope they lived.

I hope someday they know we were not monsters, just men doing our duty.

The words would reach the women 50 years later.

But in June of 1945, they knew nothing of this.

They only knew they were going home.

The journey back across the Atlantic took two weeks.

Slower ships crowded with repatriated prisoners, supplies, personnel.

The women stood on deck when the ship entered European waters.

Gray sky, cold wind, the coastline of a continent in ruins.

This was home.

This was what they had fought for.

Rubble and ash and defeat.

They landed in France were processed through Allied checkpoints loaded onto trains heading into occupied Germany.

As the train rolled through the countryside, they saw the devastation.

Cities bombed flat, bridges destroyed, factories skeletal, refugees walking along roads with everything they owned on their backs.

Children with hollow eyes, old people sitting in the ruins of their homes staring at nothing.

Anna pressed her face to the window.

She had known intellectually that Germany lost.

But seeing it was different.

This was total, complete.

The country she left no longer existed.

What remained was something new, something broken, something that would have to be rebuilt from nothing.

The train reached Bavaria in early July.

Anna disembarked at a station that was half collapsed.

She walked through streets she had known since childhood.

Every third building was destroyed.

Some just gone empty spaces where homes had stood.

Others damaged walls standing, but roofs missing windows, empty black holes.

The church where bells had rung every Sunday was a shell.

The market square was a crater.

She found her family home.

The roof was damaged, windows broken, but the walls stood.

She knocked on the door, waited, heard footsteps inside, the door open.

Her mother stood there, older, thinner, gray hair where Brown had been.

She stared at Anna for a long moment, then pulled her inside, held her sobbed against her shoulder.

When the crying stopped, her mother asked the question, “Did they hurt you?” “No, mama.” They gave me food and medicine, and sent me home.

Her mother stared trying to process this.

But we were told, I know what we were told.

It was all lies.

Her mother had no response.

The propaganda had been so complete, so consistent.

The idea that it was simply false was too large to grasp.

Anna lived with her mother in the damaged house.

They repaired what they could, scrged for food, stood in lines for rations.

The occupation government, American and British, provided basic supplies, more than Anna expected, less than what was needed.

Germany was being kept alive, but not comfortable.

Punishment and mercy mixed together.

In 1946, Anna found work as a translator for the American occupation forces.

The irony was not lost on her.

Former prisoner working for former capttors.

But the pay was steady and the Americans needed German speakers who could be trusted.

She translated documents, attended meetings, helped with civilian administration.

She was good at it, efficient.

The Americans appreciated efficiency.

One day in 1947, she was translating a document about denoxification proceedings, lists of party members, records of who had done what.

As she worked, she thought about the manifests Margaret had mentioned, the shipments that went to places that were not hospitals.

She thought about the young woman Petra, whose brother killed himself after seeing things he could not unsee.

She thought about all the pieces that were coming together into a picture no one wanted to look at.

She kept translating, kept working, but at night she wrote in her diary, working through the questions, the guilt, the complicity, the not knowing what you were part of until it was over.

She never published these entries.

Too raw, too personal.

But she kept them.

Evidence that someone had wrestled with these things.

The other women scattered across occupied Germany, each finding their way in the ruins.

Margaret Klein settled in Frankfurt.

She also became a translator, also worked for the occupation government.

She saw the same documents Anna saw, the records of camps, the testimony of survivors, the photographs, the evidence of systematic horror.

One afternoon in 1948, she sat in an office reading a report about supply chains to concentration camps.

She recognized some of the routing numbers.

She had processed those shipments, not knowing, not asking, just doing her job.

She walked out of the office and vomited in the street.

That night, she went home to her small apartment and made a decision.

She would testify at denoxification hearings.

At any forum that would listen, she would say, “I was part of it without knowing.

I processed documents.

I followed orders.

I did not ask questions.” That is how evil works.

through ordinary people doing their jobs without thinking.

She spent the next 30 years speaking.

Universities, schools, conferences.

Her message was always the same.

Systems matter.

I was part of an evil system.

But I also witnessed a good system saving my life.

Both lessons matter.

Evil can hide in bureaucracy, but good can be systematic, too.

We must choose which system we build.

Gerta Hoffman went to Hamburg.

Her health was broken.

Malnutrition and stress had taken years from her life.

She found work in a bakery kneading dough and tending ovens.

Simple work, quiet work.

She never married.

Everyone she might have loved was dead.

She lived alone in a small apartment and kept the blanket.

The greywill blanket Nurse Callahan had given her in Texas April 1945.

She used it every winter, repaired it when it frayed.

When people asked why she kept an old army blanket, she said simply, “It reminds me that humanity exists even when you do not expect it.” Gerta died in 1967 at age 50.

Her landlady cleaning out the apartment.

Found the blanket folded carefully at the foot of the bed.

Label still readable.

Property: US Army, Fort Hood, Texas.

Also found a small notebook with Gerta’s handwriting.

One entry dated May 1945.

Today I learned that rules can be mercy.

that the enemy of your nation is not always the enemy of your humanity.

The Americans did not save me because they love me.

They saved me because their rules said a prisoner is a human being.

That may be the greatest lesson I learned from war.

Systems matter.

Laws matter.

Protocol can be the difference between life and death.

Emma Roth became a school teacher in Munich.

She taught elementary school.

reading, writing, arithmetic, simple lessons for children who needed normaly.

She never told her students about the war.

But sometimes they asked about her hand, the three fingers, the scars.

She would say an accident a long time ago.

It was easier than explaining, easier than describing the cold and the fear.

And the moment when an American medic looked at her ruined fingers and said, “We will do what we can.

” They could not save all her fingers, but they saved her hand, her arm, her life.

That mattered more.

Emma never married.

The war had broken something in her that did not heal.

But she lived a useful life, taught hundreds of children, helped them learn to read and think and question.

Maybe that was her way of fighting back against propaganda, teaching children to think critically, to ask questions, to not believe everything they were told.

She died in 1989 just before the Berlin Wall fell.

She never saw Germany reunified, but she lived long enough to see the Federal Republic become prosperous and peaceful.

That was something.

Lisa Fischer returned to her parents’ farm in Bavaria.

Both her parents had survived a miracle in itself.

She helped with the farm work, learned to plow and plant and harvest.

In 1950, she married a neighbor’s son, a man named Verer, who had lost a leg at Anzio.

They understood each other’s silences.

They had four children, three sons, and a daughter.

They named the daughter Anna after Anna Weiss, who had held Lisa on the ship and told her it would be okay.

Lisa never forgot Texas, never forgot the medical tent, never forgot nurse Callahan humming amazing grace while she fought pneumonia.

In the 1980s, when her daughter asked about the war, Lisa finally told the story about being captured, about being terrified, about the inspection, about collapsing with pneumonia, about waking up to find an American nurse giving her medicine that saved her life.

Her daughter asked, “Why did they help you?” “You were the enemy,” Lisa answered.

“Because mercy does not ask whose side you are on.

It asks if you need help.” Ruth Werner reunited with her husband in October 1945.

He had been held in a P camp in France.

Treated well, fed adequately, given work on a farm.

He came home thinner but whole.

They held each other and cried and did not talk about the war for a long time.

When they finally did, they discovered they had the same story.

Captured, terrified, treated humanely, confused by the gap between propaganda and reality.

They never had children of their own.

Medical complications from malnutrition during the war.

But they fostered seven orphans over the years.

Children whose parents died in the war.

They gave these children a home.

Food, love, education.

When people asked why Ruth said, “Because I was shown mercy when I did not deserve it.

Now I pay it forward.” Ruth and her husband lived in Cologne.

They watched the city rebuild.

watched the cathedral, damaged but standing, become the symbol of survival.

They grew old together.

In 1994, Ruth’s husband died of a heart attack at age 74.

Ruth lived another 3 years.

In those final years, she spoke at schools about reconciliation.

Her message Germany did evil.

We must face that.

But in the midst of evil, we were shown that another way is possible.

Rules based on human dignity save lives.

She died in her sleep in 1997, age 79.

And Anna, Anna Weiss, lived the longest.

She married in 1952, a German engineer who had also been a prisoner of war, held in England.

They understood each other.

They had two daughters.

Anna worked as a translator until 1975, then retired.

She kept her diary, added to it over the years, reflections on what she had learned, what she had seen, what she had survived.

NI 50 years after the end of the war, a German American friendship organization organized a reunion event.

Former PS invited to meet former guards and staff.

The event was held in Texas near Fort Hood.

Anna received the invitation.

She was 73 years old.

Her husband had died 2 years earlier.

Her daughters encouraged her to go.

“It will bring closure,” they said.

Anna was not sure she wanted closure, but she went.

If you are watching this and thinking these stories matter, if you served during this era or your father did, I want to hear from you.

Drop a comment below.

Tell me what you think about the power of propaganda, about how [clears throat] systems based on human dignity make a difference, about whether we are teaching these lessons to young people today.

These stories need to be remembered, to be pileed down.

That is how we honor both the victims and the survivors.

Now, let me tell you about what happened when these women met their former captives 50 years later because what happened at that reunion will stay with you.

Five of the women attended, Anna, Margaret, Emma, Lisa, Ruth, Gerta was gone dead nearly 30 years, but the others came.

Elderly now, fragile but alive.

They toured the modern Fort Hood.

Massive base, tens of thousands of personnel, state-of-the-art facilities.

They tried to find where the old P camp had stood.

It was gone, paved over, new buildings erected.

No trace remained except in memory.

At the ceremony, they were introduced.

Former prisoners of war, survivors, witnesses to a moment when systems worked the way they were supposed to.

There were speeches, official words about friendship and reconciliation and shared values.

The women sat politely and listened.

But the speeches were not why they came.

They came because they heard that some of the former staff would be there.

And they wanted to say thank you.

A simple thing, but necessary.

Nurse Mary Callahan attended.

She was 82 years old, retired, living in Boston.

When the invitation came, her first instinct was to decline.

She was old.

Travel was hard.

And what was there to say after 50 years? But her daughter convinced her.

Mom, you always wondered if any of them survived.

Now you can know.

So she came.

The recognition happened slowly.

Anna saw her first.

White hair where Auburn had been, face lined with age.

But the eyes were the same.

Kind eyes.

Anna approached.

You were the nurse.

Callahan studied her.

I was many camps though.

Which one? April 1945.

The inspection.

You buttoned my coat when I could not.

Memory clicked into place for Callahan.

I remember you were all terrified.

I did not understand why at first.

Emma stepped forward, held up her right hand.

Three fingers.

You held my other hand during the amputation.

You hummed.

I never knew what song.

Callahan stared at the hand, then at Emma’s face.

It was Amazing Grace.

I always hum that one during procedures.

Help me stay calm.

Silence.

The other women gathered.

Five elderly German women and one elderly American nurse standing in Texas 50 years after the war.

Connected by memory of terror and mercy.

Callahan spoke voice trembling.

I need you to know something.

We did not think we were being heroes.

We were following protocol.

Geneva Convention Medical Ethics basic procedure.

We did not understand why you were so shocked that we treated you humanely.

We just did our jobs.

Anna responded, “And this was the thesis, the lesson, the meaning of everything.

” Because we had been taught you were monsters for years.

Every poster, every broadcast, we expected horror.

You gave us medicine and blankets and bacon for breakfast.

You did not save us because you were kind.

You saved us because your system said we were human beings.

Even though we were enemies, that is not just kindness.

That is civilization.

That is what we lost and you kept.

Callahan started crying.

I am old now, 82.

I have spent 50 years wondering if any of it mattered.

If anyone remembered.

Lisa spoke.

I am alive because you gave me penicellin.

I have four children, nine grandchildren.

An entire family exists because you followed protocol.

Because you did your job right, Ruth added.

My husband and I fostered seven orphans after the war.

We did it because we were shown mercy we did not deserve.

Because Americans followed rules that said even enemies are human.

We tried to pay that forward.

Callahan broke down.

The women embraced her.

Former enemy and captor united by shared memory of humanity preserved in darkest time.

They stood like that for a long time, crying, holding each other.

Five old women and a nurse who had simply done her job and never knew it mattered.

The reunion made news.

Small stories in German and American papers, human interest pieces.

But the real story, the lesson that mattered, that was what these women would spend their final years trying to teach.

Anna published her diary in 1997 titled Open Your Coat, a German woman’s story of American captivity.

It became required reading in some German schools.

Not a bestseller, but steady sales.

Translated into English in 1999.

Used in university courses about propaganda, about systems, about the power of rules to create mercy when individuals might choose hatred.

Margaret gave lectures until she was too frail to travel.

Universities invited her.

Historical societies, veterans groups.

She told the same story every time, refined over decades into its essential truth.

I was part of an evil system without knowing it.

I processed documents.

I followed orders.

I did not ask questions.

But I also witnessed a good system saving my life.

Both lessons matter.

We must choose carefully which systems we build because systems have power beyond individual choice.

Emma spoke at teacher conferences.

her message.

I teach children to question, to think critically, to remember that fear is a weapon used to control.

I almost died because I believed propaganda.

I lived because Americans followed rules.

Both facts shaped who I became.

Teach her students to question everything, especially the things that make them afraid.

Lisa gave interviews in her final years.

Cancer diagnosis in 1998.

Knew she had limited time.

spent it telling her story, newspapers, historians, students writing thesis, anyone who would listen.

Her final interview was in 2002, age 76, one year before her death.

The interviewer asked, “What do you want people to remember about your story?” Lisa answered, “That mercy is possible even in wars darkness, that rules based on human dignity save lives.

That propaganda is poison.

that even enemies can become witnesses to each other’s humanity.

I was 19 years old dying of pneumonia in an enemy camp in a foreign country.

And they saved me.

Not because they liked me, not because I deserved it.

Because their system said every human being matters.