August 22nd, 1945.

Camp McCoy, Wisconsin.

in the morning.

Steam rose from the Messaul kitchen in thick white clouds that hung in the pre-dawn air like ghosts.

The smell came first.

Salt and smoke and something primal that cut through the cold Wisconsin morning and reached deep into the bones of every man who’d ever known hunger.

Bacon, 20 lbs of it, sizzling on a griddle the size of a dining room table.

Corporal Danny Martinez stood over that griddle with a spatula in his hand and sweat running down his face despite the autumn chill.

He was 20 years old, built like a fence post with the kind of permanent tan that came from growing up on a Texas ranch where the sun never stopped and the work never ended.

He’d been flipping bacon since that morning.

His wrist achd, his eyes burned from the smoke, but he kept flipping because Captain Harrison had given him an order and Danny Martinez didn’t question orders.

The bacon hissed and popped.

Fat rendered into liquid gold that pulled at the edges of the griddle.

The strips curled and crisp, turning from pale pink to deep amber to the kind of brown that made a man’s mouth water without permission.

Martinez watched each piece like a hawk.

Too pale and it would be chewy.

Too dark and it would taste like charcoal.

His daddy had taught him that back home cooking for the ranch hands during roundup.

Get the bacon right and men would forgive almost anything else on the plate.

get it wrong and they’d remember forever.

Behind them, massive pots of scrambled eggs bubbled on the stove.

Biscuits rose in industrial ovens, their tops turning golden, their insides staying soft and layered like clouds.

Gravy simmerred in a pot so large Martinez could have bathed in it.

Coffee percolated in three different urns, filling the kitchen with a smell that was somehow both bitter and comforting at the same time.

Martinez had cooked breakfast for soldiers before.

He’d done it a hundred times since shipping out two years ago.

But this morning felt different.

This morning, the food wasn’t for American boys who’d grown up eating bacon for breakfast and thought nothing of it.

This morning, the food was for 300 Japanese women who were supposed to arrive at camp within the hour.

Prisoners of war, the enemy, women who’d served an empire that had bombed Pearl Harbor and tortured American soldiers and fought with a fanaticism that still gave Martinez nightmares.

He thought about his cousin Ricky who died at Baton.

The stories that came back from survivors of the death march made Martinez want to put his fist through a wall.

Japanese soldiers had starved American prisoners, beaten them, work them to death in the tropical heat.

And now here he was cooking bacon for Japanese prisoners.

Real bacon.

The good stuff.

Four strips per woman, plus eggs and biscuits and gravy and coffee with real cream.

It didn’t sit right, but orders were orders.

The kitchen door swung open.

Captain William Harrison stepped inside, bringing a gust of cold air with him.

He was 35, though the war had aged him in ways that couldn’t be measured in years.

His uniform was crisp despite the early hour.

His boots were polished to a mirror shine, but his eyes carried a weight that no amount of sleep would ever lift.

Harrison had lost his best friend three months ago.

Lieutenant Tom Chen, a Japanese American who died proving his loyalty on a volcanic rock in the middle of the Pacific.

Tom had taken a bullet meant for Harrison at Eoima, had died with his hand pressed to a wound that wouldn’t stop bleeding, had looked up at Harrison and said four words that Harrison heard every single night in his dreams.

Make it mean something, Bill.

Harrison walked to the griddle and I stood beside Martinez, watching the bacon sizzle.

Neither man spoke for a long moment.

The only sounds were the hiss of cooking meat and the rumble of coffee percolating and the distant clank of meshaul workers setting up tables in the dining area.

How much bacon is that, Corporal? Harrison finally asked.

20 lb, sir.

Maybe 22.

And you’ve been at it since when? 0430, sir.

Harrison nodded slowly.

His jaw was tight.

His hands were clasped behind his back in that way officers had when they were working through something difficult and didn’t want anyone to see their fist clench.

“You know what we’re doing today,” Harrison said.

It wasn’t a question.

“Yes, sir.

Feeding prisoners, sir.” “Japanese prisoners.” “Yes, sir.” Another silence.

Martinez flipped a row of bacon.

The strips crackled and spat.

My cousin died at Batan, sir.

Martinez said quietly.

They starved him, beat him.

He weighed 90 lb when he died.

90 lb.

Martinez’s voice cracked just slightly.

And now I’m cooking bacon for them.

Harrison turned to look at the young corporal.

Really look at him.

Martinez kept his eyes on the griddle, but his shoulders were tense and his jaw was working like he was chewing on words he couldn’t quite spit out.

I know about your cousin, Harrison said.

And I’m sorry, truly, but here’s what you need to understand, Corporal.

Those women arriving today didn’t kill your cousin.

They [clears throat] didn’t torture our boys.

They’re not soldiers.

They’re nurses and radio operators and students who got caught up in something bigger than themselves.

Sir, they still serve Japan.

They did, and we still won, which means we get to decide what kind of victors we want to be.

Harrison paused, letting that sink in.

The Japanese army starved our prisoners because they were cruel.

We’re going to feed theirs because we’re Americans.

You understand the difference? Martinez nodded, but his face showed he was still wrestling with it.

Harrison put a hand on the young man’s shoulder.

Your daddy raised you right, didn’t he? Taught you how to treat people.

Yes, sir.

He always said any man can hurt someone weaker.

Takes real strength to show mercy when you got the upper hand.

Smart man, your father.

He’s right.

And that’s what we’re doing today.

We’re showing these women what American strength really looks like.

Not cruelty, not revenge, just basic human decency.

That’s our weapon now.

Kindness.

Martinez flipped another row of bacon.

Some of the tension left his shoulders.

Besides, Harrison added, his voice dropping lower.

Wait until you see them.

Then tell me if you still think they’re the enemy.

At exactly , the buses rolled through the front gate of Camp McCoy.

There were six of them painted olive drab, kicking up dust from the gravel road.

They moved slowly like herses in a funeral procession.

When they stopped in front of the administration building, their engines idling, there was a moment of absolute stillness.

Even the wind seemed to hold its breath.

The first woman off the first bus moved like she was stepping onto a scaffold.

Her name was Rachel Yamada, though Harrison didn’t know that yet.

All he knew was that she was 22 years old according to the manifest a nurse from Hiroshima and she weighed 92 lb.

He could see every one of those 92 lbs in the way her uniform hung on her frame like laundry on a line.

Her face was hollow.

Her eyes were huge and dark and filled with something Harrison recognized from too many battlefields.

Not just fear, resignation.

The look of someone who’d already decided they were dead and was just waiting for the universe to catch up.

Behind Rachel came 299 more women.

Each one stepping off those buses like they were walking into their own execution.

Their movements were careful, measured robotic.

They didn’t speak.

They barely breathed.

They formed lines without being told, standing in perfect rows with their hands at their sides and their eyes fixed on nothing.

Sergeant Ruth Coleman stood beside Harrison clipboard in hand, watching the women assemble.

She was 28, a nurse from California, with blonde hair pulled back in a regulation bun and a face that had seen enough war to know pity when it showed up.

She made a small sound in the back of her throat.

“Not quite a gasp, more like someone had punched all the air out of her lungs.” “Jesus Christ,” she whispered.

“Language sergeant,” Harrison said automatically, but his voice had no force behind it.

He was staring at the women with the same horrified fascination.

They were skeletons dressed in cloth.

Every single one of them.

Not thin, not slender, skeletal.

Their cheekbones jutted like blades.

Their wrists were twigs.

Their ankles looked like they might snap under their own weight.

The September sun was warm, but every woman shivered like it was January.

Coleman scanned her clipboard, reading medical notes from the processing center in San Francisco.

Her voice was tight.

Average weight 90 lbs.

Malnutrition across the board, vitamin deficiencies, parasites.

Scurvy in some cases.

Scurvy, sir, this isn’t 1750.

Harrison said nothing.

He was watching a young woman near the back of the formation.

She couldn’t have been more than 20.

A student according to her papers.

Hannah, is she da? She swayed slightly, then caught herself, locked her knees, forced herself to stand straight.

Pride Harrison realized even starving even defeated these women had pride.

It made his hatred harder to hold on to.

Beside the students stood the radio operators.

One of them, a woman named Ko Sato, kept her eyes fixed on the ground like she was afraid to look up and see what fresh hell awaited her.

She was 25, had broadcast enemy propaganda for 18 months, had told millions of Japanese listeners that America was starving and collapsing and desperate.

Now she stood in an American prison camp, shivering in the Wisconsin sun, waiting to discover if the lies she told were actually true.

Harrison stepped forward, his boots crunched on gravel.

The sound made several women flinch.

He addressed them in English, knowing a translator would repeat his words in Japanese, his voice carried across the assembly area, formal and precise.

I am Captain William Harrison, commanding officer of Camp McCoy Prisoner of War Facility.

You are now prisoners of the United States Army under the protection of the Geneva Convention.

You will be treated in accordance with international law.

You will be housed in barracks with heat and running water.

You will receive three meals daily.

You will be provided medical care.

You will be treated with dignity.

He paused watching the translator work.

Most of the women’s faces showed nothing, but a few registered confusion.

Dignity.

Medical care.

Three meals.

The translator must have made a mistake.

Harrison continued, “You are not civilians.

You are military personnel taken as prisoners of war.

That means you have rights.

Those rights will be respected.

This is the American way.” He let that hang in the air for a moment.

The American way.

Like that meant something.

Like that was supposed to reassure women who’d been told for years that Americans were barbarians.

You will now be escorted to your barracks.

After you are settled, breakfast will be served in the mess hall.

That is all.

” Harrison stepped back.

Coleman gave orders and the guards began moving the women toward the housing area.

They walked in silence, still in formation, still moving like the condemned.

Martinez appeared at Harrison’s elbow, wiping his hands on his apron.

He’d come out to see the arrival.

Now he stood staring at the departing women, his face pale.

“Sir,” he said quietly.

I take it back what I said earlier about not wanting to feed them.

Why is that, Corporal? Because, sir, them women look like they ain’t been fed in about 6 months, and I was raised better than to let anyone starve, even the enemy.

Harrison nodded.

Good man.

Now get back to that kitchen.

Those eggs are probably burning.

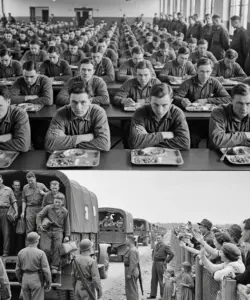

The women had been at camp for exactly 47 minutes when they filed into the messaul for breakfast.

They moved in the same careful formation, the same robotic precision.

They found seats at long tables, 20 women per table, and sat with their backs straight and their hands folded and their eyes on the table surface waiting.

The smell hit them first.

Bacon, coffee, fresh bread.

The scent was so rich, so overwhelming that some of the women’s eyes went wide.

Others closed their eyes and breathed in deep like drowning people catching a gasp of air.

Then the food arrived.

Martinez and three other servers moved through the mess hall carrying trays.

They placed them on each table with practiced efficiency.

Metal plates, real silverware, and on each plate more food than most of these women had seen in months.

Four strips of bacon, crispy and glistening with rendered fat.

Three scrambled eggs, bright yellow and fluffy, still steaming.

Two biscuits golden on top and soft inside with ps of real butter already melting into them.

A ladle of gravy thick and creamy and flecked with black pepper.

A cup of coffee black with small containers of cream and sugar on the side.

The women stared at the plates like they were looking at a mirage in the desert.

Nobody moved.

Nobody reached for a fork.

Nobody touched anything.

300 women sat frozen, staring at food that couldn’t possibly be real.

Rachel sat at a table near the front, her eyes locked on the bacon.

She’d seen bacon before, of course, before the war.

But that had been years ago.

The strips on her plate were nothing like the thin, pale pieces she remembered from childhood.

These were thick, dark.

The fat had crisped into lacy edges that caught the overhead lights.

Oil beat it on the surface.

The smell alone made her mouth water so intensely she had to swallow.

But it had to be poison or a trick or some kind of psychological warfare.

Feed the prisoners once, let them taste real food, then take it away and watch them suffer.

That made sense.

That was logical.

The Americans were cruel and savage.

Everyone knew that.

The radio had said so.

The newspapers had said so.

Her commanding officers had said so.

So why did the bacon smell so good? at the table behind Rachel Kiko.

Kiko Sada was doing calculations in her head.

She’d studied engineering before the war.

She knew ratios and production numbers.

Four strips of bacon per woman, 300 women.

That was 1,200 strips of bacon.

At least 20 lb of meat for one meal for prisoners.

She’d broadcast reports for months about American food shortages, rationing, desperation, empty grocery stores, housewives lining up for scraps.

But if America was rationing food, if they were running out, if they were desperate like the radio scripts had claimed, then why were they feeding enemy prisoners bacon? The math didn’t work.

Something was wrong.

Either the broadcast had been lies or this meal was theater.

One or the other.

Both couldn’t be true.

Hannah Esshida, the youngest at the table, stared at the biscuits.

She’d grown up in a village where bread was a luxury.

Rice was everything.

But these Americans served bread like it cost nothing.

Two biscuits per prisoner.

Soft bread, white bread with butter.

Her stomach cramped so hard she had to put a hand against it.

She couldn’t remember the last time she’d eaten bread.

March, February, the months blurred together into one long gray hunger.

At a table on the far side of the room, Emma Watanabe studied the eggs.

Real eggs, not the powdered substitute that had been standard rations for the past year.

These were actual eggs from actual chickens.

Three of them, bright yellow, fluffy from being scrambled with cream.

She could see tiny flexcks of butter mixed in.

Emma came from a farming village.

She knew what eggs cost.

She knew what it took to keep chickens fed and healthy and laying.

And here was America serving three eggs per prisoner.

Not one.

Three.

Like eggs were nothing.

Like they had so many eggs they could afford to waste them on defeated enemies.

Martinez moved between tables, checking on the women, making sure everyone had been served.

He stopped at Rachel’s table and noticed that nobody had touched their food.

Every plate sat untouched.

Every fork lay exactly where it had been placed.

“Ma’am,” he said to Rachel in English.

She didn’t look up.

Ma’am, [clears throat] you can eat.

It’s okay.

It’s safe.

Rachel didn’t respond.

Couldn’t respond.

Her throat had closed up.

Martinez looked around confused.

He caught Coleman’s eye across the room and shrugged helplessly.

Coleman made her way over.

They think it’s poisoned, she said quietly to Martinez.

Or a trick.

Can you blame them? But it’s just breakfast, Sarge.

To you.

To them.

This might be more food than they’ve seen in months.

She raised her voice slightly, addressing the women at Rachel’s table through the translator.

The food is safe.

You can eat.

You need to eat.

Still nothing.

300 women sat motionless in front of 300 plates of cooling food.

Then Ko Sato reached out one trembling hand.

Her fingers were thin as pencils.

Her nails were ragged.

She picked up a single strip of bacon and held it in front of her face, studying it like a scientist examining a specimen.

The bacon was still warm.

The fat had congealed slightly, turning the strip firm and crispy.

She could see the grain of the meat, the rendering of the fat, the caramelization of the sugars.

This was real.

This was actual food, not a photograph, not propaganda.

Real.

She brought the bacon to her lips, took a small bite, just the corner, just enough to taste.

Salt exploded across her tongue, then smoke, then the rich, almost overwhelming flavor of pork fat, of protein, of actual meat.

Her body reacted before her mind could catch up.

Saliva flooded her mouth.

Her stomach clenched and unclenched.

Every cell in her body suddenly screamed for more.

She took another bite, bigger.

The bacon crunched between her teeth.

Fat coated her mouth.

She chewed fast, swallowed hard, and before she knew what she was doing, she’d eaten the entire strip.

Then she reached for another, and another.

Her hands were shaking.

Tears were streaming down her face, but she couldn’t stop eating.

The bacon disappeared, then the eggs, then the biscuits.

She tore into the food with both hands, abandoning the four, cramming scrambled eggs into her mouth, biting into biscuits without bothering to butter them, gulping coffee that burned her tongue.

But she didn’t care because it was real and it was here and it was food.

Her breakdown shattered the silence like a gunshot.

All around the messaul, 300 women lunged for their plates.

The sound was like nothing Harrison had ever heard.

Not quite crying, not quite screaming.

Something animal and desperate and heartbreaking.

Forks scraped against metal.

Women chewed with their mouths open because they had forgotten how to do anything else.

Some were crying while they ate.

Others made small sounds in the backs of their throats.

Gratitude or grief or some combination of both.

Rachel bit into her first strip of bacon and the world tilted sideways.

The salt hit her bloodstream like a drug.

The protein, the fat, the actual sustenance of it crashed through her system and woke up parts of her body that had been shutting down for months.

She could feel it happening.

Could feel her metabolism kick back into gear.

Could feel her brain clear just slightly like fog burning off in sunlight.

She thought about her little brother back home, 8 years old, 4t tall, legs like sticks, because there he was never enough food, and what food there was went to the soldiers first.

She thought about how this single strip of bacon, this one piece of meat that the Americans fed to prisoners, without a second thought, contained more protein than her brother ate in a week.

And she understood in that moment in a way that made her want to scream that everything she’d been told was a lie.

Martinez stood frozen near the kitchen door, watching 300 starving women devour breakfast like their lives depended on it.

Because their lives did depend on it.

He could see it in their faces, in the desperate way they ate, in the tears streaming down their cheeks.

“Sarge,” he said to Coleman, his voice barely a whisper.

“What the hell did their government do to them?” Coleman was wiping her own eyes, starved them, lied to them, and called it patriotism.

Harrison watched from the back of the messaul.

He’d seen a lot in this war, had seen men die in a thousand different ways.

Had held Tom Chen while he bled out on black volcanic sand.

had watched ships sink and planes fall and cities burn.

But somehow watching 300 enemy prisoners cry while they ate bacon was what finally broke something inside him.

These weren’t enemies.

They were victims.

And the real enemy, the one that had done this to them, was sitting in Tokyo still telling lies.

He made a decision in that moment.

These women would go home eventually, but when they did, they’d go home knowing the truth.

They’d go home having seen what America really was.

Not the caricature their propaganda had painted, the real thing.

The abundance, the waste, the casual, almost careless generosity of a nation so rich it could afford to feed its enemies like honored guests.

That would be his revenge, not cruelty.

Truth.

The meal lasted 20 minutes.

When it was over, every plate was clean.

Not just clean, scraped.

Women had used their fingers to get every last bit of gravy, every crumb of biscuit.

The coffee were gone.

The cream was gone.

Even the sugar packets had been emptied.

And then, as the reality of what had just happened began to sink in, the women started to talk.

Quiet at first, whispers in Japanese that the guards couldn’t understand, but didn’t need to.

The tone was enough.

Confusion, disbelief, the first fragile shoots of a question that would grow into something much larger.

If America was this strong, this rich, this careless with food, then what else had been a lie? The second day began the same way the first had ended, with food.

Too much food.

Food that kept coming no matter how many times the women expected it to stop.

Breakfast arrived at .

Pancakes this time stacked three high on each plate with butter melting between the layers and maple syrup in glass pictures on every table.

Sausage links, six per woman, glistening with grease.

Hash browns, crispy on the outside and soft inside.

Orange juice, coffee, milk.

Rachel sat at the same table as the day before and stared at her plate with something approaching horror.

Yesterday had been a test, she’d decided, or a psychological trick.

Feed them once, show them abundance, then take it away and watch them break.

That made sense.

That was strategy.

But here was day two and the food was back and it was just as excessive as before.

She looked around the messaul.

Every table was the same.

Every woman had the same heaping plate.

Nobody was getting less.

Nobody was being singled out.

This was standard.

This was normal.

For the Americans, this breakfast of pancakes and sausage and juice was just another Tuesday morning.

The math was starting to become undeniable.

Ko ate slowly, this time, forcing herself to chew properly to taste instead of just consume.

[snorts] The pancakes were sweet and fluffy.

The syrup was real maple, not the corn syrup substitute she’d known before the war.

The sausage had actual meat in it, not filler or sawdust or whatever the Japanese military had been mixing into rations for the past 3 years.

She counted while she ate six sausages per woman, 300 women, 1,800 sausages for one breakfast.

That was at least 400 lb of pork for prisoners, for the enemy.

She’d broadcast numbers for 18 months.

Production figures, casualty reports, strategic assessments, all of them lies she now suspected.

But she was good with numbers.

She trusted numbers.

And the numbers here were screaming at her.

If America could feed enemy prisoners 400 lb of pork for breakfast, how much pork did they have for their own soldiers, for their civilians? The rationing broadcast she’d read, the ones about American housewives lining up for scraps, about grocery stores with empty shelves, about children going hungry while their fathers fought overseas.

All lies.

Her hand shook slightly as she cut another piece of sausage.

At the table behind her, Hannah poured syrup over her pancakes and watched it cascade down the sides, pooling on the plate in a golden amber lake.

She’d never seen this much sugar in one place.

In Japan, sugar had disappeared from civilian markets in 1943.

What little remained went to the military.

And even then, it was rationed, carefully, measured out in tiny quantities that had to last.

Here, the Americans had pictures of syrup on every table.

Pictures.

Full pitchers.

And when a pitcher ran low, a server would appear and replace it without being asked.

The abundance was casual, thoughtless, like air or water or anything else that existed in such quantity that worrying about it seemed absurd.

Hannah ate her pancakes and felt something crumbling inside her, not her body.

Her body was getting stronger with every meal.

She could feel it.

Could feel her hands steadying her vision, clearing her mind, sharpening as actual nutrition hit her bloodstream.

No, what was crumbling was something else.

The foundation she’d built her entire adult life on.

The certainty that Japan was strong and [clears throat] America was weak.

That sacrifice and suffering were noble because everyone was suffering together.

That the war was righteous because the alternative was surrendering to barbarians.

But barbarians didn’t serve pancakes with real maple syrup to their prisoners.

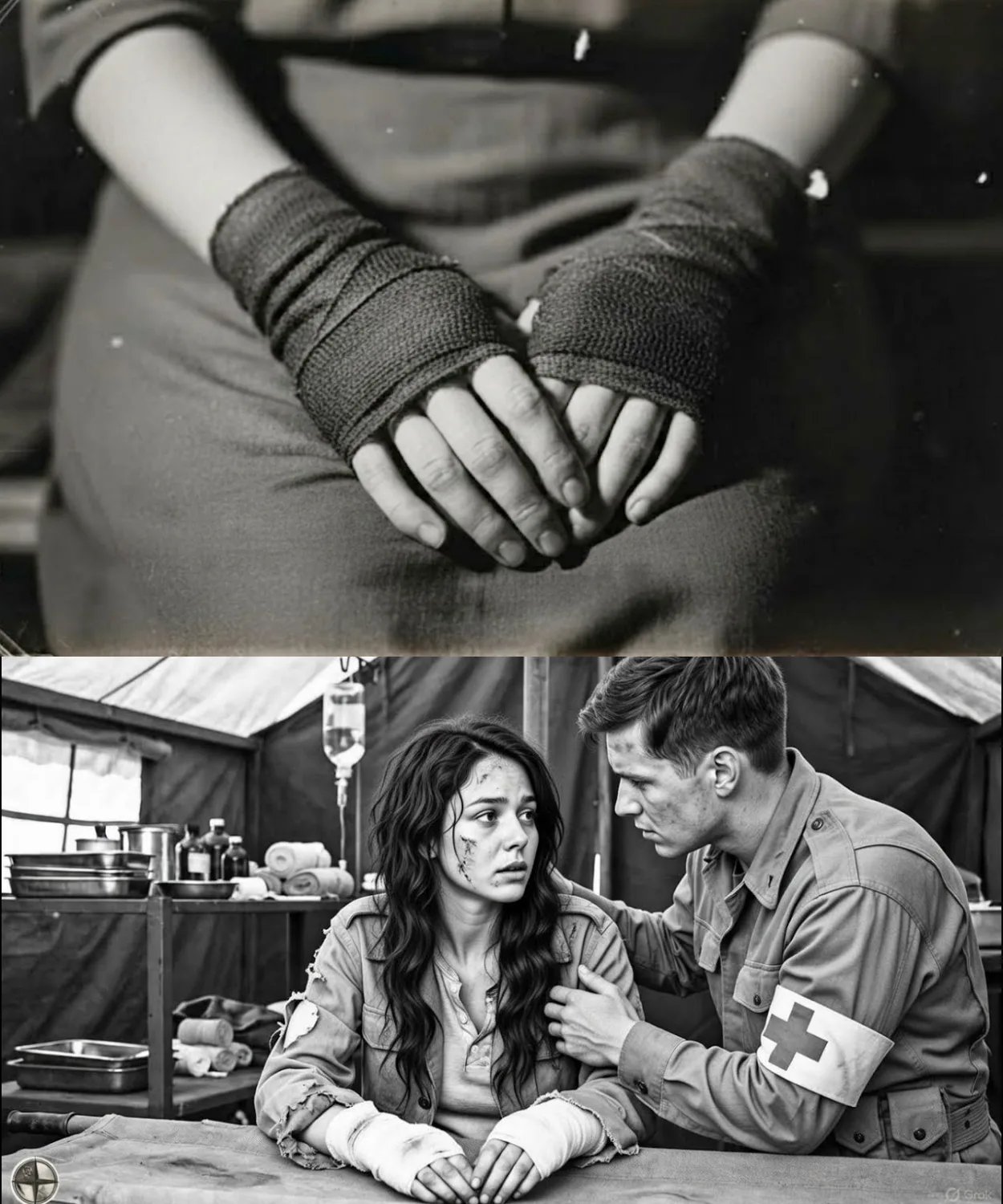

After breakfast, the women were escorted to the camp infirmary for medical examinations.

It was mandatory, Coleman explained through the translator.

Standard procedure for all prisoners of war.

Health screenings to check for contagious diseases, parasites, malnutrition, injuries that needed treatment.

The infirmary was a long, low building that smelled of disinfectant, and something else.

Something clean and medicinal and utterly foreign.

Rachel recognized it after a moment.

antibiotics, real antibiotics, penicellin and sulfa drugs and all the medications that had disappeared from Japanese field hospitals years ago.

American doctors moved through the building in clean white coats, their hands scrubbed, their instruments sterilized.

Nurses with clipboards recorded information in neat handwriting.

Everything was organized, efficient, professional.

Rachel was examined by a doctor who looked younger than she was.

He had gentle hands and a face that showed concern but not pity.

He measured her height and weight.

Checked her blood pressure, listened to her heart and lungs.

He examined her hands, her feet, her teeth.

He drew blood with a needle so fine she barely felt it.

He asked questions through the translator.

When was your last menstrual period? Do you have pain anywhere? Difficulty breathing dizziness? She answered mechanically, still not quite believing this was real.

The doctor studied her chart, made some notes, then looked at her with an expression she couldn’t quite read.

“You were a nurse,” he said through the translator.

“It wasn’t a question.

He’d seen it in her file.” Rachel nodded.

“Did you know you have scurvy?” The word hit her like a slap.

“Scurvy, a disease from centuries ago, a disease from sailing ships and long voyages and diets with no fresh fruit or vegetables.

Not a disease from the 20th century.

Not a disease from modern warfare, but apparently yes, she had scurvy.

Also, severe vitamin D deficiency, the doctor continued.

Anemia, probable parasites were waiting on the lab results.

Malnutrition across the board, he paused.

Your body was cannibalizing itself.

Another month or two and you would have started losing teeth.

Maybe vision.

Definitely bone density.

Rachel stared at him.

Through the translator, she asked the only question that mattered.

Did I feel sick because I was dying? Or did I not feel sick because I was used to it? The doctor’s expression softened.

The latter.

You’ve been starving for so long that starvation felt normal to you.

At the examination table next to Rachel’s, Emma was getting similar news.

91 lb, 5’3, underweight by at least 40 lb.

Vitamin deficiencies, parasites, dental decay from malnutrition.

The American nurse examining her was tall and strong and healthy in a way that made Emma feel like a different species.

The nurse’s skin glowed.

Her eyes were clear.

Her hands were steady and sure.

She looked like she’d never missed a meal in her life.

This kind of malnutrition would be child abuse back home, the nurse said to a colleague, not realizing Emma could hear.

Or maybe not caring.

These women’s bodies are shutting down and they don’t even know it.

Emma wanted to laugh or cry or both.

Child abuse.

In Japan, everyone looked like this.

Every civilian, every soldier who wasn’t in a command position.

Every woman and child an elderly person.

This was normal.

This was life.

This was what sacrifice looked like.

Except it wasn’t sacrifice if the people asking you to sacrifice were lying about why.

The medical examinations took 3 hours.

When they were finished, every woman had been weighed, measured, documented, and diagnosed with some combination of malnutrition, vitamin deficiency, and parasitic infection.

The average weight was 90 lb.

The average deficit was 30 to 40 lb.

Every single woman was malnourished.

Every single one.

Coleman compiled the results and brought them to Harrison’s office.

She dropped the clipboard on his desk with more force than strictly necessary.

90 pounds, she said without preamble.

Average weight 90 pounds, some as low as 82.

Captain, these women are walking skeletons.

Harrison picked up the clipboard and scanned the numbers.

His jaw tightened.

Scurvy, Coleman continued.

In 1945, we’ve got women with scurvy and they don’t even know they’re sick because they’ve been starving for so long it feels normal.

Recommendations: double rations for the first month, minimum, maybe longer.

vitamin supplements, deworming medications, dental care for about 90% of them.

Coleman’s voice was tight with anger.

Sir, their own government did this to them.

While telling them America was starving.

Harrison sat down the clipboard and leaned back in his chair.

He thought about Tom Chen, about the men who died at Eoima believing they were fighting for something righteous.

About the propaganda that had convinced an entire nation that suffering was noble and victory was inevitable.

Approve the double rations, he said.

And the vitamin supplements.

File the request today.

I want it approved by end of week.

Yes, sir.

And Sergeant, make sure these women understand where this food is coming from.

Make sure they know we’re not rationing, that we’re not running low, that we have so much food we’re sending surplus to Europe.

I want them to see the abundance.

All of it.

Coleman studied him for a moment.

Sir, that might break them.

Good.

Let it break them.

Better they break here with the truth than go home still believing lies.

The third night, someone smuggled a newspaper into the barracks.

It was a San Francisco chronicle from a week earlier, left behind by a careless guard.

Or maybe not so careless.

The pages were wrinkled and the ink was smudged, but the headlines were clear enough.

Labor strikes spread across industrial Midwest.

Workers demand higher wages.

Surplus grain shipments to Europe continue.

Warehouses report storage problems.

Factory production hits record levels.

Postwar economy stronger than expected.

The newspaper passed from hand to hand through the barracks like contraband, which technically it was, but the guards who saw it being passed chose to look the other way.

Maybe on Harrison’s orders, maybe on their own.

Either way, 300 women read American News for the first time in years.

Emma read it by flashlight under her blanket, translating for the women around her.

Her English was better than most.

She’d studied it in school before the war.

Labor strikes, she read aloud in Japanese.

Workers refusing to work until wages increase.

Factory production at record levels.

Surplus grain being sent to Europe because American warehouses are too full.

Silence in the dark barracks.

Surplus? Someone whispered, “They have surplus grain.

They’re sending it away because they have too much.

” “While we starved,” another voice added.

“While our children starved, they had so much they couldn’t store it all.” The anger started quietly, just whispers in the dark.

But it was anger nonetheless.

Real anger, hot and sharp, and directed at the right target for the first time.

Not at America, at Tokyo, at the generals and ministers and propaganda officers who’d lied, who’d sent women to war while telling them the enemy was weak, who’d starve their own people while claiming everyone was starving together.

Rachel lay on her bunk and stared at the ceiling.

She thought about the boys she’d nursed, the ones who died believing their sacrifice mattered, believing they were defending Japan from savages.

They died with honor in their hearts and lies in their heads, never knowing that the savages they feared threw food away because they had too much.

Every death after 1942 had been for nothing, worse than nothing, for lies.

She felt something hot and heavy building in her chest.

Not grief, not anymore.

Rage.

On the fifth day, they were allowed outside for recreation time.

The weather was cool but clear autumn in Wisconsin, settling in with that particular quality of light that made everything look sharp and defined.

The women filed into the recreation yard in their usual formation, still moving with military precision, despite days of being told they could relax.

The yard was bigger than Rachel had expected.

Maybe two acres surrounded by a low fence that was more psychological than practical.

Anyone who wanted to could probably climb it, but where would they go? They were in the middle of Wisconsin.

Most of them couldn’t speak English.

And more importantly, why would they run from a place that fed them three meals a day? The grass in the yard was real.

Not dirt, not gravel.

Grass, green, and soft and growing thick.

Rachel knelt down and touched it with her fingers.

The blades were cool and slightly damp from morning dew.

They smelled like earth and growth and life.

In every bombed city she’d served in the grass had died first.

Trampled by soldiers scorched by fire poisoned by ash.

The ground had turned to gray dust that got into everything.

Your clothes, your food, your lungs.

But here in an American prison camp, grass grew like it was the most natural thing in the world.

Hannah walked the perimeter of the yard, looking beyond the fence at the landscape.

Fields stretched to the horizon.

corn, she thought, or maybe wheat.

She didn’t know American crops well enough to tell from this distance.

But whatever it was, there were acres and acres of it, miles of it, food growing in quantities that made her head spin.

She thought about her village back home, about the tiny plots of land each family tended, about how a bad harvest could mean starvation, about how every grain of rice was precious counted rationed.

And here was America growing crops on a scale that seemed almost offensive in its excess.

Ko found a bench near the corner of the yard and sat down.

A guard was stationed nearby a young man who couldn’t have been more than 20.

He was reading a book.

Not watching the prisoners with suspicion or hostility.

Just reading.

Like he was bored.

Like guarding enemy prisoners was such a routine unthreatening task that he could afford to be distracted.

The guard noticed her looking and nodded politely.

Then he went back to his book.

Ko stared at him at his casual posture, his clean uniform, his new boots, his complete lack of concern.

This was a man who’d never known scarcity, never known fear, never known what it was like to wonder if tomorrow’s meal would come.

She hated him for about 5 seconds.

Then the hate collapsed into something more complicated.

Envy, maybe.

or grief for a life she’d never had and now never would.

That evening after dinner, Martinez was in the kitchen cleaning the griddle when Hannah appeared in the doorway.

She shouldn’t have been there.

Prisoners weren’t allowed in the kitchen, but she stood there anyway, thin and uncertain, holding something in her hands.

Martinez [clears throat] looked up from his work.

Ma’am, you’re not supposed to be in here.

Hannah didn’t speak English well, but she understood enough.

She held out what she was carrying.

It was an origami crane folded from a scrap of paper she must have found somewhere.

The folds were precise and delicate.

The paper bird looked almost alive.

“Thank you,” she said in heavily accented English.

“For food.” “Thank you.” Martinez stared at the crane, then at Hannah, then back at the crane.

His throat felt tight.

“Ma’am, I’m just following orders.

Just doing my job.” Hannah shook her head.

She didn’t have the English to explain what she meant.

that it wasn’t about orders or jobs.

That cooking real food with actual care was a kindness she hadn’t expected.

That the bacon had been cooked perfectly, not burnt or underdone, and that small detail had meant something to her.

Had reminded her that somewhere underneath all this, there were still people treating other people like human beings.

She set the crane on the counter and left before Martinez could respond.

He stood there for a long time looking at the paper bird.

Then he picked it up carefully and put it in his pocket.

When he got home on leave two months later, he would show it to his father.

His father would put it on a shelf in the living room and it would stay there for the next 40 years.

The library opened on day seven.

Harrison had requisitioned it personally, pulling strings and calling in favors to get approval.

The camp had a small building that had been used for storage.

He had it cleaned out, furnished with tables and chairs, and stocked with books.

English books, mostly since that’s what was available, but also newspapers, magazines, maps, anything with information.

Coleman made the announcement at breakfast.

As of today, you have access to the camp library.

It will be open every afternoon from 2 to 6.

You may read, study, or simply sit.

There are books on history, science, agriculture, medicine, also current newspapers and magazines.

The translator repeated the words in Japanese.

The women looked at each other in confusion.

A library for prisoners.

Rachel went that first afternoon more out of curiosity than anything else.

The building was small but well lit.

Books lined shelves along the walls.

Current newspapers sat on a rack by the door.

The room smelled like paper and ink.

Impossibility.

She gravitated toward the medical texts first.

Old habits.

She pulled a book on modern nursing techniques and sat down at a table near the window.

The text was in English, but her English was decent enough.

She could make out most of it.

Antibiotics, sterilization techniques, surgical sanitation, blood transfusions, all the procedures and medications that had been standard practice in American field hospitals.

while Japanese nurses made do with hot water and prayers.

She read about penicellin, about how it could cure infections that would otherwise be fatal, about how American factories produced it by the ton enough to supply the entire military and still have surplus for civilian use.

She thought about the men she’d watched die from infected wounds.

Men who could have been saved with a single shot of penicellin.

men who died because Japan didn’t have access to the drugs or the manufacturing capacity or the knowledge to produce them.

The book made it clear that this wasn’t classified information.

These techniques had been published, shared, available to anyone who wanted to learn them.

Japan could have had this knowledge, could have saved thousands of lives, but they’d been too proud to admit they needed help.

Too convinced of their own superiority to learn from others.

Rachel closed the book and pressed her forehead against its cover.

The grief was physical, a weight in her chest that made breathing difficult.

Emma found the agricultural section, books on farming techniques, crop rotation, fertilizer used mechanized equipment.

She opened one about American agriculture during the Great Depression, and read a sentence that made her stop breathing.

In 1933, the United States government began paying farmers to reduce crop production in order to raise prices.

She read it again and again, making sure she understood correctly.

America had paid farmers not to grow food.

Had deliberately reduced production because they were growing too much.

While half the world starved, America had crops rotting in fields because there was no market for them.

The scale of the abundance was almost obscene.

Hannah found a book about American universities.

She read about engineering programs, about women being admitted to technical fields, about scholarships and research grants and libraries full of resources.

She’d been pulled from her studies in her second year to serve the war effort.

Had been told that education could wait, that the nation needed her labor more than it needed her mind.

And here was America keeping universities running through the entire war, educating women in engineering while Japan sent theirs to factories.

Ko found the newspapers and read them cover to cover.

She read about labor strikes and factory production and housing shortages and all the mundane problems of a nation at peace.

She read letters to the editor complaining about taxes and traffic and the price of butter.

The price of butter.

People were writing angry letters about butter costing too much.

While in Japan, butter didn’t exist for civilians at any price.

The disconnect was so vast it felt like madness.

That night, the whispers in the barracks were different.

More focused, more angry.

The women had started comparing notes, sharing what they’d read, piecing together a picture of America that contradicted everything they’d been told.

“They published all of it,” Ko said to the group gathered around her bunk.

“The production numbers, the factory output, the agricultural data, it was all public information.

Anyone could have looked it up.” Which means our government knew, Emma added.

They knew how strong America was.

They knew we couldn’t win, and they sent us anyway.

While Hannah’s voice was small, young, still looking for a reason that would make sense, Rachel answered her voice hard.

Pride.

They’d rather kill us all than admit they were wrong.

The anger was spreading, turning from a simmer to a boil.

But it still had nowhere to go.

Not yet.

That would come later.

On day 10, the women were measured again.

Weight check required weekly.

Coleman explained Rachel stepped on the scale.

98 pounds.

She’d gained six pounds in 10 days.

Six pounds of actual body weight.

Not water retention or bloating, but muscle and fat and tissue rebuilding itself from the constant food around her.

Other women were getting similar results.

Hannah had gained 5 lbs.

Emma 7, Ko 5.

Their bodies were recovering faster than their minds.

Coleman reviewed the results with satisfaction.

Good.

You’re responding to the nutrition.

We’ll keep you on double rations for another month, then transition to standard portions.

Standard portions, which were still more food than any of them had seen in years.

That afternoon, a delivery truck arrived at camp.

The women watched from the recreation yard as guards unloaded crates.

So many crates.

Dozens of them, all marked with labels they couldn’t quite read from this distance.

Martinez appeared and started directing the unloading.

The crates went to the messaul storage.

More food.

Always more food.

One crate tipped and broke open.

Apples spilled onto the ground.

Red, shiny, perfect apples.

Dozens of them.

Martinez cursed and started picking them up.

A few had bruised in the fall.

He tossed those into a waste bin without hesitation.

Rachel watched him throw away perfectly good apples because they had small bruises.

apples that would have fed families, tossed in the trash like they were worthless.

She thought about her brother, about how an apple had been a luxury for him, a treat for special occasions.

And here was America throwing them away because they weren’t perfect enough.

The rage got hotter.

That night, Emma wrote in her journal by flashlight.

Her hands were steadier now.

Her handwriting was improving as her body got stronger.

Day 10, she wrote, “We’ve gained weight.

We’re getting healthier.

Our bodies are recovering.

But every meal feels like proof of a crime.

Every piece of fruit, every slice of bread, every cup of coffee is evidence that our government lied to us.

They told us America was weak.

They told us everyone was suffering.

They told us our sacrifice was necessary because we were all in this together.

But we weren’t all in this together.

They were sending us to do while knowing the enemy had so much food they threw it away.

I don’t know what to do with this anger.

I don’t know where to put it.

But I know I can’t forget.

I can’t go home and pretend I didn’t see this.

The truth is too big, too terrible, too important.

Someone has to tell it.

Someone has to make sure this never happens again.

She closed the journal and lay back on her bunk.

Around her, 300 women lay in their beds, awake and thinking, and slowly, inevitably, arriving at the same conclusion.

Everything had been a lie.

All of it.

And the people who told those lies had killed millions.

Not in combat, not in battle, but through deliberate, calculated deception that had sent people to dawn for a cause that was already lost.

That wasn’t war.

That was murder.

And somebody needed to pay for it.

Two weeks into their stay at Camp McCoy Major, Thomas Bradley arrived to give a lecture.

He was a logistics officer 40 years old with the kind of face that had seen too many spreadsheets and not enough sunlight.

He set up in the largest barracks arranged chairs and rows and waited while all 300 women filed in and took their seats.

Harrison stood at the back of the room, arms crossed, watching.

He knew what was coming.

He’d requested this lecture personally.

The women needed to see the numbers, needed to understand the mathematical impossibility of what their government had attempted.

truth delivered in cold, hard statistics that couldn’t be argued with or explained away.

Major Bradley didn’t waste time with pleasant trees.

He was a numbers man.

Numbers were what he knew.

He stood at the front of the room with a chalkboard behind him and began writing figures in neat columns.

Aircraft production, he said in his flat matterof fact voice.

The translator repeated his words in Japanese.

United States 1941 to 1945.

Total 96,000 aircraft, fighters, bombers, transports, reconnaissance 96,000.

He wrote the number on the board.

96,000.

Japan, same period.

28,000.

He wrote that number below the first 28,000.

The women stared at the board at the bun.

The gap between the numbers was enormous.

Impossible.

Bradley continued his voice, never changing tone, never adding emphasis or drama, just facts, just numbers.

Warships, United States 2,600, Japan 540.

More numbers on the board, the gap widening.

Oil production.

This is the important one.

United States 1.8 billion barrels.

Japan 33 million barrels.

He paused to let that sink in.

The translator repeated the figures slowly making sure every woman understood.

For every one barrel of oil Japan refined, the United States produced 54.

Ko sat in the third row and felt her engineering training kick in automatically.

She started doing calculations in her head.

Oil was everything.

You couldn’t run ships without oil.

Couldn’t fly planes.

Couldn’t move tanks or trucks or any mechanized equipment.

Modern warfare ran on petroleum.

If America was producing 54 times more oil than Japan, then the war had never been a contest.

It had been a mathematical certainty from the beginning.

Bradley moved on relentless.

Steel production.

Gary, Indiana, which many of you passed through on your train journey here, produced more steel in one year than Japan’s entire industry produced during the war.

Submarines.

Um, United States 288, Japan 56.

Merchant shipping.

Liberty ships alone, the United States produced over 2,000.

These were cargo vessels built so quickly that one shipyard was launching a new ship every day at peak production.

The numbers kept coming, each one a hammer blow.

Each one proof of something the women in that room were only beginning to understand.

This hadn’t been a war between equals.

This had been an industrial giant crushing a regional power that had convinced itself spirit could overcome steel.

Bradley wrote one final number on the board.

Total war production capacity ratio, United States to Japan, 10 to1.

He set down the chalk and turned to face the room.

These numbers were public, published in newspapers, industry, journals, government reports.

Any nation with intelligence services could have known them.

Most did know them.

Your government certainly knew them.

Silence in the room, heavy, suffocating.

Then Ko stood up.

Her legs were shaking, but she forced herself to stay upright.

She spoke in broken English, her voice cracking with emotion.

“You knew.

You knew these numbers and still sent us.” Bradley looked at her, his expression didn’t change.

“Ma’am, we didn’t send you.

Your government did.” “But you published.

You told everyone how strong you were.” “Yes, ma’am, we did.” “Then why?” Her voice broke completely.

“Why did they send us if they knew?” The translator was crying now, barely able to get the words out.

Other women in the room were standing.

Some were shaking.

Others had their hands over their mouths.

Bradley’s face softened slightly.

Just slightly.

I can’t answer that, ma’am.

That’s a question for Tokyo, not Washington.

Rachel stood in the back row, her mind working through the implications.

Every soldier she treated after 1942.

Every boy who died believing that his sacrifice meant something.

She’d been at Saipan when it fell.

Had watched men throw themselves off cliffs rather than surrender.

Had seen families jump into the sea with their children because they believed capture was worse than death.

If the war had been unwinable since 1942, then every death after that point had been unnecessary.

Not sacrifice, not honor, just waste.

Deliberate calculated waste of human life by leaders who knew the truth and chose to keep fighting anyway.

The math was simple and brutal.

Millions dead for nothing, for pride, for the egos of men in Tokyo who couldn’t admit they’d made a mistake.

Rachel felt something hot and jagged lodge itself in her throat.

Not grief anymore.

Rage.

Pure incandescent rage at the people who’d done this, who’d lied and sent people to D and called it patriotic duty.

Around her, the room was dissolving into chaos.

Women were crying, shouting, demanding answers that Bradley couldn’t give them.

The translator had given up trying to keep up with the flood of Japanese.

Guards moved toward the doors, uncertain whether they needed to intervene.

Harrison stepped forward and raised his hand.

The room quieted slightly.

Major Bradley has given you facts,” Harrison said through the translator.

“What you do with those facts is up to you, but I’ll tell you this.

Your leaders gambled your lives on a war they knew they’d lost.

That’s not honor.

That’s cruelty.

And you deserve better.” He gestured to the guards.

Dismissed.

Take the rest of the day.

Think about what you’ve heard.

The women filed out in silence.

The rage was building, but it had nowhere to go.

Not yet.

September became October.

October became November.

The Wisconsin autumn settled in with cold rain and early darkness.

The women adapted.

They learned more English.

They spent hours in the library reading everything they could get their hands on.

They [snorts] asked questions of the guards, the nurses, anyone who would talk to them.

Rachel buried herself in medical texts, modern nursing techniques, surgical procedures, pharmarmacology.

She took notes in cramped handwriting, filling notebook after notebook with information.

When she went home, whenever that happened, she would take this knowledge with her, would use it to save lives, would make sure that some good came out of this nightmare.

She worked alongside Sergeant Coleman in the infirmary.

sometimes observing, learning.

Coleman taught her about antibiotics, about sterilization, about all the things that made modern medicine work.

They didn’t talk much, didn’t need to.

The knowledge passed between them in demonstrations and careful instruction.

Enemy and ally working together to preserve life.

There was something profound in that.

Hannah found books about American engineering, bridge design, structural mechanics, earthquake resistant buildings.

She devoured them.

her young mind soaking up concepts she’d never encountered in her truncated university education.

She sketched designs in the margins of her notebooks, dreamed about buildings that could withstand disasters, about infrastructure that serve people instead of empires.

One afternoon, she showed her sketches to a young private who was guarding the library.

He looked at them with genuine interest and asked her questions about loadbearing calculations.

They spent an hour talking about physics and design.

The conversation halting and awkward because of the language barrier, but real nonetheless.

When the private shift ended, he shook her hand like a colleague, like an equal.

Hannah went back to her barracks that night and cried.

Not from sadness, from the realization that she’d spent more time talking about engineering with an enemy soldier than she’d ever been allowed to in her own country.

Ko became a fixture in the library reading newspapers cover to cover comparing what she read now to what she’d broadcast during the war.

Every article was a rebuke.

Every mundane story about American life was proof that the scripts she’d read had been fabrications.

She started writing her own scripts, not broadcasts, confessions maybe, or testimony.

She wrote about what she’d seen, what she’d learned, what she now understood about the lies she’d helped spread.

She didn’t know what she’d do with these writings, but she knew someone needed to document this.

Someone needed to tell the truth, even if it was painful, especially if it was painful.

Martinez found her in the library one afternoon, hunched over a newspaper, muttering to herself in Japanese while she wrote notes.

He approached carefully, “Ma’am, you doing okay?” Ko looked up, startled.

Her English had improved in the past 2 months.

I read, I write, I try to understand.

Understand what? Why? Why they lied? Why they sent us? She gestured at the newspaper.

America is strong.

We knew.

We had to know.

But they told us you were weak.

Dying.

Why lie? Yeah.

Martinez pulled out a chair and sat down across from her.

He thought about his daddy’s words about mercy and strength.

About what it meant to be American.

Maybe because if they told the truth, people wouldn’t have fought, he said carefully.

Maybe the only way to make people die for a lost cause is to lie to them about it being lost.

Ko stared at him, then nodded slowly.

Yes, that is it.

That is exactly it.

She wrote that down in her notebook.

Martinez watched her write and felt something shift in his chest.

This woman wasn’t the enemy.

She was a victim trying to understand what had been done to her.

“What will you do?” he asked.

When you go home, tell truth,” Ko said simply.

“Someone must.

Might as well be me.” November 22nd, Thanksgiving.

Harrison made the announcement the night before.

Tomorrow is an American holiday called Thanksgiving.

It’s a day when we give thanks for what we have, for harvest and abundance and blessings.

You’ll see what it means to us.

The women were confused.

A holiday in a prison camp.

But Harrison was serious.

Martinez and the kitchen staff had been preparing for days.

The messaul was decorated with autumn leaves and paper turkeys made by American soldiers who’d gotten bored and creative.

Long tables were set with actual tablecloths, white tablecloths.

Like this was a restaurant and not a military facility.

The women filed in at and found places at tables that seated 20.

But this time there were American soldiers sitting with them.

Two or three per table mixed in with the prisoners.

Guards off duty, kitchen staff, medical personnel, all volunteers who’ chosen to spend their holiday eating with enemy prisoners.

Then the food arrived.

Turkeys.

Whole turkeys roasted golden brown so large that one bird could feed an entire table.

[snorts] Martinez and two other servers carried them in on platters, steam arising from the meat, the smell filling the room with something that transcended language or nationality.

It was the smell of abundance, of celebration, of life.

Mashed potatoes in bowls the size of buckets, gravy and boats, stuffing made with bread and herbs and sausage, cranberry sauce, deep red and glistening, green beans, corn rolls, butter and pies, pumpkin pies and apple pies, one for every two tables.

The crust golden and flaky.

The women stared at the spread like it was a hallucination.

Harrison stood at the front of the room and addressed them through the translator.

Thanksgiving is when Americans give thanks for abundance, for harvest, for blessings.

Today we give thanks that the war is over, that the killing has stopped, that we can break bread together as human beings, not as enemies.

He paused, looking around the room at 300 women and 50 American soldiers.

You are prisoners, yes, but you are also guests at our table.

This is American tradition to share what we have to show hospitality even to those who fought against us.

Eat.

Be welcome.

Martinez sat at Rachel’s table.

He’d volunteered for this shift, wanting to see how the women would react to a real American Thanksgiving.

He picked up a carving knife and began cutting slices from the turkey, serving each woman personally.

“Ma’am, white meat or dark meat?” he asked Rachel.

She stared at him, not understanding.

He pointed to different parts of the turkey.

“White, dark, which you want, white,” she said softly.

He carved a thick slice and placed it on her plate.

Then added another, then spooned stuffing beside it, gravy over everything cranberry sauce on the side.

He did the same for each woman at the table, treating them like honored guests at a family dinner.

Rachel looked down at her plate, at least a pound of food, misho, more than she’d eaten in a single meal in years.

And this was normal for them.

This was tradition.

They did this every year.

She picked up her fork and cut a piece of turkey.

The meat was tender, falling apart at the touch.

She put it in her mouth and tasted salt and herbs and the kind of rich flavor that only came from meat that had been raised with enough food and cooked with care.

Her eyes filled with tears.

Around the table, other women were having the same reaction.

The food was too good, too abundant, too casual.

It was proof of everything they’d learned condensed into one meal.

America wasn’t just strong, it was so strong, it could afford to be generous.

So wealthy it could waste food and not notice.

So secure it could feed its enemies like family.

At the table behind Rachel’s, Hannah was laughing.

Actually laughing at something a young private had said.

The private was teaching her how to say Thanksgiving in English, exaggerating the pronunciation to make her laugh more.

They were passing a basket of rolls back and forth, taking turns buttering them, acting like this was completely normal.

Like sharing bread with the enemy was just what people did.

Ko sat next to Martinez and watched him eat.

He ate quickly, efficiently like someone who’d grown up around food and took it for granted.

He reached for seconds without hesitation.

Piled his plate high again, and the servers didn’t blink.

Just brought more food from the kitchen.

More turkey, more potatoes, more everything.

In Texas, Martinez said between bites, Thanksgiving is even bigger than this.

My mama makes three turkeys.

Three plus ham plus all the sides.

We got cousins coming from all over.

Food everywhere.

More than we can eat.

Ko absorbed this.

You have Thanksgiving every year.

Yes, ma’am.

Every November.

Been doing it since before I was born.

and always this much food.

Yes, ma’am.

That’s the point.

Show gratitude for what you got by sharing it.

Ko thought about the newspaper articles she’d read, about surplus grain shipments to Europe, about warehouse storage problems, about factory workers striking for higher wages because they could afford to be picky about their jobs.

All of it connected.

All of it proof of a nation so rich that generosity was easy.

Waste was acceptable.

Abundance was normal.

She looked around the messaul at 300 women eating until they were full for the first time in years.

At American soldiers laughing and joking and treating prisoners like people.

At the piles of food that kept coming from the kitchen.

This wasn’t an act.

This wasn’t propaganda.

This was who they were.

And her government had lied about all of it.

The meal lasted 2 hours.

When it was over, every woman had eaten more than she thought possible.

Plates were scraped clean.

Pie was devoured.

Coffee cups were refilled multiple times.

As the women filed out of the mess, Rachel found herself walking beside Harrison.

She’d been practicing a phrase in English for days, waiting for the right moment.

“Captain Harrison,” she said carefully.

“Thank you for this, for everything.” Harrison looked at her.

really looked at her, saw not an enemy, but a young woman who’d been lied to and starved and sent to die for a cause that was already lost.

A woman who was learning the truth and didn’t quite know what to do with it yet.

You’re welcome, he said.

But understand something.

This isn’t charity.

This isn’t us being nice to prisoners.

This is just how we do things.

This is what being American means.

We have the power to be cruel.

We choose mercy instead.

remember that when you go home.

Rachel nodded.

She would remember.

She would remember all of it.

December brought snow and photographs.

Official photographs from Japan.

Documentation of the atomic bombs.

Images that would define the war’s end and haunt everyone who saw them.

Hiroshima, Nagasaki.

Cities flatten.

Buildings reduced to rubble.

Shadows burned into walls where people had been standing when the flash came.

The devastation was total, absolute.

Nothing remained but ash and twisted metal and the ghosts of what had been.

Rachel stared at the photograph of Hiroshima for a long time.

She’d grown up in that city, knew its streets.

The hospital where she trained was visible in a pre-war photograph shown for comparison.

In the after photograph, it was gone.

Just rubble.

Everything was rubble.

Her family had lived 3 miles from the epicenter, the right distance to survive the initial blast, but close enough that radiation would have been severe.

She didn’t know if they were alive, didn’t know if her brother had survived.

Didn’t know if the house was still standing or if her parents had been reduced to shadows on a wall.

The grief was physical, a crushing weight on her chest that made breathing difficult.

But underneath the grief was something harder, colder, more focused.

Her government had known had known since 1942 that the war was unwininnable.

Had known the Americans had weapons Japan couldn’t match.

Had known that continuing to fight would lead to more deaths, more destruction, more suffering.

And they’d fought anyway.

Sent boys to die on ethlands that didn’t matter.

Sent civilians to burn in firebombing raids.

Kept fighting until America had to drop atomic bombs just to force a surrender.

Every death after 1942 could have been prevented.

Everyone.

If Tokyo had just admitted the truth and surrendered, but they’d been too proud, too convinced that dying was better than losing face.

Rachel looked at the photograph of her destroyed city and felt rage replace grief.

That night, the women gathered in the largest barracks.

Not for any official reason, not because they’d been ordered to.

They just came one by one until all 300 were crowded into a space meant for 60.

Nobody had organized this.

Nobody had planned it, but it happened anyway because the anger needed somewhere to go.

Hannah spoke first.

She was the youngest, but her voice carried.

They knew.

The generals, the ministers, the emperor’s advisers, they all knew, heads nodded in the dark.

The numbers were public.

America published everything.

Our leaders could read English.

They knew we couldn’t win.

They knew it.

In E42, maybe earlier.

And they sent us anyway.

Why? Silence, heavy, suffocating.

Then Ko stood.

Her voice shook with fury.

I’ll tell you why.

Because admitting defeat meant admitting they were wrong.

And they’d rather kill us all than admit that.

The room erupted.

Not in agreement, in rage.

pure crystalline rage that had been building for weeks and finally found its voice.

“Every script I read about American starvation was a lie,” Ko continued nearly shouting.

“Now, every broadcast about imminent victory was a lie.

Every boy who died believing his death meant something died for a lie.

” “I held dying soldiers,” Rachel said, standing into the back.

Her voice was quiet, but it cut through the chaos.

I whispered that their sacrifice was sacred.

I lied to them as they died, but I didn’t know I was lying.

I believed it, too.

Her voice cracked.

Our government knew.

They sent those boys knowing it was for nothing.

That’s not war.

That’s murder.

The word hung in the air.

Murder.

300 voices rose in agreement.

Not harmony.

Discord.

Raw, unfiltered rage at the people who’ done this to them.

They knew.

Pa, they killed us four.

Every death was murder.

The barracks shook with fury.

Guards outside heard but didn’t intervene.

Harrison had given orders.

Let them rage.

They’d earned it.

The rage lasted an hour, maybe more.

Women shouting in Japanese, crying, demanding answers that couldn’t be given.

Demanding justice that might never come.

Then Harrison appeared in the doorway.

The room fell silent.

Every woman turned to look at him, expecting punishment for the outburst, expecting to be told to quiet down and accept their place as prisoners.

Instead, Harrison said two words.

“You’re right.” Shock rippled through the room.

“You’re right,” he repeated, stepping inside.

“Your leaders knew they gambled your lives on a war they knew they’d lost.” “That’s not honor.

That’s cruelty.

And you deserve better.” He paused, looking around at 300 women who’d been broken by lies and were now being rebuilt by truth.

But you survived.

You’re here.

And when you go home, you’ll carry the truth with you.

You’ll rebuild your country on truth, not lies.

That’s how you honor the dead by making sure the lies die, too.

His words didn’t erase the anger, but they redirected it, gave it purpose, gave it meaning.

The women would go home eventually.

And when they did, they would tell the truth.

All of it.

No matter who tried to stop them.

That became their mission, their reason for surviving.

Truth as resistance, truth as revenge.

Winter settled over Camp McCoy.

Snow covered the grounds.

The women learned to navigate Wisconsin.

Cold bundled in coats provided by the Red Cross.

They threw themselves into learning.

English classes every day.

Library time extended to 6 hours.

vocational training and typing mechanics, teaching methods.

Coleman ran nursing refresher courses, modern techniques, American standards.

Rachel attended every session, taking notes, asking questions, absorbing everything.

She was building a foundation for what came next, for the clinic she would open in Hiroshima, for the lives she would save.

Martinez taught basic agricultural methods adapted from his Texas farm experience.

Emma attended those sessions, learning about crop rotation and soil management and mechanized farming.

Knowledge she would take back to her village.

Hannah studied engineering texts late into the night sketching building designs that could withstand earthquakes.

Dreaming of a rebuilt Japan that was stronger, safer, better.

Ko wrote pages and pages of testimony about what she’d seen, what she’d learned, what she now understood about the lies she’d helped spread.

She would become a teacher.

she decided would spend the rest of her life teaching truth to make up for the years she’d spent broadcasting lies.

The guards and prisoners stopped being enemies and became something else.

Not quite friends, but not hostile.

Human beings sharing space and finding common ground in unexpected places.

Martinez and Hannah exchanged letters after she taught him basic Japanese phrases.

He told her about his family’s ranch in Texas.

She told him about her plans for earthquake resistant buildings.

When spring came and departure orders were issued, Martinez gave Hannah a packet of Texas Blue Bonnet seeds.

“Plant these,” he said.

“Remember that enemies can become friends.” Hannah cried and hugged him.

“A prisoner hugging a guard.

Two people from opposite sides of a war finding humanity in each other.

” Coleman gave Rachel a thick medical textbook.

American nursing procedures.

“Teach others,” Coleman said.

save the lives we couldn’t save during the war.

Rachel took the book like it was sacred.

Because it was.

This knowledge had power.

The power to heal.

The power to prove that something good could come from something terrible.

Harrison gathered all 300 women for a final assembly on April 15th, 1946.

Ships were waiting in San Francisco.

It was time to go home.

“You came here as prisoners,” Harrison said.

You leave as something I don’t quite have a word for.

Not friends exactly, but not enemies either.

He looked at faces he’d come to know over 8 months.

Rachel, Hannah, Ko, Emma.

Women who’d arrived as skeletons and were leaving as people stronger, healthier, armed with truth.

You’ve seen America, the good and the beat, the waste and the abundance, the strength and the kindness.

Go home, rebuild.

And when you tell people about America, tell them the truth.

All of it.

The women boarded buses the next morning.

The same buses that had brought them eight months earlier.

But they were different now.

Walk differently, held themselves differently, carried themselves like people who’d survived something, and [clears throat] come out stronger.

April 20th, 1946, San Francisco Harbor.

300 women stood at the ship’s railing watching the skyline recede.

The same skyline they’d seen eight months ago when they could arrive broken and starving and convinced they were going to die.

Now they watched it disappear and felt something complicated.

Not gratitude exactly, but understanding, respect maybe.

Recognition that the enemy they’d been taught to hate was more complex than propaganda had allowed.

Rachel stood beside Emma Ko and Hannah.

The four of them had become close over the months, bonded by shared experience and shared rage and shared purpose.

Emma opened her journal and read aloud the final entry.

They never hid their strength.

We hid our weakness.

That was our real defeat.

Ko added, “But now we know the truth, and truth is the only foundation worth building on.

” Rachel looked at the city disappearing into fog.

We go home to ruins, but ruins can be rebuilt.

on truth this time.

Hannah clutched her packet of blue bonnet seeds.

The emperor called it sacred war.

It was just war.

Brutal, stupid, wasteful.

We won’t make that mistake again.

The four women clasped hands and made a vow.

Tell the truth always, no matter what.

Rebuild Japan on honesty instead of mythology.

Honor the dead by refusing to let lies continue.

The ship pulled away from American shores carrying 300 women who would spend the rest of their lives proving that mercy is stronger than victory.

That truth is more powerful than propaganda.

That the real victory wasn’t military defeat.

It was transformation.

5 years later, Rachel ran a clinic and rebuilt Hiroshima.

20 nurses trained in American techniques.

Her brother, now 14, and healthy, studied medicine.

They saved hundreds of lives using knowledge learned from enemies who chosen kindness.

20 years later, Hannah’s engineering firm had designed 30 earthquake resistant buildings across Tokyo.

The skyline included her work.

She kept Texas blue bonnets on her desk, blooming every spring.

A reminder that bridges could be built across any divide.