August 18th, 1945.

Morning mist hung over an American prison camp in Manila.

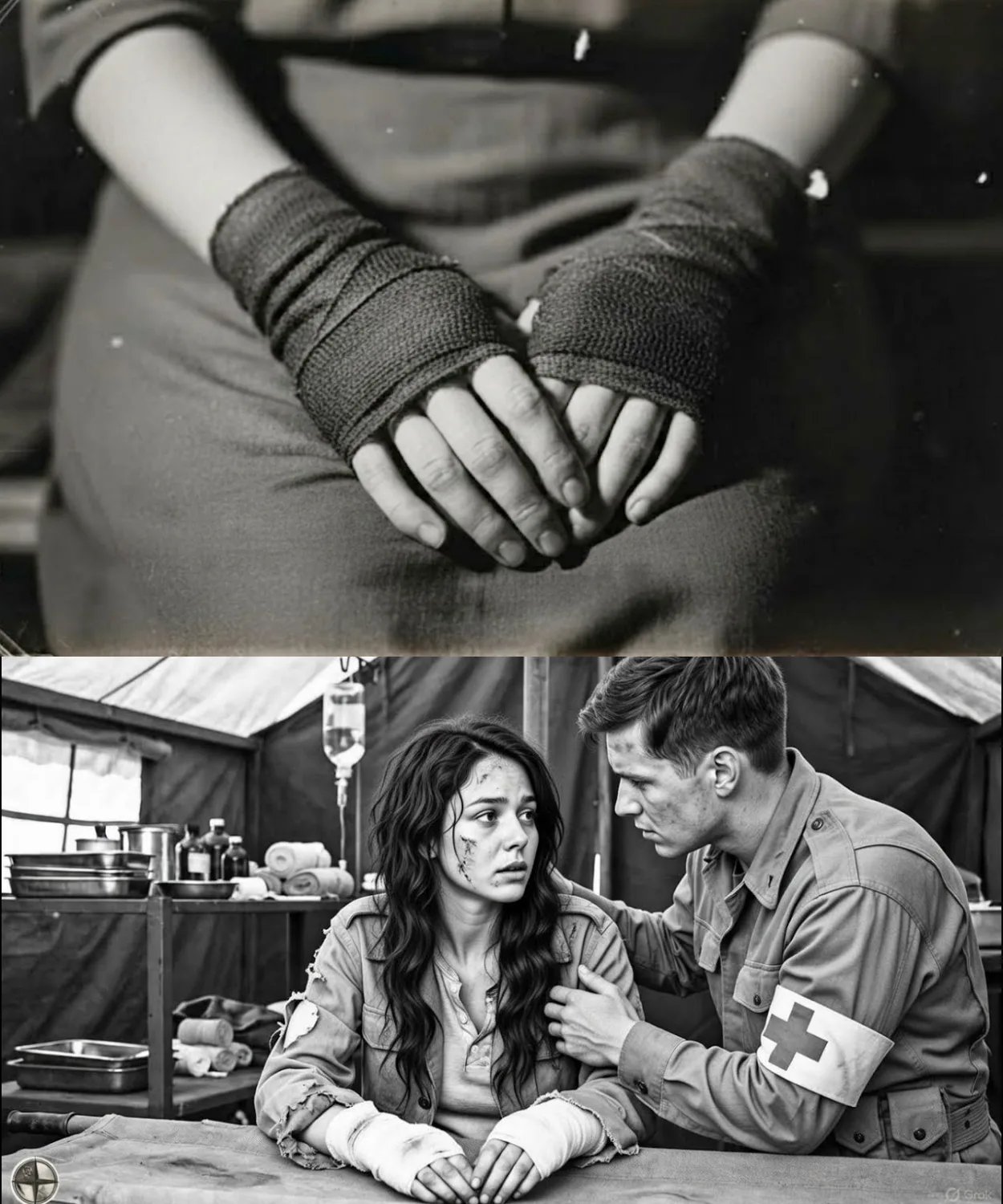

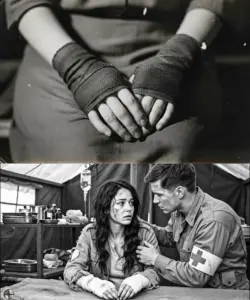

Inside a canvas tent, a young Japanese nurse sat quietly, a fresh bandage on her arm.

She had been told capture meant shame, hunger, even death.

But instead, an American medic handed her a steaming bowl of stew.

The smell of coffee filled the air.

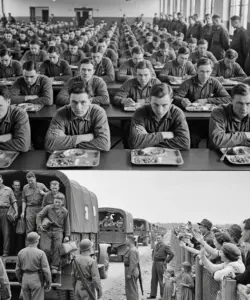

The sound of metal trays echoed across the yard.

These women had sworn to die before surrender.

Now they were given food, books, and even letters home.

The greatest shock, the enemy cared for them while their own country was starving.

This was no lie, no trick.

It was real life and it changed everything they believed.

Stay with us for this untold story.

Don’t forget to subscribe, like this video, and watch till the end to support our work and uncover the full truth.

August 18th, 1945.

The humid air clung to the earth outside Manila as a column of weary women stepped through the gates of an Americanrun P compound.

Their uniforms were torn, their bodies gaunt from weeks of hiding, and their minds braced for humiliation.

Each had been raised under the iron weight of Bushido.

The warriors code that drilled into them that surrender was not only shameful, but worse than death.

Japanese training manuals warned that Allied troops would rape, starve, or murder captives.

Mothers whispered the same into the ears of their daughters.

In those first heavy minutes, the silence of the camp pressed on them like an omen.

Instead of boots striking their backs, they heard the sharp clang of mess tins and the metallic rattle of ladles against steel pots.

The smell of boiled beef and onions drifted across the yard.

One woman, a nurse barely 20, later wrote in her diary, “I thought I was hallucinating.

I had prepared for a bullet, and instead they gave me bread.” The paradox was cruy vivid.

At that very hour, her homeland staggered beneath ash and famine.

Allied firebombing had left Tokyo and Osaka in smoldering ruins.

In rural prefectures, families survived on millet and roots.

Reports from Japan in late 1944 suggested civilians consumed fewer than 2,000 calories per week, less than many American prisoners received in a single day.

Yet here, in enemy hands, tables lined with food appeared like something from another world.

Military numbers add weight to this strangeness.

By the wars end, somewhere between 35,000 and 50,000 Japanese soldiers and a smaller but significant number of women were held in American captivity.

They were not supposed to exist at all.

Surrender had been drilled as unthinkable.

To Japanese eyes, the very fact of their survival was scandal enough that survival was gilded with blankets, cigarettes, and medical care seemed like fantasy bordering on betrayal.

Eyewitnesses confirm the bewilderment.

An American medic stationed in the Philippines recalled, “They looked at me like I was an apparition.

One girl kept asking if the food was poisoned.

When I tasted it in front of her, she finally ate and then she wept.

The first morning routine burned into memory, the scrape of spoons on metal, the weight of cotton sheets over exhausted limbs, the faint comfort of disinfectant in the infirmary.

For women conditioned to expect degradation, these sensory details carried more power than speeches.

The paradox became undeniable.

Captivity was not punishment, but reprieve.

This wasn’t propaganda.

It was reality, and reality itself began to corrode the stories they had carried since girlhood.

The training of years met the facts of a single day, and the contradiction was impossible to ignore.

But the shock of first impressions was only the beginning.

what they saw next.

The quiet, almost casual acts of kindness would cut even deeper into the myths they had believed.

The second day of captivity began not with orders barked in a foreign tongue, but with the clatter of a metal pale and the hiss of coffee poured into tin mugs.

A nurse sat in the corner of the mess tent, watching a US private press a steaming cup into her trembling hands.

She had been told that Americans were savages, men who would laugh as they tormented prisoners.

Instead, this soldier gave her something warm to drink and looked away as if granting her privacy.

That small mercy pierced more deeply than violence ever could.

Moments like these became the quiet turning points.

A sergeant paused during roll call to light a cigarette for a prisoner.

A medic bent to lace the boot of a woman with bandaged hands.

One of the Japanese recalled years later, “They tied the bandage so gently, I wanted to cry.

I thought of my own brother lost in Burma, and wondered if someone had shown him the same.

The gestures seemed almost careless in their simplicity, yet they chipped at the walls of propaganda with every repetition.” Here was the irony.

Acts so ordinary to Americans carried the weight of revelation to those who had been trained to see only cruelty.

Statistics underscore the scale of this paradox.

By late 1945, US camps across the Pacific were housing tens of thousands of Japanese PS.

Every one of them received rations in line with the Geneva Convention, three meals a day, averaging 3,500 calories, nearly double what the average Japanese civilian consumed back home.

The very enemy they had been told would starve them, now fed them better than their own nation could.

And yet trust was not immediate.

Some prisoners hesitated, suspecting poison in the stew or hidden malice behind the blankets, the clang of the serving ladle, the steam rising from a bowl of beans.

Even the faint sweetness of cornbread, all of it felt like a trap too kind to be real.

Only after repeated offerings, untouched food left untainted, did the doubts begin to loosen their grip.

The sounds of the camp carried their own meaning.

The scrape of boots on gravel, the low laughter of guards playing cards, the distant notes of a harmonica drifting at dusk.

For women who expected jeers and blows, these ordinary sounds of life suggested something stranger.

Normaly.

One American officer summarized the policy bluntly in his report.

We keep them alive because it helps us win the war faster.

A fed prisoner works, talks, and does not fight again.

That is victory by another means.

For the captives, however, this strategy felt indistinguishable from compassion.

The motivation mattered little.

The experience was what seared itself into memory.

Every cigarette, every clean bandage, every untouched plate of food was another crack in the armor of ideology.

What had begun as survival was becoming a slow education, one small kindness at a time.

But daily mercies alone could not explain what unfolded next.

Beyond food and shelter, these women encountered something they had never imagined inside barbed wire.

The ordinary rhythms of comfort, learning, and even leisure.

By the third week of captivity, the shock of survival had settled into routine.

What began as disbelief became habit, rising at dawn, lining up for roll call, and then filing into the mess hall where steam curled from vats of oatmeal and coffee.

The prisoners were given spoons, not scraps, metal trays, not bare hands.

To those who had expected punishment, the sheer normaly of meals felt like a quiet miracle.

A woman who had served as a nurse at Batan later wrote, “The bread was soft.

I had not touched soft bread since before the war.

My fingers pressed it and I thought I was dreaming.” Her words capture how mundane comforts carried disproportionate power.

A slice of bread or the weight of a wool blanket became proof that everything she had been taught about the enemy was not only false but inverted.

The camp itself was an unassuming grid of wooden barracks, wire fences, and gravel paths.

Yet inside its boundaries, a strange paradox unfolded.

Prisoners lived with more stability than civilians in Japan’s bomb-shhattered cities.

Straw mats on the floor replaced cold earth.

Cotton sheets replaced rags.

Buckets of disinfectant.

Acrid and sharp replaced the wreak of infection.

Even the sounds were different.

No air raid sirens.

No wine of engines overhead, only the shuffle of guards and the clang of dinner bells.

Statistics reveal the scale of these mercies.

An official US Army report noted that Japanese PS were provided between 3,00 calories daily, beans, rice, bread, coffee, sometimes meat, or fruit.

Meanwhile, Allied estimates put the average Japanese civilian in 1944 at fewer than 2,000 calories a week.

The contrast was grotesque.

Soldiers and nurses who had come as enemies were fed more generously in captivity than their families in Tokyo or Kyoto could dream of at home.

Beyond food, the camps offered small projects.

Some prisoners were given vegetable seeds and allowed to plant gardens, the smell of tilled soil, reminding them of farms left behind.

Others swept, laundered, or worked in the infirmary.

These tasks were voluntary.

A way to pass the endless hours.

A few even asked for books, and American officers, almost amused, provided English primers and himnels.

Eyewitness accounts bring texture to this unlikely atmosphere.

One Japanese woman remembered hearing laughter through the thin barrack walls as fellow prisoners tried to pronounce English words, stumbling over apple and book.

Another recalled her astonishment when guards permitted them to listen to a photograph.

The scratch of jazz records, trumpets and drums echoed into the night.

Music utterly foreign yet strangely comforting.

This was the heart of the paradox.

Captivity expected to be a living death had become a fragile version of security.

We lived as if in a dream, one diary noted.

The enemy gave us medicine.

They allowed us to wash.

I had forgotten what it felt like to be clean.

Still, every act of mercy carried a shadow.

For each blanket pulled over their shoulders, they remembered a cousin or brother shivering in the ruins of Nagoya.

For every bowl of rice set before them, they imagined their mothers scraping ash for roots.

Kindness tasted of guilt as much as relief.

And yet the pattern of daily mercies continued, each day blurred into the next until life behind barbed wire resembled something too dangerous to name comfort.

But it was only when they saw the numbers in black and white, statistics of starvation, mortality, and survival, that the contrast between captivity and home turned unbearable.

Numbers have a way of stripping illusions bare.

For the women behind the wire, the shock of blankets and bread was visceral.

But the facts, when whispered through rumor or read in confiscated reports, struck even deeper.

By August 1945, the United States held between 35,000 and 50,000 Japanese prisoners across the Pacific and on the American mainland.

Their survival rates were staggering.

More than 95% lived to see repatriation.

In brutal contrast, Allied captives in Japanese camps faced a death rate approaching 1 in three.

Those numbers became a mirror no one could ignore.

One American intelligence officer summarized the comparison with chilling brevity.

Our camps produce workers.

Theirs produce corpses.

Prisoners who heard these figures wrestled with a cruel paradox.

To live under the enemy’s care meant outlasting their comrades who had remained loyal to the emperor.

Civilian conditions at home painted the contrast in even harsher tones.

Allied estimates reported that by 1944, the average Japanese civilian consumed fewer than 2,000 calories each week.

Mothers boiled tree bark to stretch rations.

Children fainted in schoolyards.

Yet in American camps, prisoners received three meals a day, totaling nearly that much in a single sitting.

The clang of a ladle filling soup bowls was in its own way an indictment of a starving empire.

Witness voices echo this torment.

A young P nurse later confessed, “When I ate, I felt I betrayed my family.

Each spoonful tasted of shame, but also of survival.” Another remembered reading a smuggled note about Osaka’s firebombing while cradling a cup of coffee.

The bitter steam blurred with her tears as she whispered, “How can this be real?” The sensory contrasts were unbearable.

In Tokyo, the smell of ash and sewage.

In captivity, the aroma of bacon drifting across camp at dawn.

In Nagoya, silence broken only by sirens and falling bombs.

In the compound, the lazy hum of a guard’s harmonica.

The women lived caught between two worlds.

Their homeland’s agony and the enemy’s abundance.

And still, the irony cut deeper.

These mercies were not born of compassion alone.

They were policy, deliberate, and calculated.

American commanders knew that feeding and protecting prisoners yielded cooperation, intelligence, and labor.

Humane treatment was both strategy and morality.

A weapon of abundance wielded with quiet precision.

This wasn’t propaganda.

It was reality.

Reality so stark that it began to corrode the very foundations of belief the captives had carried since girlhood.

If their teachers, parents, and officers had lied about the cruelty of the enemy, what else had been a lie? But information spread in subtler ways than rations and statistics.

In time, it was not only meals that reshaped the prisoner’s minds.

It was letters, language, and the fragile bridge of communication between enemy and captive.

It began with a sheet of paper, thin, lined, foreign, yet offered freely to women who expected nothing but silence.

Guards told them they could write home, and many stared in disbelief.

In Japan, surrender was dishonor, admitting survival as a prisoner could endanger a family.

Still, the temptation was overwhelming.

One young nurse pressed her pencil to the page and wrote, “I am alive.

I eat.

I sleep on a bed.

Do not worry.

Letters became bridges, though not all reached their destinations.

American sensors intercepted many, studying handwriting for hidden codes, and sometimes filing them away as intelligence.

Yet, even filtered words carried power.

They chipped at the Empire’s narrative of inevitable death in captivity.

Some reports later suggested that intercepted letters informed American psychological campaigns, proving that Japanese troops could in fact live well as prisoners.

Language itself became another frontier.

A few guards amused taught the women English words.

Apple, book, friend.

At first, the syllables tumbled awkwardly, met with laughter that softened into learning.

Some PS requested dictionaries and American officers supplied them.

Soon, fragments of conversation filled the compound, halting greetings, attempts at songs.

One woman remembered, “We practiced at night whispering strange words as if they were magic charms.” Statistics highlight how widespread this cultural exchange became by late 1945.

US military reports noted over 20 organized classes in P camps across the Pacific.

English instruction, typing, even agriculture.

For women, especially those trained as nurses or clerks, these lessons were lifelines.

They gave structure, purpose, and a sense of growth rather than decay.

The sensory layer of these encounters lingers in memory.

The scratch of pencil against paper.

The faint ink smell mixing with dust in the barracks.

The rhythm of chalk tapping on a board as a guard drew letters.

The awkward laughter of students repeating words in chorus.

A sound utterly at odds with barbed wire overhead.

And through these fragile connections, trust deepened.

Some prisoners began to volunteer information, not from betrayal, but from a need to speak to be understood.

One recalled, “I told them about our rations, about how weak we were before capture.

It slipped out like confession.

They listened, not with anger, but with curiosity.

The paradox sharpened again.

Communication once thought impossible between enemies, flourished in captivity.

Instead of silence and suspicion, there were letters, lessons, and conversations that bridged cultures.

What began as survival had become dialogue and dialogue began to reshape identity itself.

Yet every word carried a cost.

Behind each attempt at English, behind each letter home, loomed the shadow of shame.

Were they still loyal daughters of Japan? Or had they become something else, survivors who had tasted the forbidden kindness of an enemy? That question would haunt them more deeply as captivity wore on.

For while daily mercies offered comfort, they also ignited a battle within the heart, shame against gratitude, loyalty against life itself.

The longer captivity stretched, the heavier the weight of contradiction became for women raised on stories of samurai honor and imperial duty.

Every bowl of soup, every folded blanket was both salvation and betrayal.

At night, under the wine of insects and the faint creek of barrack timbers, some whispered of ending their lives.

If our families knew we lived like this, one nurse recalled, “Would they even want us back?” The paradox was unrelenting.

To survive was to break faith.

Yet to die would dishonor the kindness shown by those once called monsters.

Within that tension, identities splintered.

Some clung fiercely to the emperor’s image, bowing before photographs, murmuring prayers at dawn.

Others quietly admitted in diaries later recovered that their beliefs were unraveling.

Statistics sharpen the torment.

Allied analysts estimated that more than 30% of Japanese PS expressed suicidal thoughts within the first month of captivity, though actual attempts were far fewer.

The numbers suggest an inner battlefield as punishing as any fought with rifles.

The sensory markers of this struggle remain vivid.

The crackle of paper as a woman tore up a hidden note declaring her shame.

The muffled sobs in the dark after a harmonica drifted across camp, reminding them of a lullaby once sung at home.

Even the smell of soap, sharp, clean, almost medicinal, became a reminder that they were cared for by the very enemy they had been told to despise.

Voices from both sides reveal the depth of this dissonance.

A Japanese P nurse admitted decades later.

I wanted to hate them.

Each act of kindness cut me like a blade.

I felt my loyalty draining away.

An American guard observed the same paradox from another angle.

They looked guilty when they ate, like every spoonful was a crime.

And yet slowly the balance shifted.

Shame did not vanish, but survival began to claim its own legitimacy.

A woman who once hid her face while receiving medicine later confessed in her journal.

I chose to live, and living is also courage.

These private reckonings marked the first cracks in an ideology that had demanded death over surrender.

Still, the question lingered.

What would become of them once the gates opened? To live well in captivity was one thing, but to return to Japan to families who had been taught that PWs were traitors was another.

The women carried this fear like a hidden wound, knowing the day would come when the barbed wire no longer separated them from the ruins of home.

The internal war of shame and gratitude could not be resolved inside the camp.

It would follow them back across the sea into a homeland they no longer recognized.

The gates finally opened in late 1945.

Columns of prisoners, women among them, were marched to trucks that rumbled toward harbors, crowded with gray painted transport ships.

The clang of chains on the pier, the salt bite of sea air, the drone of engines.

Every sound marked the end of captivity and the start of an uncertain return.

For months they had lived with blankets, bread, and books.

Now they faced a homeland reduced to rubble.

Tokyo lay blackened.

Aika smoldered.

Nagoya flattened.

Across Japan, more than 60 cities had been firebombed.

Estimates suggested that nearly 9 million people were homeless and millions more were malnourished.

The women stepped off gang ways into a nation unrecognizable where even survival itself was rationed.

One nurse recalled her first sight of Yokohama.

I saw children with bellies swollen from hunger.

I had eaten three meals a day in the camp.

Shame clawed at me.

The paradox of captivity returned in sharper form.

They had been fed by their enemies while their own countrymen starved.

Statistics painted the cruelty in stark numbers.

By the war’s end, Japanese rice production had collapsed to less than 50% of pre-war levels.

Black markets swelled.

Caloric intake for civilians plunged to around 1,600 calories daily.

In comparison, US PWS in Japan often endured less than 1,200 calories.

The inverse reflection of Japanese prisoners who had thrived in Allied custody.

The symmetry was haunting.

Reception at home was ambivalent.

Some families wept with relief, clutching daughters they thought long dead.

Others turned cold, seeing in their return only dishonor.

Rumors circulated that repatriated prisoners had been tainted by enemy propaganda.

A woman wrote bitterly in her journal.

We were not greeted as survivors, but as ghosts.

The sensory dissonance of return lingered in their bodies.

The smell of burning charcoal in ruined streets replaced the clean soap of camp showers.

The rough texture of tattered kimonos replaced cotton sheets.

Silence weighed heavier than the clang of American mess tins.

They had crossed from one paradox to another, from the abundance of captivity to the poverty of freedom.

American policy too shadowed their homecoming.

Many of the skills and fragments of English learned in camp now set them apart.

A handful found work with occupation forces, translating or nursing.

Others concealed their experiences, fearing stigma.

Survival had made them outsiders in both worlds.

alien to Americans, suspect to their own people.

And yet, even in the ruins, the memories of unexpected mercy could not be erased.

For some, it was the taste of coffee.

For others, the sound of music drifting from a guard’s harmonica.

For many, it was simply the fact of being alive when so many were not.

But survival was not the final chapter.

The true reckoning came later when historians and nations asked what these paradoxes meant and what lessons the world would carry forward from camps that became against all expectation a strange kind of sanctuary.

History often moves like a tide, rushing forward in waves of violence, then ebbing back to reveal the human fragments left behind.

For the Japanese women who had once stepped into American prison camps, their memories became artifacts of contradiction.

They had entered expecting starvation and humiliation.

They departed recalling warmth, food, and dignity.

It was a paradox that unsettled them for the rest of their lives.

On a personal scale, the legacy was profound.

A former prisoner later confessed, “I could not hate Americans after what I lived through.

They treated us better than our own army treated its women.” That confession carried weight in a society that demanded silence.

The irony of captivity that the enemy had offered kindness when their own leaders had not became a secret some carried like contraband hidden in diaries or whispered only to grandchildren decades later.

The statistics of the war underscored the contrast.

Japan had mobilized nearly 2.

5 million women into military and auxiliary roles yet provided almost no provisions for those captured.

Meanwhile, the United States, with its industrial engine producing 50 billion pounds of food annually by 1945, could feed even its prisoners well.

The abundance was not accidental.

It was systemic.

One nation fought with scarcity, the other with surplus, and surplus proved the stronger weapon.

But beyond numbers, there was the enduring question of perception.

To the women, captivity had revealed a truth.

Their wartime propaganda never allowed that the United States was not simply an enemy, but a society built on resources, infrastructure, and a culture of relative humanity.

They had come as indoctrinated subjects of empire, convinced Americans would treat them like vermin.

They left with memories of milk, soap, and sometimes even smiles.

This paradox reverberated in the broader story of the war’s aftermath.

Japan rebuilt under American occupation, adopting institutions, industries, and democratic reforms.

In a strange way, the same paradox lived again.

The conqueror had become a teacher that defeated a student.

Those who had lived the paradox most intimately.

The female prisoners embodied this shift in miniature.

From the smell of bread baking in camp ovens to the acrid smoke of firebombed Tokyo, their lives bridged two worlds, one of destruction, one of provision, they carried the weight of both, reminding future generations that survival in war is not always defined by strength or weapons, but by unexpected acts of humanity.

In the end, their testimony distills into one enduring lesson.

They had come as conquerors.

They left as students.

They entered believing captivity would strip them of dignity.

They departed realizing it had paradoxically preserved it.

And so when history tallies the weapons of World War II, tanks, planes, atomic bombs, it must also count another quieter force, abundance itself.

For in the end, America’s greatest weapon was not its bombs, but its ability to feed even those who had once sworn to die before surrender.