September 5th, 1945.

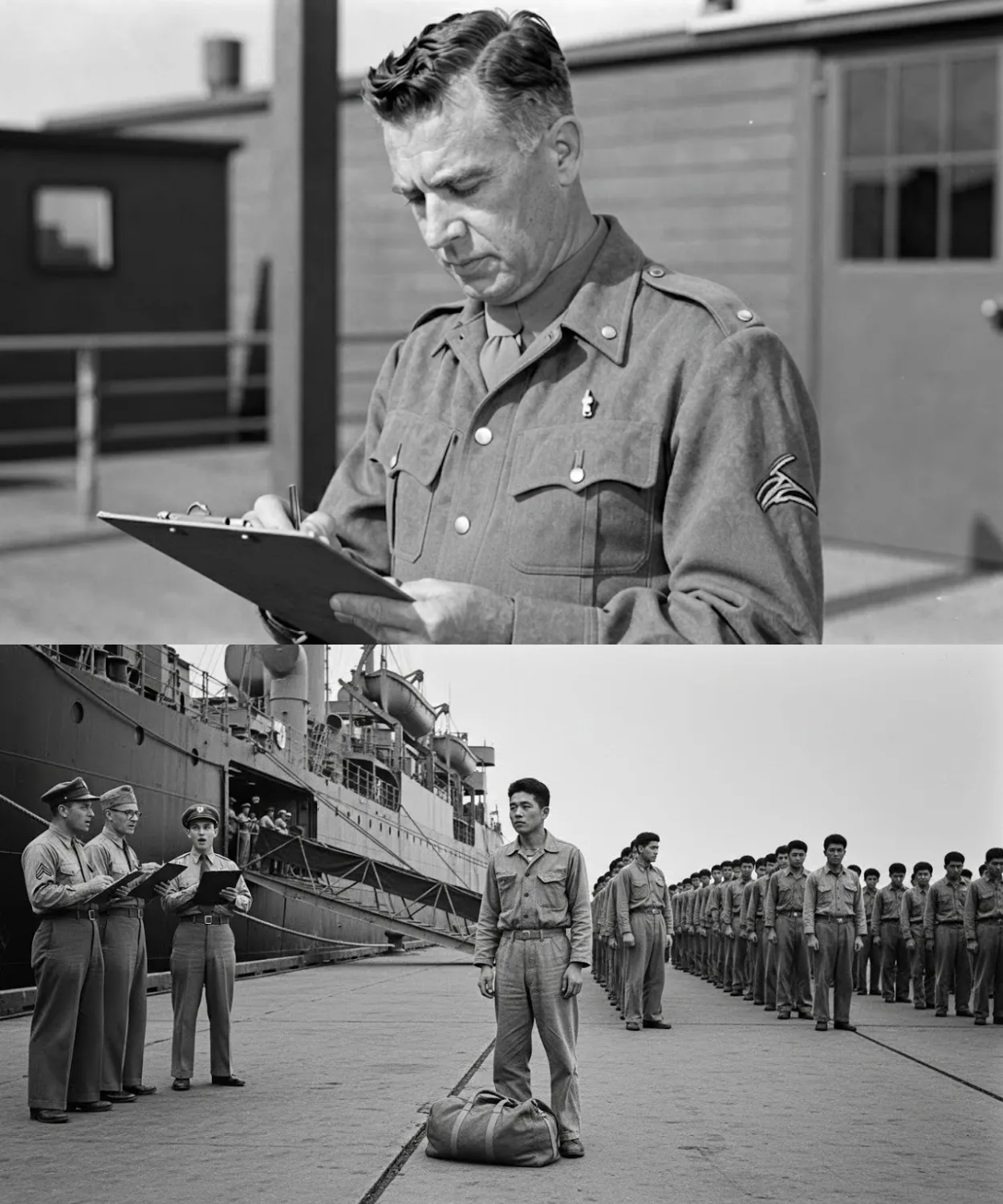

San Francisco Harbor sat beneath the slate gray sky as the transport ship SS Marine Phoenix bobbed at anchor, its hull freshly painted, its holds ready to carry 1,500 Japanese prisoners of war back across the Pacific.

On the deck, Captain Robert Morrison of the United States Army stood with his clipboard, checking names against his manifest.

The war had been over for 3 weeks.

The atomic devices had fallen on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in early August, and Emperor Hirohito had announced surrender on the 15th of that month.

Now came the administrative task of returning captured enemy soldiers to their homeland.

Morrison expected a smooth operation.

These men had been held at various camps throughout California for years.

Far from combat, well-fed according to Geneva Convention standards.

Surely they would be eager to see their families again.

He could not have been more wrong.

Before we dive into this story, make sure to subscribe to the channel and tell me in the comments where you’re watching from.

It really helps support the channel.

What Morrison and his superiors were about to witness would challenge every assumption about loyalty, propaganda, and the transformative power of unexpected kindness.

Over the next 72 hours, nearly 400 Japanese prisoners would refuse to board the ship home, triggering a crisis that revealed a truth the military had not anticipated.

Some men had been so profoundly changed by their captivity in America that they no longer recognized the country they had fought for.

The first sign of trouble came at 0800 hours that morning.

Sergeant Teeshi Yamamoto, formerly of the Imperial Japanese Army’s 16th Division, stood at the base of the gang plank with his duffel bag at his feet.

He was 32 years old, captured on Guadal Canal in late 1942 after his unit had been cut off and surrounded.

Behind him, a line of men in clean fatigues stretched back across the dock.

Morrison had organized them alphabetically by surname, expecting an efficient boarding process.

Yamamoto looked up at the ship, then down at his feet.

He did not move.

“Sergeant Yamamoto,” Morrison called through his interpreter, a Japanese American linguist named Henry Tanaka.

“Please proceed aboard.” Through Tanaka, Yamamoto replied, “I respectfully request permission to remain in the United States, sir.” Morrison blinked.

In 3 years of managing prisoner transfers, he had never heard such a request.

That’s not possible, Sergeant.

You’re a prisoner of war.

The war is over.

You’re going home.

With respect, Captain, I have no home to return to.

Yamamoto’s voice was steady, his eyes meeting Morrison’s directly.

My family lived in Hiroshima.

The words hung in the salt air.

Morrison felt something shift in his chest.

He had seen the photographs from Hiroshima, the ones that had circulated among officers.

The entire city had been reduced to ash and shadow.

The official estimate spoke of 70,000 deaths in the initial blast with thousands more dying daily from radiation sickness, though these numbers would not be fully known for months or years.

I understand, Morrison said quietly.

But the order stands.

We’ll help you locate any surviving family members once you’re processed in Japan.

Yamamoto shook his head slowly.

Are you misunderstand, Captain? Even if any of my family survived, I do not wish to return.

I have seen what America truly is.

I cannot go back to what I was told to believe.

Behind Yamamoto, murmurss rippled through the line of waiting prisoners.

Morrison saw heads nodding, saw men shifting their weight, saw the beginning of something he had no protocol for handling.

By noon, the situation had escalated beyond Morrison’s authority.

Rear Admiral Thomas Henderson arrived from the Prescidio, his face grave beneath his cap.

With him came Colonel James Whitfield, who had overseen the largest prisoner of war camp in California, located in the central valley near a town called Stockton.

Whitfield knew many of these men personally.

They convened in a warehouse office overlooking the dock, where Morrison had separated the refusing prisoners into a holding area.

Through the window they could see nearly 380 Japanese soldiers sitting in orderly rows, silent and patient.

Colonel, you’ve worked with these men for 2 years, Henderson said.

What the hell is going on? Whitfield pulled out a worn notebook, flipping through pages of observations he had made during his time at the camp.

Admiral, what we’re seeing is the result of something we didn’t plan for and didn’t expect.

We treated them according to the Geneva Conventions.

We fed them adequately, actually more than adequately.

We paid them for their labor when they volunteered for work details.

We allowed them male privileges, recreational activities, religious services.

We treated them like human beings.

Henderson frowned.

As we should have.

Yes, sir.

But they expected to be treated like animals.

They’d been told by their officers and their government that Americans were barbarians who would torture and execute prisoners.

Every single one of these men surrendered, believing they would be killed within days, if not hours.

Some had been told we would eat them.

Morrison, who had been listening quietly, spoke up.

I’ve interviewed dozens of them over the past 3 years, sir.

The propaganda they’d been fed was extraordinary.

They were told American soldiers wore necklaces made from Japanese ears and teeth.

That we would parade them through streets where civilians would stone them to death.

That our women were encouraged to mutilate prisoners for sport.

Henderson sat down heavily and instead instead we gave them three meals a day, medical care, clean barracks and baseball equipment.

Whitfield said we let them form education classes.

We provided them with reading material.

Many of them learned English from volunteer teachers who came from nearby towns.

They worked on farms during harvest season and were paid 80 cents a day in camp script they could use at the canteen.

They ate better than many American civilians during rationing.

The admiral was silent for a long moment, staring out at the seated prisoners.

Finally, he said, “Get me there, spokesman.

I want to understand this directly.” 20 minutes later, Sergeant Yamamoto stood before the three American officers with Henry Tanaka interpreting.

Yamamoto had been selected by the other prisoners to speak for them, not because he was the highest ranking.

There were several left tenants and even one captain among the refusers, but because he spoke the best English and had a reputation for thoughtfulness.

Sergeant Yamamoto, Henderson began, his voice formal but not unkind.

I want you to help me understand why you and these other men refuse to return to Japan.

The war is over.

Your emperor has ordered your forces to surrender.

Your duty is to return home.

Yamamoto stood at attention, his hands clasped behind his back.

When he spoke, his English was accented but clear, and Tanaka only occasionally needed to clarify a word.

Admiral Henderson, I will try to explain, though I fear my words are inadequate.

When I was captured on Guadal Canal, I believed my life was over, not because I thought I would die in combat, but because I had failed my emperor and my country by allowing myself to be taken alive.

I had been taught since childhood that death was preferable to capture.

Surrender was the ultimate disgrace.

He paused, gathering his thoughts.

In those first hours after the American Marines surrounded our position, I waited to be executed.

When I was instead given water and medical treatment for my wounds, I thought it was a trick, a cruel game before the real torture began.

But the torture never came.

Instead, I was transported to a camp in California, and there I experienced something I had no framework to understand.

Go on, Henderson said.

I was treated with dignity, Admiral.

Not because I had earned it or deserved it, but because you Americans seem to believe that all men deserved it simply by virtue of being human.

This was incomprehensible to me.

In the Imperial Army, dignity flowed from rank and obedience.

It was earned through service to the emperor.

It could be lost through failure or captured.

But here, even as a prisoner, even as an enemy, I was given respect.

Yamamoto’s voice grew stronger.

At the Stockton camp, I volunteered to work on tomato farms.

I was paid for my labor.

The farmers who employed us brought us cold water on hot days.

They showed us photographs of their sons who were fighting in Europe or in the Pacific.

They did not hate us, though they had every reason to.

One farmer, a man named Joseph Martinez, learned that I had studied agriculture before the conflict.

He spent hours teaching me about irrigation techniques used in California’s Central Valley.

He invited me to eat lunch with his family.

His wife made extra food so I could share it with other prisoners.

Their daughter, who was perhaps 8 years old, drew pictures for us with crayons.

Morrison saw tears forming in Yamamoto’s eyes, though the sergeant’s voice remained steady.

I began to understand that I had been lied to, Admiral, not just about how Americans would treat prisoners, but about what America was.

I had been told this was a weak nation, corrupted by individualism and materialism, lacking the spiritual strength of Japan.

But I saw ordinary Americans working harder than anyone I had known.

I saw them sacrifice for their families and their communities.

I saw them practice the very values of honor and duty that we Japanese claimed as uniquely our own.

But they did it without the cruelty and rigid hierarchy we had accepted as necessary.

Henderson leaned forward.

But surely you want to rebuild Japan.

Your country will need men like you.

Rebuild it into what, Admiral? Yamamoto’s question was sharp.

I have learned what my government did in China, in the Philippines, in Korea.

The other prisoners, we talk among ourselves.

We read the newspapers you provide.

We hear the accounts from guards who fought in the Pacific.

I know now about the occupations, the forced labor, the comfort women.

These are not the actions of a noble warrior culture.

These are the actions of a regime that valued conquest over humanity.

He took a breath.

When the devices fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I felt grief beyond measure.

Not for the defeat of Japan.

And I had already accepted that defeat was inevitable given American industrial might, but for all the innocent lives lost.

And then I felt anger because I realized those deaths were the final cost of lies my government had told.

They would never surrender because surrender meant admitting the entire foundation of their power was built on falsehood.

So they let two cities burn rather than face truth.

Colonel Whitfield spoke for the first time.

Yamamoto, even if everything you say is true, you’re still Japanese.

Where do you belong if not in Japan? Yamamoto met his eyes.

Colonel, you taught me something at the camp.

You made me read the American Declaration of Independence as part of the English education program.

It says, “All men are created equal and endowed with unalienable rights.” When I first read those words, I thought they were naive nonsense.

But I have lived under their application even as a prisoner and enemy.

I have seen what a society built on those principles can become.

It is not perfect.

I know about the segregation, the discrimination, the camps where Japanese Americans were held simply for their ancestry.

But the principles are sound, and I have watched Americans struggle to live up to them.

That struggle is honest.

That struggle is worthy.

He straightened.

I do not know where I belong, Colonel, but I know I cannot return to a place where I would have to pretend the last 3 years did not happen.

I cannot pretend I do not know what I know.

If I return to Japan and speak these truths, I will likely be killed as a traitor by the same militarists who led us to ruin.

If I remain silent, I will betray everything I have learned.

So, I ask to remain here, even as a prisoner, until some arrangement can be made.

I will accept any terms.

I will work any job.

I simply cannot board that ship.

The room was silent except for the distant sound of waves against the dock.

Admiral Henderson stood and walked to the window.

Outside the nearly 400 prisoners sat in perfect formation, waiting.

After a long moment, he turned back to Yamamoto.

What you’re asking is impossible under current military law, Sergeant, but I’m going to make some calls to Washington.

In the meantime, you and the others will remain here under guard.

I want you to select a committee of 10 men who can articulate their positions clearly.

We’re going to document everything you’ve told me, and we’re going to find out if there’s any legal pathway for what you’re requesting.

Yamamoto bowed deeply.

Thank you, Admiral.

That is all we ask, to be heard.

Over the next 2 weeks, as the SS Marine Phoenix sailed without its full complement of prisoners, a series of investigations began.

Military intelligence officers interviewed the refusing prisoners extensively.

What they discovered shook assumptions throughout the command structure.

Lieutenant Hiroshi Nakamura, captured on Saipan in mid 1944, had been a chemistry teacher before the conflict.

At the prisoner of war camp, he had been assigned to work in the camp’s sanitation detail, ensuring clean water and proper waste disposal.

He told his interviewers about the moment he realized American prisoners were receiving the same medical care as American soldiers in the camp hospital.

I was shocked, he said through an interpreter.

In the Imperial Army, we were taught that the weak deserved to perish, but here a soldier with dissentry was treated with the same urgency as an officer with a broken bone.

Every life was valued equally.

This was a revelation to me.

Private First Class Kenji Sato, 19 years old when captured on Ewima in February of that same year, had spent only 6 months in captivity, but those 6 months had been enough.

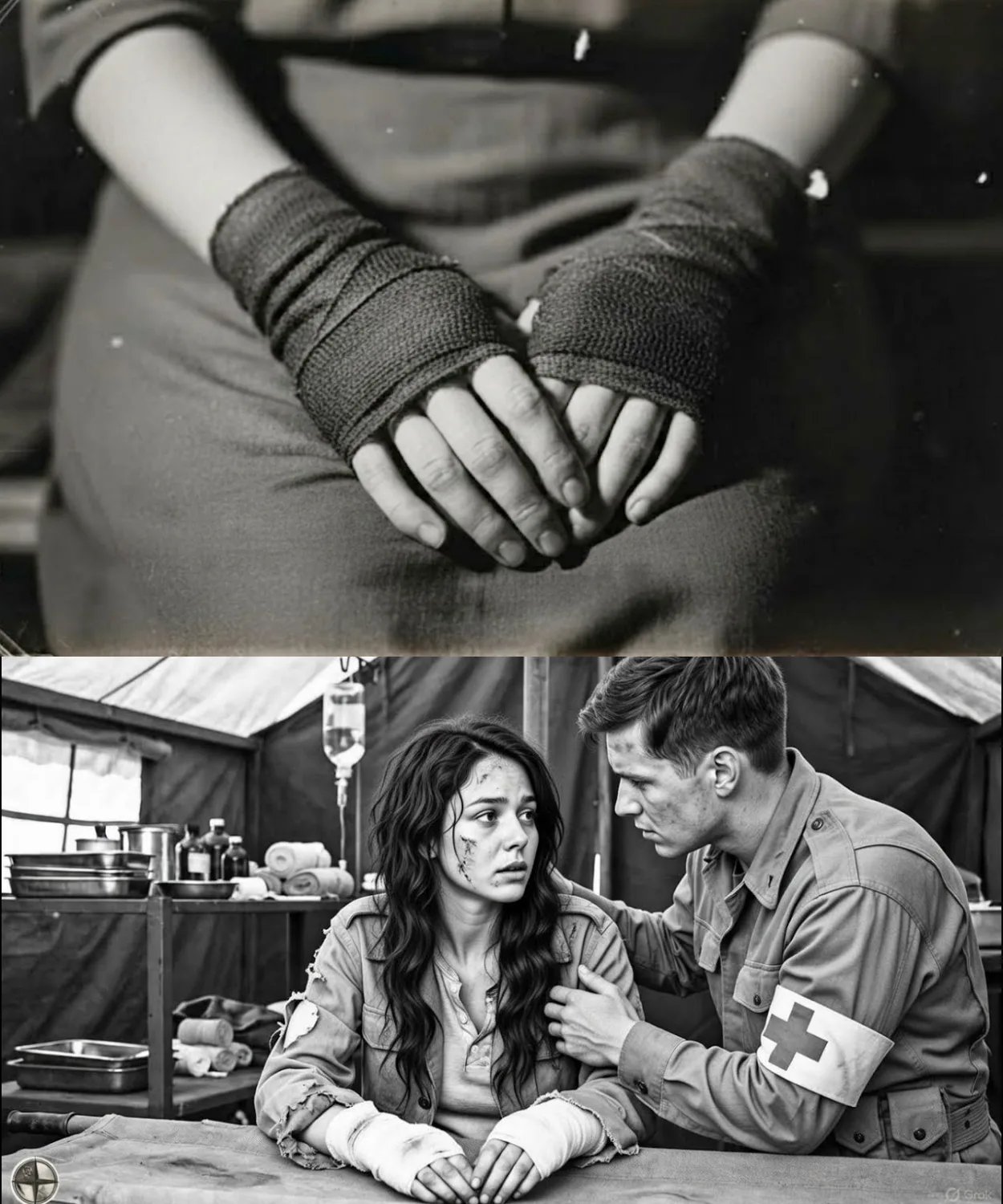

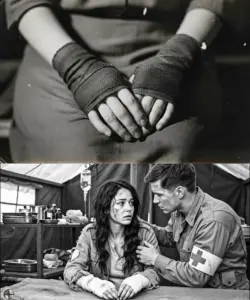

He told his interviewer, a major Patricia Holay, “I was wounded when captured.

My leg was badly injured.

I thought the Americans would leave me to die or perhaps shoot me to save ammunition.

Instead, a Navy corman worked on me for nearly an hour, using supplies and effort that seemed wasteful for an enemy soldier.

He talked to me the whole time, even though I understood no English then.

His voice was kind.

When they transported me to the hospital ship, I received surgery that saved my leg.

In Japan, such resources would never have been wasted on a lowly private.

I was nobody.

But to these Americans, I was worth saving.

The interviews revealed a pattern.

Nearly every refusing prisoner described a specific moment when their worldview had cracked.

For some, it was kindness from a captor.

For others, it was the abundance of food and medical supplies that demonstrated American industrial capacity.

For many, it was the freedom to question and discuss that they had experienced in the camps where educational programs encouraged critical thinking rather than wrote obedience.

Corporal Masau Taniguchi, a former journalist who had been conscripted into the army in 1943 and captured in the Philippines in 1944, put it most clearly.

I was raised to believe that individual thought was dangerous and that loyalty to the emperor required suppression of personal doubt.

But at the camp, I was encouraged to read, to learn, to question.

The American guards would debate politics and policies right in front of us.

They would criticize their own government openly.

At first I thought this was weakness.

Then I realized it was strength.

The strength to believe that truth could withstand scrutiny.

In Japan we were told what to think.

In America, even as prisoners, we were shown how to think.

The committee of 10 that Yamamoto had assembled prepared a formal statement carefully translated by Henry Tanaka and verified by three independent interpreters.

The document was extraordinary in its precision and its passion.

It began, “We, the undersigned former soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army, hereby state our reluctance to return to Japan at this time, not out of cowardice or desertion, but out of profound moral conviction.

We have been transformed by our captivity in ways our superiors did not anticipate and cannot understand.

We have seen the true face of America which bears no resemblance to the caricature we were taught to hate.

We have been treated with a humanity we did not extend to others when we held power.

We have witnessed a society that despite its flaws strives toward ideals of equality and dignity that our own system rejected as foreign weakness.

We can no longer in good conscience return to a nation that must rebuild not just its cities but its soul.

The statement continued for three pages, outlining specific instances of kind treatment, describing the educational programs that had opened their eyes, and requesting a pathway to remain in the United States as laborers, farmers, or in any capacity that would allow them to contribute to society while continuing to learn from American democracy.

On September 23rd, 1945, a delegation from the State Department arrived in San Francisco.

They brought with them a legal opinion from the Attorney General’s office and a directive from President Harry Truman himself, who had been briefed on the situation.

The solution was unprecedented, but pragmatic.

The refusing prisoners could not be granted immediate citizenship or permanent residency.

That would require congressional action and public debate that neither the military nor the State Department wanted to engage in so soon after the conflict’s end.

but they could be reclassified as civilian interees of interest and held in a minimum security facility while their cases were individually reviewed.

Those who could demonstrate legitimate claims such as Yamamoto’s loss of family in Hiroshima would be given special consideration or would be allowed to apply for work permits and to begin the process of integration into American society.

The catch was significant.

They would have to publicly renounce their allegiance to the Japanese emperor and sign statements declaring their intention to embrace American values.

This was not a simple administrative requirement.

For many of these men raised in a culture where the emperor was considered divine.

This was a spiritual crisis.

The committee of 10 debated for hours.

Yamamoto argued that they had already renounced their allegiance in their hearts the moment they decided not to board the ship.

Making it official was simply acknowledging reality.

Others worried about the implications for any family members still alive in Japan who might face reprisals if word got out that their sons or brothers had formally rejected the emperor.

In the end, 374 of the original 380 refusing prisoners signed the documents.

Six chose to return to Japan on the next transport ship.

Unable to take the final step of formal renunciation despite their doubts.

The story of the refusing prisoners did not make headlines at the time, the military kept it quiet, fearing it might complicate occupation policies in Japan or inflame anti-Japanese sentiment among Americans who had lost loved ones in the Pacific theater.

But within military and academic circles, it became a case study in the unexpected consequences of humane treatment of prisoners of war.

Captain Morrison, who had stood on that dock in September expecting a routine transfer, spent the next year helping to administer the program for the former prisoners.

He watched as they were dispersed to various agricultural communities throughout California, where labor shortages made them welcome despite their former enemy status.

He corresponded with many of them over the decades that followed.

In a letter written in 1967, Morrison reflected on what he had witnessed.

We did not set out to convert these men.

We simply treated them according to our laws and values, which require dignity for all persons, even enemies.

But in doing so, we won a victory more complete than any battlefield triumph could have achieved.

We showed them that the ideals we claimed to fight for were real, not propaganda.

We demonstrated that strength and kindness are not mutually exclusive.

And we proved that human beings given the freedom to think and question will often choose truth over comfortable lies.

Teeshi Yamamoto, the sergeant who had first refused to board the ship, eventually became an American citizen in 1952 after the passage of the Macarron Walter Act, which eliminated racial restrictions on naturalization.

He settled in the Sanwaqin Valley where he worked as an agricultural consultant helping local farmers implement innovative irrigation techniques.

He married an American woman of Japanese descent whose family had been interned during the conflict and together they raised three children.

In 1978, Yamamoto was invited to speak at the United States Military Academy at West Point about his experiences.

He stood before an auditorium of cadetses and told them the story of September 5th, 1945 when he had refused to go home.

“I want you to understand something,” he said to those young officers in training.

“You will be taught strategy and tactics.

You will learn about firepower and logistics.

These are important.

But the greatest weapon America possesses is not its technology or its industrial capacity.

It is its commitment to treating all human beings with dignity even in the midst of conflict.

When you capture an enemy soldier, how you treat that person matters not just morally but strategically.

Every prisoner who returned to Japan telling stories of American kindness was worth a battalion in terms of undermining enemy morale.

Every prisoner who chose to stay like I did was a vote of confidence in American ideals more powerful than any propaganda broadcast.

He paused, looking out at the sea of young faces.

I fought for an empire that told me I was superior because of my blood and my obedience.

I was captured by a nation that treated me as an equal despite my defeat and my difference.

That contradiction destroyed the world view I had been given and forced me to build a new one based on truth rather than myth.

The kindness you showed me as your prisoner was not weakness.

It was the most powerful form of strength, the strength to live according to principles even when it would be easier not to.

Of the 374 prisoners who remained, approximately 240 eventually became American citizens.

Others returned to Japan in the late 1940s and early 1950s after enough time had passed that they felt they could speak honestly about what they had learned without facing immediate reprisals.

Many became advocates for democracy and reform in postconlict Japan.

Carrying with them the lessons they had absorbed during their captivity.

The remaining prisoners, roughly a hundred men, chose to immigrate to other countries, Brazil, Argentina, Canada, seeking fresh starts away from both their homeland and the nation that had captured them.

But even these men in letters and interviews spoke of their time in American prisoner of war camps as transformative.

The SS Marine Phoenix, the ship that had waited in San Francisco Harbor that September day, made several more trips to Japan, carrying prisoners home.

But among military historians and those who study the psychology of conflict, it is most remembered for the men who refused to board and for what their refusal revealed about the power of unexpected kindness to change hearts and minds.

In the decades since, the story has been studied at militarymies and human rights institutions around the world.

It has become a case study in what happens when nations adhere to international law not just as a legal obligation but as a moral imperative.

The Geneva Conventions which mandated humane treatment of prisoners were written with the assumption that such treatment was the right thing to do.

What the refusing prisoners demonstrated was that it was also the strategic thing to do.

There is a small memorial now at the Prescidio in San Francisco placed there in 2005 on the 60th anniversary of the end of the conflict.

It bears the names of the 374 prisoners who chose to stay and it carries an inscription written by Teeshi Yamamoto before his death in 1996.

We came as enemies and prisoners, expecting death or degradation.

We found instead a nation that treated us with dignity we did not deserve, but desperately needed.

In refusing to board the ship home, we were not abandoning our heritage, but embracing our humanity.

We learned that loyalty to truth is higher than loyalty to nation, and that the courage to change one’s mind is greater than the courage to die for a cause built on lies.

The memorial sits on a hill overlooking the harbor where the SS Marine Phoenix once waited.

On clear days, you can see across the bay to where the prisoner of war camps once stood, now replaced by housing developments and shopping centers.

But the memory of what happened there remains, preserved in letters and interviews and official documents, a testament to an unlikely transformation.

The irony is inescapable.

The Imperial Japanese government had invested enormous resources in training soldiers to resist American propaganda to reject American values and to prefer death over capture.

They had created an indoctrination system designed to make their soldiers psychologically immune to enemy influence.

And it might have worked America actually been the barbaric nation described in Japanese propaganda.

But America, for all its flaws and contradictions, had something Japan’s militarist government could not comprehend.

A genuine commitment to principles that transcended national interest.

The decision to treat prisoners humanely was not a calculated strategy to win hearts and minds.

It was simply the American way, rooted in a constitution that recognized unalienable rights and a culture that, however imperfectly, strove to honor those rights.

The Japanese soldiers who refused to go home were not weak men who had been broken by captivity.

They were strong men who had been transformed by truth.

They had seen behind the curtain of their own government’s propaganda and found it wanting.

They had experienced a different way of organizing society and found it compelling.

and they had made the hardest choice a soldier can make to question everything they had been taught and to rebuild their understanding of the world from the foundation up.

In the end, the story of the refusing prisoners is not about defeat or victory in the conventional sense.

It is about the power of ideas to transcend borders and the capacity of human beings to change when confronted with evidence that challenges their assumptions.

It is about the unexpected consequences of treating others with dignity and the ripple effects that such treatment can have across decades and continents.

Those 374 men who stood on a dock in San Francisco in September of 1945, refusing to board a ship that would take them home were making a statement that echoes through history.

They were saying that home is not always where you were born, but where you are treated as you deserve to be treated.

They were declaring that loyalty is earned, not demanded.

And they were demonstrating that the human capacity for growth and change is limitless when given the freedom to think and the courage to act on conviction.

The camps where they were held are gone now, repurposed or demolished.

The men themselves have nearly all passed away, their stories preserved only in archives and memoirs.

But the lesson they taught remains vital.

That how we treat our enemies in war reveals who we truly are.

and that kindness is not a weakness to be exploited, but a strength that can transform the world in ways violence never could.

And that concludes our story.

If you made it this far, please share your thoughts in the comments.

What part of this historical account surprised you most? Don’t forget to subscribe for more untold stories from World War II, and check out the video on screen for another incredible tale from history.

Until next time.