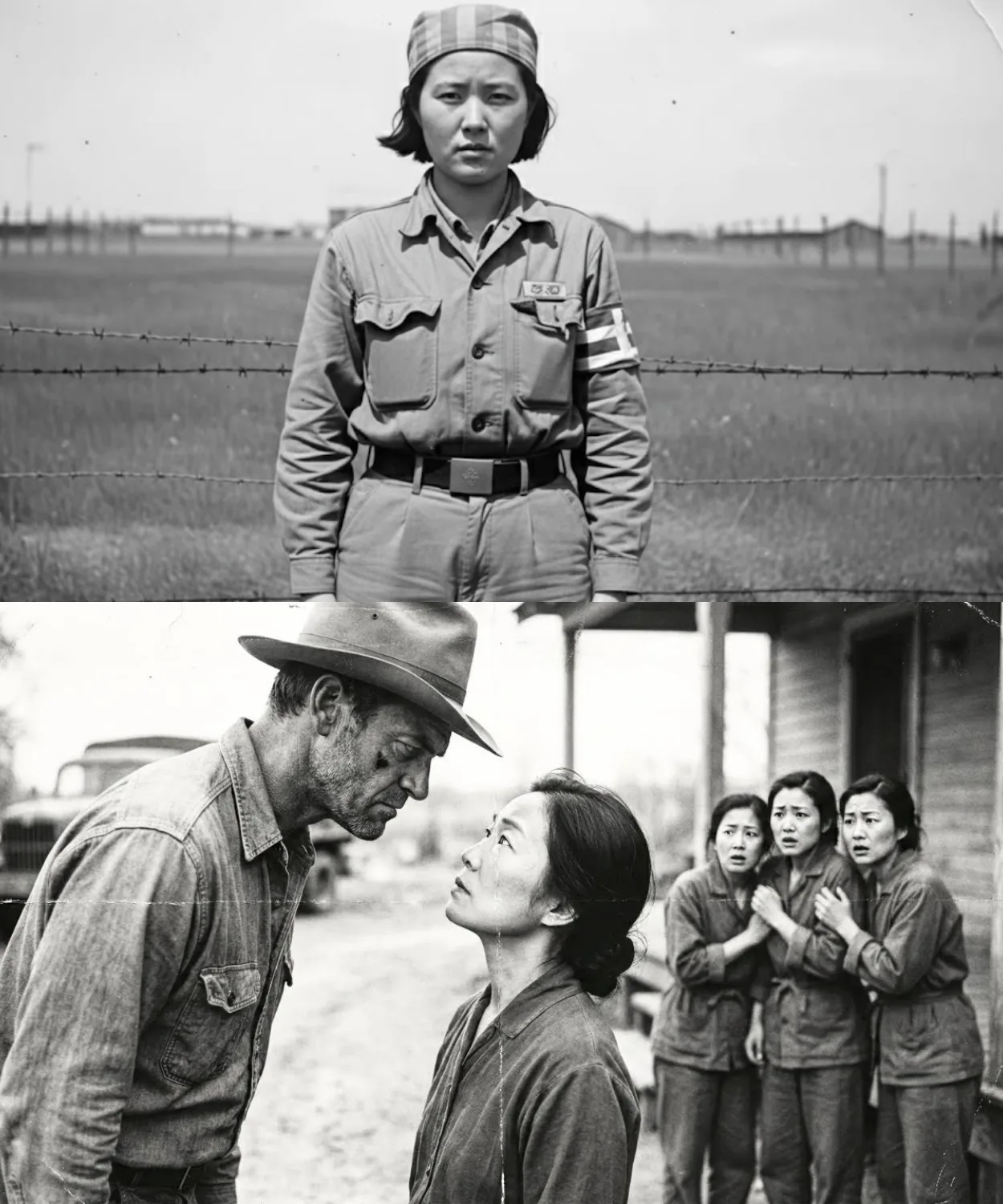

The wind kicked up dust along the dry Texas fence line, but she didn’t move.

Not for water, not for rest, not even when the sun dropped low enough to paint the sky orange behind the hills.

For 12 hours she stood like a shadow carved from war, unmoving outside the front porch of a man she didn’t know, a man who had fought people like her.

He saw her from the window three times that day, once at noon, once at supper, and again when he lit his lantern before bed.

Each time she was still there.

When he finally stepped outside, irritated, weary, he found not defiance, not apology, but something else entirely.

She wasn’t there to plead.

She wasn’t there to escape.

She was waiting because it was the only thing left she knew how to do.

And what she needed wasn’t food or freedom.

It was something much smaller and much more dangerous.

She needed to be seen.

The first time he noticed her, it was near midday.

The sun had turned the Texas dirt white hot, and the horizon shimmerred like a mirage.

From his kitchen window, the cowboy squinted, one hand resting on the sill, the other still holding a coffee mug gone lukewarm.

At first he thought she was part of the fence, a post maybe, or a tangle of brush caught in barbed wire.

But when he leaned forward, he saw the shape of a person, small, still, too still.

He thought about walking out there, maybe hollering, but something in her posture stopped him.

She wasn’t pacing, wasn’t trying to get attention.

She wasn’t even looking at the house.

She just stood, hands folded in front of her, heads slightly bowed like someone waiting for judgment.

He checked again an hour later.

She was still there.

The sun had moved, casting a thin strip of shade from the porch railing, but she hadn’t stepped into it.

She stood in the open, straightbacked, unmoving.

He couldn’t see her face clearly from the window, but the line of her shoulders didn’t sag.

It wasn’t defiance.

It wasn’t weakness.

It was something else entirely.

He returned to his work, sharpening a blade, feeding the dogs, but he kept glancing back as if making sure she was real.

By supper, his patience gave out.

The stew on the stove had boiled down too far, and he hadn’t even salted it right.

He cursed under his breath, grabbed his hat, and stepped outside.

The air hit him like a furnace blast.

As he approached her, boots kicking up little clouds of dust.

He half expected her to bolt.

PWS sometimes did, not out of strategy, but confusion, but she didn’t move.

Her eyes followed him.

Dark and unreadable, but her body stayed still.

Close up, he saw she wasn’t young, not a child, not anymore, but she wasn’t much more than that either.

Her uniform hung from her like wet cloth on a stick.

She was thin in the way that spoke of years, not days.

Thin from war, from ideology, from silence.

He stopped a few feet away.

“You lost?” he asked, not unkindly.

“She blinked.

The question might as well have been a stone tossed into a river.

Ripples, but no reply.

He tried again, slower.

You need something? For a long time, she didn’t answer, just stared.

And then, almost too soft to hear, she raised one hand and pointed, not at the house, not at the door, but at the small threadbear cuff of her left sleeve.

It was torn open, fraying like an old flag.

She reached into her other hand and opened her fingers.

Nothing inside, just the shape of what should be there.

Then she spoke.

One word.

Careful.

Needle.

The cowboy blinked.

Of all the things he’d expected, food, water, permission, maybe even some protest.

He hadn’t expected that.

A needle, not a favor, not an escape, a tool.

She looked down, then back up.

her face unreadable, but her voice didn’t shake.

So he stared at her at the tear in her uniform, the one small rebellion against the falling apart of everything.

It wasn’t about clothing.

It was about control, about trying to mend in this dry and foreign place, the last thing she could still claim as hers, her sleeve, her hands, her dignity.

He looked over his shoulder toward the barn, where his mother’s old sewing kit still sat somewhere on a shelf, untouched for years, then back at her.

The dust caught in the wind between them, but neither moved.

“All right,” he said finally.

“Wait here.” She didn’t nod, didn’t smile, just stood there, waiting as if she’d known all along he would understand.

She did for nearly another hour.

When he returned, she was still standing in the same spot, the wind catching her skirt just enough to lift its edge like a page being turned.

In one hand he carried an old tin of buttons, thread, and needles, rust specked, and half forgotten in a drawer his mother hadn’t opened in years.

In the other, a glass of water slick with condensation.

As he held it out to her, she hesitated, not in fear, in disbelief.

Her eyes flicked from the glass to his face, back to the glass, then to the door of his house behind him, as if checking for the trick.

Then slowly she took it.

Her fingers brushed his as they closed around the glass, and she pulled back like she’d touched a live wire.

She drank quickly, not out of thirst, but to be done with it.

Her eyes didn’t leave his.

She handed the glass back with both hands and then bowed just slightly.

Just enough.

He didn’t know what to do with that.

She didn’t either, because nothing about this matched what she had been told.

In Japan, before the surrender, her instructors had said the Americans would hurt them.

They would violate them, strip them of their names, their skin, their history.

Surrender was worse than death.

It was eraser.

At the hospital where she’d worked as a Tintai assistant, the nurses whispered that capture meant dishonor so complete your family would disown your memory.

She had seen photos or fakes that were passed around like warnings of women mutilated, humiliated.

The message was clear.

If you are caught, you are nothing.

And yet here she stood in a dusty Texas field with a needle in her hand and water in her stomach.

Not a single blow, not a single insult, no barked orders, no learing faces, just this man, this cowboy, this silence.

He watched her with the same weary confusion.

He’d fought in the Pacific, not on the front lines, but close enough.

He’d seen what the war had done to bodies, to minds.

He had been told stories, too, that they would never surrender, that if they smiled, it was because they were hiding a knife.

He’d heard of booby traps hidden on corpses, of women with grenades strapped to their chests.

That was what he expected when the trucks rolled in with female PS.

Defiance, fire, hatred.

But not this.

Not the way she stared through him, not like an enemy, but like a puzzle.

The air between them thickened with heat and history.

The sun burned straight overhead now, blistering and unforgiving.

A cicada droned in the grass.

Neither of them moved for a long time.

She turned her attention to the thread in the tin, running her fingers across the spools, eyes narrowing, lips pressed tight in concentration.

He cleared his throat, unsure whether to speak again.

She spoke first.

“Ariatu,” quiet, almost embarrassed, he tipped his hat slightly.

“Yeah,” he muttered.

“Sure.

” Then he stepped back toward the porch, paused, and set the glass on the rail.

She remained where she was, kneeling now, the kit opened before her like an altar.

He watched her thread the needle, her movements sharp with purpose.

Each stitch she pulled through her sleeve was deliberate, not to fix the fabric, but to remind herself she could.

For the next hour they didn’t speak.

He sat on the porch with his boots up.

she mended in the dirt.

The distance between them was only a few feet, but it held oceans, languages, dead fathers, bombed cities, and rumors neither could forget.

And still the silence held, not as a wall, but as something waiting to be understood.

Before she had ever seen a cowboy or tasted American water, her world had already been cracked in half.

She grew up in the industrial shadows of Nagoya, not on the main streets, but in a cramped wooden house that leaned as if it too was tired of war.

Her father worked in a machine shop until he was conscripted in the early years of the conflict.

The last thing he ever mailed home was a drawing of a sunrise, two red brush strokes with no words.

The next came in a white envelope edged in black, delivered by a man who bowed and did not meet her mother’s eyes.

After that, there were no more drawings, only ration cards, radio broadcasts, and the slow, quiet unspooling of color from everyday life.

She learned to make rice stretch farther than it should, learned to boil roots and weeds into something that could pretend to be dinner.

learned the sound of an air raid before the sirens.

The wind changed first, then the silence, then the bombs.

She did not cry during the raids.

She learned not to.

Crying drew attention.

Crying marked you as weak.

When the Tatent Thai recruiters came to her school, all pressed uniforms and practiced speeches.

They spoke not of survival, but of sacrifice, of honor, of service.

The pamphlets were crisp, the slogans sharp.

Girls like her were told they would be the spine of the homeland, the invisible hands behind victory.

She believed them.

At 14, she was sent to a field hospital outside Osaka.

Her duties were simple.

Clean, carry, keep quiet.

The men she helped had no faces she would remember, just wounds, missing limbs, burns, screams that never made it past clenched teeth.

The nurses whispered to her in the halls, “Don’t speak unless ordered.

Don’t ask questions.

Don’t expect thanks.

” They handed her a brush and a bucket before they ever handed her a spoon.

They also gave her something else.

rules, not laws, not policies, rules of spirit.

Never allow yourself to be touched by the enemy.

Never surrender your name.

Never expect rescue.

The emperor was watching.

Always to live through capture was to shame your ancestors.

If capture came, there were pills.

Or the ocean.

She believed that too.

But belief does not hold forever against hunger.

When the emperor’s voice finally reached her ears, scratchy and distant over a smuggled radio, it didn’t sound like divinity.

It sounded tired, small.

He told them to endure the unendurable, that the war was lost.

The nurses sat down where they stood.

One wept into her sleeve.

Someone vomited.

Kiomi did not cry.

She folded her apron, placed it on a metal cot, and walked outside into the stillness of a world no longer at war, but not yet at peace.

What followed was a blur.

Trucks, corridors, barbed wire that came and went like breath.

Other girls, all silent, all with the same questions buried behind their eyes.

The Americans didn’t scream.

They didn’t strike.

They processed, labeled, moved them like freight.

She had been prepared for pain.

She had not been prepared for indifference.

The ship that carried her across the Pacific smelled of salt and diesel.

The bunks were lined in rose.

She shared a space with a girl who used to sing in her sleep, then stopped altogether.

They were fed, not much, but enough to be confusing.

The sea churned beneath them, but inside everything was still.

She did not understand how she had survived.

She did not know if survival was even what this was.

All she knew was that the world she had been raised to believe in had collapsed.

Not with fire, but with silence.

And now here she was on the other side of the world, mending a torn uniform under a sky that did not belong to her, wondering who she was if the war was over and she had not died.

The truck that carried her into the ranch coughed and sputtered as it rolled to a stop, dust curling up around the wheels like smoke from a dying fire.

The doors opened with a sharp clang, and the women inside did not move until ordered.

Kiomi was the third to step down, boots thudding into unfamiliar dirt.

The Texas wind smelled of manure, sweat, and hay, a smell so far from the ash and antiseptic of the hospital wards that it stunned her.

She looked up.

There were no barbed wire fences here, not like the ones she’d seen during processing.

just open fields, a sagging barn, cattle moving slow and stupid in the heat.

The sky stretched so wide it felt like a trick.

For a moment she wondered if this was even captivity at all.

Then she saw the men.

They stood by the barn, rifles slung not across their chests, but hanging loose at their sides like afterthoughts.

These weren’t soldiers in pressed uniforms.

These were cowboys.

One wore a battered hat.

Another had a piece of straw in his mouth.

Their faces were unreadable.

Not cruel, not kind, just curious.

The American who called the role did so with a clipboard and a pencil, squinting as he mispronounced the Japanese names.

Each name fell into the dust like a forgotten thing.

When Kiomi’s turn came, she didn’t answer.

Another woman translated for her, and the man scribbled something beside it.

They were shown to the barracks, which looked more like horse stalls repurposed with cotss and army blankets.

The floor was swept clean.

The air inside was warm, not cold.

It wasn’t punishment.

It wasn’t comfort.

It was something in between.

She said little.

At night, while the others whispered to each other or stared at the walls, Kiomi sat by the edge of the stall door and looked out.

Not at the stars, not at the sky, but at him, the same cowboy, always leaning on the far fence post just before nightfall.

He never looked at them, never wandered close.

He’d roll a cigarette, light it, and stare out at the pasture like he was waiting for something to return.

Sometimes he’d hum low, tuneless, and she found herself listening, not because she liked the sound, but because it was the only one that didn’t make her flinch.

She never spoke to him, not then, but she watched.

The way he wiped sweat from his brow with the back of his hand.

The way he tilted his head when listening to the cattle.

The way he walked like a man used to silence.

In a world where every male figure she had known barked, ordered or ignored, his quiet disinterest felt like a kind of mercy.

The other women adjusted in their own ways.

Some grew louder, others more withdrawn.

A few tried to charm the guards with broken English or awkward smiles.

Kiomi didn’t.

She folded her blanket every morning.

She swept the corners of the stall.

She ate only what was given, never more.

And each night, without fail, she sat with her knees drawn up to her chest and watched the man on the fence line.

She did not know why, only that watching him felt like remembering something that hadn’t happened yet.

He brought her a stool, not because she asked.

She hadn’t moved in hours, and something about the way she held herself, stiff but not stubborn, made him uneasy.

She looked like someone holding her breath under the weight of something no one could see.

So he went back inside, grabbed a three-legged wooden stool from the corner by the fireplace, and brought it to her.

Held it out like an offering.

She didn’t take it.

She didn’t even blink.

She was still kneeling in the same place, dust soft around her feet, the light of the setting sun turning the fabric of her uniform the color of rust.

Her hands were folded in her lap, fingers loose, but ready.

He placed the stool beside her anyway, then cleared his throat.

“You want to come inside, eat something?” he asked, voice low.

She didn’t look at the stool, didn’t look at him.

Her eyes instead were fixed just above his heart.

He glanced down, confused, his shirt pocket.

She was staring at the faint outline of a button and the frayed stitch beneath it.

He followed her gaze, puzzled, and waited for her to speak.

Then, at last she did.

Needle, she said.

The word was soft.

Not pleading, not embarrassed, just stated.

He furrowed his brow.

A needle? She nodded and then lifted her arm.

Her left sleeve had torn open at the seam, the edge curling like paper burned at the ends.

The threads had come loose in transport weeks ago.

It dangled, flapping slightly in the breeze.

She didn’t touch it.

She just held her arm up so he could see.

This was what she’d waited for.

Not food, not permission, not even safety, a needle.

Because it wasn’t just a uniform.

It was hers.

The only thing she’d brought with her across an ocean of silence.

The only thing that hadn’t been taken, reassigned, or burned.

It still had her name sewn on the inside, faded by sweat.

A sleeve might seem like nothing to a man who had closets, but to her it was the last thing she could fix with her own hands.

He looked at the sleeve again, then at her.

The stiffness in her back wasn’t pride in the way he understood it.

It was survival, control.

Even if all she had left was one tattered cuff, she would not let it unravel.

He scratched his chin, muttered something under his breath, then turned on his heel and walked toward the barn.

Inside, past the saddles and feed bins, under a stack of old canned peaches and mouse chewed hymn books, he found it, his mother’s sewing tin, dent in the lid, a dull brass thimble inside, spools of thread wound tight around wooden pegs and needles, dozens of them.

When he brought it back out, he didn’t hand it to her.

He set it down slowly, opened the lid, and stepped back.

She looked inside as if staring into a temple.

Her fingers hovered over the contents for a moment before selecting a needle, then black thread.

She did not hesitate.

She bit the thread clean, tied it in a knot, and threaded it in a single motion.

Then she lowered her head and began to stitch.

He sat on the porch watching, not speaking.

The sun dipped lower, the sky went soft, and across the dirt she worked, quiet, precise, whole.

He understood now.

She had not come to be saved.

She had come to sew.

The barn was cooler than the porch, the thick wooden walls holding back the worst of the day’s heat.

He found her sitting cross-legged on the packed dirt floor, lantern light pooling softly around her like a small private world.

The sewing tin lay open beside her, its contents arranged with care.

Needle, thread, thimble.

The torn sleeve rested across her knees, pulled taut between her fingers.

Her hands trembled just slightly.

Not enough to slow her, not enough to ruin the line of the stitch.

Each movement was deliberate, practiced as if her body remembered something her mind had nearly lost.

Push the needle through, pull, tighten, pause, breathe.

The rhythm was steady, almost ceremonial.

He leaned against the barn door and watched without announcing himself.

The silence felt different in here, thicker, not empty.

It wasn’t the silence of fear or waiting for an order.

It was the kind that settles when words would only cheapen what’s happening.

For her, this wasn’t mending cloth.

It was restoring a boundary.

The world had taken so much from her without asking.

Names, roles, futures.

Sewing was one of the few acts left that still belonged to her alone.

No command attached, no reward expected, just the simple truth that she could still make something whole.

As the needle moved, memories rose uninvited.

She saw her brother’s uniform years earlier laid out on the tatami floor.

He had been too thin then, too proud to say goodbye properly.

She remembered kneeling beside him, sewing a loose button back onto his sleeve while he pretended not to watch.

Her mother had hovered nearby, pretending to busy herself with tea she never poured.

When she finished, her brother flexed his arm and smiled, a rare boyish thing, and said it felt stronger now.

That memory tightened her throat.

She stitched more carefully after that, as if the thread might carry him back.

The cowboy shifted his weight, the old wood creaking under his boots.

He felt like an intruder in a sacred space, though he couldn’t have explained why.

He had seen men clean guns with less reverence than the way she worked that needle.

He had grown up watching his mother mend socks by lamplight, humming to herself, the house safe and whole around them.

He hadn’t thought about that in years.

He turned away briefly and poured coffee into a tin cup, the smell rich and bitter in the cool air.

He set it down beside her without a word.

She noticed it.

Of course she did.

But she didn’t reach for it.

Not yet.

The stitch wasn’t finished.

She pulled the thread through one last time, tightened it with a careful tug, and tied the knot so small it nearly disappeared into the seam.

Only then did she lower her hands.

Only then did she exhale fully, shoulders softening as if something inside her had finally loosened its grip.

She ran her fingers along the repaired sleeve, smooth, whole.

Then she reached for the cup.

She didn’t drink right away.

She held it, warming her palms, letting the steam rise against her face.

When she finally took a sip, her eyes closed, not in pleasure, but in acknowledgement.

coffee,” she said quietly, testing the word like a new stitch.

He nodded.

“Yeah.” They sat like that for a long while.

Lantern light, cooling earth, the quiet presence of animals breathing in their stalls.

Two people who had been taught to fear each other, now bound by the simple fact of shared silence.

There was no forgiveness spoken, no absolution.

But something had shifted.

He understood now that her waiting hadn’t been passive.

It had been intentional.

She had waited because she knew what she needed, and she knew it could not be demanded.

And she understood, though she would never put it into words, that this man had seen her not as a symbol or a burden, but as someone capable of fixing what was hers to fix.

The war had taught them both how to destroy.

This moment taught them something quieter.

Later that night, she returned to the fence.

Not the one circling the ranch, but the short wooden line separating the cowboy’s porch from the open field.

It had no barbed wire, no guards, just two posts and a rickety beam where the land seemed to pause before deciding what came next.

She sat beside it, her knees drawn to her chest, arms around them, the sewing tin resting quietly at her side.

He noticed her from the window.

The stars were already out, dust swirling like smoke under the porch light.

For a moment he considered going to bed, pretending this wasn’t his concern.

But something in her stillness drew him.

He stepped outside, not speaking.

In his hand was a chair.

He didn’t offer it.

That would have required words neither of them had.

He just set it down beside her.

A respectful distance.

Then he sat.

They said nothing.

He didn’t ask questions.

She didn’t offer answers.

But inside her a storm.

She had prepared her whole life for brutality.

Had been taught that surrender was the end of self.

and that American soldiers were not men but monsters draped in fabric and fire.

When she was shipped across the sea, she expected cruelty, expected shouting, grabbing, punishment.

She thought she might be forced into labor, stripped of her dignity, erased quietly among strangers who would never care to know her name.

Instead, she had been handed a needle.

She could not explain that.

Even now, hours after the fact, it made less sense than anything else in her captivity.

He had seen her broken sleeve and fetched a tin of tools, not to fix it for her, but so she could do it herself.

He hadn’t looked at her with pity.

He hadn’t demanded thanks.

He’d just seen her.

It was a crack in everything she’d believed.

Kindness, she had been told, was a trick, a prelude to pain.

But this this had no transaction, no condition, no cruelty hiding underneath, and that made it harder to understand.

The cowboy leaned forward slightly, forearms resting on his knees, hat tilted low.

He didn’t fidget, didn’t glance at her, just breathed the same air and waited.

That too confused her.

If he had tried to talk, tried to understand her, she could have shut it down.

She had walls for that.

But silence, silence gave her no enemy, only herself.

So she sat with her thoughts, watching them unravel like threads she couldn’t gather fast enough.

What if surrender hadn’t meant what she thought? What if mercy wasn’t a trap? What if everything she believed about enemies, about herself, had been shaped by people who had never left the island? She glanced sideways, eyes flicking to the man beside her.

His boots were dusty, his hands calloused.

He had probably fought in a war, too, though no one had told her that.

Maybe he’d lost someone.

Maybe not.

But he hadn’t lost himself.

That scared her more than any weapon, because if he wasn’t the monster, then who was she now? What name did she have left? She gripped her knees tighter, the fabric of her mended sleeve brushing her cheek.

It was the only thing she trusted at that moment, the stitch she had made, the one line she could still trace as hers, and yet even that had come from him, or at least through him.

She exhaled slow, shaky.

The cowboy shifted slightly and spoke just once.

“Long day,” he said.

She nodded.

Then, as if the words surprised her as much as they did him, she replied, “Yes, that was all, but it was enough.

” The night deepened.

Somewhere in the field, a horse snorted, an owl called, and two enemies sat side by side, watching a world that suddenly made no sense, and quietly, unwillingly, began to make a different kind.

She began the letter the next morning, not at a desk, not inside the barracks.

She sat on the porch, the same place she had waited the day before, the wood warm beneath her legs, the horizon open and unguarded.

The cowboy had left a pencil and a few sheets of paper on a crate by the door without saying anything.

He did not watch her take them.

He did not instruct her how to use them.

He simply went about his work, trusting that if she wanted them, she would.

She stared at the blank page for a long time.

The first sentence did not come easily.

Words had always belonged to others, officers, radios, posters nailed to walls.

She had learned to listen, to obey, to absorb.

Writing in her world was something done by men in uniforms, not by women who cleaned blood from floors.

The pencil felt strange in her hand, heavier than it should have.

She pressed the tip to the paper and lifted it again, afraid of leaving the wrong mark.

Finally, she wrote slowly, carefully, each character shaped as if it might be judged.

They do not hurt us.

She stopped, read it again.

It felt dangerous to write, not because it was false, but because it was true.

She had been taught that truth was not something to be recorded unless it served the empire.

This truth did not.

It unraveled it.

She added another line.

They let me sew.

That was all for that day.

Two sentences.

She set the pencil down and folded the paper once, then again, as if the words might escape if left exposed.

Her hand trembled, not with fear, but with the weight of what she had admitted to herself.

The porch became her place after that.

Not a boundary, a choice.

She returned to it in the afternoons, sometimes with the sewing tin, sometimes with nothing at all.

She no longer waited because she had nowhere else to go.

She waited because the space allowed her to exist without instruction.

The cowboy would pass by, tip his hat, leave a cup of coffee or a folded blanket.

Sometimes he sat, sometimes he didn’t.

The waiting was no longer obedience.

It was permission she gave herself.

She stitched again that evening, repairing another seam, reinforcing a hem.

Each stitch was small, almost invisible, but together they changed the way the fabric rested on her body.

She noticed how standing felt different when the sleeve no longer pulled, how movement returned when nothing snagged.

These were small victories, but they were hers.

As she worked, questions pressed in.

If the enemy offered thread instead of chains, what had the war been for? If dignity could be restored with a needle and a few inches of cotton, why had she been taught to die rather than surrender? She remembered the pamphlets, the speeches, the certainty with which men had told her who the enemy was.

None of them had mentioned this.

None had warned her about the confusion of kindness, or the way it could slip inside you and rearrange everything.

Cruelty was easy to resist.

Kindness demanded answers.

She added to the letter over the next days.

Never long paragraphs, just fragments.

observations.

The food is warm.

They do not shout.

I am not afraid when I sleep.

Each line felt like a small rebellion, not against America, but against the lie that she was worth nothing unless she died properly.

The cowboy read nothing.

He did not ask.

He understood, perhaps without knowing how, that this was hers.

By the end of the week, the porch had become something else entirely.

Not a place of arrival, a place of becoming.

She sat there with her back straight, shoulders relaxed, eyes no longer fixed on the ground.

The waiting had changed shape.

It was no longer empty time.

It was time reclaimed.

She folded the finished letter and held it in her lap.

She did not know if it would ever reach Japan.

She did not know how it would be received.

But for the first time since the war began, she knew why she was writing.

Not to report, not to confess, but to exist on paper in her own words.

Are you finding this story as powerful as we do? If so, like the video and leave a comment below telling us where in the world you’re watching from.

We’d love to hear your thoughts.

She noticed the ribbon before she noticed the girl.

It was early, the kind of quiet Texas morning, when the sun hadn’t yet burned the dew from the porch steps.

The prisoner sat cross-legged again, hands in her lap, letter folded beneath her thigh, as if afraid the wind might take it.

Then the sound, not boots, but soft sold shoes.

She turned slowly.

There, standing at the edge of the porch, was a girl, barely out of childhood, brown braid, freckles, a dress that looked handmade.

She held no weapon, no tray of food, just a small red ribbon folded neatly in her palm.

The P woman blinked, unsure.

The girl didn’t speak.

She didn’t step closer.

Didn’t offer it with ceremony.

She simply placed it beside the woman on the worn wooden plank and stepped back.

Their eyes met only briefly, enough to see each other, not enough to intrude, and then the girl was gone, her soft footsteps fading into the rustle of morning chores.

The prisoner stared at the ribbon.

It was vivid against the dust gray world, red like lacquered wood in a coyoto temple, red like the armband her brother wore when he left for Manuria.

But it held no insignia, no command.

It was just fabric, light, useless by military standards, and it had been left without demand.

She didn’t touch it at first.

She only looked.

Then, after several minutes, her hand moved.

Not a reach, a hover, a slow curl of fingers, as if testing whether she was allowed.

When her skin met the fabric, she startled at its softness.

Not silk, but close.

She turned it over in her hand, folded it, unfolded it.

There was no note, no explanation.

By midday, the ribbon was still in her palm.

When the cowboy passed by with an arm full of feed sacks, he glanced down and nodded at her.

She gave the faintest bow, almost imperceptible, and then returned her eyes to the cloth.

Later that afternoon, when the sun slanted golden across the porch, she stood.

She didn’t walk away.

She didn’t call attention.

She simply stood, brushed the dust from her skirt, and began to gather her hair.

Her fingers were methodical, twisting the strands back the way she used to for temple visits as a girl.

It took several tries.

She hadn’t done this in years.

When the knot held, she paused.

Then, with the same care she had used to stitch her uniform, she tied the red ribbon around it.

Not too tight, just enough to stay.

She sat again, this time with her spine taller.

She felt the breeze tug at the bow.

It was not for vanity.

There were no mirrors here, no audience.

This was not about looking pretty.

It was about something else entirely.

It was about contrast.

The military uniform on her shoulders, patched, but whole.

The ribbon in her hair, defiant in its softness.

One spoke of order, obedience, lost wars.

The other whispered of something she’d forgotten existed.

Choice.

The cowboy’s daughter saw her later from the window.

The ribbon danced in the wind like a flag, but one that pledged loyalty to no one.

When the cowboy asked his daughter why she’d left it, the girl only shrugged.

“She looked like she needed it,” she said.

“And maybe she had.” The woman who had stood 12 hours in silence beneath the Texas sun, too afraid to ask for a needle, was gone.

In her place sat someone else, not American, not entirely Japanese, but something being stitched together, one silent gesture at a time.

Weeks passed, and the wind began to change.

The days got shorter, the heat softened, and with it the quiet routines that had become familiar began to fray.

Orders came down, as they always did, from places far removed from this dusty patch of Texas soil.

The women were to be moved.

No explanation, no promise of what came next, just movement again.

The morning of departure was uneventful.

No grand ceremony, no salutes, just the sound of boots on gravel and canvas bags tossed into the back of a rumbling army truck.

The P women lined up with practiced discipline, their uniforms now a patchwork of repairs, dignity sewn in thread.

She stood among them, same frame, same posture, and yet somehow no longer the same.

The cowboy stood on his porch, arms crossed, leaning on the rail.

He hadn’t said goodbye the night before.

Neither had she.

That wasn’t their way.

When she reached the open truck bed, she paused.

The other women climbed in, but she turned slowly, their eyes locked.

He gave no wave.

She offered no smile, but then a single bow.

Not deep, not submissive, just enough to say, “I saw you.

You saw me.” And that was enough.

He didn’t nod.

He didn’t move.

But inside, something shifted.

He had spent weeks trying to figure out why she’d waited outside his house, why she’d endured the sun, the silence, the stillness.

He thought maybe she needed food, shelter, some mercy only he could offer.

But that wasn’t it.

It had never been about the fence.

It wasn’t even about him.

She hadn’t waited for salvation.

She had waited to reclaim something no one had offered her since the war began.

The right to be seen.

Not as a number, not as an enemy.

Not even as a victim, but as a whole human being.

He realized then that she had never once asked for rescue.

All she needed was space.

space to mend, to exist, to breathe without having to apologize for it.

The truck jolted forward.

Dust rose.

He watched until it disappeared beyond the bend in the road, until even the sound of its engine dissolved into the wind.

Inside the barn, the stool she had once sat on still leaned against the wall.

A loose thread from her uniform lay curled on the wooden floor.

He picked it up, thin, faint, but intact.

She had arrived a ghost, silent, watching, waiting.

But she left a woman, not whole, perhaps, but real.

Defined not by her wounds, but by her will.

He never learned her name.

She never learned his.

And maybe that, too, was part of the strange truth of it.

that sometimes the deepest recognitions happen not in shared language but in the space between words.

If this story moved you, please like the video and comment below where you’re watching from.

Thank you for helping us remember the forgotten echoes of

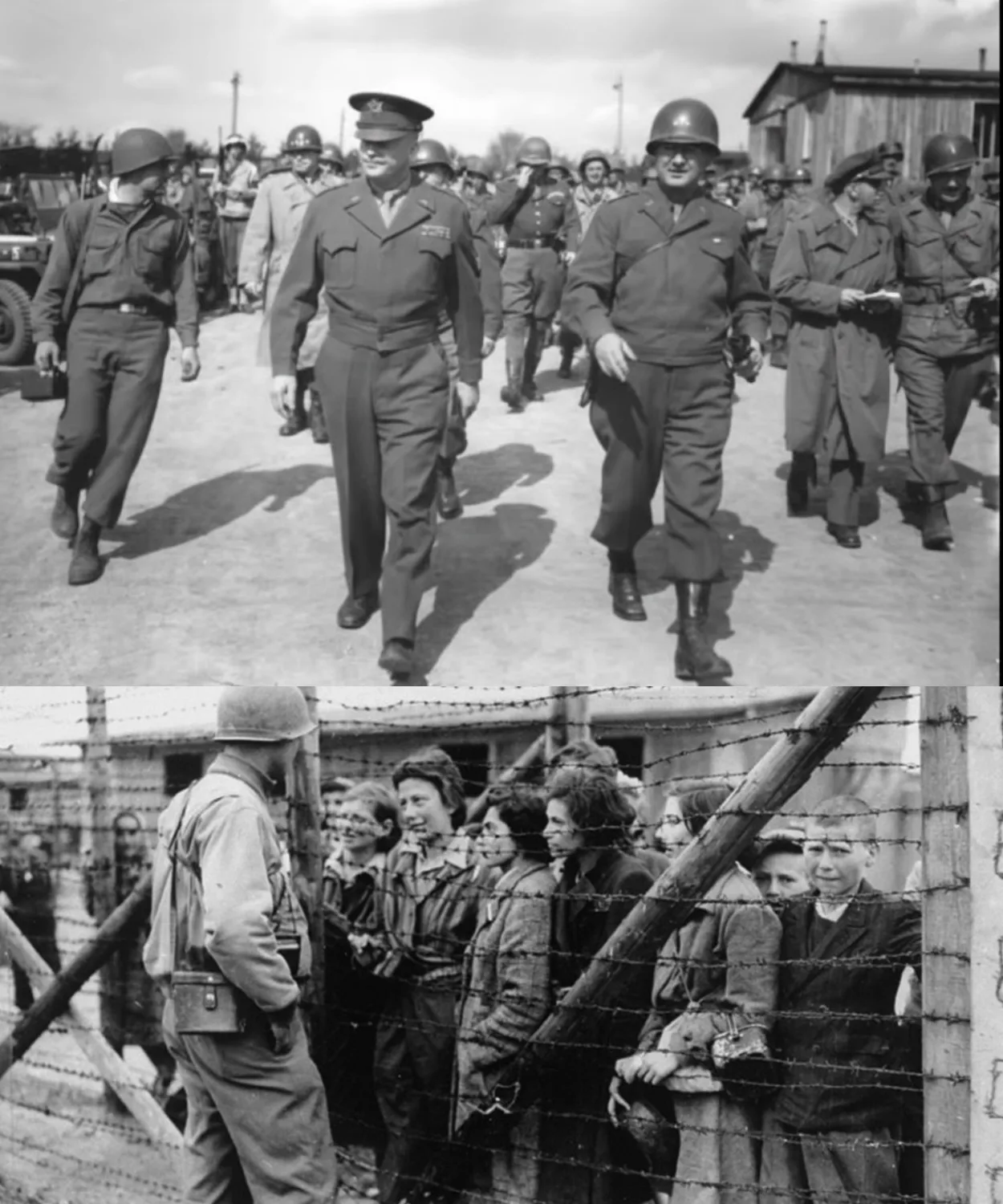

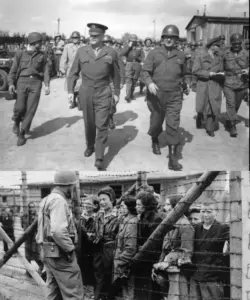

February 1945, the war was almost over, but 87 German women sat freezing in a prison camp in Belgium, waiting to see if the Canadian soldiers guarding them would leave them to die in the snow.

They had been told their whole lives that the enemy would show no mercy, especially to German women.

Now, as the coldest winter in decades gripped Europe and a massive blizzard headed straight for their camp, they were about to find out if everything they believed was true or a lie.

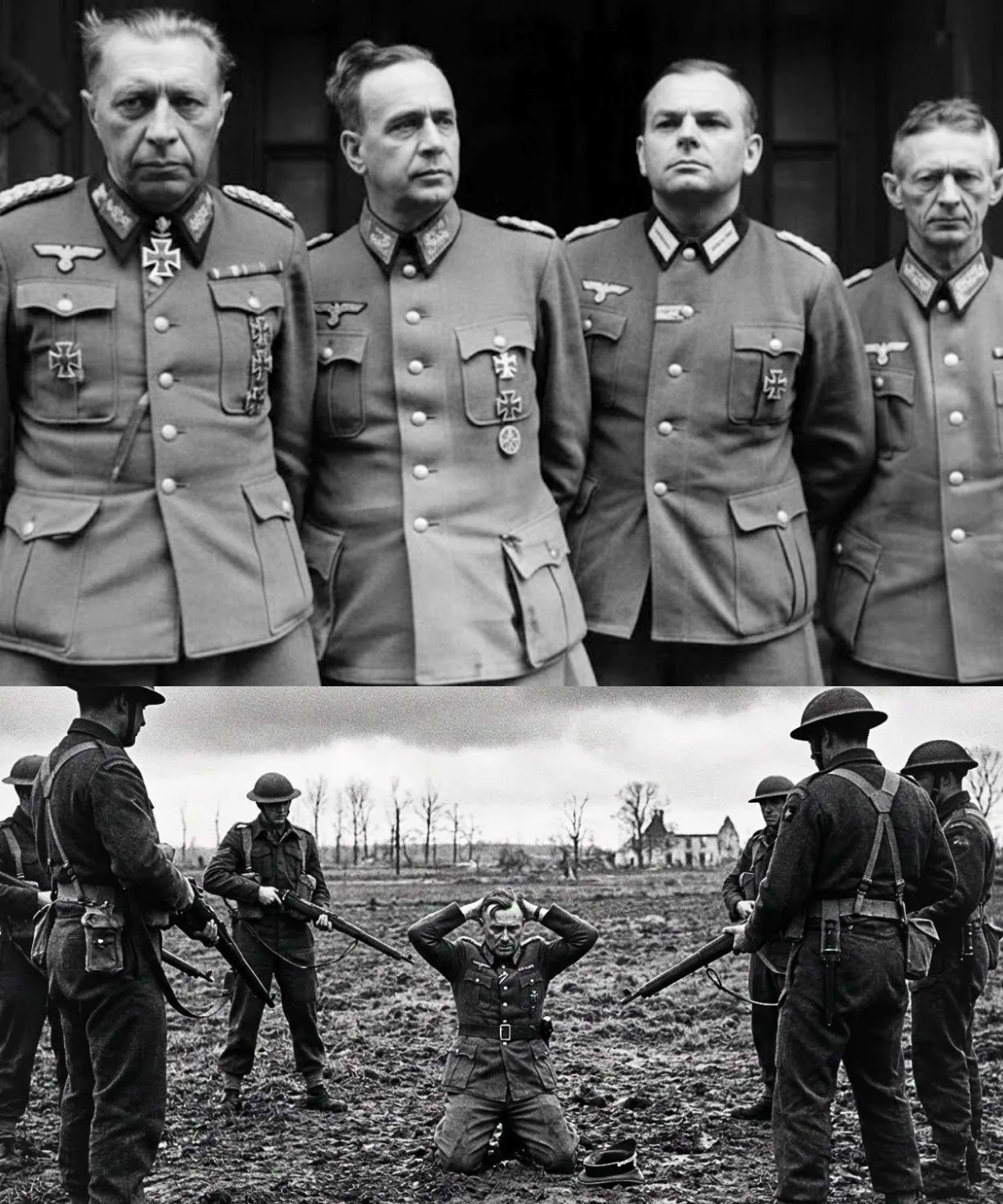

Germany was falling apart.

The Allied armies were pushing deeper into German land every single day.

Cities that once stood proud were now piles of broken stone and ash.

The Nazi government that promised victory was now running and hiding.

Food was gone.

Medicine was gone.

Hope was gone.

Across Northern Europe, the temperatures dropped to 15° below zero.

Supply trucks could not get through the snow.

Train tracks were bombed and twisted.

Roads disappeared under ice and frozen mud.

People were starving in the streets.

Soldiers were surrendering by the thousands.

And in the chaos of retreat, these 87 women had been captured.

They were not regular soldiers.

They were nakta heler inan which meant signals helpers.

They had worked in communications for the vermach sending messages operating radios and keeping the German military connected.

They were young between 19 and 34 years old.

Many had joined because they believed in their country.

Others joined because they had no choice.

Some came from nice families in Berlin and Munich.

Others grew up on small farms where they never had enough food even before the war.

But now none of that mattered.

They were prisoners and they were enemy combatants and winter did not care about their stories.

The makeshift prison facility where they waited was never meant to hold people through winter.

It was just a collection of old storage buildings with thin wooden walls and broken windows.

The wind cut through every crack.

At night, the women huddled together on the cold floor, sharing the few thin blankets the Canadians had given them.

Their breath made clouds in the freezing air.

Some women had frostbite on their fingers and toes.

The pain was constant and sharp.

They survived on 400 calories each day, which was about two small potatoes and a piece of bread.

Before the war, a working woman would eat 2,000 calories.

Now, their stomachs hurt all the time from hunger.

Their bodies were weak.

Their uniforms were falling apart.

Many did not have proper winter coats.

Some wrapped themselves in old newspapers to try to stay warm.

These women had been forced to march for days before they were captured.

The German army was retreating so fast that they left people behind.

The women walked through snow and mud with almost no food.

Their feet bled inside their broken boots.

When the Canadian soldiers finally found them, they were more than happy to surrender.

Anything was better than walking through the frozen countryside with no help coming.

At least in the camp, they had walls around them and a roof, even if it leaked.

At least they were not being shot at anymore.

But the Nazi propaganda had filled their heads with terrible stories.

For years, they heard that the Canadians and Americans and British were monsters.

The propaganda posters showed Allied soldiers as cruel beasts who would hurt German women and children.

The radio broadcast said the enemy would torture prisoners.

Teachers in school told them that surrender meant death.

Even their own officers warned them before they were captured.

If they catch you, they will show no mercy.

One lieutenant had said, “They will use you and then throw you away like garbage.

” The women believed it because it was all they had ever heard.

When you hear the same lie a thousand times, it starts to sound like truth.

Now they sat in that cold camp, and they waited.

The guards were mostly young Canadian men, some barely older than the women themselves.

The guards brought them food and water.

They did not hurt them.

They did not yell or threaten, but the women still watched them with fear.

They did not trust the kindness.

They thought it was a trick that the real cruelty would come later.

At night, they whispered to each other.

They are waiting,” one woman named Greta said.

“When we are no use to them, that is when it will happen.” The others nodded.

They all felt it.

The fear lived in their chest like a heavy stone.

Then the camp commander received the weather report.

A massive blizzard was coming.

The temperature would drop even further.

The wind would reach dangerous speeds.

Snow would fall so heavy that a person could not see 5 ft in front of them.

The storm would last for two days, maybe three, and this camp with its thin walls and broken windows would not protect anyone.

The commander called his officers together.

We have to evacuate, he said.

If we stay here, people will freeze to death.

When the women heard the news, the fear became terror.

Evacuation meant leaving the camp.

Leaving the camp meant going out into the blizzard.

Going out into the blizzard meant exactly what the propaganda had always promised.

They would be marched into the wilderness and left there.

The Canadians would save themselves and let the German prisoners freeze.

It made perfect sense.

Why would the enemy waste supplies and energy to save them? Why would soldiers risk their own lives for women who had worked for the Vermacht? The women looked at each other with wide, frightened eyes.

This was it.

This was the moment they had feared since the day they were captured.

They were going to die in the snow, and no one would ever know what happened to them.

The morning the blizzard was supposed to arrive.

The women woke up expecting the worst.

Through the thin walls, they could hear trucks pulling up outside.

Engines rumbled in the cold air.

Men shouted orders to each other.

The women pulled their thin coats tighter and stood together in small groups holding hands.

Some were crying quietly.

Others stared at nothing, their faces empty of hope.

Greta, who was 22 years old, looked at the youngest girl in the group.

She was only 19, barely more than a child.

“Stay close to me,” Greta whispered.

The girl nodded, her teeth chattering from cold and fear.

The doors opened and Canadian soldiers walked in.

The women braced themselves, but no one grabbed them.

No one yelled.

Instead, the officer in charge stood in the doorway and spoke in broken German.

We move now.

Storm coming.

Need to go to safe place.

The women did not move.

They did not believe him.

Safe Place was just another way of saying the middle of nowhere, where no one would find their frozen bodies until spring.

But they had no choice.

When soldiers tell you to move, you move.

They filed outside into the bitter cold.

The wind was already picking up, blowing snow across the ground in white sheets.

The women expected to see the soldiers pointing to a road, ready to make them march, but instead they saw something that made no sense.

The trucks were there, yes, but the soldiers were not loading the women into them.

One of the younger soldiers walked up to the officer and shook his head.

“Sir, the roads are completely blocked.

We have 60 cm of snow already and more coming.

The trucks cannot get through.” The officer nodded slowly, thinking.

Then he turned to his men and said something the women did not expect.

Then we carry them.

For a moment, nobody moved.

The German women stared at the Canadians.

The Canadians looked at each other.

Then slowly the soldiers started taking off their heavy winter coats.

They walked toward the prisoners, holding out the coats.

here,” one soldier said in English, gesturing for a woman to take his coat.

She looked at him like he was crazy.

He smiled a little and put the coat around her shoulders himself.

She was so shocked she could not speak.

All around, other soldiers were doing the same thing.

They gave away their scarves.

They gave away their gloves.

One soldier took off his wool blanket that he carried in his pack and wrapped it around a teenage girl whose fingers were black with frostbite.

“You need this more than me,” he said, even though she could not understand his words.

Then the caring began.

The weakest women, the ones who could barely stand, were lifted onto soldiers backs.

The men bent down and let the women climb on piggyback style, like fathers carrying tired children.

The women were terrified at first, stiff and afraid.

But the soldiers were gentle.

They adjusted the weight, made sure the women were secure, and then started walking into the snow.

The path ahead was not a road anymore.

It was just white emptiness with snow already up to their knees in some places.

The wind howled around them, blowing ice into their faces.

But the soldiers kept walking.

Greta walked beside a soldier who was carrying her friend Anna.

She watched his face as he trudged through the deep snow.

His breath came out in heavy clouds.

Sweat formed on his forehead, even in the freezing cold.

After 15 minutes, another soldier called out, “Switch time!” The man carrying Anna carefully lowered her down, and another soldier immediately took his place, lifting Anna onto his back without complaint.

They were rotating, Greta realized.

They were sharing the burden so no one man would collapse from exhaustion.

These soldiers were organizing themselves to save their prisoners lives.

Every hour, the group stopped to rest.

The soldiers pulled out thermoses from their packs and poured hot chocolate into small metal cups.

They passed the cups to the German women first.

Greta took a sip and almost cried.

It was sweet, so sweet and warm.

She had not tasted sugar in months.

In Germany, even before she was captured, sugar was impossible to find.

It was saved for the military and even then there was never enough.

But here these Canadian soldiers were giving their sugar rations to enemy prisoners.

Drink, the soldier said, pointing at the cup when Greta tried to give it back after one sip.

You need it more.

She drank it all, feeling the warmth spread through her chest.

The contrast was so sharp it hurt to think about.

Greta had expected bayonets pointed at their backs, forcing them to march until they dropped.

She had expected cruelty and mockery.

She had expected to be left in a ditch when she could not walk anymore.

But instead, she walked beside men who gave up their own warmth to keep her alive.

Men who carried her friends on their backs through waistdeep snow.

Men who shared their food and hot drinks.

men who stopped every 15 minutes to switch who was carrying the heaviest burden, making sure no one suffered alone.

The camp medic, a Canadian man with kind eyes and steady hands, moved through the group, checking on the women.

When he found one with an injured ankle, swollen and purple, he stopped everyone.

He opened his medical bag and pulled out a small glass bottle.

Morphine.

Greta knew what it was.

Morphine was precious, saved for the most serious injuries.

In the German army, they barely had any left.

But this medic used it on a German prisoner, injecting it carefully to ease her pain.

“This will help,” he said softly, though the woman could not understand him.

He wrapped the ankle tight and helped another soldier lift her onto his back.

As they walked, Greta’s mind was spinning.

Everything she had been taught was being challenged by what she saw with her own eyes.

The propaganda posters showed Allied soldiers as evil monsters.

The radio said they were barbarians without honor.

Her officers warned that capture meant torture and death.

But these men, these Canadian soldiers were suffering in the cold because they refused to leave prisoners behind.

They were exhausted, sweating despite the freezing temperature, their legs shaking from the effort of walking through the deep snow.

But they did not stop.

They did not complain.

When one woman stumbled, three soldiers rushed to help her up.

When another started crying from fear and cold, a soldier walking beside her started humming a song, something gentle and calming, trying to make her feel less afraid.

The storm was getting worse.

The wind screamed around them.

Snow fell so thick they could barely see 10 ft ahead.

But the line of soldiers and prisoners kept moving forward, step by difficult step.

And Greta, walking through that blizzard, surrounded by men she was supposed to fear, felt something breaking inside her chest.

It was not her body breaking.

It was something deeper.

It was the wall of lies she had lived behind her whole life, starting to crack and crumble in the face of simple, undeniable kindness.

They had been walking for almost 3 hours when Greta’s legs finally gave out.

One moment she was taking another step through the snow, and the next moment she was on her knees, her body simply refusing to go any further.

She had not eaten a real meal in weeks.

She had not slept well in months.

Her body had nothing left to give.

She knelt there in the snow, breathing hard, waiting for the soldiers to yell at her or leave her behind.

This was it, she thought.

This was where her luck ran out.

But a young Canadian corporal stopped beside her.

He looked down at her with concern, not anger.

He was maybe 24 or 25 years old with brown hair and tired eyes.

He bent down and said something in English that she did not understand.

Then he turned around and pointed at his back, making it clear what he wanted.

He was offering to carry her.

Greta shook her head quickly.

She did not want to be a burden.

She was the enemy.

She did not deserve this kind of help.

But the corporal just smiled a little and waited.

When she did not move, he gently helped her up and positioned her on his back, her arms around his shoulders, his hands holding her legs.

Then he started walking.

For the first few minutes, Greta was rigid with fear and shame.

She was an enemy soldier being carried by a man she was supposed to hate.

It felt wrong.

But as the corporal kept walking step after step through snow that was now up to his waist in places, she started to feel something else.

She felt his breathing heavy and labored.

She felt how his whole body worked to push through the deep snow while carrying her weight.

She felt him stumble once, catch himself, and keep going without complaint.

And slowly the fear started to change into something she could not name.

15 minutes passed, then 30, then an hour.

The corporal did not stop.

Other soldiers called out, “Hey, you need a break.” But he shook his head and kept walking.

His breath came harder now.

She could feel his shoulders shaking from the effort.

She could feel the heat from his body, even through their clothes.

After 2 hours, Greta could not stay silent anymore.

She had learned a little bit of English before the war in school, though she was never very good at it.

She leaned close to his ear and said quietly, “I am sorry, too heavy.

You tired?” The corporal turned his head slightly so she could hear him over the wind.

When he spoke, his voice was gentle, almost kind.

“My sister’s your age,” he said slowly, “So she might understand.

Someone would do this for her.” Then he kept walking.

Those words hit Greta like a physical blow.

She felt something inside her chest break open, something that had been locked tight her whole life.

This man was not carrying her because he had orders to do so.

He was not doing it to look good or to win points with his commander.

He was carrying her because he had a sister at home somewhere in Canada who was 22 years old just like Greta.

And in his mind, if his sister was trapped in a blizzard in a foreign country, he hoped that someone would carry her to safety, too.

He saw her as a person, not a German, not an enemy, not a piece of propaganda, just a young woman who needed help.

Greta pressed her face against his shoulder and cried.

She tried to be quiet about it, but her whole body shook.

Everything she had been taught, everything she had believed was a lie.

The propaganda posters that covered every wall in Germany showed Allied soldiers as monsters with evil faces ready to destroy German women.

The radio broadcast that played every day said the enemy had no honor, no mercy, no humanity.

Her teachers in school said the allies wanted to wipe Germany off the map and would torture anyone they captured.

Her own officers right before she was captured warned her that the Canadians would violate German women and leave them to die in ditches.

She had believed all of it because everyone around her believed it, too.

When an entire country tells you something is true, you stop questioning it.

But here, in the middle of a killing blizzard, with snow falling so thick she could barely see, a Canadian soldier was carrying her on his back because she reminded him of his sister.

He was exhausted.

His legs were shaking.

His breath came in gasps.

But he did not put her down.

He did not complain.

He just kept walking one step at a time, making sure she survived.

If this was a lie, Greta thought, what else was a lie? If they lied about the enemy being monsters, what else did they lie about? Did they lie about Germany winning the war? Did they lie about why the war started? Did they lie about who the real monsters were? The questions flooded her mind, and each one felt like another crack in a dam that was about to burst.

Her whole world view, everything she thought she knew about the world, was built on propaganda and fear.

And now she could see it for what it was.

She thought about the last two years of her life.

She thought about her friends who died in bombing raids.

She thought about the cities destroyed.

She thought about the millions of people suffering and dying.

And for what? So leaders could stay in power? So men in fancy uniforms could feel important.

She had given two years of her life to the Vermacht, sending their messages, helping their war machine run, believing she was protecting her country.

But her country had lied to her about everything.

They sent her to fight an enemy that was not evil.

They told her to fear people who were actually kind.

They filled her head with hate and then sent her out to suffer and die for their lies.

The corporal stumbled again, this time almost falling.

Another soldier rushed over.

Let me take her, mate.

You are done.

The corporal shook his head.

Almost there, he said.

I can make it.

The other soldier looked worried but nodded.

They kept walking.

Greta could see buildings in the distance now, barely visible through the snow.

The safe place was real.

It was not a trick.

They were actually taking the prisoners to shelter.

When they finally reached the new facility, a proper building with real walls and heat, the corporal carefully lowered Greta to the ground.

She stood on shaky legs and looked at him.

His face was red from effort and cold.

Sweat and melted snow dripped from his hair.

His hands shook from exhaustion, but he smiled at her, a real smile, and said, “You okay now?” Greta did not have the English words to say what she wanted to say.

She did not know how to tell him that he had just changed her entire life, so she just nodded and said the only English word she knew for certain.

“Thank you.

Thank you.” That night, lying on a real bed with a real blankets in a warm room, Greta stared at the ceiling and thought about everything.

The other women were talking quietly around her, still shocked by what had happened.

“They carried us,” one woman kept saying over and over like she could not believe it.

“They gave us their coats.

They gave us their food.

They carried us through a blizzard.” Another woman said, “Everything they told us was wrong.” And Greta whispered into the dark room.

“We marched, expecting death.

Instead, we found men who carried us to safety.

Everything we were told was a lie.” She thought about the corporal and his sister back in Canada.

She thought about all the soldiers who rotated carrying the weakest women, who shared their morphine and their hot chocolate, who gave up their warmth so prisoners would not freeze.

These were supposed to be the barbarians.

These were supposed to be the monsters without mercy.

But they had more mercy in their actions than her own government had shown in words.

The Nazi leaders who promised to protect Germany had sent young women into war zones with no real training and inadequate supplies.

But enemy soldiers, men who had every reason to hate Germans, had risked their lives in a blizzard to save them.

Greta rolled over and pulled the wool blanket closer.

It was the corporal’s blanket, the one he had insisted she keep.

She held it tight and made a promise to herself.

She would never forget this.

She would never forget what real humanity looked like.

And if she survived this war, if she made it home, she would tell everyone the truth about what happened in that blizzard.

She would tell them that the enemy was not who they thought.

And she would spend the rest of her life questioning everything she was told because she had learned the hardest way possible that governments lie and propaganda kills.

But kindness in the face of suffering is the only truth that really matters.

The war ended in May of 1945.

By the time Greta was finally allowed to go home, it was early 1946.

She had spent almost a year in Canadian custody, first in Belgium and then in a proper P camp in France.

The Canadians treated her well the whole time.

They gave her enough food that she gained back the weight she had lost.

They let her write letters home, though most of them never arrived because the German postal system had collapsed.

They even gave her a little bit of money when she was released, enough to buy a train ticket and some food for the journey.

Before she left, Greta asked one of the guards if he knew how to find the corporal who had carried her through the blizzard.

The guard checked some papers and wrote down an address in Ontario, Canada.

If you write to him, the letter should find him, the guard said.

Greta folded the paper carefully and put it in her pocket like it was made of gold.

She also carried two other things with her.

One was a small pressed flower, a tiny white wild flower she’d found growing near the facility where they had sheltered from the blizzard.

She had picked it in the spring and pressed it between two pieces of paper, saving it as a reminder that life could grow, even in places where people expected only death.

The other thing she carried was the wool blanket the corporal had given her.

It was worn and faded now with a few holes from mods, but she would not leave it behind.

That blanket meant more to her than almost anything else she owned.

It was proof that what happened was real, that it was not just a dream she had made up in her desperate mind.

The train ride back to Germany was long and depressing.

Everywhere Greta looked, she saw destruction.

Train stations were bombed into piles of broken concrete.

Bridges were blown apart, forcing the train to take long detours.

Fields that should have been growing food were torn up and poisoned.

Small towns were just empty shells, windows broken, walls collapsed, nobody living there anymore.

And the people on the train, the other Germans heading home, looked like ghosts.

They were thin and pale, and their eyes were empty.

Nobody talked much.

What was there to say? They had lost everything.

When Greta finally arrived in Hamburgg, the city she had grown up in, she almost did not recognize it.

Hamburgg had been one of the most beautiful cities in Germany before the war with grand buildings and busy streets and parks full of trees.

Now it looked like the surface of the moon.

Entire neighborhoods were just rubble and ash.

The bombing raids had destroyed almost everything.

People lived in the basement of destroyed buildings, making shelters out of whatever they could find.

Children with dirty faces and torn clothes begged for food on street corners.

Old women dug through piles of bricks looking for anything useful, anything they could sell or trade.

The smell of smoke and decay hung over everything.

This was what losing a war looked like.

This was what happened when leaders lied to their people and sent them to die for nothing.

Greta found her family living in what used to be a shop.

The front was completely destroyed, but the back room still had a roof and three walls.

Her mother cried when she saw her, holding her so tight, Greta could barely breathe.

Her father looked older than she remembered, his hair completely gray now, his face thin and lined with worry.

Her younger brother was there, too, missing his left arm from a battle in the final weeks of the war.

They were alive, which was more than many families could say, but they were broken.

That first night, sitting around a tiny fire made from broken furniture, Greta tried to tell them about the blizzard.

She told them how the Canadian soldiers had carried the prisoners to safety, how they had given up their own coats and food, how one man had carried her for two hours because she reminded him of his sister.

Her father listened with a hard face and then shook his head.

“They were trying to make us look weak,” he said.

“It was propaganda, a trick to make us grateful.” Her mother nodded, agreeing.

The Allies wanted to destroy Germany.

They still do.

“You were just lucky you did not see their real faces.” Greta stared at them in shock.

Even now, even after losing the war, even after their city was destroyed and their son lost an arm and they were living in a ruined shop, they still believed the lies.

They still clung to the propaganda like it was a life raft.

She tried again.

No, you do not understand.

They were kind.

They saved our lives when they could have left us to freeze.

They treated us like human beings.

But her father just got angry.

“Stop talking like that,” he said sharply.

“You sound like you’re on their side.

We were right to fight.

We were defending our homeland.

Do not dishonor your country by praising the enemy.

” Greta stopped talking after that.

She realized that some people would never let go of the lies, no matter what the truth was.

They needed to believe that Germany was right and everyone else was wrong.

Because if they admitted the truth, they would have to face what they had supported.

They would have to admit that they had cheered for a government that murdered millions and destroyed their own country.

It was easier to keep believing the lies than to face that kind of guilt.

But Greta could not live like that.

The contrast between what she had experienced and what she saw at home was too sharp, too painful.

In Canada, even enemy prisoners were treated with dignity and given enough food.

In Germany, German citizens were starving and living in ruins, abandoned by the same government that promised to protect them.

The Canadian soldiers had valued German lives more than Germany’s own leaders ever did.

That was the truth that burned in her chest every single day.

She kept the wool blanket for 40 years, folded carefully in a drawer.

Sometimes she would take it out and hold it, remembering that day in the blizzard.

She wrote letters to the corporal in Canada and eventually got a response.

He was doing well, working as a teacher, married with three children.

They exchanged letters for years, an unlikely friendship between former enemies.

He told her about Canada and she told him about trying to rebuild Germany.

She thanked him over and over for what he did and he always wrote back the same thing.

I did what anyone should do.

You were suffering and I could help.

That is all.

As Germany slowly rebuilt itself over the years, Greta made it her mission to tell young people about what really happened during the war.

She visited schools and spoke to students about propaganda and lies and how easy it is to hate people you have never met.

She told them about the blizzard and the Canadian soldiers who carried enemy prisoners through the snow.

We were taught to fear them, she would say, looking at the young faces in front of her.

We were told they were monsters who would hurt us.

But when we were freezing and broken, it was the enemy who carried us to warmth.

Humanity does not recognize uniform colors.

It only recognizes suffering and the choice to help.

When she was 62 years old, Greta donated the wool blanket to a war museum in Berlin.

She stood in front of a group of reporters and held up the faded worn blanket.

“This belonged to a Canadian soldier who gave it to me when I was a prisoner.

” She said, “He did not have to do that.

I was his enemy.” But he saw a young woman who was cold and suffering, and he chose kindness over hate.

This blanket is proof that even in the darkest moments of war, humanity can survive.

I kept it all these years to remind myself that propaganda dies the moment you look into the eyes of someone carrying you through a blizzard.

Greta lived to be 84 years old.

She spent decades telling her story, fighting against the lies that led to war, teaching people to question what their governments tell them.

In her final interview before she died, a young journalist asked her what the most important lesson was from her experience.

Greta thought for a moment and then said, “Real courage is not about fighting your enemies.

Real courage is about protecting them when they are vulnerable, even when everything in your culture tells you to hate them.

Those Canadian soldiers did not just save 87 women that day.

They proved that humanity can win even when everything else has failed.

They taught me that kindness is stronger than any propaganda.

And that lesson is what I want to leave behind.

The wool blanket still sits in that museum today, behind glass with a small sign that tells the story of the blizzard and the soldiers who carried their enemies to safety.

Thousands of people see it every year.

And maybe some of them looking at that old faded blanket learn the same lesson Greta learned.

That the real enemy is not the person on the other side wearing a different uniform.

The real enemy is the lie that tells you they are less human than you are.