They were told that American soldiers would burn them alive, torture them, do things too horrible to speak of.

For months, the propaganda had painted Americans as demons in human skin.

So, when Yuki heard the roar of flames and smelled smoke filling the munitions factory in Osaka, she knew exactly what was happening.

The Americans had finally come, and they had come with fire.

It was August 1945.

Japan was collapsing.

The factory where Yuki and 200 other young women worked had been bombed but not destroyed until now.

Through the smoke, she could hear screaming.

The metal doors had been locked from the outside.

The windows were barred.

The heat was rising.

This was it.

This was how they would die.

Burned alive by the enemy just as they had been warned.

But then came a sound she did not expect.

A crashing.

Metal bending, concrete cracking, men shouting in English.

And through the smoke and flames, American soldiers came smashing through the factory walls with sledgehammers and bare hands, pulling women out one by one, carrying them to safety.

Yuki did not understand.

The enemy was supposed to kill them.

Instead, they were saving them.

And that moment, that impossible moment, would break everything she thought she knew about the world.

If this story interests you, please hit the like button and subscribe for more true World War II stories that reveal the unexpected humanity that sometimes emerged even in the darkest moments of history.

The journey to this moment had begun 3 days earlier.

Yuki was 19 years old, though she looked younger.

Her hands were calloused from working with shell casings.

Her hair was cut short to keep it from catching in the machinery.

She had been working at the Osaka munitions factory since she was 16 along with hundreds of other young women.

They assembled artillery shells, packed gunpowder, tested firing mechanisms.

Dangerous work, necessary work, they were told for the emperor for Japan.

By August 1945, everyone knew Japan was losing the war.

The cities were ash.

Food was scarce.

American planes flew overhead daily.

And the air raid sirens had become as regular as breathing.

But still they worked.

What else could they do? The factory supervisors told them to keep going.

The military officers who visited said sacrifice was honor.

And the propaganda loudspeakers reminded them daily that the Americans were monsters who would show no mercy.

On August 14th, the bombing came, not from planes this time, but from artillery.

American forces had advanced closer than anyone realized.

The shells hit the facto’s east wing.

Fire broke out immediately.

The supervisors fled.

The military officers disappeared, and the women were told to gather in the main assembly hall and wait for evacuation orders.

Yuki huddled with the others in the vast concrete room.

The air smelled of smoke and machine oil.

Outside, they could hear explosions getting closer.

Some women prayed.

Others wept quietly.

A few sat in stunned silence.

Yuki clutched a small notebook she always carried.

The one where she wrote down her thoughts when the work got too hard.

She wanted to write something now, but her hands shook too much.

Then came the sound of the doors being locked.

Heavy metal sliding into place.

Chains rattling.

Someone had locked them inside.

Yuki stood and ran to the door, pulling at the handles.

They would not budge.

Other women joined her, shouting, pounding on the metal.

No one answered.

Through the barred windows high above, they could see smoke getting thicker.

The fire was spreading.

Panic swept through the room like a wave.

Women screamed.

Some collapsed.

Others tried to break the windows with tools, but the bars were too strong.

Yuki felt her chest tighten.

The smoke was seeping in through the ventilation shafts.

She could taste ash on her tongue.

This was not a mistake.

Someone had locked them in deliberately.

Someone had decided they were expendable.

Her mind raced through the possibilities.

Were the Japanese military afraid they would be captured and interrogated? Were they eliminating evidence? Or was this simply abandonment, leaving them to die rather than face the shame of surrender? Whatever the reason, the result was the same.

They were trapped in a burning building with no way out.

The heat grew intense.

Women pulled their workshirts over their faces to filter the smoke.

Yuki sank to the floor with a group of others, trying to stay below the worst of it.

Someone started singing a children’s song, soft and broken.

Others joined in, their voices thin and desperate.

It felt like a funeral hymn.

Then came the American voices, loud, urgent.

Yuki heard them before she saw anything.

English words she could not understand, shouted over the roar of flames.

The women fell silent, listening.

What was happening? Were the Americans here to finish what the fire had started? The wall exploded inward, not from bombs, but from force, sledgehammers smashing through concrete, boots kicking at weakened sections, and then they appeared through the smoke and dust.

American soldiers, tall, covered in soot, sweating from exertion.

They did not raise weapons.

They raised their hands, gesturing frantically.

One of them shouted something that sounded like commands, but his face showed urgency, not cruelty.

The women did not move.

They stared in frozen terror.

These were the demons from the propaganda.

The monsters who had burned their cities, and now they were here.

But instead of attacking, the soldiers were reaching toward them, pulling them up, pushing them toward the hole in the wall.

One soldier grabbed Yuki by the arm and she flinched, expecting pain.

Instead, he pulled her gently but firmly towards safety.

His grip strong but not brutal.

Outside, the air was clearer.

Yuki stumbled into daylight, coughing violently.

All around her, American soldiers were dragging women out of the building, carrying those who could not walk, shouting at each other to hurry.

The seeing factory was fully engulfed now, flames shooting from every window.

If the soldiers had arrived even 5 minutes later, everyone inside would have died.

Yuki collapsed onto the ground, gasping for clean air.

Her throat burned.

Her eyes streamed with tears from the smoke.

But she was alive.

They were all alive.

And the Americans, who were supposed to be monsters, had just risked their lives to save them.

The immediate aftermath was chaos.

Women lay scattered across the factory yard, coughing, crying, some still in shock.

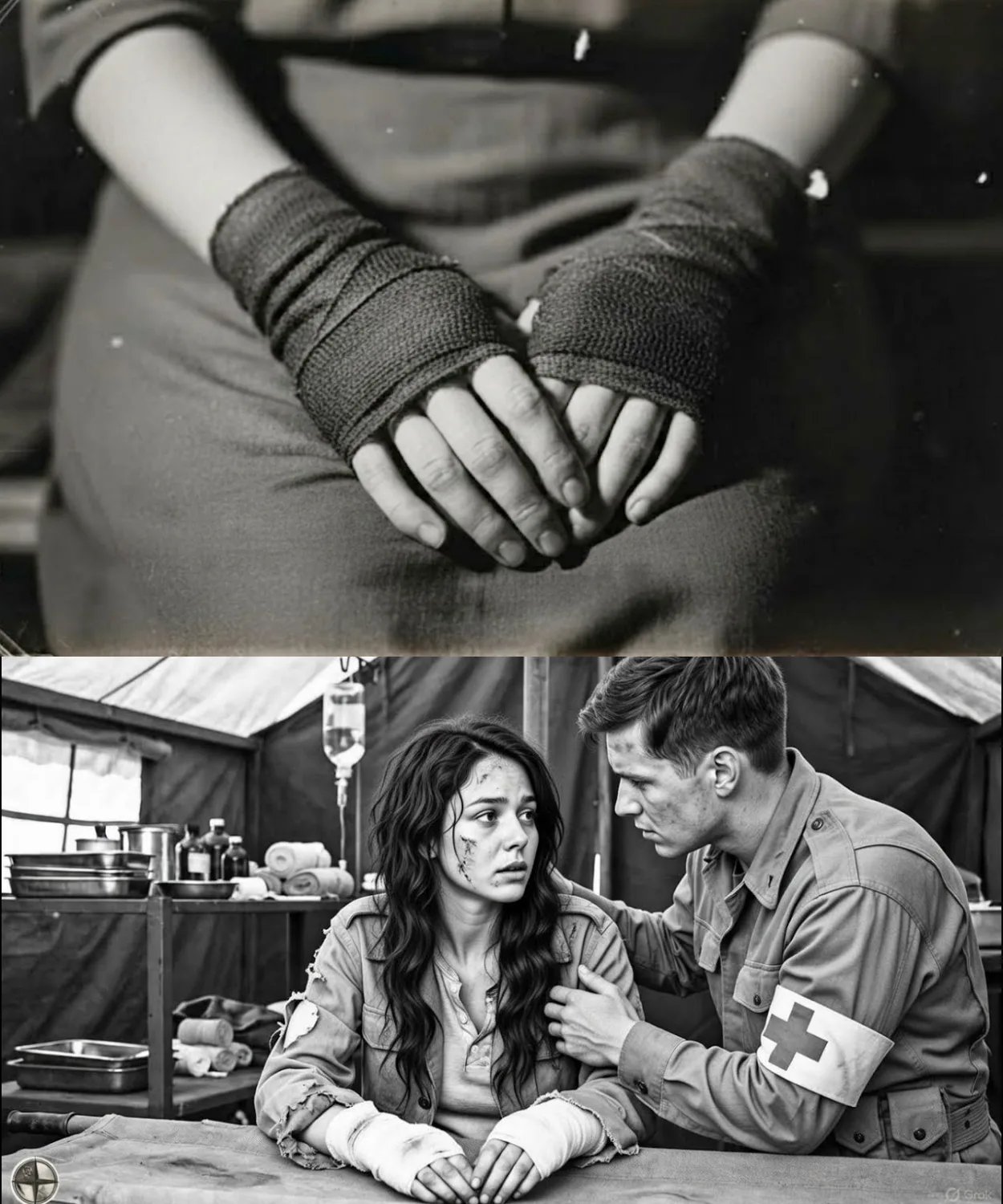

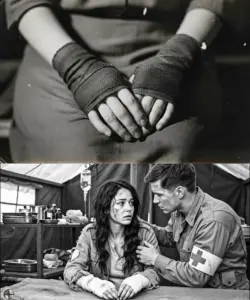

American medics appeared almost instantly, carrying medical bags and water cantens.

They moved from woman to woman, checking for injuries, offering water, wrapping burns in clean white bandages that looked impossibly fresh and new.

Yuki watched in disbelief as a young American medic knelt beside her.

He could not have been older than 22.

His face was smudged with ash, but his eyes were kind.

He said something in English, slow and gentle, then held up a canteen.

Water.

He was offering her water.

Yuki hesitated, then took it with shaking hands.

The water was clean and cool.

She had not tasted water this clean in months.

The medic gestured to her throat, asking something she could not understand.

He seemed to be asking if she was hurt.

Yuki shook her head though her throat felt like sandpaper and her lungs achd.

The medic smiled, patted her shoulder gently and moved to the next woman.

That simple touch, that moment of human concern shattered something inside Yuki.

These were supposed to be the enemy.

But this young man treated her like she mattered.

Around her, similar scenes were unfolding.

An older woman with severe burns on her arms was being carefully tended to by two medics who worked with practiced efficiency.

They applied some kind of ointment that made her gasp in relief.

A girl who looked barely 15 was wrapped in a blanket despite the summer heat, trembling from shock.

An American soldier sat beside her, speaking softly in English.

His tone obviously meant to comfort even if she could not understand the words.

Trucks arrived within the hour.

military trucks with American markings.

The soldiers helped the women climb aboard, lifting those too weak to manage on their own.

Yuki found herself sitting in the back of a canvas covered truck with about 20 other women.

All of them silent.

All of them processing what had just happened.

The propaganda had been so clear, so certain.

Americans were cruel.

Americans were savage.

Americans would show no mercy to Japanese people, especially women who had worked in weapons factories.

But that was not what happened.

Not even close.

The soldiers had saved them.

More than that, they had risked their own lives to do it.

The factory had been fully engulfed when they smashed through those walls.

They could have waited for it to burn out.

They could have left the women to die, and no one would have blamed them.

Instead, they came through fire and smoke to pull out people who had spent years making weapons to kill Americans.

The truck rumbled through destroyed streets.

Osaka was a wasteland.

Buildings reduced to skeletal frames.

Entire neighborhoods flattened.

The women stared out at the ruins of their city, seeing the full extent of the destruction for the first time.

The factory had been isolated, and they had been too busy working to see much beyond its walls.

Now, confronted with the reality of what the war had done, several women began to cry quietly.

They arrived at a large building that had once been a school.

American flags hung outside.

Soldiers were everywhere, but they moved with purpose, not aggression.

The women were led inside to a large gymnasium that had been converted into a processing center.

Tables were set up.

More medics waited and at the far end, steam rose from what looked like makeshift shower stations.

A Japanese American translator appeared, a woman in her 30s wearing an American military uniform.

She spoke to the group in clear Japanese, explaining what would happen next.

They would be examined by doctors.

They would be given clean clothes.

They would be allowed to wash.

They would be fed.

Then they would be transported to a temporary holding facility until their status could be determined.

The word holding facility sent a ripple of fear through the group.

That sounded like a prison.

The translator must have seen their faces because she added quickly that it was not a punishment.

It was for their safety and for processing.

Japan had surrendered, she explained.

The war was over.

They were no longer combatants, but they needed to be accounted for and cared for until proper arrangements could be made.

The war was over.

The words seemed impossible.

Yuki had known it was coming, but hearing it confirmed.

Hearing it from an American officer, made it real in a way nothing else had.

Japan had lost.

The emperor had surrendered.

Everything they had worked for, everything they had been told to believe had ended in defeat.

The medical examinations were thorough but respectful.

Female medics handled most of it, checking for injuries, burns, signs of smoke inhalation.

Yuki waited her turn, watching as each woman was treated with a level of care that felt surreal.

When it was finally her turn, the medic who examined her was an older woman with gray hair and gentle hands.

She checked Yuki’s throat, listened to her breathing, examined her smoke irritated eyes.

Then she gave her a small white pill and a cup of water, explaining through the translator that it would help with the coughing.

But it was the showers that truly broke through their defenses.

The women were led in small groups to the shower area.

Yuki had not bathed properly in weeks.

The factory had only cold water taps and basic facilities, but these showers had hot water.

Real hot water.

And they were given soap.

Actual bars of soap, white and clean, smelling faintly of something floral.

Yuki stood under the hot water and felt months of grime, sweat, and smoke wash away.

The soap lthered thick and rich.

She scrubbed her skin until it turned pink.

She washed her hair three times.

unable to believe that the water stayed hot, that the soap did not run out, that no one was rushing her or telling her to hurry.

Around her, other women were having the same experience.

Some were crying, others were laughing in disbelief.

The sound echoed off the tile walls, a strange mix of relief and confusion.

When Yuki stepped out, she was handed a towel, a real towel, thick and soft and clean, and then clothes.

Not prison uniforms, not rags, but simple cotton dresses, clean and whole, without patches or stains.

They were Americanmade, clearly, but they fit well enough and they were new.

Yuki put on the dress and felt like a different person.

For the first time in years, she felt clean.

Truly clean.

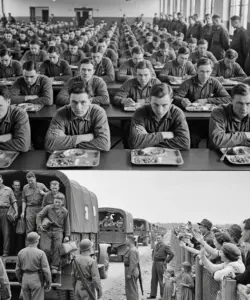

The next shock came in the form of food.

The women were led to another large room where tables had been set with trays.

Metal trays divided into sections.

Each section filled with food.

Real food.

Rice, yes, but also vegetables that were fresh, not wilted.

Some kind of meat in a brown sauce.

Bread that was soft and white.

And fruit.

Actual fruit.

Yuki picked up an apple and just stared at it.

She had not seen an apple in over a year.

The women ate in silence at first.

Too hungry and too shocked to speak.

Yuki bit into the apple and the sweetness exploded in her mouth.

Tears sprang to her eyes.

It was just an apple, just fruit.

But after months of watery soup and moldy rice, it tasted like a miracle.

Around her, similar reactions were happening.

Some women ate slowly, savoring every bite.

Others ate quickly, as if afraid the food might disappear.

An American soldier stood near the door, watching them eat.

He was young, maybe 25, with kind eyes and a slight smile.

He caught Yuki’s eye and gave her a small nod, as if to say, “It is okay.

Eat.

You are safe.

” That simple gesture, that small acknowledgement of her humanity, made Yuki’s chest tighten.

Who were these people? How could they be the monsters from the propaganda when they acted like this? That night, the women were given sleeping quarters in a converted warehouse.

Cotss were set up in rows, each with a pillow and two blankets.

The room was lit by electric lights.

It was warm.

It was dry.

It was clean.

Yuki lay down on her cot and stared at the ceiling, her mind spinning.

24 hours ago, she had been locked in a burning factory, certain she was about to die.

Now she was clean, fed, and lying on a real bed with clean blankets.

She pulled out her small notebook, which she had somehow managed to keep through everything.

The pages were smoke stained and crumpled, but it still worked.

By the dim light, she wrote, “They saved us.

The Americans saved us.

I do not understand.

Everything we were told was wrong.

They broke through walls to pull us from fire.

They gave us water, food, clean clothes.

They treated our injuries.

Why? Why would the enemy do this? Around her, women whispered to each other in the darkness.

Some were expressing the same confusion.

Others tried to rationalize it, suggesting it was a trick or a temporary kindness before the real cruelty began.

But Yuki did not think so.

She had seen the medic’s eyes when he offered her water.

She had felt the gentleness of the soldier who pulled her from the factory.

That had not been an act.

That had been real.

The days that followed established a routine that none of the women could have imagined.

They were transported to a larger facility outside Osaka, a former Japanese military base that had been converted into a civilian processing center.

The American military had moved quickly to establish order.

And the facility reflected that efficiency.

The women were housed in long barracks buildings that had been cleaned and repaired.

Each woman had her own bunk with clean sheets that were changed weekly.

There were communal bathrooms with working toilets and showers that had hot water most of the time.

The compound had a messaul, a medical clinic, a small library, and even a courtyard where women could sit outside in the sun.

The routine was simple.

Wake at 7 to a bell, not a siren.

Breakfast in the mess hall at .

Work assignments from 9 to 3.

Dinner at 5.

Free time until lights out at 9.

The work was not hard.

They sorted supplies, helped with laundry, assisted in the kitchens, or worked in the small garden that had been started.

Nothing like the dangerous factory work they had done before.

And they were paid.

Not much, but actual money.

American military script that could be used in the small canteen that sold toiletries, candy, and other small items.

The food continued to be the biggest shock.

Three meals a day, every day, with portions that seemed impossibly large.

Rice with every meal, yes, but also vegetables, meat, bread, and sometimes desserts.

Real desserts made with sugar and butter.

Yuki had forgotten what cake tasted like the first time they served chocolate pudding.

She almost could not bring herself to eat it.

It seemed too precious, too impossible.

But the most confusing part was how the Americans treated them.

The guards were present, yes, and the compound was fenced, but the atmosphere was not like a prison.

The soldiers were polite.

They said good morning.

They held doors open.

They helped carry heavy things.

When one woman sprained her ankle, an American soldier carried her to the medical clinic on his back without hesitation.

Yuki found herself assigned to work in the library, a small room that had been stocked with Japanese books collected from various sources.

Her job was to organize them and help other women find reading material.

It was peaceful work, quiet work, and it gave her time to think.

too much time perhaps because the more she thought the less sense anything made.

Letters began to arrive from the outside world.

The Red Cross had set up a system for families to send messages.

Yuki received one from her mother after 3 weeks.

The paper was thin and the writing shaky, but the words were clear.

Her mother was alive.

Her younger sister was alive.

They were living in a refugee camp in the countryside, surviving on rations and charity.

Her mother wrote that she was grateful Yuki was safe.

But the tone carried something else, too.

Confusion, maybe even a hint of shame, that Yuki was being held by Americans while the family suffered in Japanese camps.

That letter stayed with Yuki for days.

Her family was barely surviving on scraps while she ate three full meals a day.

Her mother and sister lived in a crowded refugee camp while she had her own bunk with clean sheets.

The war had ended, but the suffering had not.

For millions of Japanese people, the suffering was getting worse.

Cities were destroyed.

Food was scarce.

The infrastructure had collapsed.

And yet, here in an American facility, she was cleaner, healthier, and better fed than she had been in years.

The contradiction gnawed at her.

In the evenings, women would gather in small groups to talk.

Some tried to maintain that the Americans were still the enemy, that this treatment was temporary or strategic.

Others admitted openly that they had been lied to.

The debates could get heated, especially among the older women who had more invested in the wartime ideology.

Yuki mostly listened.

One evening, a woman named Ko, who was in her late 20s and had worked as a supervisor at the factory, spoke up.

Her voice was bitter.

She said that the government had abandoned them, locked them in that factory to die rather than let them fall into enemy hands.

But the enemy had saved them.

The enemy fed them.

The enemy gave them medicine when they were sick.

What did that say about their own government? The question hung in the air.

No one had a good answer.

To admit that your own government had failed you, had betrayed you, was to admit that everything you had endured, all the sacrifices had been for nothing.

It was easier to believe the Americans had ulterior motives.

But the evidence of kindness kept piling up, making it harder and harder to maintain that belief.

The medical clinic became another source of transformation.

Yuki developed a persistent cough from the smoke inhalation.

The American doctors gave her medicine, real medicine, not the herbal remedies or placeos that had been available during the war.

Within a week, the cough was gone.

Other women with more serious conditions were treated with the same care.

A woman with an infected wound received antibiotics and surgery.

A girl with chronic malnutrition was put on a special diet and monitored daily until her health improved.

The American nurses and doctors treated them like patients, not prisoners.

They explained treatments through translators.

They asked permission before procedures.

They showed concern when someone was in pain.

One doctor, an older man with gray hair and gentle hands, spent extra time with an elderly woman who was terrified of needles calming her down before giving her a vaccination.

That simple act of patience, that recognition of her fear and dignity, moved several women to tears.

Physical changes began to show.

After a month of regular meals and medical care, the women looked different.

Faces filled out, eyes brightened, hair regained its shine, skin cleared up.

Yuki caught her reflection in a window one day and barely recognized herself.

She looked healthy, more than healthy.

She looked alive in a way she had not in years.

But this physical transformation brought its own guilt.

How could she look this healthy when her family was starving? How could she gain weight when people across Japan were dying of malnutrition? The contradiction created a constant low-level anxiety that never quite went away.

The Americans also provided small luxuries that felt almost cruel in their kindness.

The canteen sold candy bars.

American chocolate that was rich and sweet.

It sold soap and shampoo that smelled nice.

It sold writing paper and pencils.

Yuki bought a new notebook with her work script and continued writing her thoughts documenting this strange reality she found herself in.

She wrote, “Today they showed us a movie in the recreation hall, an American film with Japanese subtitles.

It was about a family and their farm and their struggles.

It made the Americans look human, ordinary, not so different from us.

I do not know what to think anymore.

Everything is upside down.

Human moments continued to accumulate.

A guard named Thompson learned basic Japanese phrases and would greet the women each morning with a cheerful Ohio Goasu that was badly pronounced, but clearly well-intentioned.

He had pictures of his own family back in Nebraska, and he would show them to anyone interested, pointing out his wife and two daughters with obvious pride and love.

Another soldier, a young man barely out of his teens, taught some of the women basic English phrases.

He was patient and kind, laughing goodnaturedly when they mispronounced words.

He seemed genuinely happy to help.

Yuki learned to say, “Thank you,” and “Good morning,” and “How are you?” in English.

The words felt strange in her mouth.

But the soldiers encouragement made her want to try.

These interactions, these small human connections were perhaps more devastating than any cruelty could have been.

It would have been easier if the Americans had been monsters.

Hatred is simple.

It requires no reflection, no questioning.

But kindness demands a response.

It demands that you see the other person as human.

And if they are human, if your enemies are just people like you, then what does that make the war? What does it make the suffering? The transformation did not happen all at once.

It was gradual, like ice melting slowly under spring sun.

For Yuki, it began with small questions that grew into larger doubts and eventually into a complete re-evaluation of everything she thought she knew.

The first crack came from a conversation with Ko, the former factory supervisor.

They were sitting in the courtyard one afternoon enjoying the autumn sun.

Ko had been quiet for days processing something.

Finally, she spoke.

She said that she had been a true believer.

She had believed in the emperor, in the greater East Asia co-rossperity sphere, in Japanese superiority, in the righteousness of the war.

But now she could not stop thinking about one fact.

The Japanese military had locked them in a burning building and left them to die.

The American military had smashed through walls to save them.

That fact, that simple truth had shattered her entire world view.

If Japan valued its own people so little, and America valued even enemy lives enough to risk their soldiers safety, then who were the real barbarians? Yuki had no answer.

She had been thinking the same thing, but had not dared to say it out loud.

To speak it was to make it real.

To make it real was to admit that they had been lied to, that their sacrifices had been for leaders who saw them as expendable.

That the war they had supported had been built on lies.

The evidence kept mounting.

The American doctors treated everyone equally, regardless of their role in the war.

A woman who had been a factory supervisor got the same care as a woman who had just worked on the assembly line.

There was no hierarchy of suffering.

No calculation of who deserved help.

Everyone mattered.

Everyone was treated with basic human dignity.

This concept was foreign to many of the women.

Japanese society was built on hierarchy, on knowing your place, on accepting that some people mattered more than others.

But the Americans seemed to operate on a different principle.

They acted as if every person had inherent worth regardless of their station or their past.

Yuki wrote in her notebook, “They treat us like we are human beings who deserve basic care.

Not because of who we are or what we did, but simply because we are human.

I have never been treated this way before.

Not by the factory bosses, not by the military officers.

Not even by our own government.

What kind of world do the Americans live in where this is normal? The answer came gradually through various sources.

The Japanese American translator, Mrs.

Tanaka, sometimes gave informal talks about American society.

She explained concepts like individual rights, democracy, equality before the law.

These ideas sounded radical, almost dangerous, but they also explained a lot about why the Americans acted the way they did.

If you believed that all people had basic rights simply by being human, then of course you would save people from a burning building, even if they were technically enemies.

If you believed in the rule of law and fair treatment, then of course you would feed prisoners and give them medical care.

It was not kindness exactly.

It was principle.

It was a different way of seeing the world.

This realization was both liberating and terrifying.

Liberating because it suggested that human dignity was not something granted by emperors or governments, but something inherent that could not be taken away.

Terrifying because it meant questioning everything about how Japanese society was organized, about loyalty and duty and the meaning of honor.

The debates in the barracks grew more intense.

Some women clung to the old beliefs.

They argued that American kindness was manipulation, a form of psychological warfare designed to break their spirits.

They insisted that Japan had been right to fight, that the cause had been just, even if the execution had been flawed.

They saw accepting American charity as a betrayal of everything they had endured.

Others, like Yuki and Ko, had moved past that.

They could not unsee what they had seen.

They could not unfeill the kindness they had experienced.

To deny it would be to deny reality itself.

But accepting it meant living with a painful truth.

They had suffered for nothing.

Their friends had died for nothing.

The war had been a waste of human life on a scale almost impossible to comprehend.

One night, Yuki had a conversation with a younger woman named Hana, who was only 17.

Hana had been raised on propaganda, had never known anything else.

She asked Yuki a simple question.

If the Americans were really evil, why did they save us? Why do they feed us? Why do they care if we are sick? Yuki answered honestly.

She said she did not know, but she said that maybe, just maybe.

The propaganda had been wrong.

Maybe the Americans were not evil.

Maybe they were just people.

Maybe their government and system had problems.

like any government and system.

But maybe the core belief in human dignity and basic rights made them act differently than the Japanese military had.

Hana cried that night, not from sadness, but from the pain of having your entire world view collapse.

Yuki held her and let her cry.

She understood.

She had done her own crying in private, mourning the loss of certainty, the loss of simple answers.

The most dangerous realization came when Yuki understood that the Americans greatest weapon was not their bombs or their industry or their military might.

It was their values.

By treating even their enemies with basic human dignity, they demonstrated a moral superiority that was impossible to deny.

Cruelty could be met with cruelty.

Violence could be met with violence.

But how do you fight kindness? How do you hate people who risk their lives to save you? Yuki wrote, “Hatred is easy.

It builds walls and keeps you safe behind them.

But kindness slips through every crack.

It demands you acknowledge the humanity of the other.

And once you do that, once you see them as human, hatred becomes impossible.

The Americans have not broken us with cruelty.

They have broken us with compassion.

And I do not know if I am grateful or angry or both.” The transformation was not universal.

Some women never changed.

They held on to their beliefs with desperate intensity, seeing any softening as weakness or betrayal.

But many others, perhaps the majority, found themselves in the same place as Yuki.

Confused, grateful, guilty, changed.

The turning point came on a cold November morning.

A representative from the American military government arrived to speak to all the women.

They gathered in the messaul, curious and nervous.

The representative was a colonel, an older man with a serious face and kind eyes.

He spoke through Mrs.

Tanaka, the translator.

He told them that arrangements were being made for their release.

They would be allowed to return to their families.

The American occupation government was setting up systems to help displaced persons reunite with relatives, find housing, and access food distribution centers.

They were not prisoners.

They were survivors and they deserved the chance to rebuild their lives.

But then he said something that stunned everyone.

He said that before they left, he wanted them to understand something.

He wanted them to know that the American soldiers who saved them from that factory did so not because of orders, but because it was the right thing to do.

Some of those soldiers had lost friends and brothers to Japanese forces.

They had every reason to hate, but they chose to save lives instead.

because that is what humanity requires.

That is what honor demands.

The room was silent.

The colonel continued.

He said that war makes people forget that the enemy is human.

It makes cruelty easier.

But the best of humanity emerges when people choose compassion even when they have every excuse not to.

He said he hoped the women would remember this.

He hoped they would tell their families, their children, their grandchildren.

not as propaganda for America, but as a reminder that even in the darkest times, people can choose to be better than their hatred.

When he finished, the colonel did something unexpected.

He bowed, a deep, respectful bow to the entire room.

An American military officer bowing to Japanese women who had made weapons to kill his countrymen.

The gesture broke something in the room.

Women began to cry openly.

Some returned the bow.

Others just sat in stunned silence.

Yuki felt tears streaming down her face.

She understood now.

This was not about politics or strategy or winning hearts and minds.

This was about a fundamental belief that every human life had value.

That even enemies deserved basic dignity.

That mercy was not weakness but strength.

That evening, Yuki sat alone in the library and wrote the longest entry in her notebook.

She wrote about the burning factory and the soldiers smashing through walls.

She wrote about the hot water and the soap and the clean blankets.

She wrote about the food and the medicine and the small kindnesses that had accumulated day after day.

She wrote about her confusion and her guilt and her gradual understanding.

And she wrote this, “I thought I would die hating the enemy.

Instead, the enemy taught me what it means to be human.

They showed me that dignity is not given by governments or emperors.

It is something we owe to each other simply because we are all human.

The Japanese military locked us in a burning building.

American soldiers smashed through walls to save us.

I will never forget that.

I will tell my children and they will tell theirs.

Not to praise America or condemn Japan, but to remember that we always have a choice.

We can choose cruelty or compassion.

fear or hope, hatred or humanity.

She closed the notebook and looked at her reflection in the darkened window.

The thin, exhausted factory worker was gone.

In her place was a young woman with clear skin, bright eyes, and a future.

The physical transformation was obvious, but the internal transformation was more profound.

She was not the same person who had been pulled from that factory.

She never would be again.

The release process began in December.

Women were called in small groups, given travel documents and small amounts of money, and transported to collection points where they could begin the journey home.

Yuki’s turn came on a gray winter morning.

She packed her few belongings, including her notebook, and joined the others waiting by the gate.

Guard Thompson was there to see them off.

He shook hands with each woman, his Japanese goodbye still badly pronounced, but sincere.

When he got to Yuki, he pressed something into her hand, a chocolate bar.

He smiled and said in broken Japanese that it was for the journey.

Yuki bowed deeply, unable to speak past the lump in her throat.

The journey back to her village took three days.

She traveled by train and bus through a country she barely recognized.

The devastation was total.

Cities were rubble.

Bridges were destroyed.

People looked hollow and desperate.

The contrast between the American facility and the reality of Japan was almost unbearable.

When she finally arrived at the refugee camp where her family was staying, her mother almost did not recognize her.

Yuki looked too healthy, too strong.

Her mother was thin as paper, her sister not much better.

The reunion was joyful, but complicated by the obvious disparity.

Yuki tried to explain what had happened, but the words sounded wrong.

How could she tell her starving family that the Americans had fed her three meals a day? She shared the chocolate bar Thompson had given her.

Her sister had forgotten what chocolate tasted like.

They made it last for days, taking tiny bites, savoring something that had once been ordinary, but was now precious beyond measure.

In the months and years that followed, Yuki did what she had promised herself she would do.

She told the story.

She told it to her family, to her neighbors, to anyone who would listen.

Some did not believe her.

Some accused her of being brainwashed or of becoming a traitor.

But others listened and understood.

She married eventually to a man who had survived the war in Burma.

She told him the story on their third date.

He listened quietly, then told her his own story of being captured by British forces and treated with unexpected dignity.

They understood each other in a way that others could not.

They had children, three daughters, and Yuki told them the story of the burning factory and the American soldiers who smashed through walls.

She showed them her smoke stained notebook, now a treasured family heirloom.

She explained that war was terrible and hatred was easy, but that the most important choice any person could make was to see the humanity in others, even in enemies.

And so the soap and hot water, the clean blankets, the chocolate bars, and most of all, the smashed walls became more than just memories of captivity.

They became symbols of a truth that transcends nations and wars.

That even in humanity’s darkest moments, individuals can choose compassion over cruelty, mercy over vengeance, life over death.

For Yuki and the women who survived that burning factory, the taste of that first apple, the feel of hot water, the sound of concrete cracking as soldiers broke through to save them became reminders that the enemy’s greatest weapon was not fire or steel.

It was the simple recognition that every human life has value.

Years later, when Yuki was an old woman, her granddaughter asked her why she kept the smoke stained notebook so carefully.

Yuki opened it to the page where she had written about the soldiers breaking through walls.

She read the words aloud, her voice still strong.

They showed me that dignity is not given by governments or emperors.

It is something we owe to each other simply because we are all human.

She closed the notebook and looked at her granddaughter.

She said, “Remember this.

In a world that tells you to hate, choose to see humanity because kindness is harder than hatred and mercy requires more courage than cruelty.

But it is the only thing that can break the cycle of suffering.

That is the story worth remembering.

Not because it makes America look good or Japan look bad, but because it reminds us that we always have a choice.

We can lock people in burning buildings or we can smash through walls to save them.

We can see others as enemies to be destroyed or as humans who deserve basic dignity.

The choice is ours always.

If this story moved you, please hit the like button and subscribe to this channel for more true accounts of World War II history that reveal the complexity of human nature even in the darkest times.

These stories, though painful, need to be told and remembered.