August 1945, the Pacific War had ended with a sudden silence broken only by the thunderous echo of two bombs whose shadows still lingered in Nagasaki and Hiroshima.

Across Japan, surrender was a word spoken in whispers heavy with humiliation, disbelief, and grief.

For those in uniform, women who had served in hospitals, communication units, and auxiliary corps, captivity followed swiftly.

On August 20th, 1945, a group of Japanese female prisoners numbering just under 300 were transported from Guam to the American mainland.

Among them was Yumiko Aai, a 24year-old nurse from Nagasaki who had survived the final weeks of the Pacific campaign.

With her units scattered and leaderless, she carried little more than a notebook and a pair of gloves worn thin by years of rationing.

The ship’s deck smelled of oil, salt, and unfamiliar tobacco.

American guards, most of them barely older than the prisoners, walked with a kind of casual confidence that seemed alien to Yumiko.

Their uniforms were clean, their boots polished, and their bodies broad and tall in ways she had never seen in Japan.

She remembered her instructor’s warning that American men were weak, lazy creatures softened by capitalist indulgence.

Yet the man who offered her water that morning, his suntan arm steady as iron, was anything but weak.

Beside her, Kiko Sato, a wiry 20-year-old radio operator from Okinawa, whispered in disbelief.

They looked impossible.

Were we lied to all this time? The voyage to California took 10 days.

During those days, the women experienced the first cracks in the propaganda that had shaped their world view.

Meals were abundant by their standards.

Cans of fruit, white bread, real coffee.

Some prisoners ate timidly, suspecting a trek.

Others wept silently at the sight of sugar, butter, and meat portions larger than anything they had known in years.

When the transport finally docked in San Francisco, the city rose before them in a misty morning haze.

skyscrapers of steel and glass, bridges arching across the bay, and the endless bustle of trucks and automobiles.

For many, it was the first time they had seen a western city outside of distorted photographs used in wartime lessons.

To Ko, it looked like the future itself.

They were taken inland by train, the rhythmic clatter of wheels echoing against landscapes vast beyond imagination.

rolling fields of wheat, orchards heavy with fruit, herds of cattle grazing in abundance.

It was a panorama that mocked everything they had been taught about starving, crumbling America.

Hi Nishida, a 19-year-old medical student conscripted in the last months of the war, scribbled in her journal, “If this is the land of a dying race, then the world must be upside down.

Even the children at the stations look stronger than our soldiers.

Their destination was Camp McCoy in Wisconsin, one of several facilities prepared to hold female prisoners of war.

It was here that their confrontation with truth and with themselves would begin.

The camp itself defied every expectation.

Rows of wooden barracks stood clean and orderly.

Kitchens smelled of bread and soup.

Showers offered hot water on demand, a luxury unknown even in most Japanese cities during the war.

Guards spoke not with cruelty, but with brisk efficiency, sometimes even politeness.

When one of the women asked how long they could remain under the hot spray of the showers, the American matron in charge blinked in confusion.

“Until you’re clean, honey,” she said.

The first days passed in a blur of medical examinations.

uniform distribution and orientation.

Doctors recorded weights and heights, their pencils scratching out figures that seemed unreal to the Japanese women.

Average American women stood taller, weighed more, and bore stronger teeth and bones.

Margaret Collins, a Red Cross nurse assigned to assist, later wrote in her diary, “They look at our charts as though we are tricking them.

Some cried when told they were malnourished by our standards.

One asked if we had confused kilograms with pounds.

The disbelief is profound.

It is as if their world has cracked open.

In the evenings, as Cicada sang outside the barracks, Yumiko, Ko, and Hioko whispered about the faces of the American guards, about the way the cook tossed away leftover breadcrusts, about the endless supplies of soap and fabric.

Every discarded cigarette, every casually repaired truck, every confident stride of the men in uniform struck them with the same thought.

Everything they had been taught was a lie.

Yet disbelief was not the same as acceptance.

Some prisoners clung to explanations that the guards were specially selected giants, that the food was staged, that the waste was deliberate propaganda.

But in the silence of the Wisconsin Knights, as trains rumbled in the distance, and the smell of pine drifted into the camp, the question grew heavier in each woman’s heart.

If our leaders lied to us about this, what else had they lied about? The story of their captivity had only just begun.

September 1945, Camp McCoy settled into its routines, revy sounded at dawn.

Mesh halls filled with the clatter of trays and the hum of English the prisoners struggled to understand.

And by evening the barracks grew quiet under the watch of the tall flood lights.

To outsiders it was order.

To the Japanese women inside it was a waking dream that eroded certainty one grain at a time.

Yumiko Arai worked in the infirmary under the supervision of American medics.

Each day she wrapped wounds and treated infections with supplies that seemed inexhaustible.

Gauze, antiseptic, penicellin.

Back home, she had learned to boil needles until they dulled and to ration bandages like gold.

Here, Margaret Collins, the Red Cross nurse, opened fresh packages without hesitation and discarded half-used bottles of alcohol.

Yumiko could not stop herself from whispering wasteful, wasteful, as if speaking the word might anchor her to the world she had left behind.

Kosato was assigned to kitchen duty where she first encountered the scale of American abundance.

The storoom smelled of flour, coffee, and canned fruit stacked in endless rows.

She watched cooks crack eggs into giant bowls, whisking dozens at a time, then casually pour leftovers into the trash.

At first, she assumed this was theater, an illusion staged for the prisoner’s benefit.

But day after day, the waste was real.

One evening after disposing of an untouched loaf of bread, she broke down in tears, remembering her younger brother in Okinawa gnawing on sweet potato skins to silence his hunger.

Hioko Nishida, curious and sharpeyed, began writing everything down in her little notebook.

The height of the guards, the daily rations, the number of trucks that entered the compound.

She measured and compared, desperate to find a logical explanation.

Her training as a medical student demanded proof.

And yet every statistic she recorded pointed to the same conclusion.

The America she had been taught to despise as weak was instead impossibly strong.

The first letters home were permitted in October.

Prisoners were given paper, envelopes, and censored pens.

Most wrote cautiously, avoiding details that might be cut by the sensors.

Yet in between the careful lines, truths slipped through.

Yumiko wrote to her younger sister in Nagasaki.

I live in a place where hot water never ends.

Where bread is given freely, not measured, where the guards smile instead of scowl.

I cannot explain it, only that it is different than anything I knew.

Some women, however, refused to believe.

Rumors spread that the abundance was temporary, a calculated deception to soften them before interrogation or forced labor.

They will reveal their cruelty soon enough, whispered a former nurse, her voice trembling with both conviction and fear.

But each day passed, and no cruelty came.

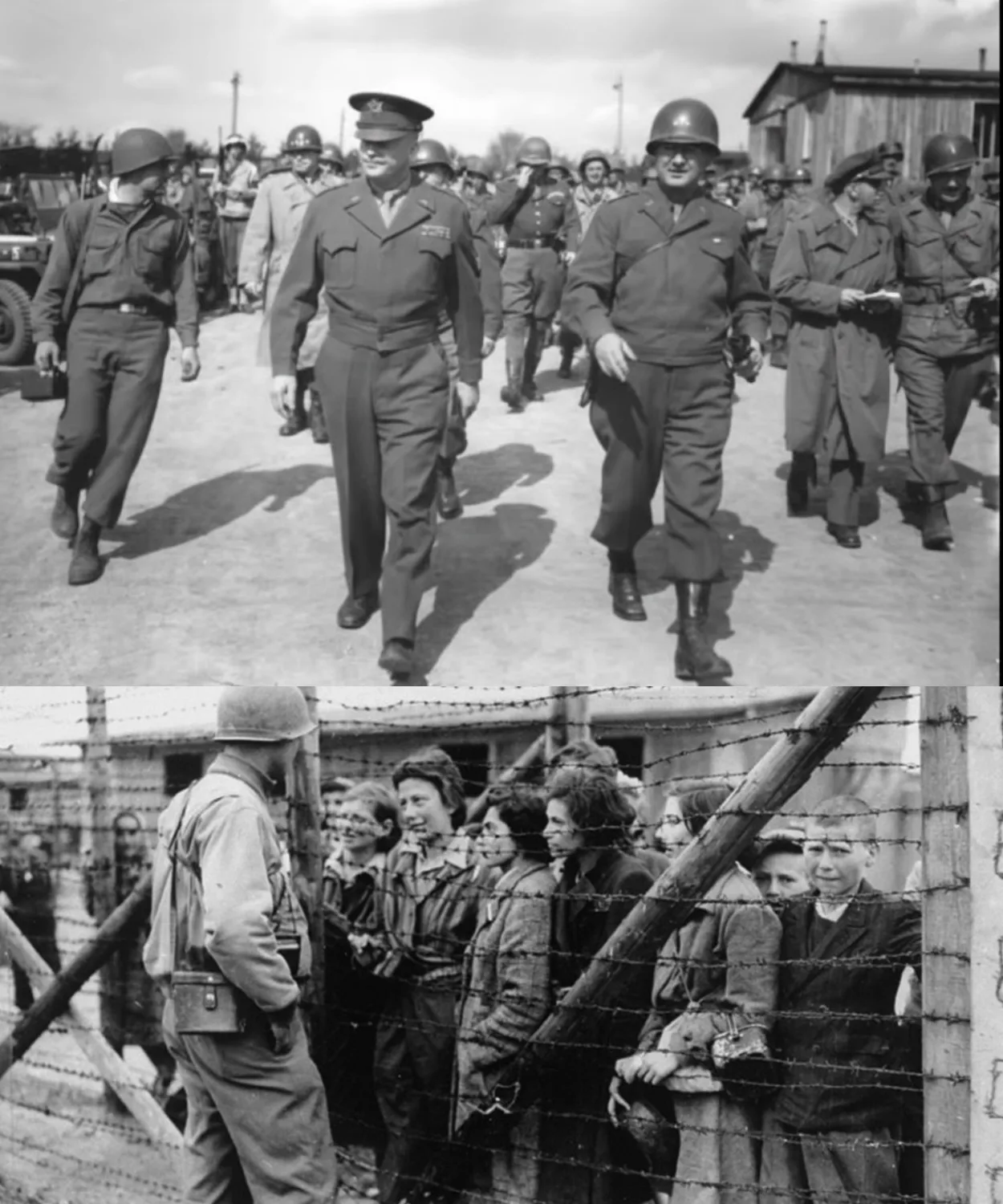

The most jarring contrast arrived with autumn when American civilians from nearby towns began delivering supplies to the camp.

They came not as enemies, but as ordinary workers, drivers, carpenters, clerks.

The Japanese women stared at them from behind the wire.

These men, not soldiers, not specially chosen, were taller, stronger, and healthier than the officers Japan had paraded in propaganda films.

Hioko wrote in her diary, “If even their common men are like this, then what of their armies? What of their factories? Perhaps our war was never winnable.” The emotional toll deepened.

Night after night, women lay awake, whispering their fears into the darkness of the barracks.

One admitted she no longer knew what to believe about her homeland.

Another wept, saying her children would think she had been corrupted by enemy lies.

Some began to grow angry, not at the Americans, but at the Japanese leaders who had told them fairy tales of superiority while sending them into a war they could not possibly win.

In November, the prisoners witnessed a camp baseball game between American guards.

The speed, power, and laughter of the players struck them like a blow.

Ko, standing among other prisoners at the fence, clenched her fists as tears burned in her eyes.

They run as if war never touched them, she said.

And we look at us, thin, broken shadows.

By winter’s first snowfall, the wall of propaganda had begun to crumble.

The women were no longer asking if they had been lied to, but how much had been hidden and why.

For Yumiko, Ko, and Hioko, the questions were no longer about America alone.

They were about Japan itself.

And in those quiet nights of cold Wisconsin air, when the guards laughter echoed across the camp and the smell of pine drifted through the barracks, each woman began to feel the same silent dread.

If our leaders betrayed us in war, what future can we trust when we return home? December 1945.

Snow blanketed Camp McCoy, turning the barbed wire fences into delicate lines of frost and softening the sharp edges of the barracks.

To the Japanese women inside, the whiteness felt like a cruel mirror, pure and endless, while their thoughts were muddied, heavy with betrayal and doubt.

The holiday season approached, though few of them recognized it at first.

The Americans decorated the camp with lights and wreaths.

The barracks warmed by stoves burning ceaselessly.

To the prisoners, the constant heat itself was another reminder of disparity.

Firewood in Japan had been scarce since 1943.

Here it was fed into the furnaces without hesitation, as if the forests were infinite.

On Christmas morning, the women were given gifts.

Small parcels with soap, chocolate, cigarettes, and even wool socks.

To Yumiko, the package felt heavier than any metal.

She turned the bar of soap over and over in her hands, remembering the weeks when she had washed in cold water with ashes and sand.

Beside her, Ko stared at her chocolate ration with wide eyes, whispering, “I dreamed of this when I was a child.

Now they hand it to me as if it were nothing.” The breaking point came a week later during a lecture given by an American officer as part of the re-education program.

Through an interpreter, he spoke casually of American wartime production, how the United States had built more than 96,000 aircraft in 1944 alone.

At first, the room fell silent.

Then, one woman gasped audibly, covering her mouth as if she had betrayed something sacred.

Hioko’s hand trembled as she copied the numbers into her notebook.

she calculated in the margins.

Japan’s best year had yielded barely 28,000 planes.

The gap was not just wide, it was infinite.

She dropped her pencil and whispered, “Then why did they send us to fight?” For days afterward, the women debated the lecture in hushed tones.

Some insisted the numbers were lies, exaggerations meant to crush their spirit.

But others, especially those who had seen American abundance with their own eyes, accepted the grim truth.

Yumiko recalled the cargo trucks arriving daily at the camp, each overflowing with supplies.

“If they can feed us like this, prisoners, what must they do for their soldiers?” she asked quietly.

The realization struck like grief.

Belief in their nation’s superiority had been their armor shielding them through hunger, bombing, and loss.

Now that armor cracked, leaving them exposed to the bitter cold of reality.

The psychological collapse was not uniform.

Some responded with denial, clinging to whispers that America’s prosperity was hollow, that its strength was soulless.

But others turned their anger inward toward Tokyo, toward Tojo, toward the men who had sent them into an unwininnable war dressed in lies.

One evening during roll call, a nurse named Sachiko suddenly broke down.

In front of the guards and her fellow prisoners, she shouted in Japanese, “They betrayed us.

They knew and they sent us anyway.” The barracks fell into silence.

No one argued.

No one comforted her.

The truth had already settled in their hearts.

Sachiko had only spoken it aloud.

That night, Yumiko wrote in her notebook, “We were told Americans are weak, yet I have seen their guards carry crates that would break five of our men.

We were told America is starving, yet I eat here more in one day than in a week at home.

” We were told their society is decadent, broken.

Yet the children I glimpse beyond the fences run strong, tall, and unafraid.

Every lie revealed feels like another death.

Ko, once defiant and quick to suspicion, grew quieter with each passing day.

She stopped dismissing the food as theater, stopped whispering rumors of stage delusions.

She began instead to study English phrases, her lips silently shaping foreign words as if they were keys to understanding the new world around her.

In January 1946, another shock came.

The camp organized a friendly exhibition.

A local baseball team played against American guards.

The women, curious, gathered at the fence to watch.

The game unfolded with speed and strength that defied their imaginations.

Men hurled balls across impossible distances, sprinted across bases with explosive energy, and laughed as if the war had been a mere storm now passed.

Heroko gripped the fence with both hands, the frozen metal burning her skin.

She remembered the posters in her classroom, cartoons of stooped, weak American soldiers.

Yet here, before her eyes, ordinary men moved like athletes, their muscles taught beneath clean uniforms.

She whispered a single word, lies.

By February, the despair deepened into something more complex, acceptance.

The Japanese women had not only lost their war, they had lost the illusions that sustained them.

Some began to wonder if defeat was in a twisted way liberation.

The snow melted.

The fields of Wisconsin turned to mud.

And with the thaw came a quiet but irreversible shift.

The prisoners no longer compared themselves to what they had been told.

They compared themselves only to what they saw.

And what they saw was a world larger, stronger, and more abundant than they ever believed possible.

March 1946, the Wisconsin winter receded, leaving behind fields wet with thaw and skies swollen with restless clouds.

Inside Camp McCoy, the rhythm of captivity continued.

But within the barracks, something heavier than snow pressed down on the women, the weight of recognition.

For months, they had whispered questions in the dark.

Now the answer stood before them in daylight.

Undeniable.

Yumiko Aai, once steady and composed, began to unravel.

In the infirmary, she stitched wounds and measured temperatures, but her thoughts wandered endlessly.

One afternoon, while disposing of unused bandages, she stopped and stared at the clean white cloth in her hands.

In Nagasaki, she had watched children die because there was nothing left to dress their burns.

Here, such bandages were thrown away without a thought.

She dropped the cloth into the bin and collapsed against the wall, tears streaking her cheeks.

Margaret Collins rushed to her side, but Yumiko only shook her head, whispering, “Why? Why did they tell us we were winning?” Kikosato’s silence grew heavier.

She had been defiant at first, quick to argue against the others doubts.

Now she sat alone after meals, practicing English words in the margins of old newspapers.

When Yumiko asked her why, Kiko looked up with eyes shadowed by exhaustion.

Because if I learn their words, maybe I will finally understand how they became this.

Hiro Nishida’s notebook grew thick with pages, numbers, sketches, fragments of overheard English, even maps drawn from memory.

But instead of clarity, her studies brought despair.

The gap between America’s strength and Japan’s weakness was too vast to measure.

One night, she tore out a page and read it aloud to the barracks.

In 1944, America built more ships than Japan had in its entire fleet.

In one year, they produced more steel than we produced in the whole war.

and we were told to fight until death as if our sacrifice could bend numbers written in iron.

The barracks fell silent.

Some women wept.

Others stared at the floor, faces pale with rage.

The climax came with the arrival of news from home.

In April, Red Cross officials brought reports of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Photographs of flattened cities, survivors with kloid scars, children living among ruins.

Many of the prisoners had heard rumors, but the images cut deeper than words.

Hioko dropped her notebook to the ground, unable to hold the picture of her homeland’s ashes.

Yumiko, who had family in Nagasaki, sat frozen as she stared at a blurred image of a city she once knew.

Smoke still curled from collapsed houses and the skeleton of the cathedral pierced the sky like a broken tooth.

Her voice cracked as she whispered, “My home is gone.” For days afterwards, the camp seemed muted.

Guards spoke softly.

Meals passed in silence.

Even the laughter of children from nearby towns felt distant, muffled.

And yet, amidst the grief, a new thought emerged.

If everything they had been told was false, if their leaders had lied about America’s weakness, about Japan’s invincibility, about the war’s purpose, then perhaps loyalty itself was a chain.

One evening, Ko stood at the barracks window, the sunset staining the snow melt red.

She turned to the others and said, “They took everything from us.

Our brothers, our homes, our pride.

But here I see children running free, women treated with respect, food in every hand.

If this is defeat, then what was our victory ever supposed to be?” Her words broke something open.

Women who had remained silent began to speak, to rage, to confess their anger, not at the Americans, but at Tokyo, at the emperor’s ministers, at the system that demanded blind obedience.

That night, Hioko wrote one final line in her notebook before closing it.

I was not defeated by America.

I was defeated by the lies of my own country.

For the first time since their capture, the women no longer saw themselves only as prisoners.

They were witnesses, living evidence of a war built on illusions.

And in that realization, painful and raw, lay the beginning of transformation.

Summer 1946, the camp grass had grown tall, green against the wooden barracks where Japanese women lived out the long months of their captivity.

By then, life in Camp McCoy no longer felt like a temporary passage, but a strange second world, an island of order and abundance, standing in brutal contrast to the ashes of home.

The women had changed.

Yumiko no longer cried when discarding supplies in the infirmary.

Instead, she saved scraps of cloth, passing them quietly to others as momentos, tokens of survival.

She had learned to speak with Margaret Collins in halting English, asking questions not just about medicine, but about America’s women, their freedoms, their choices.

The answers unsettled her even more than the food rations.

Ko, once the sharp tonged skeptic, now taught herself English with determination, repeating words late into the night.

To her, language was a weapon, not of war, but of survival.

She filled notebooks with phrases, freedom of speech, equal rights, newspaper press, words she had never heard in Japan.

Hioko no longer measured America only by numbers.

Her notebook became a diary filled with reflections on morality and truth.

She wrote, “Our defeat is not simply military.

It is spiritual.

We were children in a house of mirrors, shown only what our leaders wished us to see.

Here in the land of the enemy, I finally see my own face.

In August, nearly a year after their capture, word came that many prisoners would soon be repatriated.

The announcement stirred conflicting emotions.

Relief at the thought of home, dread at returning to a country ruined by fire and famine.

Some women whispered of staying, of finding ways to build lives in America.

Others longed desperately for family, even if what awaited them was rubble.

On the night before departure, the three friends, Yumiko, Ko, and Hioko, sat together beneath the glow of the camp’s flood lights.

The air was warm, filled with the hum of insects.

They spoke quietly, not of the past, but of the future.

Yumiko said she feared being unable to reconcile the two worlds, the hungry Japan of her memories and the abundant America of her captivity.

Ko admitted she no longer knew what it meant to be loyal to a nation that had lied so thoroughly.

Hioko said nothing at first, then finally whispered, “Perhaps our duty now is not obedience, but truth.

If we return with open eyes, maybe we can teach others what we have seen.

The train that carried them east toward the Pacific was filled with silence.

Each woman pressed her forehead against the glass, watching the American landscape unfold.

Vast fields, endless factories, bridges of steel.

They knew they would never forget.

When at last their ship departed for Japan, the women stood on deck, staring back at the receding shoreline.

They had come as enemies, lived as captives, and left as something else entirely.

Witnesses to the collapse of illusion and to the fragile strength of truth.