Texas, 1945.

The shower facility at Camp Swift stood empty most mornings.

Oh, the water ran hot and soap was plentiful.

16 German women prisoners arrived in shifts, each waiting until the others had finished, refusing to undress together despite the privacy screens and the guard’s absence.

The American nurses noticed, but didn’t understand.

Not until Dr.

Margaret Walsh conducted the medical examinations and saw what the women had been hiding beneath their prisons dresses.

Scars that told stories of suffering beyond combat.

Marks that explained the shame, the silence, the desperate need for solitude.

What the Americans did next would break through years of trauma and propaganda, proving that compassion could exist even between enemies.

The spring air carried meat and dust across central Texas, where Camp sprawled beneath the sky so vast it swallowed perspective.

The facility had been built to house German prisoners of war.

Thousands of men captured in North Africa and Europe who worked in the surrounding farms and ranches while waiting for peace to bring them home.

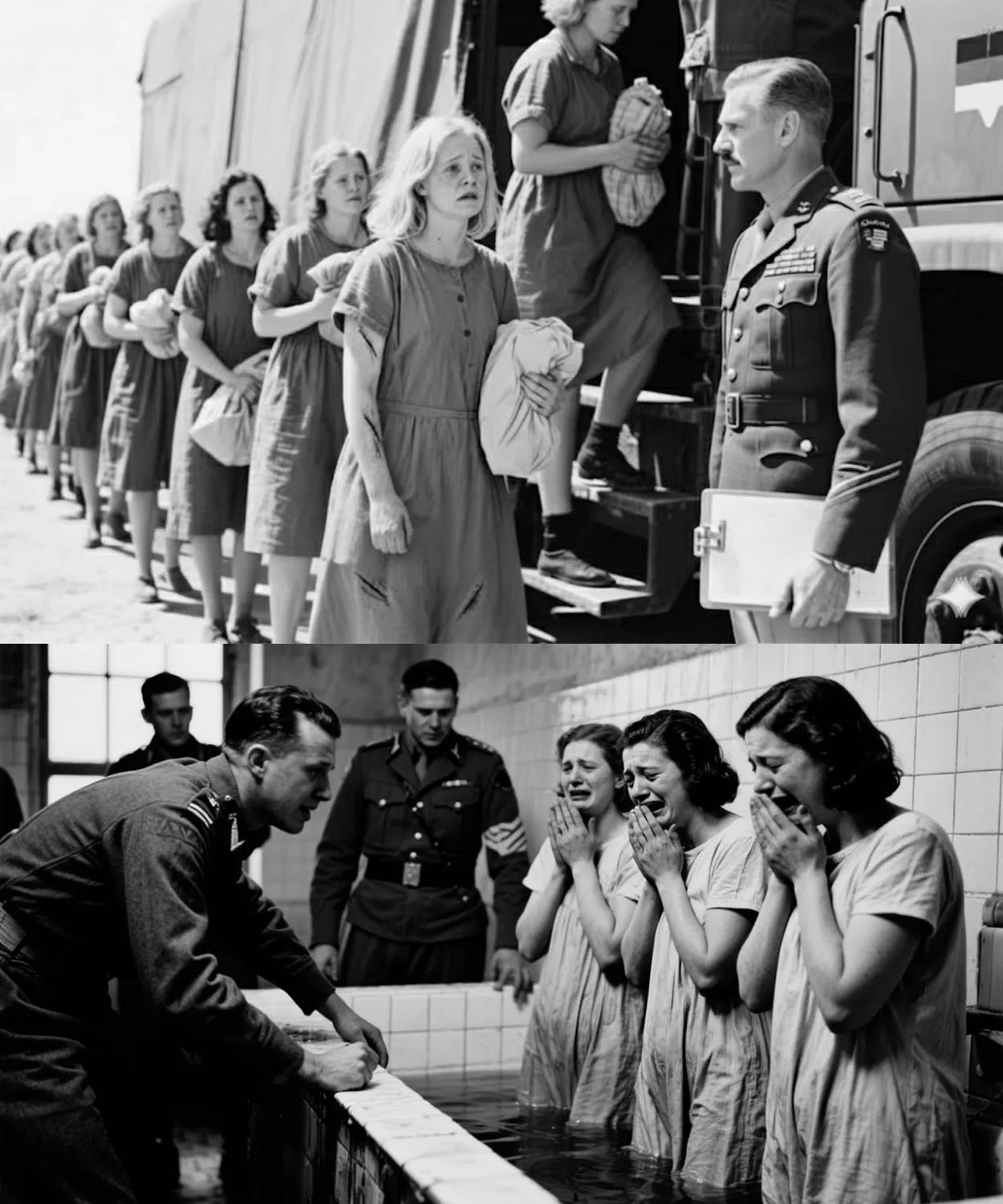

But in March 1945, something unusual arrived at transport of 16 German women transferred from a processing center on the east coast.

Their papers marked with classifications that offered more questions than answers.

They came off the truck in silence.

Standardisssue dresses, gray and shapeless, hung on frames too thin for the fabric.

They carried small cloth bags containing whatever personal items had survived confiscation and inspection.

Their faces showed exhaustion that went deeper than travel, a weariness that lived behind the eyes and made them look older than their paperwork suggested.

Lieutenant Colonel James Morrison watched their arrival from his office window.

He was 47, a career officer who’d spent the war managing P facilities rather than seeing combat, a role that suited his belief in order, proper treatment, and the Geneva Conventions as both legal requirement and moral foundation.

Female prisoners were rare, complicated, requiring separate housing and careful protocols that his staff wasn’t entirely prepared to handle.

He’d arranged for the women’s barracks to be as comfortable as circumstances allowed, actual beds with mattresses, windows that opened, a small common area with chairs and a table.

The shower facility was adjacent, newly constructed with individual stalls and privacy curtains, hot water piped from the camp’s central system.

By P camp standards, the accommodations were generous, humane even.

But the women received these arrangements with suspicion rather than relief, as if kindness itself might be a trap.

Captain Margaret Walsh conducted the initial medical examinations.

She was 34, one of the few female doctors in military service, who defought for her position and proved herself repeatedly in field hospitals where gender mattered less than coidence.

She approached her work with careful professionalism that masked deeper compassion, understanding that examination could be violation if not handled with respect for dignity and trauma.

The first woman she examined was named Greta Fischer, 28 years old, according to her papers, though her face suggested more years, had passed than any calendar could measure.

She undressed slowly, carefully, with movements that spoke of pain managed rather than healed.

Walsh tried to maintain professional neutrality, but what she saw made something cold settle in her chest.

Scars covered Gita’s torso, back, and legs.

Burns that had healed badly, creating thick raised tissue.

Marks that suggested impact trauma batons or fists or boots applied with systematic precision.

evidence of injuries that had been left untreated, that had become infected and healed wrong, and had damaged not just skin, but the tissue and muscle beneath.

“Where did this happen?” Walsh asked gently, her German functional enough for basic communication.

Greta stared at the wall, her expression carefully blank.

“A detention facility in Poland? I was held there for 18 months before transfer.

” “What were you detained for? political activities, the answer was automatic, rehearsed, revealing nothing beyond the fact that explanation was dangerous even now, even here, even after everything.

Walsh documented the injuries, measured and photographed, and noted their locations with clinical precision.

But beneath the professional procedure, she felt rising anger at what had been done to this woman, at the systematic cruelty that had created such damage, at the institutions that could transform human beings into canvases for suffering.

The other examinations revealed similar patterns.

All 16 women carried scars, marks, evidence of trauma that went beyond combat or accident into something more deliberate.

They’d been prisoners before becoming prisoners of war, held in facilities where treatment violated every principle of human dignity, where bodies became tools for punishment and interrogation and the extraction of whatever compliance was required.

And they were ashamed.

Walsh saw it in how they moved, how they avoided eye contact, how they dressed and undressed with movements designed to minimize exposure.

They carried their scars as if the marks were personal failures rather than evidence of survival.

As if the damage done to them reflected something broken in their character rather than in the systems that had damaged them.

The shower situation became apparent within days.

The facility was designed for communal use multiple stalls with curtains, a common changing area.

Efficiency built into the architecture, but the women refused to use it together.

They came in shifts, each waiting until the others had finished.

Sometimes standing in the corridor for 30 minutes or more just to avoid being in the same space while undressed.

Nurse Lieutenant Sarah Henderson noticed first.

She was 26 from Ohio who’d volunteered for military service after her brother was injured at Anzio.

She supervised the women’s daily routines, managed their medical needs, and tried to understand the silent communication system they developed where looks and gestures replaced words whenever possible.

They won’t shower together, Henderson reported to Walsh one morning.

They take turns one at a time, even though the stalls have curtains and there’s complete privacy.

It’s taking hours each day, disrupting the entire schedule.

Walsh thought about the scars, about what she documented during examinations.

They’re protecting themselves, she said quietly, from judgment, from questions, from having to explain or defend or relive whatever created those marks.

Being alone means they don’t have to perform normaly, don’t have to pretend the damage doesn’t exist.

Henderson absorbed this.

Her young face showing the particular pain of someone encountering cruelty.

they’d never imagined possible.

What do we do? We give them time, Walsh said.

We respect their need for privacy.

We don’t force proximity until they’re ready.

But she knew time alone wouldn’t heal what had been broken.

These women needed more than just physical safety.

They needed proof that the world could contain something other than cruelty.

that other human beings could witness their damage without turning it into spectacle or judgment or further violation.

The women worked in the camp laundry, a large facility where military uniforms and linens were processed in industrial quantities.

The work was hard lifting heavy wet fabric, operating machinery, standing for hours in steam and heat, but it was also relatively solitary.

Each woman assigned to a specific station where she could focus on tasks rather than interactions.

Greta worked the pressing station, ironing uniforms with careful precision.

The heat from the press reminded her of things she didn’t want to remember.

But she’d learned to separate physical sensations from emotional responses, to let her body react while keeping her mind carefully neutral.

Survival had required such divisions, such compartmentalization, and the skills didn’t disappear just because circumstances changed.

Beside her at the folding station worked on a RTOR.

31 years old from Munich, arrested in 1943 for harboring someone the regime wanted to find.

She’d been held in various facilities for 2 years before transfer to American custody.

moving through detention centers where treatment ranged from neglect to active cruelty, where food was scarce and medical care non-existent, and survival required becoming smaller, quieter, less visible.

They worked in silence mostly, the machinery loud enough to discourage conversation.

But sometimes during breaks they talked in careful fragments about neutral topics, weather, work assignments, the peculiar emptiness of Texas landscapes that seemed to stretch forever without the boundaries and borders that European geography imposed.

“Do you think it’s real?” Anna asked one afternoon, her voice barely audible over the machinery.

the kindness here, the decent treatment, or is it temporary, something that will stop once we’re not useful anymore? Greta considered this.

She’d learned not to trust easily, not to mistake temporary circumstances for permanent safety.

I don’t know, she finally said, “But I think maybe it doesn’t matter whether it’s permanent.

Maybe we just accept what’s offered while it lasts without expectations about tomorrow.” Anna nodded, understanding the philosophy of survival that valued present moment over uncertain future.

They returned to work, pressing and folding, moving through the mechanical routines that organized their days into manageable segments.

Dr.

Walsh began meeting with the women individually, offering medical followup that served as cover for deeper conversations about trauma and recovery.

She wasn’t a psychiatrist.

Her training was in general medicine, surgery, emergency care.

But she understood that healing required more than treating physical symptoms, that the scars on their bodies connected to wounds in their minds that might never fully close.

She met with Greta on a Tuesday afternoon in late March.

They sat in the small medical office, afternoon light filtering through windows that actually open that let in air and sound and the smell of grass.

Outside distant voices called across the parade ground and the normaly of it felt surreal after years of places where windows were luxuries and outdoor air was rationed like food.

How are you adjusting? Walsh asked.

Greta shrugged.

As well as can be expected.

The work is hard but fair.

The food is adequate.

No one has hurt us.

That last part shouldn’t be noteworthy.

Walsh said quietly.

Not being hurt should be the baseline, not an achievement worth mentioning.

Perhaps in your world, Gret replied.

In mine, it’s been remarkable enough to mention.

They sat with that statement for a moment.

A distance between their experiences laid bare in simple acknowledgement.

Walsh had seen combat trauma, had treated soldiers with injuries, both physical and psychological, but she’d never been imprisoned, never been systematically broken down by institutions designed to extract compliance through suffering.

Her understanding was academic, professional, fundamentally limited by the fact that she’d never lived inside that particular nightmare.

the showers.

Walsh finally said, “I understand why you prefer privacy, but I’m wondering if there might be value in the opposite approach in being seen by others who understand, who carry similar marks, who wouldn’t judge because they know firsthand what those scars represent.

” Greed’s expression hardened.

“You think we should display our damage like badges? Compare wounds like soldiers trading war stories?” No, Walsh said carefully.

I think you might find relief in not having to hide.

In discovering that the shame you carry isn’t justified, that the scars don’t mean what you’ve been taught they mean.

That survival itself, regardless of what it cost, is something worth honoring rather than concealing.

Greta looked at her hands at the burned scars that wrapped around her fingers like cruel jewelry.

“You don’t understand what it’s like,” she said quietly.

To have your body become evidence of everything done to you.

To carry proof of violation that never fades, never disappears, never lets you forget even for a moment.

The scars aren’t just marks.

They’re constant reminders of powerlessness, of being reduced to object rather than person.

Of having choices taken away until even your flesh doesn’t belong to you anymore.

Walsh felt the weight of that truth, the impossibility of her position as someone trying to help while standing outside the experience she was addressing.

You’re right, she said.

I don’t understand, not fully, but I see how you’re surviving, how all of you are moving through each day carrying weight that would destroy most people.

And I’m wondering if that strength might be multiplied rather than diminished by sharing it by letting others witness, not just the damage, but the fact that you’re still here, still functioning, still human despite everything that tried to prove otherwise.

The idea came to Walsh late one night, lying awake in her quarters while thinking about shame and scars and the particular ways that trauma isolated its victims.

She couldn’t force the women to trust each other, couldn’t mandate vulnerability or connection, but she could create circumstances where such trust might develop organically, where the choice to be seen was offered rather than demanded.

She discussed it with Henderson the next morning over weak coffee in the medical office.

What if we organized a dedicated bathing time? Walsh proposed not communal showers but a private session where all 16 women have access to the facility simultaneously.

Stalls available, curtains provided, but also the option to be less private if they choose.

No pressure, no requirements, just opportunity.

Henderson considered this.

You think they’d take advantage of it? Actually choose to shower together when they’ve been avoiding exactly that situation.

Some might, not all, maybe not even most.

But if even a few women discover that being seen by others who understand doesn’t result in judgment or shock or further trauma, it might open doors that have been locked since their imprisonment.

And if it backfires, if the experience just reinforces their shame, makes them even more isolated, then we learn something about what doesn’t work and we try something else.

But doing nothing, just allowing them to continue hiding from each other indefinitely.

That’s not neutral.

That’s a choice that maintains the isolation Toronto created.

Henderson nodded slowly.

When do we start? Tonight, Walsh said.

After work assignments end before evening meal, we’ll announce it as optional private bathing time.

Make it clear that participation is voluntary, that they can use the stalls individually or not.

We give them the choice and see what they do with it.

The announcement was made that afternoon during the AFO brief period between work shifts and dinner.

Henderson explained the arrangement carefully, emphasizing the voluntary nature, the continued availability of privacy screens, the lack of any requirement or expectation.

The women received the information in silence, no questions, no comments, just the blank expressions they perfected during years of learning.

that revealing reactions could be dangerous.

Henderson couldn’t tell if the idea intrigued them or terrified them or simply registered as another incomprehensible American gesture.

At , the shower facility was prepared.

Fresh towels, new bars of soap, hot water confirmed operational.

Walsh and Henderson would be present, but not intrusive.

available if needed, but primarily there to ensure safety rather than supervise behavior.

The women arrived gradually, individually, maintaining the pattern they’d established.

Greta came first, carrying her towel and soap, moving toward the farthest stall with practiced efficiency.

Then Anna, then Maria, then others, each selecting a separate space, drawing curtains, maintaining the isolation that felt safer than exposure.

Walsh and Henderson waited near the entrance, saying nothing, just present as witnesses to whatever might or might not develop.

For the first 10 minutes, nothing changed.

Water ran in separate stalls, steam filled the space, and privacy was maintained with the same careful precision the women had demonstrated since arrival.

Then Greet’s curtain opened.

She stepped out partially, still wrapped in her towel, but visible present, no longer completely hidden.

She looked at Anna’s closed curtain, then at Maria’s, then at the other closed stalls where water ran and women bathed in solitude.

I’m tired of hiding, she said, her voice cutting through the sound of running water.

I’m tired of pretending these scars don’t exist.

Tired of carrying shame for damage I didn’t choose.

Tired of performing normaly for people who can’t possibly understand what we’ve survived.

Silence greeted this declaration.

The water continued running, but no one spoke.

No curtains moved.

Greta took a breath, then lowered her towel, revealing the scars that covered her torso and back.

Burns, impact marks, the physical record of 18 months in detention facilities where her body had become canvas for systematic cruelty.

This is what they did, she said quietly.

This is what I carry, and I’m not ashamed anymore because I survived.

The scars are proof of that proof that they tried to break me and failed.

that I’m still here despite everything they took.

That survival itself is victory even when it comes with marks.

For a long moment, nothing happened.

Then Anna’s curtain opened.

She stood there also wrapped in a towel, tears running down her face.

“I have them too,” she whispered.

“Different locations, different causes, but the same result.

evidence that I was powerless, that my body was used to punish my choices, that I carry permanent reminders of temporary circumstances that lasted too long.

She dropped her towel, revealing her own scars burns across her shoulders, impact marks on her ribs, evidence of treatment that violated every principle of human dignity.

One by one, other curtains opened.

Maria stepped out, showing scars from electrical burns that had been used during interrogations.

Helga revealed marks from prolonged restraint in positions that had damaged muscles and left permanent indentations.

Eva displayed evidence of medical experimentation that had left her back, covered in surgical scars that had never properly healed.

16 women standing in steam and hot water and the strange safety of a Texas shower facility, showing each other damage they’d been hiding.

Marks they’ved been carrying in isolation.

Proof that they’d survived things designed to destroy them.

No one spoke for a long moment.

They just looked at each other, seeing scars that matched their own.

Evidence that they weren’t alone in their damage.

proof that survival could include permanent marks without meaning permanent defeat.

And Greta began to cry.

Not quiet tears, but deep sobs that shook her entire body, releasing something that had been held too tightly for too long.

Anna moved toward her, and suddenly they were holding each other.

Two women who deep been strangers a month ago now connected by shared experience of trauma and survival and the strange relief of being seen by someone who understood.

Others joined creating a circle of damaged bodies and intact spirits holding each other while water ran and steam rose and something fundamental shifted in how they understood their own stories.

Walsh watched from the entrance, tears running down her own face.

Henderson stood beside her, equally emotional.

Both of them witnessing something they dehoped for but hadn’t dared to expect.

A moment when isolation transformed into connection, when shame dissolved in the face of shared experience.

When survival stopped being something to hide and became something worth acknowledging.

After that evening, everything changed.

The women began showering together regularly, not hiding their scars, but treating them as simple facts, evidence of history rather than causes for shame.

They talked while bathing, shared stories about what had happened and how they’d survived, built community through vulnerability rather than through pretending damage didn’t exist.

They started eating together in the mess hall, sitting at a long table where conversations happened in German mixed with broken English, where laughter occasionally broke through the careful seriousness they’d maintained.

They helped each other with difficult tasks, offered support during moments when trauma resurfaced, created informal networks of care that operated alongside the official medical treatment.

Greta and Anna became particularly close.

Their friendship deepening through shared understanding that went beyond words.

They worked adjacent stations in the laundry, spent evenings together reading or talking or simply sitting in comfortable silence.

They wrote letters jointly, combining their English skills to communicate with authorities about their cases, about repatriation plans, about what waited for them when they eventually went home.

The camp chaplain, Captain Robert Hayes, noticed the transformation.

He was 52, a Methodist minister from Tennessee who’d volunteered for military service after Pearl Harbor, who believed his role was to offer spiritual support regardless of denomination or nationality.

He began holding optional services for the women, non- sectarian gatherings where anyone could attend, regardless of religious background.

Greta came once, more from curiosity than faith.

She’d lost whatever religious belief she’d carried before detention, couldn’t reconcile any benevolent deity with what she’d witnessed and experienced.

But she appreciated Hayes’s approach, gentle, non-demanding, focused more on community than doctrine.

After the service, Hayes asked if she’d talk with him.

They sat in his small office, afternoon light filtering through windows, and he asked simple questions about her experience, her survival, her plans for whatever came next.

I’ve been thinking about forgiveness, Greta said at one point.

Whether it’s possible, whether it’s necessary, whether the people who damaged us deserve any consideration beyond punishment.

Hayes was quiet for a moment before responding.

Forgiveness isn’t really about them.

He finally said, “It’s about you, about whether carrying anger and hatred serves any purpose beyond keeping you connected to people who do and deserve space in your consciousness.

So I should just forget.

Pretend the scars don’t exist, that the damage was trivial.

” “No,” Hayes said firmly.

“Remember everything.

Document it.

Testify to it.

Make sure history records what was done.

But separate the remembering from the emotional attachment to revenge.

The scars are evidence, but they do have to be chains that keep you bound to your capttors even after you refree.

Greta thought about this for a long time.

I don’t know if I can do that, she admitted.

The anger feels like the only thing keeping me upright sometimes, like if I let it go, I’ll collapse completely.

Then maybe you’re not ready yet, Hayes said.

And that’s okay.

Healing doesn’t follow schedules.

It happens when it happens in its own time through processes that can’t be forced or rushed or completed on demand.

In May, Walsh organized a group therapy session, though she didn’t call it that, knowing the term might create resistance.

She framed it as an informal discussion about adjustment, recovery, plans for repatriation.

All 16 women attended, gathering in the common area of their barracks.

sitting in a circle on whatever chairs and benches could be assembled.

Walsh started by acknowledging what they’d all survived, the shared experience of detention and trauma and the long difficult process of moving forward.

Despite damage, it would never fully heal.

Then she opened the floor for anyone who wanted to speak.

Silence initially, the familiar caution about revealing too much, about trusting the safety of this moment.

Then Maria began talking.

She described her arrest, political activity, involvement with resistance networks, choices she’d made knowing they carried risks but believing they were necessary.

She described interrogation methods designed to extract information and break wall simultaneously.

She described months in detention facilities where time lost meaning, where days blurred together in endless repetition of suffering and small acts of defiance that kept identity intact.

What I remember most, she said quietly, isn’t the pain exactly.

It’s the isolation.

Being kept separate from other prisoners, never knowing if anyone else was going through similar experiences, never having the relief of shared understanding.

The physical damage was terrible, but the psychological isolation was worse.

The sense that I was alone in my suffering, that no one could possibly understand what was happening inside my head while they destroyed my body.

Others nodded, recognizing the particular torture of enforced isolation, of being denied connection exactly when connection was most necessary.

Anna spoke next, describing similar experiences in different facilities, emphasizing how the guards had weaponized shame, making prisoners feel that the damage done to them reflected personal failure rather than institutional cruelty.

They wanted us to believe we deserved it.

She said that the treatment was punishment for our choices, that the pain was justice rather than abuse.

And part of me believed them, internalized the shame they were trying to create, started thinking that maybe I was fundamentally broken in ways that justified how they treated me.

Helga talked about arriving at Camp Swift, about expecting similar treatment, about the cognitive dissonance of finding kindness instead of cruelty, decent conditions instead of deliberate suffering.

I didn’t trust it, she admitted.

I kept waiting for the trap for the moment when the facade would drop and we rediscover this was just a more sophisticated form of torture.

It took weeks before I could accept that maybe Americans actually meant the Geneva conventions they claimed to follow.

Ava described the shame of carrying scars, of having her body become permanent evidence of temporary circumstances, of feeling that everyone who saw her would know what had been done and would judge her for it.

That’s why I couldn’t shower with you all initially, she said.

Not because I was ashamed of what I’d survived.

Exactly.

But because I was afraid you’d see the marks and think less of me, think I was damaged goods.

Think I was weak for not somehow preventing what happened.

But we all carried the same marks, Greta said.

All of us damaged in similar ways.

All of us surviving similar nightmares.

The shame was never justified.

It was just another way they controlled us.

Another weapon they used to keep us isolated and powerless.

The conversation continued for hours.

Each woman adding pieces to the collective narrative.

Building through shared testimony a larger story about survival and damage and the slow difficult process of reclaiming identity.

After institutions tried to erase it, Walsh mostly listened, occasionally offering medical perspective on how trauma affected both body and mind, how healing required addressing both physical symptoms and psychological wounds simultaneously.

But primarily she just witnessed understanding that the real therapy was happening between the women themselves through the simple act of being heard and understood by others who knew firsthand what survival cost.

Jung brought news of repatriation schedules.

The women would be processed through various classifications, investigated for potential connections to regime activities, eventually returned to whatever remained of their homes.

The timeline was uncertain.

weeks or months depending on bureaucratic efficiency and the larger chaos of postwar Europe where borders shifted and governments dissolved and millions of displaced people tried to find their way back to places that might no longer exist.

Greet’s case was reviewed by a tribunal examining her arrest record, detention history, the charges that had led to her imprisonment.

The investigators found no evidence of wrongdoing her political activities had been humanitarian rather than hostile, helping targeted groups escape persecution rather than supporting enemy operations.

She was cleared for immediate repatriation, scheduled for departure in July.

She received the news with mixed emotions.

Part of her wanted desperately to go home, to see Germany again, to find whatever fragments of her previous life might be salvageable.

But another part recognized that home no longer existed, that the place she’d known was gone, that repatriation meant confronting loss on a scale she could barely imagine.

Gunna was cleared at the same time, her case similarly reviewed and resolved.

They would travel together.

Two women who’d been strangers four months ago, now bound by friendship, forged through shared trauma and recovery.

The other women received various timelines, some quick clearances, others complicated by questions about their activities or associations.

But eventually, all would go back.

All would face the enormous task of rebuilding lives from whatever remained after years of war and detention and systematic attempts to destroy everything that made life worth living.

On their final night at Camp Swift, the women gathered for an informal farewell.

No official ceremony, no speeches, just time together in the barracks common area, sharing coffee and the peculiar awareness that this community built from necessity and trauma and unexpected kindness would soon dissolve.

Greta stood and spoke, her voice carrying the weight of everything they’d experienced together.

“When we arrived here, I was ashamed,” she said.

ashamed of my scars, ashamed of my weakness, ashamed that I carried permanent evidence of what had been done to me.

I thought the marks meant I was broken, that survival had come at a cost that made me less than whole.

She paused, looking at each woman in turn.

But you taught me something different.

You showed me that scars are evidence of survival, not failure.

That carrying damage doesn’t mean being destroyed.

that we can acknowledge what was done to us without letting it define everything we become afterward.

The shame was never ours to carry.

It belongs to the people who created these marks, not to those of us who survived them.

Maria stood next.

Before this place, I thought I was alone.

At my experience was unique, that no one could possibly understand what I carried.

But here, I learned that survival creates its own community.

that shared trauma can become foundation for connection rather than isolation.

You all saved me in ways that have nothing to do with physical rescue and everything to do with making me feel human again after so long being treated as object.

One by one, others spoke offering gratitude, sharing hopes for the future, acknowledging that this temporary community had provided something essential that might not be replaceable once they scattered back across Europe.

Eva spoke last.

The Americans here, Dr.

Walsh, Nurse Henderson, all of them, they showed us that our enemies could contain more compassion than our own institutions.

That’s a strange thing to carry forward.

The knowledge that strangers treated us with more dignity than our own leaders.

But it’s also proof that humanity persists even in context designed to extinguish it.

That kindness can exist between people who should.

according to propaganda hate each other completely.

The departure came on a morning in late July.

A truck arrived at dawn and the first group of women prepared to leave.

Greta and Anna stood with their small bags, wearing civilian clothes donated by the Red Cross, looking at the barracks and the shower facility and the laundry where they’d worked for 4 months.

Walsh came to see them off.

She’d brought small gifts photographs.

she’d taken of the group, copies of medical records documenting their treatment in case such documentation proved useful, letters of reference describing their character and work ethic during imprisonment.

Thank you, Greta said, the words inadequate for what she was trying to express.

for seeing us, for treating the scars as evidence of survival rather than proof of damage, for giving us space to heal without demanding we heal on your timeline or according to your expectations.

Walsh nodded, emotion-making speech difficult.

Thank you for trusting us, she finally managed.

For being willing to try vulnerability despite every reason to stay hidden.

for teaching us that healing can happen even after damage that seems permanent.

They embraced captor and captive, doctor and patient, two women who deb strangers months ago, now connected by the strange intimacy of trauma, witnessed and addressed.

Anna hugged Henderson, whispering gratitude for the hundreds of small kindnesses that had made survival bearable.

That had proven daily that humans could choose compassion, even in contexts structured around control.

The truck departed, carrying women back toward whatever waited in Europe.

Walsh and Henderson watched until it disappeared into Texas distance.

Both of them feeling the peculiar loss that comes from investing deeply in people you know you’ll l likely never see again.

Greater Richtor returned to Stogart in August 1945.

The city was ruins, barely recognizable, but people were returning, rebuilding, trying to construct futures from wreckage.

She found work teaching at a school being organized for children whose education had been interrupted by war.

Using her own experience of disruption and recovery to help students process trauma they couldn’t articulate.

She never married, never had children, carried her scars as permanent reminders of what she’d survived and what survival cost.

But she built a life that included friendship, purpose, and the quiet satisfaction of helping others find their way through darkness she knew intimately.

Anna settled in Munich, working with refugee organizations, helping displaced persons navigate bureaucratic systems and access resources.

She corresponded regularly with Greta, maintaining the friendship that had begun in a Texas shower facility.

Both women understanding that some connections transcend geography and circumstance.

They returned to Camp Swift together in 1963, 18 years after their release.

Walsh was still there, now a major, still conducting examinations and offering care to new generations of personnel.

Henderson had left military service, but returned for the reunion, curious to see what had become of the women she’d helped care for.

The four of them walked through the facility, which had been converted to different purposes, but retained the basic architecture.

They stood in the shower building, now used for different populations, but still recognizable, and remembered that evening when isolation had transformed into connection.

I think about that night often, Greta said.

When I finally stopped hiding, when all of us showed each other the damage we’d been carrying in private, it was the beginning of understanding that survival itself was victory, that the scars didn’t have to define us, even though they dee always be part of us.

It was one of the most powerful moments I’ve witnessed,” Walsh said.

Watching you all choose vulnerability despite every reason to stay protected.

Seeing connection form between people who’d been systematically isolated.

Understanding that healing could happen even after damage that seemed permanent.

They visited the cemetery where camp personnel who’ died during service were buried, laying flowers and offering respect for those who’d served with compassion rather than cruelty.

They ate together at a local diner, sharing stories about the decades that had passed, about losses and victories and the strange geography of survival.

Before leaving, Greta gave Walsh a gift, a book she’d written about her experiences, published in German, but being translated for English release.

It documented her arrest, detention, and eventual recovery, with particular focus on those four months at Camp Swift, when Americans had shown her that enemies could contain compassion.

You saved us, Greta said simply, not from death necessarily, but from the belief that humanity had been completely extinguished by war.

You proved that people could choose kindness, even in context structured around control, at healing was possible, even after damage that seemed permanent.

Walsh read the dedication that night.

For Dr.

Margaret Walsh and the staff of Camp Swift, who taught me that scars are evidence of survival, not proof of defeat, who gave me permission to be seen when I’d learned to hide.

Who showed me that shame was never mine to carry.

A shower facility was demolished in 1975, replaced by newer construction, but photographs remained, archived in military records, showing the building where 16 women had learned that damage didn’t have to mean destruction.

That visibility could bring relief rather than judgment.

That survival itself, regardless of cost, was worth honoring.

Greta died in 1987 at age 70.

her body finally giving out after decades of carrying scars that had never fully healed.

Her funeral was attended by other survivors, by students she taught, by people whose lives she’d touched through her willingness to share her story rather than hide it.

Anna spoke at the service, remembering their friendship a moment in the shower when Greta had dropped her towel and declared she was tired of hiding.

She taught me that courage isn’t the absence of shame.

Anna said, “It’s the willingness to be visible despite shame, to trust that being seen by the right people can transform damage into testimony.

” Walsh attended, now retired, traveling from Texas to Munich, to pay respects to a woman who de taught her as much about healing as any medical textbook.

She placed flowers on the grave, remembering that 16-year-old doctor, who de thought she understood trauma, but had learned through Greta and the others that understanding required humility, patience, and willingness to witness suffering without trying to fix it too quickly.

The story became part of military medical training, a case study in trauma recovery, in the importance of peer support, and how healing requires addressing both physical and psychological wounds simultaneously.

Future doctors and nurses learned about Camp Swift, about the shower facility where women had chosen vulnerability, about the ways compassion could cross enemy lines and create connection.

Despite propaganda s insistence that such connection was impossible.

In Stogart, at the school where Greta taught, there’s a small plaque commemorating her service.

It mentions her survival, her teaching, her commitment to helping others process trauma, but it doesn’t mention the scars, doesn’t describe the detention or the systematic cruelty or the long difficult path toward recovery.

Anna objected to this omission when the plaque was installed.

She argued that erasing the damage was another form of shame, another way of suggesting that survival should look unmarked, that healing means forgetting rather than integrating.

But the school administrators disagreed, wanting to honor Grea’s work rather than her suffering, wanting to emphasize what she’d built rather than what had been done to her.

Years later, Anna would understand both positions.

The desire to be known for achievements rather than victimization and the importance of acknowledging that achievements are often built on foundations of survived trauma.

Greta had been both things simultaneously.

A survivor of systematic cruelty and a teacher who debuilt meaningful life despite permanent damage.

Both truths mattered.

Both deserved remembering.

The scars had been real.

The survival had been real.

The recovery, partial and imperfect, had been real.

And the moment in a Texas shower facility when 16 women chose visibility over hiding, that had been real, too.

A moment of transformation that proved humanity could persist even after institutions tried to extinguish it.

The water still runs.

Somewhere in facilities across the world, people are learning that damage doesn’t have to mean destruction.

That scars can be evidence of survival rather than proof of defeat.

That choosing to be seen by those who understand can transform shame into testimony.

The story continues.

It always does.