April 1945, a dusty prison camp in Louisiana.

63 German women stepped off military trucks.

Their hands were shaking.

Their hearts were pounding.

They had heard the stories.

American captives were cruel.

American prisons were death camps.

Their own leaders had promised them capture meant suffering.

They expected beatings.

They expected starvation.

They expected revenge.

what they got instead, a plate of hot food.

But here’s the strange part.

When they took their first bite, they didn’t smile.

They didn’t say thank you.

Instead, one woman grabbed her water cup and drank it empty in seconds.

Another looked at the guard with wide eyes and asked, “Are you trying to poison us?” The American guard just laughed because on that plate sat something these German women had never seen before.

something so salty, so strange, so completely foreign that it made them question everything they knew about their enemy.

It was called corned beef and it was about to change how they saw America forever.

But what happened next? So that’s where this story gets really interesting.

Stay with me until the end because this isn’t just about food.

This is about war, lies, and the moment when enemy becomes human.

If you love stories like this, hit that subscribe button right now.

Like this video, support the channel, and let’s dive into one of the strangest food stories of World War II.

It all started when the truck stopped and the gates opened.

They arrived expecting the worst.

The truck stopped outside a converted factory building in Louisiana.

Spring got 1945.

The war in Europe was collapsing.

Germany was losing.

And these 63 women knew what losing meant.

They had heard the stories.

Enemy prisoners were beaten, starved, humiliated, left to rot in cages like animals.

Their own officers had warned them.

Nazi propaganda had promised them.

Americans were barbarians.

Capture meant death or something worse.

So when the truck doors open, the German women braced themselves.

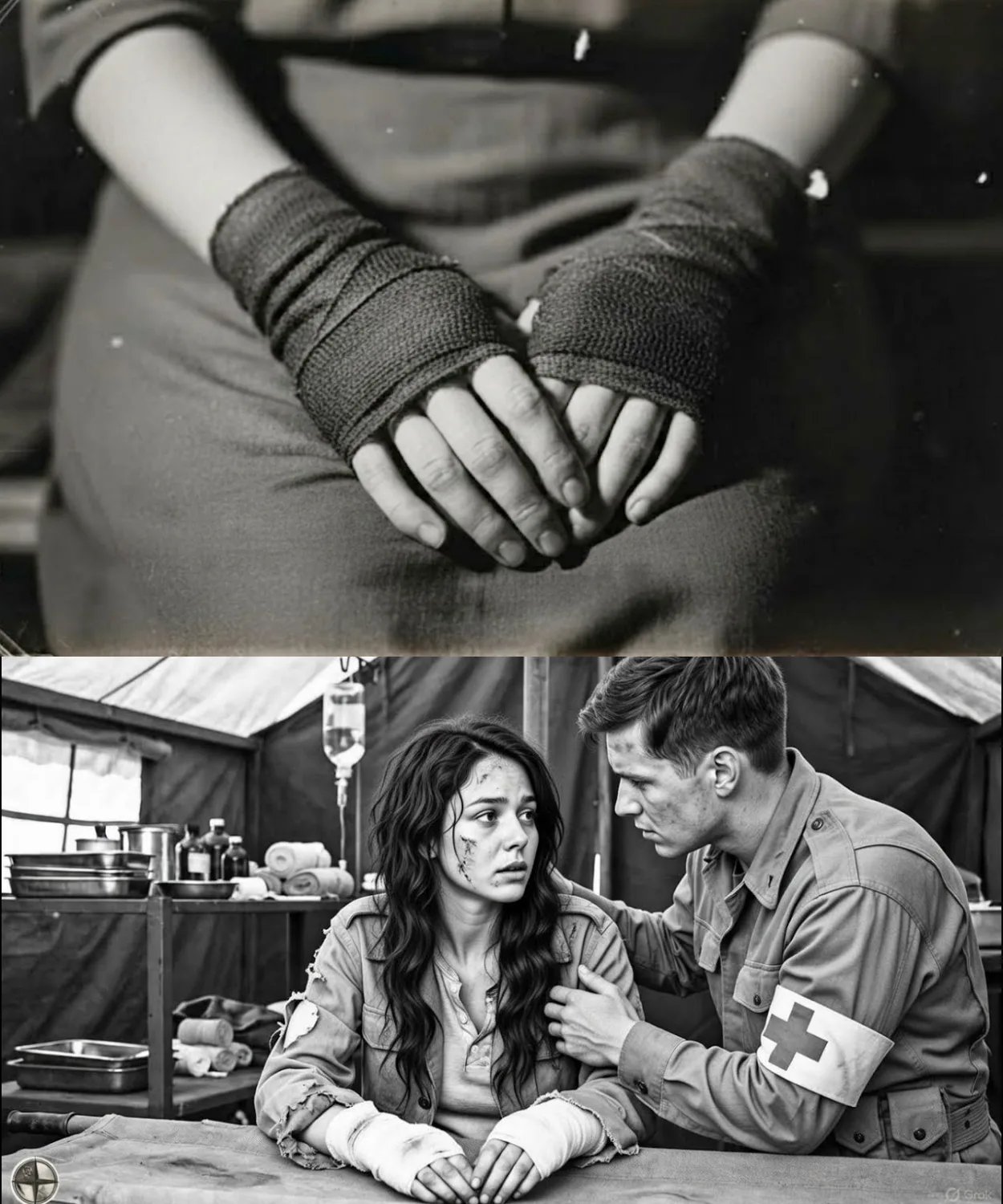

They were nurses, radio operators, signal core workers, vermacked auxiliaries who had served behind front lines.

Most were in their 20s.

Some were younger.

A few were barely 18.

They had never fired a weapon.

They had never killed anyone, but they wore German uniforms.

And now they belonged to the enemy.

Guards led them through iron gates, their boots echoed on concrete, their eyes scanned for signs of danger.

barbed wire, guard towers, attack dogs.

They found all three.

But something else was there, too.

The smell.

It hit them before they reached the messole.

Warm, heavy, salty, almost like seawater mixed with cooked meat.

One woman later described it as the strangest smell I had ever encountered indoors.

They didn’t know it yet, but that smell was American corned beef, and it was about to confuse them more than any battlefield ever had.

Inside the processing area, American soldiers handed them blankets, clean blankets, then soap, real soap, then a small towel, a toothbrush, and a comb.

The women looked at each other.

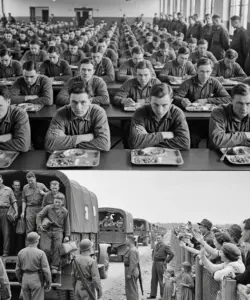

Was this a trick? According to US Army records, American P camps processed over 425,000 German prisoners by the end of 1945.

The system was massive, industrial organized, and the rules were clear.

Prisoners received the same base rations as American enlisted soldiers, the same food, the same portions, the same meals.

This was not special treatment.

This was standard policy.

But to the German women walking through those gates, it felt impossible.

One former signal operator, Ingred Müller, later recalled the moment in a 1987 interview.

We kept waiting for the real treatment to begin, she said.

We thought the kindness was a trick, a way to weaken us before the punishment started.

But the punishment never came.

Instead, the guards pointed them toward the mess hall.

Dinner was ready.

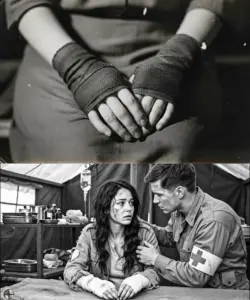

The building was large and plain.

Metal tables, wooden benches, American cooks in white aprons stood behind a serving line.

Steam rose from large pots, trays clinkedked, forks scraped.

It looked like any military cafeteria.

Nothing threatening, nothing cruel.

But for women raised under Nazi rule, the scene made no sense.

Enemies were supposed to hate you.

Captives were supposed to hurt you.

Yet here they stood, being handed food like guests at a strange family dinner.

The trays came out.

On each one sat a thick slice of something pinkish red, glistening with fat.

Beside it, pale green cabbage, a scoop of mashed potatoes, a piece of bread.

The meat looked wet, shiny, almost too pink.

Several women hesitated.

A few whispered among themselves.

One asked a guard, pointing at the meat, “Was this? What is this?” The guard shrugged.

“Corned beef.” The words meant nothing to them.

“Corn beef didn’t exist in Germany.

Not like this.

Not salted in brine for weeks.

Not served this way.” They sat down slowly, forks lifted, eyes studied the strange meat.

And in that silence, caught between fear, hunger, and confusion, the first bites began.

What happened next would stay with these women for the rest of their lives.

Not because of cruelty, but because of the complete absence of it.

Because the real shock wasn’t the taste of the meat.

It was the realization that everything they had been told about Americans might be wrong.

To understand why corned beef shocked these women, you must first understand where they came from.

Germany had a long history with preserved meat, but it looked nothing like what Americans ate.

In German kitchens, meat was smoked.

It was air dried.

It was ground into sausages with careful blends of spices.

Families passed down recipes for generations.

A grandmother’s worst recipe was sacred.

A butcher’s smoking technique was his livelihood.

German preservation was an art.

Slow, deliberate, regional.

Every part of the country had its own specialty.

Bavaria had its vice versa had its brat.

The Black Forest had its famous smoked ham.

These were not just foods.

They were identities.

And salt, yes, Germans used salt, but never like this.

American corned beef came from a completely different tradition.

It was invented out of necessity, not culture.

In the 1800s, Irish immigrants in New York needed cheap meat that lasted.

Jewish butchers in Manhattan sold them beef brisket, and the Irish preserved it the only way they knew, packed in massive amounts of coarse salt.

The word corned didn’t mean corn, the grain.

It meant the large corns or kernels of rock salt used in the brining process.

The meat sat in salty water for weeks, sometimes a month.

The salt killed bacteria.

It changed the texture.

It turned the beef pink.

By World War II, corn beef had become a staple of American military food.

It was cheap.

It lasted forever.

It could be shipped across oceans without spoiling.

The US Army purchased over 2.5 billion pounds of canned and processed meat.

During the war, corned beef was a significant part of that number.

Soldiers ate it in trenches.

Sailors ate it on ships.

And now, prisoners ate it in camps.

But for German women who grew up eating delicate smoked pork and mild herbed sausages, corn beef was an alien substance.

One prisoner, Hild Debrandt, a nurse captured near the rine, later wrote in her memoir about her first encounter with the meat.

It was so salty that my lips burned, she recalled.

I thought the Americans were trying to poison us slowly.

I could not understand why anyone would eat this by choice.

She wasn’t alone in her confusion.

Many German PS, both men and women, reacted the same way.

The salt content was overwhelming.

The texture was strange.

The pink color looked almost unnatural.

Some prisoners genuinely believed the meat had gone bad.

In German cooking, pink meat usually meant undercooked meat, dangerous meat.

Yet here, the Americans were serving it proudly as if it were a gift.

The taste clash went deeper than preference.

It was cultural, psychological, almost philosophical.

Germans believed food should be crafted with care.

Each ingredient had a purpose.

Each flavor was balanced.

Meals were expressions of discipline and tradition.

Americans, by contrast, prioritized practicality.

Food needed to travel.

It needed to last.

It needed to feed thousands quickly.

Taste was secondary to function.

Neither approach was wrong.

But when they collided in that Louisiana mess hall, the result was pure confusion.

One American cook stationed at Camp Rustin later described the scene to a military historian.

Those German gals looked at the corn beef like we had just served them boiled shoes, he said with a laugh.

We kept telling them it was normal.

They kept looking at us like we were crazy.

And perhaps from their perspective, the Americans were crazy.

After all, who would willingly soak good beef in salt water for 30 days? Who would boil it until it turned pink? Who would serve it proudly as if it were a fine meal? The answer was simple.

Americans would.

Because in America, this was fine dining for a soldier.

It was comfort food.

It was home.

But for those 63 German women, it was something else entirely.

It was proof that they had landed in a country they did not understand, a country that ate food they could not recognize, a country that treated prisoners in ways that made no sense, and dinner was only just beginning.

The messaul fell quiet.

Metal trays sat on wooden tables.

Steam rose from the food, forks rested in uncertain hands, and 63 pairs of eyes stared at the strange pink meat in front of them.

This was the moment, the first real bite.

Outside, Louisiana humidity pressed against the windows.

Inside, the air smelled thick with salt and boiled cabbage.

Ceiling fans turned slowly, pushing the warm air in lazy circles.

Somewhere in the kitchen, pots clanged.

A cook shouted something in English.

The German women understood none of it.

They only understood hunger and fear and the confusing meal before them.

One woman lifted her fork first.

Her name was Elsa Richter.

She was 24, a former telephone operator from Dresdon.

She had survived Allied bombing raids that killed thousands.

She had seen her city burn.

And now she sat in an American prison camp, staring at a slice of wet, salty meat.

She cut a small piece.

As she raised it to her mouth, she chewed.

Her face changed immediately.

Her eyes widened.

Her jaw slowed.

She reached for her water cup and drank half of it in one gulp.

“Ming got,” she whispered.

“My God.” The women around her watched.

Some leaned forward.

Others leaned back.

A few put down their forks entirely, but hunger was stronger than suspicion.

One by one, they began to eat.

The reactions were immediate and varied.

Some coughed, some grimaced.

A few pushed their trays away entirely.

One young woman, barely 19, started laughing.

A nervous, confused laugh that spread down the table like a wave.

An American guard standing nearby watched the scene with amusement.

He had seen this before with male prisoners.

But somehow watching these women react felt different, more human, less like processing enemies and more like hosting confused guests at a very strange dinner party.

According to camp records, the standard P ration included approximately 3,300 calories per day.

This was the same amount given to American soldiers in non-combat roles.

It included meat, vegetables, bread, and sometimes dessert.

By military standards, it was generous.

By German standards, it was unbelievable.

Back home, civilians were starving.

Ration cards limited families to tiny portions of meat per week.

Bread was mixed with sawdust.

Children went hungry.

Old people died from malnutrition.

And here in an enemy prison, German women were being served more food than their own families could dream of.

The paradox was almost too heavy to swallow, heavier even than the salt.

One prisoner, Margaret Vogle, later described the moment in a letter to her sister after the war.

“The meat was terrible,” she wrote.

“So salty I thought my tongue would crack.

But I ate every bite.

Because I did not know when food would come again.

I did not trust them yet.

That distrust was everywhere.

It hung in the air like the steam from the cabbage.

Every kindness felt like a trap.

Every full plate felt like a lie.

Some women ate fast, protecting their trays with their arms, old habits from scarcity.

Others ate slowly, watching the guards, waiting for the trick to reveal itself.

But the trick never came.

The guards didn’t laugh at them.

The cooks didn’t mock them.

The food, strange as it was, kept coming.

One cook, a large man from Texas named Harold Brennan, walked through the messaul offering seconds.

“More?” he asked, gesturing at the corned beef.

Most women shook their heads.

A few held out their trays.

Brennan later told an interviewer.

“This ladies were scared of everything.

scared of the food, scared of us, scared of what came next.

You could see it in their eyes.

All I could do was keep serving and hope they figured out we weren’t going to hurt them.

By the end of the meal, trays were mostly empty.

Not because the food tasted good, but because these women had learned long ago that you never waste a meal.

Still, as they filed out of the mess hall, one question lingered in every mind.

Why were the Americans being so kind? and what would they want in return? The complaints came quickly.

Within days, American cooks noticed a pattern.

German women ate almost everything on their trays.

The potatoes disappeared.

The bread vanished.

The cabbage was tolerated.

But the corned beef, half of it came back uneaten.

Trays returned to the kitchen with pink slices barely touched.

Sometimes just one bite was missing.

Sometimes the meat was pushed to the side, hidden under cabbage like evidence of a small crime.

The cooks talked among themselves.

What was wrong with these women? Didn’t they like meat? Sergeant Harold Brennan brought the issue to his supervisor.

They’re not eating the beef, he reported.

They drink all their water.

They ask for more bread, but they leave the meat.

The supervisor shrugged.

It’s good meat, same as we eat.

And that was true.

The corned beef served to German PSWs was identical to what American soldiers received.

Same recipe, same salt content, same preparation.

There was no difference, but difference wasn’t the problem.

Taste was.

Camp records from 1945 show that food waste was tracked carefully.

The military hated waste.

Every uneaten ounce meant wasted money, wasted shipping, wasted effort.

So when patterns emerged, cooks were expected to adapt and adapt they did.

First they reduced the salt in the cabbage.

German women had complained that everything tasted like the ocean by making the vegetables milder.

The overall meal became more bearable.

Next they increased the bread portion.

Bread was familiar.

Bread was safe.

German PS ate bread eagerly using it to fill their stomachs when other foods seemed too foreign.

Then came the potatoes.

Extra scoops appeared on trays.

Mashed potatoes helped absorb the salt from the beef, making each bite less intense.

Finally, someone introduced mustard.

It was a small thing.

A yellow squeeze bottle placed on each table.

But it changed everything.

German women knew mustard.

German mustard was famous.

Sharp, tangy, perfect with sausages.

American mustard was sweeter, milder, almost like a source, but it was familiar enough to feel like home.

One prisoner, Ursula Kra, later recalled the discovery in an interview.

A woman at my table put mustard on the salty meat, she said.

I watched her eat it without making a face, so I tried it, too.

The mustard helped.

It covered some of the salt.

After that, I always used mustard.

Word spread quickly through the barracks.

Mustard helps, bread helps, potatoes help.

Slowly, the women developed strategies to survive corned beef day.

They weren’t enjoying the food, but they were managing it.

American cooks noticed the change.

Trays started coming back empty.

The pink slices disappeared along with everything else.

Brennan smiled when he saw it.

They’re figuring it out, he told his team.

Give them time.

Time was something these women had plenty of.

Days turned into weeks.

Weeks turned into months.

The war in Europe ended.

Germany surrendered.

But the women remained in Louisiana, waiting for repatriation paperwork, waiting for ships, waiting for a country that no longer existed as they remembered it.

And during that waiting, something unexpected happened.

The food started to feel normal.

Corned beef still tasted salty.

It still looked strange, but it no longer shocked them.

It became routine, expected, even reliable.

One woman, Bridget Stein, wrote in her diary during this period, Tuesday means corned beef.

She noted, “I do not love it, but I eat it.

I am grateful for it.” At home, my mother is eating grass soup.

Here, I am eating meat.

Real meat.

I have no right to complain.

That perspective shifted everything.

Complaints faded.

Suspicion softened.

The women stopped expecting cruelty and started accepting reality.

The Americans were not trying to poison them.

The Americans were not trying to punish them.

The Americans were simply feeding them the only way they knew how.

It wasn’t perfect.

It wasn’t German.

But it was enough.

And sometimes enough is the beginning of understanding.

The cooks kept serving.

The women kept eating.

And somewhere between the salt and the mustard, two cultures found a strange middle ground.

But the real surprise was still coming.

Nobody saw it coming.

8 weeks had passed since the German women first arrived at the camp.

8 weeks of adjustment, 8 weeks of learning, 8 weeks of slowly accepting that this strange American food would not kill them.

Then one Tuesday morning, the menu changed.

The cooks had received a shipment of canned ham.

It was a welcome break from routine.

Ham required less preparation.

It tasted milder.

It seemed like an easy win.

Lunch trays came out with thick slices of pink ham, green beans, and buttered rolls.

The cooks expected smiles.

They expected gratitude.

They expected the German women to celebrate the change.

Instead, they got questions.

One woman approached the serving line.

and her name was Leisel Hartman.

She was 31, a former Vermach secretary captured near Belgium.

She had been in the camp longer than most.

She spoke a little English now, broken, careful, but understandable.

She looked at the tray.

She looked at the cook.

Then she asked a question that made Harold Brennan stop midscoop.

Where is the salty meat? Brennan blinked.

What the salty meat? Leisel repeated.

The red meat.

Very salty.

Where is it? Brennan stared at her for a long moment.

Then he started laughing.

You mean corned beef? He asked.

Yes, corned beef.

When does it come back? Brennan shook his head in disbelief.

He turned to his fellow cooks.

Did you hear that? She wants the corned beef back.

The kitchen erupted in laughter, not cruel laughter.

Surprised laughter.

The kind of laughter that comes when the world stops making sense.

For weeks these women had complained.

They had grimaced.

They had pushed the meat aside.

They had called it salt blocks.

They had joked about turning into pickles.

And now they wanted it back.

Brennan wiped his hands on his apron.

Next Tuesday, he said.

Corn beef comes back next Tuesday.

Leisel nodded seriously.

Good.

We will wait.

She took her ham tray and walked away.

Behind her, other women were having similar conversations.

Several asked guards about the missing corned beef.

A few seemed genuinely disappointed.

Word spread through the camp within hours.

The German women missed the salty meat.

It became a story that guards repeated for years.

The same dish that once caused confusion was now being requested.

The same taste that once seemed like punishment was now expected, even wanted.

How did this happen? The answer was simpler than anyone imagined.

Humans adapt.

Taste adapts.

Comfort adapts.

Corned beef had become familiar.

It marked the calendar.

It signaled routine.

In a life with no control, no freedom, no certainty about the future.

That routine mattered more than flavor.

One prisoner Gertrude went explained it years later in a German documentary.

We did not love the taste, she said, but we loved knowing what to expect.

Corned beef meant Tuesday.

Tuesday meant another week survived.

It gave us something to hold on to.

There was another reason, too.

A deeper one.

The women had finally accepted that Americans were not their enemies.

Not really.

The guards joked with them.

The cooks tried to help them.

The food kept coming day after day without cruelty or conditions.

Corned beef was part of that realization.

If Americans ate this same salty meat willingly, then maybe Americans were not monsters.

Maybe they were just people with different tastes, different traditions, different ways of preserving food.

And if Americans were just people, then maybe the war had been built on lies.

That thought was dangerous.

It shook everything these women had believed.

But the evidence sat on their trays every Tuesday.

pink, salty, undeniable.

When corned beef returned the following week, something had changed in the mess hall.

Women ate without complaining.

A few even smiled as they chewed.

One woman raised her water cup toward Brennan in a small toast.

He didn’t understand the gesture, but he nodded back.

Somewhere between suspicion and acceptance, a wall had fallen.

Not a political wall, not a military wall, just a small human wall knocked down by salt and bread and time.

And that perhaps was the strangest victory of all.

The war ended, the camps emptied, the women went home, but home was not what they remembered.

Germany in 1946 was a nation of ruins.

Cities lay flattened.

Factories stood silent.

Families searched for missing relatives.

Food was scarcer than ever.

The average German civilian survived on fewer than 1/500 calories per day.

Many survived on less.

The women who returned from American captivity carried something unexpected with them.

Not anger, not hatred, not stories of torture or abuse.

They carried confusion and gratitude and memories of salty meat.

One former prisoner, Ingred Müller, arrived in Hamburg to find her childhood home destroyed.

Her mother was dead.

Her brother was missing.

She had nothing left except the clothes she wore and the memories she carried.

“Years later,” she told an interviewer something remarkable.

“When I was starving in Hamburg, I thought about that American messaul,” she said.

“I thought about the corned beef I once hated.

I would have given anything for one slice.

Just one slice of that salty meat I used to push away.” Her story was not unique.

Across Germany, returning PSWs told similar tales.

They described American camps with disbelief, full meals, clean blankets, medical care, fair treatment.

Many Germans refused to believe them.

The stories sounded like propaganda, like lies designed to make Americans look good, but they were true.

According to postwar records, the mortality rate in American P camps was less than 1%.

Compare that to Soviet camps where up to 30% of German prisoners died from starvation, disease, and execution.

American captivity was not pleasant, but it was survivable.

Often, it was more than survivable.

The food was a symbol of something larger.

American abundance was real.

It was not a trick.

It was not a bribe.

It was simply how Americans lived.

They had more food than they needed.

They shared it even with enemies.

They served corned beef because corned beef was what they ate.

For women raised under Nazi ideology, this was impossible to understand at first.

They had been taught that Americans were weak, decadent, morally corrupt.

The propaganda painted a picture of lazy capitalists who would crumble under pressure.

Instead, these women found a nation so wealthy that even its prisoners ate better than German civilians.

A nation so organized that it could feed hundreds of thousands of captured enemies without complaint.

A nation that treated women’s soldiers with basic dignity instead of revenge.

The contradiction shattered something inside them.

Margaret Vogle, the woman who once wrote about her cracked tongue from too much salt, later became a school teacher in West Germany.

She taught history to teenagers and she always included one lesson that surprised her students.

I tell them about the corned beef, she said in a 1978 interview.

I tell them how I hated it, how I feared it, how I eventually missed it, and I tell them what it taught me.

That enemies are not always what you expect, that kindness can come from strange places, that a meal can change how you see the world.

Her students often laughed at the story.

Salty meat.

That was her big lesson.

But Margaret understood something they did not.

She understood that wars end not just with treaties, but with small human moments.

A cook offering seconds.

A guard nodding at a toast, a plate of food that said without words, “You are still a human being.” The German women who passed through American P camps carried those moments forever.

They passed them to their children.

They whispered them to grandchildren.

They wrote them in memoirs that historians still study today.

And at the center of many stories sat one humble dish.

Pink, salty, strange, unforgettable.

Corned beef was never about taste.

It was about what happens when propaganda meets reality.

When fear meets kindness, when enemies discover that the other side is also human.

The women came as prisoners.

They left as witnesses.

and their testimony echoed for generation.

In the end, America’s greatest weapon was not its bombs, its planes, or its army.

It was a steaming plate of salty meat served without hatred to women who expected none.

History remembers battles.

It remembers generals and treaties and surrender ceremony.

But sometimes the truest history happens in messole in small moments between strangers in the taste of unfamiliar food that slowly becomes familiar.

The German women who first tried American corned beef did not know they were part of something larger.

They only knew they were hungry, scared, and far from home.

What they discovered changed them forever.

Not the salt, not the pink meat, but the simple act of being fed by an enemy who chose not to act like.

That is the lesson of this story.

That humanity survives even in war.

That meals can carry meaning.

And that sometimes the strangest food teaches the deepest truth.

Mississippi 1943.

Major General Hinrich von Closen stood in the processing office at Camp Clinton.

His uniform still bearing the insignia of high command, his posture rigid with the expectation of respect that rank demanded.

He addressed Brigadier General William Bradford in precise English.

I require separate quarters, orderly service, and exemption from manual labor per my status as general officer.

Bradford looked at him for a long moment, then gestured toward the kitchen, visible through the window, where enlisted prisoners peeled potatoes in long rows.

You’ll start tomorrow morning, 0600.

Bring gloves if your hands are soft.

What happened next would become legendary in P camp administration.

The autumn sun beat down on central Mississippi, turning the air thick and heavy, making even breathing feel like work.

Camp Clinton sprawled across former farmland, a prisoner of war facility holding 15,000 German soldiers captured in North Africa and Sicily men who de expected quick victory and instead found themselves on ships crossing the Atlantic toward detention in a country most had never imagined visiting.

Major General Hinrich von Clawson had arrived in late September 1943 among a transport of high-ranking officers being consolidated at facilities with appropriate security.

He was 52 years old, Prussian aristocracy, career military officer who decommanded division level operations in North Africa until captured during the chaotic final weeks of the Africa corpse collapse.

He carried himself with the bearing of someone accustomed to deference to orderlys managing his needs to enlisted men executing his requirements without question.

The Geneva Convention specified that officer prisoners could not be compelled to work that they should receive treatment appropriate to their rank, that military hierarchy should be preserved even in detention.

Von Clausen understood these provisions intimately, had studied them as part of his military education, knew his rights, and intended to exercise them fully.

Brigadier General William Bradford, commanded Camp Clinton.

He was 48 from Tennessee, had been a National Guard officer called to active duty who droven capable enough to be assigned P administration rather than combat command.

He ran his facility by the book Geneva Conventions, observed scrupulously, prisoners treated fairly but firmly, security maintained without cruelty, but also without sentiment that might compromise order.

When Vanclausen presented his demands for special treatment, Bradford listened without interruption.

Separate quarters away from enlisted prisoners, an orderly to manage his personal needs, exemption from all work assignments, access to better food rations befitting officer status, permission to wear his full uniform with insignia rather than the standard prisoner clothing.

The requests weren’t technically unreasonable under Geneva Convention interpretations that prevailed in some facilities.

Many P camps did segregate officers, did provide certain privileges, did maintain military hierarchies that mirrored the structures prisoners had known before capture.

But Bradford had developed different philosophy through 18 months of managing Camp Clinton.

He’d observed that segregating officers often reinforced arrogance, that special treatment bred resentment among enlisted prisoners, that maintaining rigid hierarchies prevented the kind of attitude adjustment that made reintegration possible after the war ended.

General von Clausen, Bradford said in his slow Tennessee draw, choosing words carefully.

The Geneva Conventions say I can’t make you work.

They don’t say I have to give you special accommodations beyond basic humane treatment.

You’ll share barracks with other officers, not enlisted men.

That much I’ll grant.

But you’ll eat same food, follow same schedules, and participate in same daily routines as every other prisoner in this camp.

Von Clausin’s face flushed with anger and indignation.

This is unacceptable.

My rank entitles me to treatment befitting a general officer.

I demand to speak with your superior to lodge formal protest through proper channels.

You’re welcome to file complaints,” Bradford replied evenly.

“But while those complaints work their way through channels, you’ll live under the rules I just explained.

Starting tomorrow at 0600, you’ll report to the kitchen for work detail.

We need potatoes peeled for 15,000 men.

Your hands will be useful.

I am general officer.

I do not peel potatoes.

You’re a prisoner of war who happens to have been a general.

Here, everyone contributes.

You want special treatment? Earn it through behavior, through setting example, through showing your fellow prisoners what honorable leadership looks like.

But you don’t get privileges just because you used to give orders to other people.

The confrontation became immediate test of wills.

Von Clausen refused to report for kitchen duty the next morning, remained in his monk, waited for guards to acknowledge the absurdity of expecting a general officer to perform menial labor alongside common soldiers.

Bradford was informed of the refusal by .

By he was standing beside von Clausson’s monk, his expression showing neither anger nor particular concern, just the steady patience of someone who de dealt with resistant prisoners before and understood that time was on his side.

General, Bradford said, the title carrying slight ironic emphasis.

You have two choices.

You can come to the kitchen voluntarily and participate in the work that every able-bodied prisoner in this camp performs.

Or you can remain here, in which case you’ll receive no meals today, no recreation privileges, no access to the camp library or other amenities.

Tomorrow, same choice.

and the day after.

You can be stubborn as long as you want, but you’ll get hungry eventually, and when you do, you’ll peel potatoes like everyone else.” Von Clawson stared at the ceiling, his jaw clenched, his body rigid with fury that circumstances had reduced him to this being, ordered around by an American general who probably hadn’t even commanded in actual combat, who clearly didn’t understand proper military hierarchy, who was violating every principle of how captured officers should be treated.

But he was also 52 years old.

His body already showing the effects of months of inadequate nutrition during the Africa corpse final campaigns and the long transport to America.

Hunger was not abstract concept.

It was immediate physical increasingly urgent as the day wore on without breakfast, without lunch.

As evening approached, and dinner smells wafted from the mess hall, while he lay in his bunk, maintaining pointless resistance, by the third day he capitulated, he rose before dawn, dressed in the standard prisoner work clothing, walked to the kitchen with the bearing of a man approaching his own punishment, and stood before the massive pile of potatoes that needed processing for the day’s meals.

The kitchen supervisor, a sergeant named Thomas Webb, who’d worked in restaurant kitchens before the war, handed him a peeler and a bucket.

Around him, dozens of other prisoners enlisted men, junior officers, a few NCOs worked in steady rhythm, their hands moving automatically through the repetitive task, their conversations quiet but present, creating the ambient social noise that accompanies group labor.

You’ll want to get a rhythm going,” Web said, demonstrating the efficient motion that minimized wasted energy.

“Try to keep the peels thin.

We’re not trying to waste good potato.” “And watch your fingers, especially if you’re not used to this kind of work.” Von Clausen took a potato, began peeling with movements that were slow, awkward, inefficient.

His hands, accustomed to signing orders and reviewing maps, and all the abstract work of high command, struggled with the simple physical task that enlisted men executed without thought.

Other prisoners watched covertly, aware that a general officer was performing labor that military tradition reserved for lowest ranks, that the American camp commander had somehow compelled this reversal of natural order.

Their reactions varied.

Some showed satisfaction at seeing aristocratic officer reduced to their level.

Others felt uncomfortable with this violation of military hierarchy they’d internalized.

A few wondered if this meant Americans truly didn’t respect proper distinctions between ranks and classes.

Over the following weeks, von Clausen continued reporting for kitchen duty, not because he’d accepted the legitimacy of Bradford’s approach, but because hunger proved stronger than pride.

Because isolation without privileges made resistance unbearable.

Because pragmatism eventually overcame ideology when facing daily choice between capitulation and suffering.

But something unexpected began happening during those hours peeling potatoes.

Von Clawson found himself adjacent to enlisted prisoners he never have encountered in Germany.

s rigid military hierarchy, hearing their conversations, learning their perspectives, beginning to understand the war from viewpoints that had been invisible when he’d occupied positions of command.

Corporal France Vber worked beside him most mornings a farmer from Bavaria who he been drafted in 1940 and had spent three years following orders without understanding why fighting in places he’d never wanted to visit surviving through luck rather than ideology.

He talked while working his voice carrying the particular resignation of someone who d stopped believing official narratives but lacked alternatives to replace them with.

You know what’s strange? Hair General Vber said one morning, his hands moving automatically through potato after potato.

Before the war, I grew potatoes, fed my family, sold surplus at market, did honest work that hurt no one.

Then they put me in uniform, gave me rifle, sent me to Africa to take land that belonged to other people.

And now I’m back to potatoes that is prisoner in America.

Peeling food I’ll eat but didn’t grow.

The circle seems pointless when you see it whole.

Von Clausen didn’t respond immediately.

Uncertain how to engage with such direct questioning of the war’s purpose.

Such naked admission that military service might have been waste rather than noble duty.

In Germany’s military culture, junior ranks didn’t speak to generals this way.

didn’t express doubt or philosophical musings that suggested questioning of official objectives.

“War has purposes beyond individual understanding,” Vonclawson finally said, offering the standard formulation he’d given subordinates who’d expressed doubts.

“Soldiers serve larger strategies, trust leadership to pursue national interests that may not be apparent at tactical levels.” Vber nodded, but his expression showed skepticism.

Maybe or maybe we all just followed orders because questioning was dangerous because entire system was designed to prevent thinking about whether the orders made sense.

Here peeling potatoes, no one watching us carefully.

No punishment for speaking honestly.

I can finally say what I thought but could in voice.

I think we fought for nothing.

Died for nothing achieved.

Nothing except destroying our country and others.

The words hung in the air between them, dangerous and honest, articulating what many prisoners were beginning to think, but few had dared to say openly, especially to officer who represented the hierarchy that had commanded their service.

Bradford observed vonleness s adjustment through reports from guards and through his own periodic visits to the kitchen.

He saw the general’s efficiency improving, saw him beginning to engage in conversation with other prisoners, saw the rigid hotel gradually eroding under the leveling effect of shared labor and informal social interaction that work environments create.

In November, Bradford called von Clausen to his office for the first time since their initial confrontation.

The German officer entered expecting confrontation or additional humiliation.

His defenses raised, his bearings stiff with residual resentment.

But Bradford’s demeanor was cordial rather than adversarial.

He offered coffee, gestured to a chair, waited until Von Clausen was seated before beginning what was clearly intended as conversation rather than discipline.

“I’ve been hearing good things about your work,” Bradford said.

The kitchen supervisor says you’re reliable, that you’ve learned the tasks, that you don’t complain or resist anymore.

That’s progress.

Vanclausen absorbed this, uncertain whether he was being mocked or genuinely praised.

Whether this was American general, recognizing his compliance or setting up further degradation.

I had no choice, he finally said, his English formal and precise.

You made continued resistance impractical.

I adapted to circumstances I could not change.

That’s fair, Bradford acknowledged.

But I want you to understand why I insisted on this approach.

It wasn’t personal vendetta or desire to humiliate you.

It was strategic decision about what kind of men I wanted walking out of this camp when the war ends.

He leaned forward, his expression serious.

I can run this camp three ways.

I can maintain rigid military hierarchy, give you private quarters and orderlys, and all the privileges you think your rank deserves.

I can treat you all exactly the same, no distinction between officers and enlisted.

Or I can use flexible approach where privileges are earned through behavior rather than automatically granted based on past positions.

I chose the third option.

For what purpose? Because I’m not just holding you until war ends.

I am trying to help you become men who can rebuild Germany into something better than what you left.

And that requires questioning the hierarchies that made the war possible.

Recognizing that obedience to authority isn’t virtue when authority is corrupt.

Learning to see other humans as equals rather than as superiors or subordinates in some rigid chain of command.

Vanclausen listened, his face showing the conflict between indignation at being lectured by enemy officer and intellectual engagement with ideas that challenged comfortable assumptions.

You think peeling potatoes teaches such lessons? I think peeling potatoes alongside men you used to command teaches humility.

I think working together without rank barriers shows you that common soldiers have intelligence and dignity you might have missed when you are just giving them orders.

I think experiencing what it s like to be treated as equal rather than as superior changes perspective in ways that lectures and reading never could.

By December von Clausen had been integrated into regular Kev life in ways that would have seemed impossible 3 months earlier.

He still lived in officer barracks, still had certain technical privileges that Geneva Conventions granted, but he worked alongside enlisted prisoners, ate at the same tables, participated in recreation activities without expecting special difference.

And he was changing, not dramatically, not with sudden conversion or complete abandonment of his previous worldview, but gradually, almost imperceptibly, the rigid aristocrat who demanded privileges was being replaced by someone more thoughtful, more questioning, more willing to examine assumptions that had once seemed inviable.

He began attending camp discussion groups voluntary gatherings where prisoners could examine political and philosophical questions where chaplain and education officers facilitated conversations about what had happened to Germany, what might come next, how men who’d fought for a failed cause might rebuild their nation after defeat.

In one session in January 1944, the topic was leadership and obedience.

A chaplain named Robert Hayes posed questions designed to provoke thinking rather than to elicit correct answers.

When is obedience a virtue and when is it moral failure? How do individuals maintain ethical judgment while serving in hierarchical institutions? What obligations do leaders have beyond following orders from their own superiors? Van Clausen found himself speaking, his voice carrying both his command experience and his newer uncertainty.

I believe that good soldiers follow orders, that military hierarchy exists to enable coordination, that questioning authority during wartime is dangerous indulgence.

But here, working alongside men I once commanded, hearing their perspectives, seeing the war through their eyes, I begin to wonder if my obedience was virtue or if it was moral cowardice, if I should have questioned orders that, in retrospect seem wrong, if leadership means more than just efficient execution of superiors intentions.

Another officer responded, “Older, more ideologically committed.

But without obedience, military forces collapse into chaos.

How can armies function if every soldier questions every order? Perhaps armies that require blind obedience shouldn’t function.

Von Clausen heard himself say, surprised by his own words, by how far his thinking had traveled from the certainties he’d carried into captivity.

Perhaps men should be able to distinguish legitimate military objectives from immoral commands.

Should be encouraged to question rather than punished for thinking.

American forces seemed to operate this way.

More discussion, more input from junior ranks, less rigid hierarchy, and they defeated us.

The observation hung in the air, provocative and undeniable.

the German military tradition that von Clawson had been raised in emphasized obedience as supreme virtue, questioning as weakness.

But that tradition had led to comprehensive defeat, had served leaders whose objectives proved catastrophic, had enabled atrocities because soldiers followed orders without moral evaluation.

In March 1944, Von Clausen’s mother died in Germany.

The news reached him through Red Cross channels, a telegram with minimal details, her age, the date, a brief statement that she’d been buried in the family plot.

No cause of death, no description of circumstances, just the bare fact that she was gone and he’d been unable to be present, unable to say goodbye, unable to fulfill the duties that sons owe to mothers.

He grieved privately, as was his custom, but Bradford heard about the loss through camp channels, and sought him out that evening.

He found von Clausen sitting alone outside the barracks, staring at the Mississippi sunset, his face showing the particular pain of loss compounded by powerlessness and distance.

“I heard about your mother,” Radford said, settling onto the bench beside him without asking permission.

“I’m sorry.

Losing a parent is hard, even when you’re present when you’re half a world away in enemy detention, unable to be there.

I can’t imagine how difficult that must be.

Vanclausen nodded, but didn’t speak immediately, his throat tight with emotion that Prussian training had taught him to suppress, but that grief made impossible to fully contain.

“She didn’t approve of my career,” he finally said, his voice quiet.

She wanted me to stay on the family estate, to manage the lands as my father had, to live quiet life raising crops and horses rather than commanding men in combat.

We argued when I chose military academy, barely spoke during my early career.

But as I rose in rank, earned recognition, she softened, began to take pride in her son, the general, began to brag to her friends about my service to the nation.

He paused, his hands clenched together.

Now that nation is destroyed, that service proven worthless, that pride shown to be misplaced, and she died without knowing whether I survived capture without final conversation, where I might have admitted she was right, that I should have chosen her path rather than the one that led here to sitting beside enemy general mourning losses.

That didn’t have to happen if men like me had questioned rather than obeyed.

Radford let the words settle before responding.

My father was a farmer, he said, wanted me to stay home too, to work the land, to continue family traditions.

I disappointed him by joining National Guard by seeking military career he considered waste of my capabilities.

He died in 1940 before this war, before I got command of this camp.

I think he would have been proud eventually if he’d lived to see what I’ve built here, but I’ll never know.

And that uncertainty stays with you.

The two men sat in companionable silence.

Enemy generals connected by shared experience of loss and regret and the universal human pattern of disappointing parents while pursuing paths that seemed necessary in the moment but questionable in retrospect.

By summer 1944, Vanclausen had become informal leader among German officers at Camp Clinton.

Not through formal appointment or American authorization, but through natural process by which capable people emerge as organizational nuclei when groups need coordination and representation.

But his leadership style had changed.

The autocratic approach he’d employed in military service had been replaced by something more consultative, more willing to listen, more focused on genuine consensus rather than just efficient compliance.

He organized work details fairly, represented prisoner concerns to American authorities, facilitated discussion groups where men could process their experiences and plan for uncertain futures.

Bradford observed this transformation with satisfaction that bordered on vindication.

His approach refusing special privileges requiring shared labor, forcing aristocratic officer to experience life as common prisoner had achieved exactly what he deoped.

Not breaking von Clawson’s spirit, but remolding his perspective.

Not humiliating him, but helping him discover that genuine leadership came from service rather than from rank.

In August, Bradford called von Closen to his office for conversation that had become almost routine two generals discussing camp operations, prisoner morale, plans for eventual repatriation that everyone knew was still years away.

I want to ask you something, Bradford said after they’d covered standard topics.

When you first arrived, if I’d given you everything you demanded, separate quarters, orderly service, exemption from work, what kind of man would you be now? Von Clausen considered the question seriously, his face showing the thoughtful expression that had replaced his initial hot.

I would be the same man who arrived, still believing that rank entitled me to difference, that hierarchies reflected natural order, that my position elevated me above common soldiers who existed to execute my commands.

I would have learned nothing, changed not at all, waited out my detention in comfortable isolation before returning to Germany unchanged, except for having survived.

And instead, instead I peeled potatoes with men I used to command.

I heard their stories, learned their perspectives, began to understand the war from viewpoints that were invisible when I occupied positions where junior ranks stood at attention, and never spoke honestly.

I was forced to question assumptions I’d held for decades, to examine whether the leadership I deprided myself on was actually worth anything if it served catastrophically bad objectives.

He paused, then added quietly.

You humiliated me, General Bradford.

But you also educated me in ways that comfort never could have.

Bradford nodded, moved by this admission from someone who’d been so resistant initially.

I didn’t do it to humiliate you.

I did it because I’ve seen what happens when officers get special treatment.

They maintain their old attitudes, reinforce their old certainties, learn nothing from defeat because they never have to confront it directly.

Whereas working alongside your own men, being treated as equal rather than as superior, that breaks down the barriers that prevent genuine learning.

Will other camps adopt your methods? Probably not.

Most commanders prefer easier approaches.

Either maintain strict hierarchies or treat everyone exactly the same.

My method requires judgment, requires knowing when to push and when to accommodate, requires believing that changing minds is more important than just containing bodies.

It’s more work than most people want to invest.

But it works.

Yes, it works.

You’re evidence of that.

Hinrich von Clausen remained at Camp Clinton until 1946 when repatriation finally began processing high-ranking officers back to occupied Germany.

He returned to find his family estate occupied by Russian forces.

His aristocratic title meaningless in the new political order.

His military career properly concluded by defeat and detention.

He settled in Hamburg, found work teaching at a school being established for orphaned and displaced children, applied his evolving understanding of leadership to education rather than to military command.

He taught history and ethics, emphasizing critical thinking over obedience, questioning over compliance, moral courage over efficient execution of orders that might be wrong.

In letters to Bradford that continued for decades, he reflected on his time at Camp Clinton, on the potato peeling that had seemed like cruel humiliation, but had proven to be transformative education.

You taught me through the simplest method by making me experience what my own soldiers experienced.

He wrote in 1950, “I had commanded men to perform labor I considered beneath me.

had expected difference based on rank rather than earning respect through character.

Your refusal to grant me special treatment forced me to discover that I had no inherent superiority, that rank was just social.

Construction that defeat had rendered meaningless, that genuine leadership required serving alongside those you lead rather than commanding.

From elevated position, he became advocate for military reform in West Germany, arguing that the new Bundesphere should break from Prussian traditions, should emphasize moral education alongside.

Tactical training should teach soldiers that obedience has limits that following orders, doesn’t absolve individuals from responsibility for their actions.

In 1963, he traveled to Mississippi to visit Bradford to see Camp Clinton, which had been converted to different purposes, but still existed as physical space where his transformation had occurred.

They toured the facility together.

Two old generals remembering the confrontation that had begun with Von Clausen demanding privileges and Bradford refusing them.

They visited the kitchen where Von Clausan had peeled potatoes.

now serving different purposes, but still recognizable.

He stood where he’d worked 20 years earlier, remembering the anger and humiliation, the gradual adjustment, the conversations with enlisted men that had challenged his assumptions about hierarchy and worth.

I hated you for months, Vonclen admitted, standing in that kitchen, his voice carrying both honesty and affection.

I thought you were cruel, vindictive, that you were violating Geneva Conventions and my rights as officer.

I filed formal complaints through Red Cross, demanded that other authorities override your decisions.

I was certain that when superiors reviewed your approach, they would order you to provide the special treatment I deserved.

And when they didn’t, Bradford asked, smiling, I began to wonder if perhaps I’d been wrong.

If perhaps special treatment wasn’t right, I deserved but was privileged.

ID been granted by system designed to preserve aristocratic power.

If perhaps your approach refusing privileges, requiring shared labor, treating me as equal rather than as superior, was more honest, more moral, more aligned with actual human dignity than the hierarchical system I’d taken for granted.

They left the kitchen, walked across the grounds where thousands of prisoners had once lived, where barracks had stood, and work details had formed each morning and evening formations and marked the days.

The physical evidence was mostly gone, but both men carried memories that made the space sacred in ways that monuments and plaques never could.

Bradford died in 1970.

his obituary noting his service at Camp Clinton, but not fully capturing the revolutionary approach he deaken to P management, the philosophy he developed about using detention as education rather than just as containment.

Von Clausen attended the funeral traveling from Germany to Tennessee, paying respects to the man who dee refused his demands and thereby given him something more valuable than special quarters and orderly.

Service and opportunity to discover that his rank had been social construction rather than reflection of inherent worth.

That his leadership had been incomplete because it had never required experiencing the conditions he deimposed on subordinates.

That genuine authority came from character rather than from position.

He spoke at the service, his English now fluent, his voice carrying emotion that Prussian training no longer suppressed.

General Bradford taught me leadership by refusing to treat me as leader.

He taught me humility by denying me privileges.

He taught me to question authority by exercising his authority to force me into situations where my assumptions were challenged daily.

These lessons came through potato peeling, through working alongside men I’d once commanded, through discovering that when rank was stripped away, I had no inherent superiority to justify the difference I’d expected.

This education was more valuable than any formal schooling I’d received, more profound than any lecture could have been, more lasting because it came through experience rather than through abstract instruction.

At Camp Clinton’s former site, now converted to industrial park, there’s a historical marker documenting the facility’s wartime role.

It mentions the 15,000 prisoners held there, the agricultural work they performed, the Geneva Convention compliance that characterized American P management.

But it doesn’t mention von Clausen and Bradford doesn’t tell the story of the German general who demanded special treatment and the American general who made him peeled potatoes instead doesn’t capture the particular revolution that occurred when aristocratic officer was forced to experience life as common prisoner and discovered through that experience that his assumptions about hierarchy and worth had been illusions supporting unjust systems.

That story survives in letters archived at military history collections.

In von Closen’s memoir published in German in 1965 in oral histories from prisoners who witnessed the confrontation and saw the gradual transformation it produced.

And it survives in the philosophy both men articulated in their later years.

That genuine leadership requires experiencing the conditions you impose on others.

That rank alone doesn’t justify special treatment.

that hierarchies should be questioned rather than automatically reinforced.

That the work of rebuilding after ideological collapse requires first breaking down the barriers that ideology created.

Von Clausen peeled potatoes at camp.

Clinton from September 1943 until his repetriation in 1946.

Thousands of potatoes, millions probably.

His hands developing calluses and efficiency.

His perspective shifting with each conversation overheard or participated in his worldview dissolving under the weight of daily experience that contradicted everything he debelieved about his place in social order.

Those potatoes nourished 15,000 prisoners through years of detention.

But they also nourished something less tangible.

The slow transformation of one man from arrogant general who demanded privileges into thoughtful educator who taught that obedience has limits, that hierarchy isn’t natural law, that defeat can become education if approached with humility rather than with defensive preservation of old certainties.

Bradford made van peel potatoes.

And in that simple insistence, in that refusal to grant special treatment based on former rank, in that steady application of principle, that all prisoners should contribute regardless of their previous positions, he facilitated transformation that proved more lasting than military victory, more profound than punishment, more valuable than any Geneva Convention privilege could have been.

The potatoes were peeled.

The war ended.

The prisoners went home.

But the lesson remained that sometimes the most revolutionary act is refusing to treat someone as special.

That sometimes genuine respect comes from demanding equality rather than granting difference.

That sometimes the path to wisdom runs through the kitchen where everyone has hands get dirty and everyone has work matters equally.

Regardless of who they used to be before circumstances stripped away their rank and left just the human beneath.