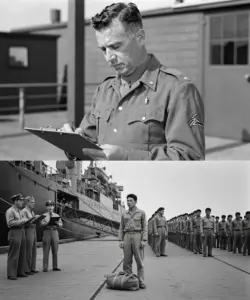

April 1945, Camp Gruber, Oklahoma.

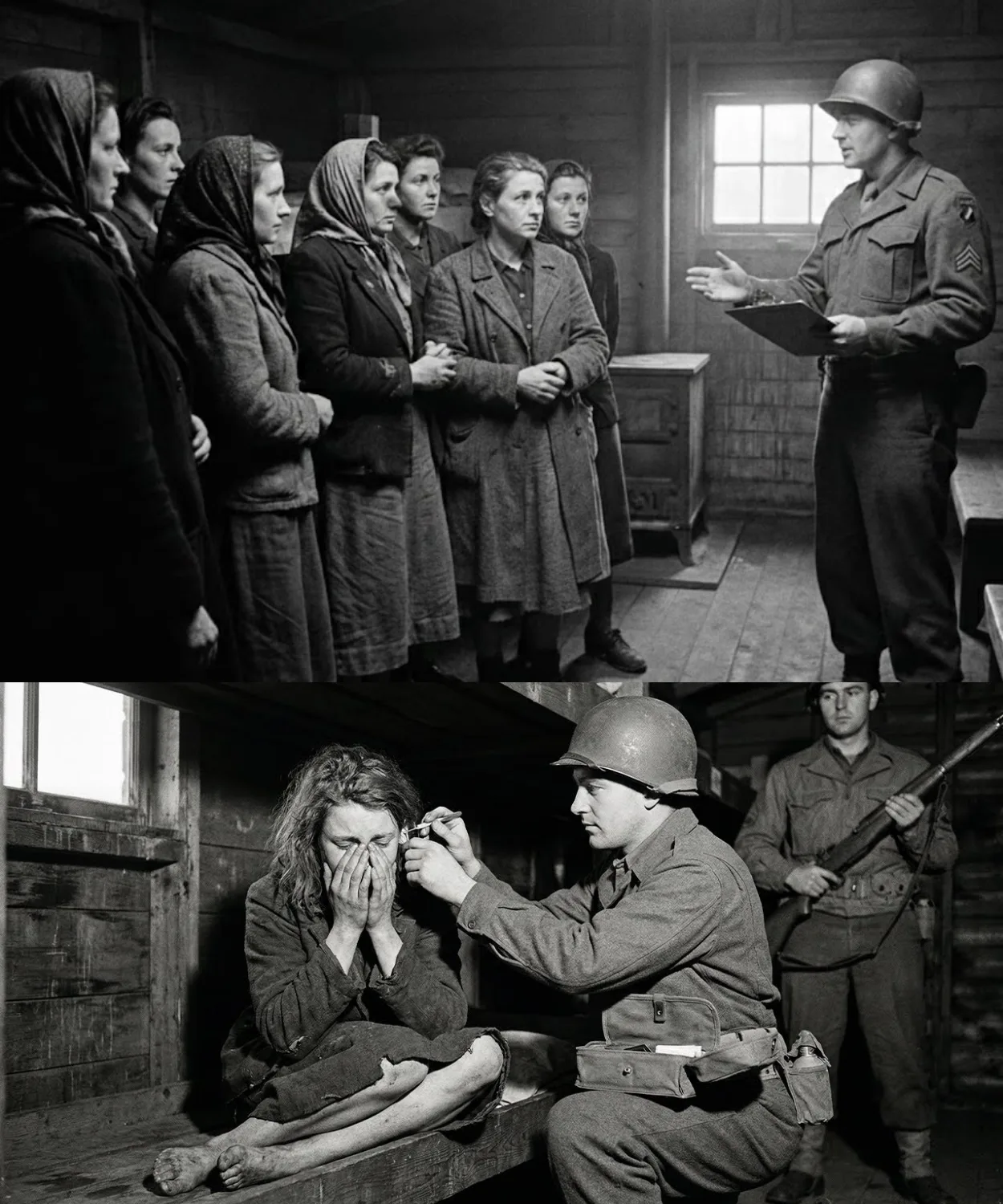

Captain Sarah Henderson of the Women’s Army Corps stood outside a processing facility watching a transport truck arrived carrying 43 German women who had been captured in the final chaotic weeks of the European War.

These were in soldiers.

They were auxiliaries, clerks, radio operators, nurses, and administrators who had been swept up in the collapse of German military command structure.

Most were between 19 and 35 years old.

All of them looked terrified.

Henderson had processed hundreds of male German PS over the past year, and she thought she knew what to expect.

soul in defiance maybe or resignation or fear of mistreatment based on Nazi propaganda about what Americans did to prisoners.

What she wasn’t prepared for was the physical condition of these women.

They weren’t just thin.

They were emaciated, holloweyed, their uniforms hanging on skeletal frames.

Their skin was shallow, their hair dull and brittle.

Several were limping.

Two had to be helped off the truck by their companions.

And the smell, even from 20 ft away, was overwhelming.

These women hadn’t bathed in weeks, possibly months.

As the women were lined up for initial processing, Henderson noticed something else.

They were watching the American guards with an expression she couldn’t quite identify.

It wasn’t fear.

Exactly.

It was more like desperate hope mixed with disbelief.

as if they couldn’t quite believe something they desperately wanted to believe.

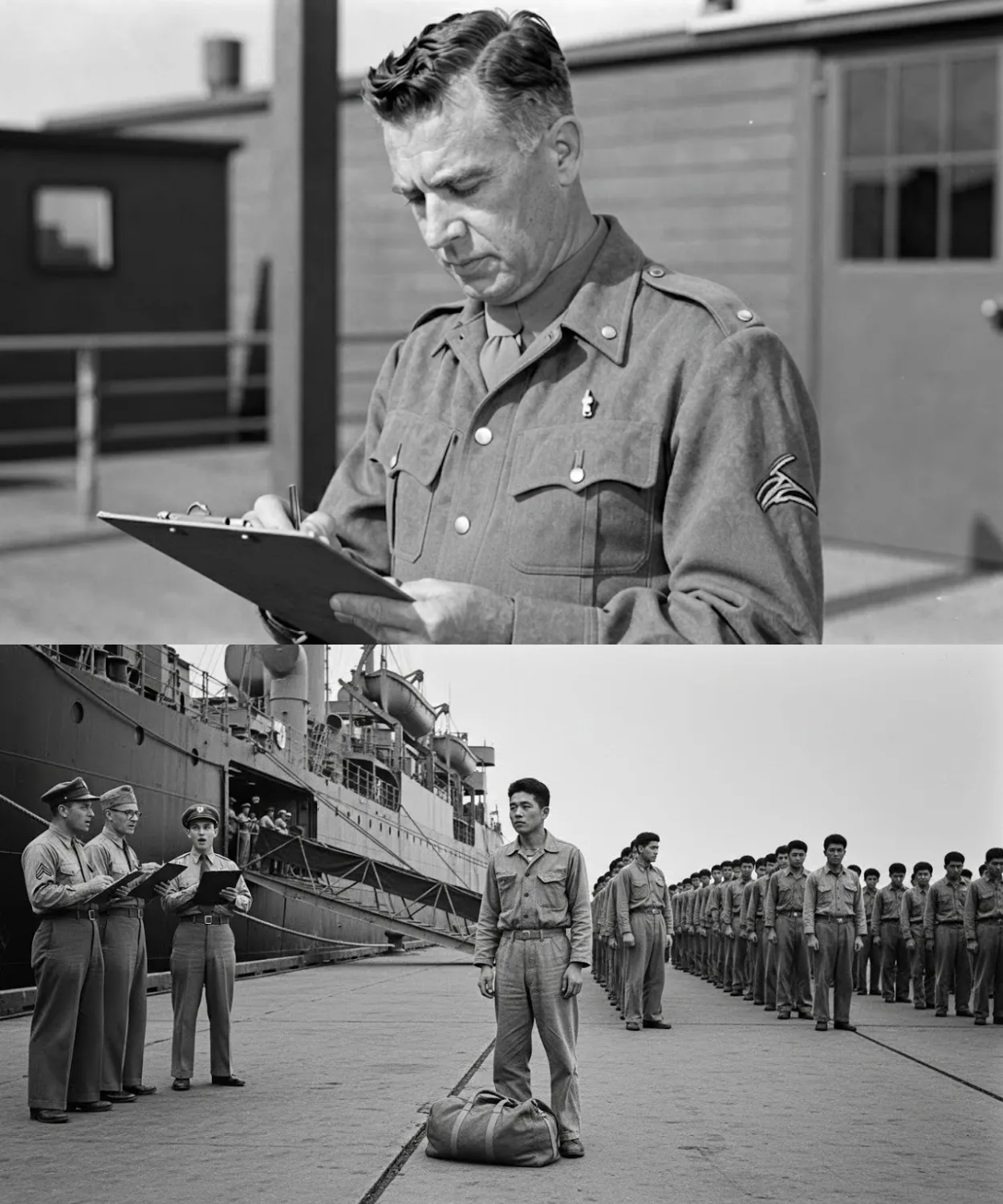

The standard processing procedure was straightforward.

Medical examination, dousing, shower, issuance of clean prison clothing, assignment to barracks.

Henderson had done this routine hundreds of times.

But as she looked at these particular prisoners, something told her this wasn’t going to be routine at all.

She called over Sergeant Mary Kowalsski, who spoke fluent German, to help with translation.

“Tell them they’ll be medically examined, then taken to shower facilities where they’ll be given soap and clean clothing,” Anderson instructed.

Kowalsski translated.

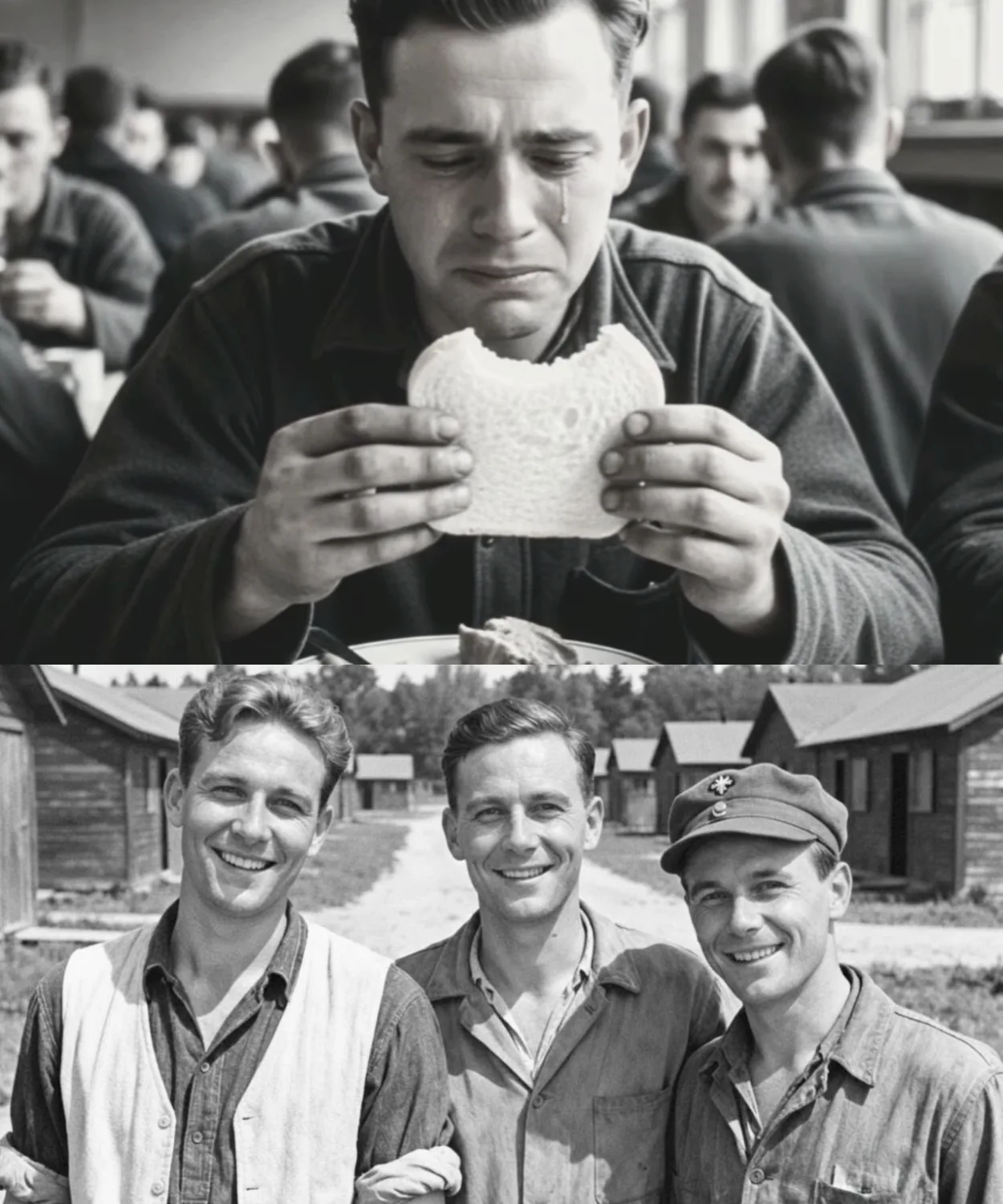

The reaction was immediate and completely unexpected.

Several of the women started crying, not quiet tears, but deep body shaking sobs.

Others simply stared at Kowalsski as if she had said something impossible.

One woman, who appeared to be in her mid20s, actually spoke up, her voice.

Soap? Real soap? You will give us soap? Kowalsski looked at Henderson, confused by the intensity of the reaction, then turned back to the woman and confirmed, “Yes, real soap for washing.

What happened next would stay with Sarah Henderson for the rest of her life.

The German woman collapsed to her knees and began crying so hard she could barely breathe.

Within seconds, more than half the group had broken down completely.

Some crying, some simply standing in shocked silence, some holding on to each other for support.

Henderson had no idea what she was witnessing.

She called for the camp doctor, Captain James Morrison.

Thinking perhaps these women were having some kind of collective mental breakdown from the stress of capture and transport.

Morrison arrived, took one look at the situation, and asked Kowalsski to find out what was happening.

Through halting translation and between Saabs, the story emerged.

These women hadn’t seen real soap in over a year.

For the past 18 months, as Germany collapsed, even basic hygiene supplies had disappeared.

What passed for soap in Germany by late 1944 was a gray brown substance made from clay, ash, and industrial chemicals that barely produced lather and often caused skin irritation.

By early 1945, even that erat soap had become unavailable.

The women described washing with cold water only, sometimes using sand to scrub dirt from their skin.

They described the humiliation of smelling their own unwashed bodies and being unable to do anything about it.

They described the shame of being unable to maintain basic cleanliness, of watching their hair become matted and their skin break out in rashes from lack of proper hygiene.

One woman, a former nurse named Greta, explained through tears, “We were told the Americans would torture us, would humiliate us, would treat us worse than animals, and you are offering us soap.

Real soap.

We have not seen such a thing in so long.

We did not believe such things still existed.” Henderson made a decision that wasn’t in any manual.

Sergeant Kowalsski, tell them the medical examination can wait an hour.

Take them to the shower facilities now.

Give them all the soap they want.

Hot water, clean towels.

Give them time to be clean again.

The shower facility at Camp Gruber was a standard military setup.

Nothing fancy.

concrete floor, multiple showerheads, institutional fixtures, but it had abundant hot water and shelves stocked with bars of standardissue military soap.

The same soap American soldiers used.

Nothing special, just basic lie soap that smelled faintly of disinfectant.

To the German women walking into that room, it might as well have been a luxury spa.

Henderson and Kowalsski had brought along female guards to supervise.

Standard procedure for security, but what they witnessed wasn’t a prison shower.

It was something closer to a religious experience.

The women approached the soap bars with reverence, picking them up carefully as if they might break.

Several held the bars to their noses and simply breathed in the smell of cleanliness.

When the water was turned on and steam began to fill the room, multiple women started crying again.

One elderly woman, probably in her 50s, stood under a shower head, letting hot water pour over her fully clothed, just feeling the sensation of warmth and cleanliness.

Eventually, she began removing her clothing, revealing a body ravaged by malnutrition and months without proper hygiene.

The transformation took nearly 2 hours.

The women washed their hair multiple times using soap with a kind of desperate thoroughess that spoke to how long they had gone without.

They scrubbed their skin until it turned pink.

They washed their clothing in the showers, ringing it out and washing it again.

Some women simply stood under the hot water, crying quietly.

Months or years of accumulated shame and deprivation washing away.

Sergeant Kowalsski, watching this unfold, turned to Henderson with tears in her own eyes.

Captain, I don’t think we understood what it was like over there at the end.

These women, they’re not enemy combatants.

They’re victims of the same regime we were fighting.

The medical examinations that followed revealed the full extent of what these women had endured.

Chronic malnutrition, vitamin deficiencies causing scurvy and other conditions, skin infections from lack of hygiene, dental problems from inadequate diet, respiratory issues from poor living conditions.

One woman had been walking on a broken foot that had never been properly set because medical care wasn’t available.

Dr.

Morrison wrote in his medical report that night, “The physical condition of these prisoners suggests prolonged severe deprivation extending well beyond what would be expected from recent combat operations.

Evidence indicates systematic breakdown of civilian infrastructure and collapse of basic public health measures.

Recommend full nutritional rehabilitation and extended medical care.” Over the following days, as the German women recovered physically and began to trust their capttors, more stories emerged.

They described the final months in Germany as a descent into medieval conditions.

Food supplies had collapsed.

Water systems failed.

Electricity was sporadic at best.

Medical supplies were non-existent.

The soap shortage was just one symptom of a total infrastructure collapse.

Many of the women had believed Nazi propaganda that the Americans would treat them brutally, that surrender meant torture and death.

The cognitive dissonance of being offered soap, hot water, clean clothing, and medical care was profound.

They had prepared themselves for the worst and instead found themselves treated better than they had been treated by their own government.

In the final year of the war, Greta, the former nurse, spoke with Kowalsski several days later after she had recovered enough to process what had happened.

“I spent the war believing we were fighting for civilization against barbarism,” she said quietly.

“And then at the end, we had no soap, no food, no medicine, nothing.

We were living worse than barbarians, and the people we were told were barbarians gave us hot water and soap and treated our injuries.

I don’t know what to believe anymore about anything I was told.

The experience at Camp Gruber was repeated at other PW facilities across the United States as more German prisoners arrived in the final months and weeks of the war.

The pattern was consistent.

prisoners arriving in shocking physical condition, breakdown of basic hygiene and medical care in Germany, and profound psychological impact when treated humanely by American captors.

The soap incident, as it became known among camp staff, revealed something that military intelligence found valuable.

The physical and psychological condition of these prisoners provided evidence of just how completely German infrastructure had collapsed.

The inability to produce or distribute something as basic as soap indicated a total breakdown that went beyond military defeat.

It suggested a civilian population that had been abandoned by its own government.

For the American personnel at Camp Gruber, the incident was transformative in a different way.

Many had entered military service filled with propaganda about German efficiency, discipline, and ruthlessness.

Seeing German women cry over soap humanized the enemy in a way that no training or briefing could have prepared them for.

Captain Henderson requested and received authorization to provide additional amenities for the female PWs beyond standard requirements.

Better food, access to reading materials, opportunities for recreation, medical care that went beyond treating immediate conditions to addressing long-term health issues caused by prolonged deprivation.

Her reasoning stated in an official memo was blunt.

These women are not criminals.

They are victims of the same regime we fought to defeat.

Treating them humanely serves our values and demonstrates the difference between democratic societies and totalitarian ones.

The memo made its way up the chain of command and eventually contributed to policy changes regarding treatment of German civilian prisoners.

The Geneva Conventions [clears throat] required humane treatment, but Henderson’s approach went beyond mere legal compliance to active rehabilitation and dignity.

In the months following the war, as the German women at Camp Gruber were eventually repatriated to occupied Germany, many maintained correspondence with the American personnel who had supervised their imprisonment.

The letters revealed a consistent theme.

The soap and shower incident had been a turning point in their understanding of the war and its meaning.

One letter from Greta to Sergeant Kowalsski, written in halting English, captured it perfectly.

You gave us soap when we expected torture.

You gave us dignity when we expected humiliation.

You showed us what humanity looks like when it is not twisted by propaganda and hate.

I will never forget standing in that shower room holding real soap and understanding for the first time that everything I had been told was a lie.

Thank you for treating us like human beings when we did not expect to be treated as such.

The incident became part of the oral history of Camp Gruber, but wasn’t widely documented in official records.

It was too small, too personal, too focused on basic human needs to fit into the grand narrative of military operations and strategic victory.

But for the people who were there, both guards and prisoners, it represented something profound about the difference between societies that maintain their humanity even toward enemies and those that abandon it, even toward their own people.

Sarah Henderson retired from the army in 1946 and worked as a social worker in Oklahoma for the next 30 years.

When asked about her most significant wartime experience, she never talked about processing thousands of prisoners or managing camp operations.

She talked about the day 43 German women cried because someone offered them soap.

“We won the war with tanks and planes and ships,” she would say.

But we won the peace by remembering that even enemies are human beings who deserve basic dignity.

Those women taught me that sometimes the most powerful weapon is simply treating people decently when they expect cruelty.

A bar of soap and some hot water did more to defeat Nazi ideology in those women’s minds than any amount of propaganda or re-education could have accomplished.

The story of the German women who cried over soap is a footnote in the vast history of World War II.

But it reveals a truth that transcends military history.

The measure of a society’s values isn’t how it treats its heroes.

It’s how it treats those who have no power and no claim to kindness.

And sometimes the most profound moments of a war aren’t the battles.

They’re the quiet instances when basic human decency breaks through years of propaganda and reminds everyone involved that underneath uniforms and ideologies, people are just people who need soap and hot water and the dignity of cleanliness.