December 2nd, 1944.

Camp McCoy, Wisconsin.

The wind hit us before the guards did.

The moment the train doors groaned open, the winter air of America crashed into us like a blade.

I had felt cold before.

Berlin nights when the power went out, those long hours hiding in basement during bomb raids.

But this was something else.

This was a cold that broke through cloth, skin, and bone.

It stole the breath from your throat before you could swallow it.

Snow whipped through the open doorway, thick and blinding, the kind of white out I had only ever seen in news reels of the Arctic.

Back home, Berlin’s winters had been gray, wet, and miserable.

But there were limits.

America, I learned in a single breath, did not believe in limits.

We were herded forward without a shove or a shout, but fear made us stumble as if we were being driven by whips.

My coat was the thin lofwafaisssue wool I had worn since 1942, patched twice, sleeves frayed.

My shoes were cracked from months of marching.

underneath nothing but a single shirt, a thin scarf, and a body that had lived too long on too little food.

The icy platform pitched beneath my feet as if God himself wanted to knock me over.

Someone behind me gasped.

My God, we’ll die out here.

I believed her.

I clutched the canvas bag that held everything I owned in the world.

a comb, a torn photograph of my brother, and an extra pair of socks with a hole in the heel, and stepped down onto American soil for the first time.

The snow swallowed my shoes up to the ankle.

The wind tore into the gap between my scarf and collar, a sharp, merciless intrusion that made my eyes water instantly.

I looked up, bracing for what we had been told to expect.

In France, in the holding camps near Sherborg, the officers had whispered about America with a kind of grim satisfaction, as if the threat of it justified every cruelty the Reich inflicted on its enemies.

They beat prisoners until their bones break.

They make women work in the snow without food.

They don’t see Germans as people, only as animals.

So when I finally saw the Americans waiting for us, my body tensed for the blow, but the blow never came.

They stood there in heavy coats and furlined gloves, breath fogging in the frigid air.

Their rifles were slung casually over their shoulders, not pointed.

No one shouted, no one pushed.

They seemed patient, almost bored.

Then came the moment that split my world in half.

A woman, an older civilian wrapped in a thick wool coat and a red knitted scarf, stepped forward.

She did not belong to the military.

No helmet, no insignia, just a sturdy Wisconsin grandmother with cheeks red from the cold and eyes sharp as needles.

She glanced at me, at my inadequate clothes, at the way I was shivering so violently my teeth knocked together, and without asking permission, she reached out and grabbed my hand.

“Come on, honey,” she said, her voice warm and startlingly gentle.

“You’ll freeze standing like that.” Honey, a stranger, an American, a woman from the land where we expected hatred and punishment, called me Honey.

Behind her, a soldier pulled open a crate and tossed thick gloves to the women nearest him.

Another handed out wool blankets, heavy and rough, but warm enough to feel like a miracle.

A third guard held out steaming cups of something that smelled like cocoa.

No shouts, no blows, no humiliation, just help.

For a heartbeat, no one moved.

We were too stunned to trust it.

Then one woman, braver than the rest of us, reached for a blanket.

The guard nodded at her, just nodded as if he were handing a coat to a neighbor, not a prisoner.

That was when my knees nearly buckled because nothing, absolutely nothing, in my understanding of this war, made room for a moment like that.

Behind us, another train whistle echoed.

In the distance, across the endless white fields, I could see smoke rising from chimneys, warmth somewhere out there in the frozen American wilderness.

I remembered something one of the guards in France had muttered before we were shipped out.

America has more PS than it knows what to do with.

They treat them well because they can afford to.

In that moment, I understood what he meant.

It was December 1944, one of the coldest winters the Great Lakes had seen in a decade.

And yet, America had the fuel, the food, and the willpower to keep not just its own soldiers alive, but hundreds of thousands of prisoners like me.

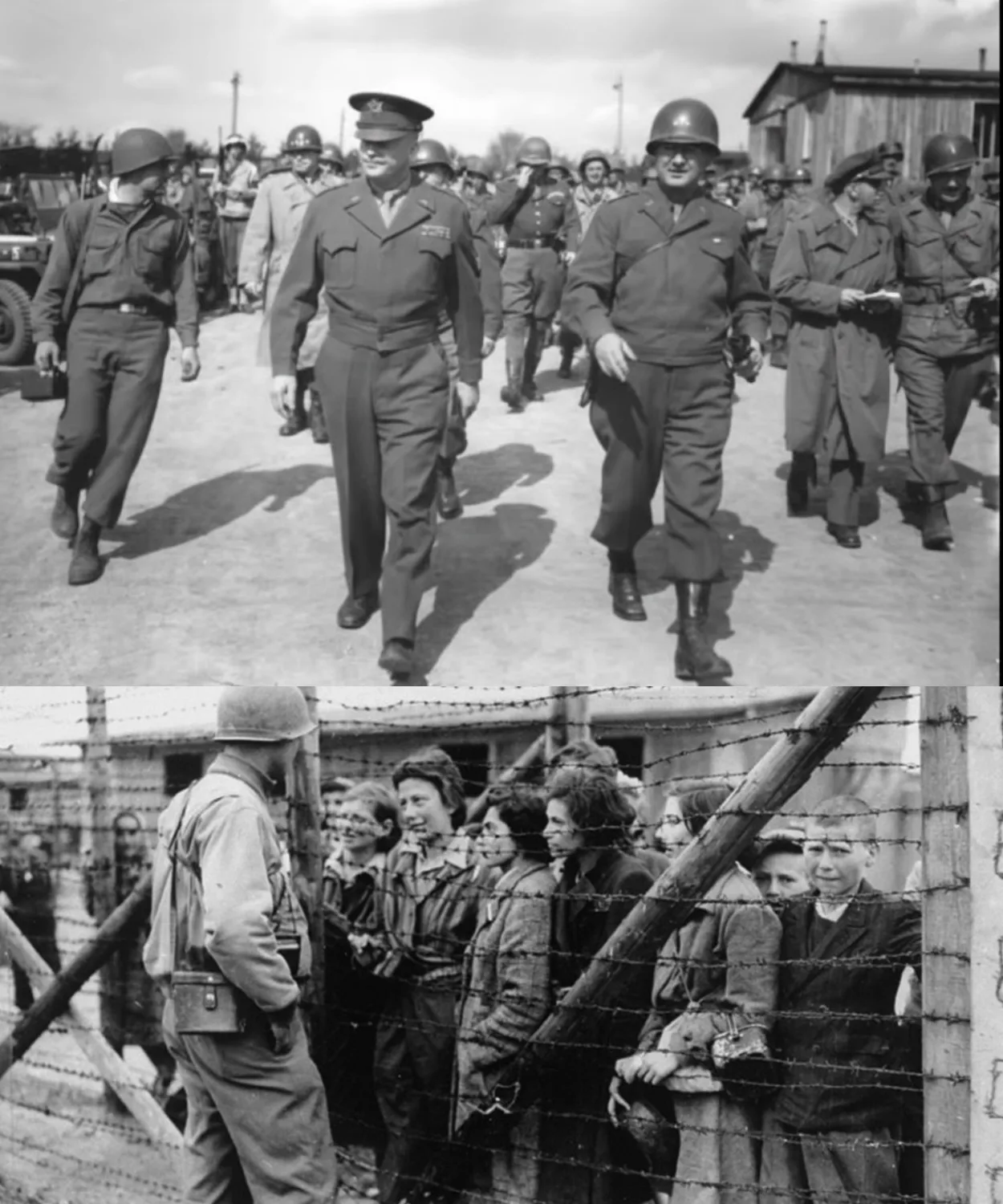

Over 370,000 Germans, Italians, and Japanese were being housed across the United States, fed and clothed while the war still raged.

Meanwhile, back home, Berlin was being pounded into dust.

People were burning furniture to stay warm.

Mothers boiled weeds for soup.

Entire neighborhoods vanished under British and American bombings.

And here I stood, a luftwafa auxiliary, an enemy being handed a blanket and a pair of gloves.

The wind howled across the platform, lifting loose snow into ghostlike shapes that danced around us.

But inside the cocoon of wool that the Americans wrapped around my shoulders, something else stirred.

Heat, yes, but also a feeling I couldn’t name.

shock, confusion, and beneath both, the faintest ember of something forbidden.

Hope.

I didn’t trust it yet.

None of us did.

But as that Wisconsin woman tugged my hand again and guided me toward a truck warmed by a coal stove, I realized the truth.

The cold might kill me, but the Americans the Americans might save me from it.

And that was the most terrifying revelation of all.

If the cold was the first shock America delivered, the second came from inside my own mind.

Because as the truck carrying us toward Camp McCoy rumbled down the snow choked road, I realized something horrifying.

Nothing the Americans had done so far matched what Germany had told us to expect, and that terrified me more than the winter ever could.

For years I had lived inside a world built from lies, comfortable lies, patriotic lies, lies repeated so often they hardened into truth.

But on that icy December day, wrapped in an American blanket and sipping cocoa, I didn’t dare admit tasted good, those lies began to unravel, and fear, real fear, took their place.

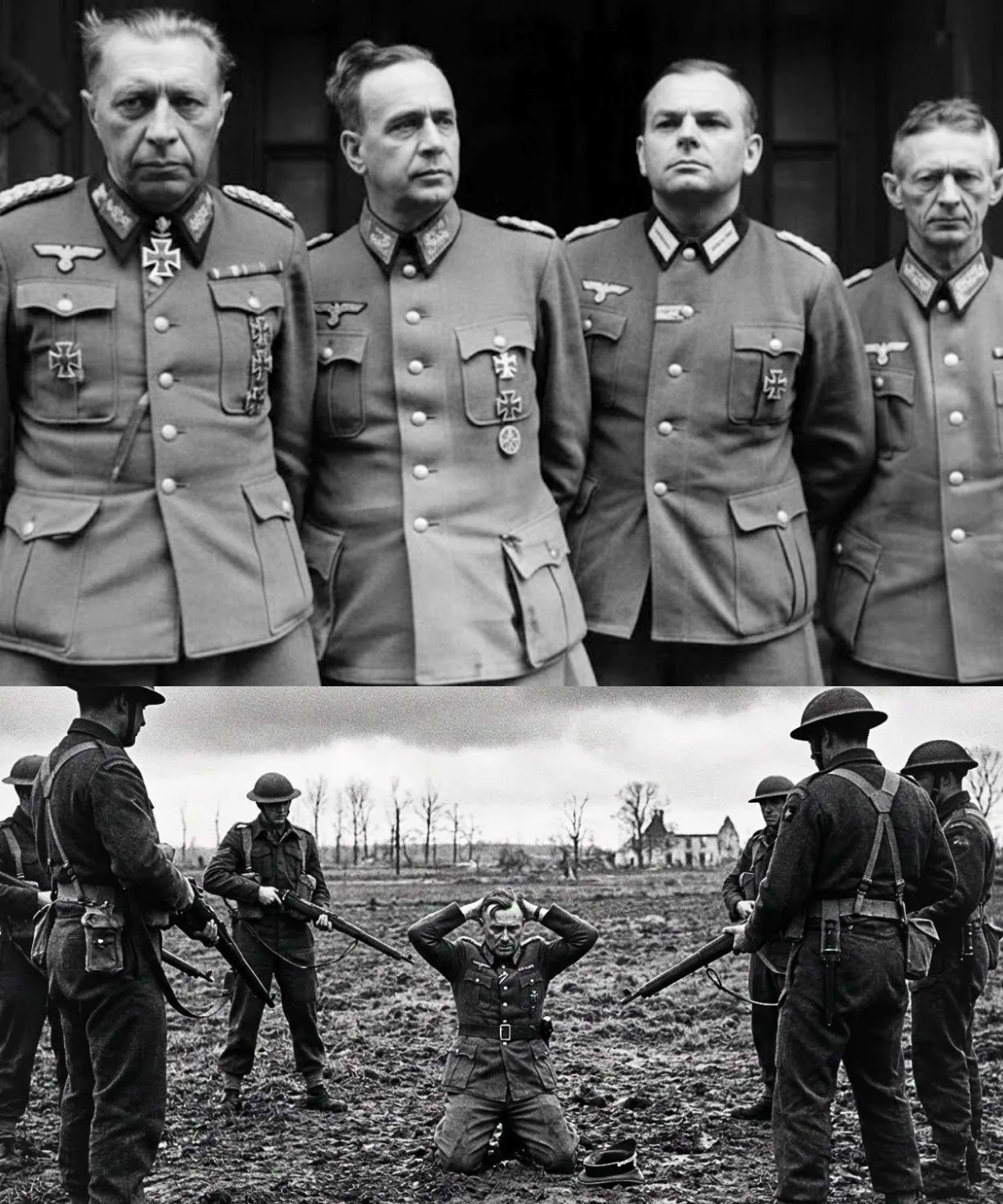

Back in Germany, fear was the air we breathed.

Every poster, every news reel, every political meeting hammered the same message into our bones.

Americans torture PS.

They use women as experiments.

They are racially weak, morally corrupt, and filled with hatred toward Germans.

Capture means shame.

Capture means you no longer deserve dignity.

Those words were not suggestions.

They were certainties repeated by officers, whispered by civilians, baked into the culture.

When they captured me near Ka, I spent the first night waiting for violence.

When they put us on a Liberty ship, I waited for hunger.

When we crossed the Atlantic, I waited for the moment they’d throw us overboard to lighten the load.

Many of the women whispered the same thoughts in the darkness of the ship’s hold.

We won’t live long enough to reach America.

We expected starvation, humiliation, punishment.

We expected to be treated the way Germany treated its own prisoners.

What none of us expected was respect, and that in a twisted way was more frightening, because if our enemy was not a monster, then what did that make the people who had taught us to hate them? After a night in the truck warmed by a coal stove, we were loaded again onto a long military train that cut north through Illinois and into Wisconsin.

It was on that train that the true scale of my fear surfaced.

I pressed my face to the window, expecting desolate wasteland.

Instead, I saw an entire world that should not have been possible during a global war.

First came the factories, vast brick giants with smoke stacks belching steam into the winter sky.

Building what? How much? For how long? Then came the trains.

mileong chains of box cars and flatbeds carrying tanks, planes, crates, fuel, an ocean of steel and movement.

Each time one thundered past, the entire carriage rattled as if acknowledging a power too large to ignore.

Then the farms, endless fields buried under snow, dotted with barns big enough to swallow the neighborhoods where I had grown up in Berlin.

Even through frostcovered glass, I saw rows of tractors, silos, and cattle that looked healthier than most Germans I knew.

I gripped the seat as the truth sank in.

If they wanted to kill us, they wouldn’t need to waste resources doing it.

A country like this could end a life without lifting a finger.

The real America was nothing like the propaganda picture we’d memorized.

Germany had told us America was chaotic, decadent, collapsing under its own weight.

But through that train window, I saw a nation bursting with motion and purpose, a place where even the land seemed to hum with energy.

For the first time, I understood how hopelessly outmatched we had been, and fear turned into something deeper, a painful, humiliating awe.

In 1944, America was not merely a country at war.

It was the Arsenal of democracy, a title I had heard whispered, but never comprehended until I saw it with my own eyes.

In that single year, the United States produced 96,000 aircraft, 8 million tons of ships, 300,000 trucks, hundreds of thousands of rifles, shells, engines, radios, uniforms, and boots.

boots thicker and warmer than anything our frontline soldiers had seen in years.

Meanwhile, Germany was crumbling.

Fuel was rationed to drops.

Civilians fought over scraps and bombed out markets.

Entire cities starved.

Rubble piled where homes once stood.

Even before I left Europe, I had seen mothers faint in ration lines.

I had seen children sift through rubble for firewood.

I’d seen my own mother shiver under blankets that did nothing to stop the bitter Berlin wind.

But I didn’t understand the contrast until I saw America’s abundance from the train.

How could Germany, a country scraping the bottom of every barrel, have believed it could defeat this? To a P, this was not just history.

It was humiliation carved into steel and smoke.

As the train pushed deeper into Wisconsin, the rhythm of the wheels brought back memories I had tried to bury.

I remembered the nights in Berlin when the sky turned orange with fire.

I remembered holding my brother’s hand as we ran through streets filled with glass.

I remembered the thud of distant bombs vibrating through the soles of my shoes.

And I remembered the day my mother died.

She had wrapped her coat around me instead of herself.

She had given me her last piece of bread.

When she finally collapsed in the kitchen, her fingers were blue.

The doctor said it was pneumonia, but everyone knew it was starvation.

I closed my eyes and let the memory wash over me.

Germany had promised us greatness, but it delivered only graves.

And now, as the train rolled past American farms, where cattle stood fatter than most German soldiers, I felt something sharp twist inside my chest.

Shame.

Not for being captured, for believing the lies that had kept me loyal to a country that could not even feed its own children.

When the train finally slowed and the guard shouted that Camp McCoy was ahead, I should have felt relief.

Instead, a new fear settled over me.

If America was this powerful, what would it do with people like me? But as the doors opened and that same Wisconsin grandmother from the platform reappeared, this time carrying wool hats in her arms, I understood something extraordinary.

Germany had taught me to fear my enemy.

America was about to teach me something else entirely.

if fear had followed me across the Atlantic.

Kindness met me the moment I stepped into Camp McCoy.

It arrived quietly, almost shyly, as if it didn’t want to startle us, but it did.

Every bit of it did.

The first morning the snow was falling in slow, heavy flakes.

We stood in formation, trembling, our breath rising like smoke.

A soldier approached carrying a bundle of wool mittens.

He walked along the line, stopping in front of each woman.

“Put these on,” he said.

He didn’t shout.

He didn’t throw them.

He simply held them out, waiting for us to take them.

When it was my turn, he paused, looking at my hands, blue at the fingertips.

He pressed the mittens into them gently.

Another guard followed with knitted hats, another with scarves, another with old but sturdy boots.

They checked sizes, swapping pairs when something didn’t fit.

A young soldier with freckles stopped in front of me.

“Your scarf’s too loose?” he said.

He reached out, tightened the knot under my chin, then tucked the ends into my coat.

“W’ll get you if you leave it like that.” I froze at the touch.

No German soldier had ever adjusted my clothing unless it was to inspect it.

He stepped back as if it were the most ordinary thing in the world.

Someone handed me a tin cup filled with cocoa.

Steam curled upward, warming my face.

I lifted it slowly.

The sweetness stunned me more than the cold ever had.

Later that afternoon, a group of local farmers arrived.

They were bundled in thick coats, scarves wrapped high around their cheeks.

One of them, a tall man with snow clinging to his boots, set down an axe.

You’ll need to know how to do this, he said.

He placed my hands on the handle, adjusted my grip, then stepped back.

Swing from the shoulders.

Let the weight fall.

I swung awkwardly, jarring my wrists.

He shook his head, took the axe, and demonstrated again.

The block split cleanly in two.

Another farmer showed us how to dry our shoes by the stove without burning them.

Lee leather cracks, he warned.

Give it slow warmth.

A nurse from town leaned over our hands and feet, explaining frostbite in careful, simple words.

warm water, not hot, no rubbing.

They taught us how to eat American food, how to build strength again without making ourselves sick.

We listened to every word, unsure why they cared so much whether strangers from across the ocean survived their winter.

A few days later, I was sent with a work crew to a nearby farm.

We shoveled snow from the barn roof until our arms shook.

When we finished, the farmer’s wife opened the door and called us inside.

“Come eat,” she said.

The kitchen smelled of roasting chicken and bread.

A wood stove glowed in the corner.

Two children peeked from behind a doorway, staring at us with wide eyes.

I sat at the table, unsure if I should.

The farmer’s wife placed a slice of apple pie in front of me.

Eat, dear.

Snow’s coming tonight.

Her voice was soft, the kind of voice my mother once used before the war hardened all of us.

I took a bite.

Cinnamon and warm apples filled my mouth.

I lowered my head so no one would notice my eyes welling.

The children crept closer.

One of them touched my sleeve.

“Are you really from Germany?” he asked.

I nodded.

Do you have snow there, too? Yes, I said, but not like this.

After supper, we sat near the stove to warm our boots.

The radio hummed in the background, Bing Crosby singing something slow and smooth.

Snow tapped gently against the windows.

The children played on the floor with wooden blocks.

The farmer leaned back in his chair, polishing his glasses.

His wife dried dishes with a cloth patterned in tiny blue flowers.

It felt like stepping into a world untouched by war, a world where people still trusted each other, a world where warmth was given freely without suspicion.

When we returned to the camp for the night, the guards checked us in with tired smiles.

One of them handed me another pair of socks.

“Wo,” he said.

“Keep them dry.

I lay on my bunk, listening to the wind scrape against the barracks walls.

My hands still smelled faintly of apple pie.

I could hear the faint echo of Bing Crosby’s voice in my mind.

For a long time, I didn’t sleep.

Kindness was not something I knew how to carry.

Cruelty, hunger, cold, that was familiar.

But this this gentleness, it unsettled me more than any threat.

I thought about the soldier tightening my scarf, the farmers teaching us to split wood, the nurse warming our hands, the children staring at me with curiosity instead of fear, the woman sliding apple pie across the table as if I were her guest.

Everything I had been taught about America was coming undone, piece by piece, replaced by something that felt impossibly simple.

We were not being punished.

We were being cared for.

And that terrified me more than anything that had come before.

The strangest thing about kindness is how sharply it cuts when you’re not ready for it.

Cruelty you can brace for.

Hunger you learn to endure.

But kindness, kindness hits you where you have no armor left.

And for me, it struck on a day when the snow was falling so hard it blurted the world into white.

We had been clearing a path between two storage sheds, shoveling until our shoulders burned.

The wind picked up all at once, slicing sideways across the yard.

I stumbled, blinded, the cold crawling under my clothes like a living thing.

When I bent to catch my breath, the world tilted.

The snow, the sky, the ground.

It all spun together, and I fell forward into a drift so deep it swallowed my arms.

I tried to push myself up, but my body refused.

My fingers were numb, my legs weak from days of eating more than I’d had in years, but still not enough for this work, this cold.

The snow pressed against my face, cold and soft, and for a moment I wondered if this was how it would end.

Quietly, without violence.

I didn’t hear the guard approach.

I only felt hands under my arms lifting me as if I weighed nothing.

“Easy,” he said.

He carried me into the nearest shed, where a cast iron stove glowed orange in the corner.

He knelt beside me, brushing snow for my coat, then pulled off his own gloves and placed them over my hands.

“You’re freezing,” he muttered.

“Sit here.” He moved a wooden crate closer to the stove and guided me onto it, positioning me so the heat reached my face.

My breath came in short, shuttering bursts as a feeling returned to my fingers.

First tingling, then burning.

I didn’t look at him until he crouched in front of me, checking my cheeks for frostbite.

His face was young, barely older than mine.

Snow clung to his eyelashes.

His uniform was dusted white.

When I finally lifted my eyes to his, the question escaped before I could swallow it.

Why would an enemy save me? He blinked, surprised by the tremor in my voice.

You’re a person, he said.

That’s reason enough.

I turned away as tears blurred my sight.

It wasn’t the cold.

It wasn’t the fall.

It was the unbearable weight of hearing humanity from a mouth I had been taught to fear.

Later that evening, back in the barracks, I lay on my bunk staring at the ceiling.

The girls around me whispered softly, their breath forming small clouds in the frigid air.

The stove in the corner sputtered, its heat barely reaching the center of the room.

I closed my eyes, but the guard’s words followed me.

You’re a person.

Germany had not said that to us in a long time.

I thought of all the lessons drilled into us, the posters, the radio speeches, the lectures about American savagery.

I thought about how I had believed every one of them.

And now each memory cracked like thin ice under the weight of everything I had seen in Wisconsin.

The next night, the storm arrived in full force.

The wind roared across the camp, ripping snow from the ground and hurling it against the barracks walls.

The windows rattled.

The lights flickered.

We huddled under our blankets, shivering.

The cold seeped through every gap, every seam.

A girl in the bunk below me cried softly, her breath shaking.

Then the door opened.

A guard stepped inside, snow swirling behind him.

His cheeks were red, his coat soaked at the shoulders.

He set down a bundle of extra blankets and began handing them out one by one.

“Double up tonight,” he said.

“It’s going to get worse.” When he reached my bunk, he hesitated, then draped a blanket gently across my shoulders.

I looked up at him, unsure whether to speak.

He leaned close enough that only I could hear him.

Our boys are freezing in Europe, too, he whispered.

No one deserves to freeze.

Then he moved on, continuing down the row.

A gust of wind shook the barracks, and I held the blanket tighter.

His words echoed through me, settling somewhere deep, somewhere raw.

No one deserves to freeze.

Outside, the storm raged.

Somewhere across the ocean, battles were unfolding in forests and fields torn apart by shellfire.

I pictured American soldiers fighting through snow, their breath turning to ice, their hands numb around their rifles.

I had heard whispers among the guards about a brutal fight in Belgium.

The name reached us like a chill.

The Ardens, the Bulge.

Thousands of American soldiers trapped in forests, buried under snow, surrounded, outnumbered, freezing.

19,000 dead in the cold.

And yet here, in a small wooden barracks in Wisconsin, their fellow countrymen were covering prisoners with extra blankets.

The storm outside beat against the walls.

I pressed my forehead to my knees and let the warmth of the wool seep into my skin.

Something inside me cracked.

Not loudly, not suddenly, just enough to let in the truth.

Everything I had believed was wrong.

Germany had told us Americans were monsters, but the only kindness I had felt in years came from their hands.

Germany had taught us that mercy was weakness.

But these men, strong enough to fight a world war, were gentle enough to worry about our cold feet.

Germany had promised us glory, but all it had given us was hunger, rubble, and graves.

I didn’t speak for a long time.

The girls around me slept fitfully.

The wind howled.

The blanket smelled faintly of soap and pine.

Somewhere in the dark, I felt a tear slip down my cheek.

Not because I was cold, not because I was afraid, but because I finally understood the most painful truth of all.

The enemy had given me back the humanity my own country had taken away.

F.

Winter had once felt like an enemy pressing at every window and door.

It slowly became something else during those weeks, an everpresent backdrop to a life that no longer felt like captivity.

It was strange to realize how easily routines formed, how quickly strangers became familiar, how warmth appeared in places I never expected.

It began in the classroom.

Every evening after roll call, a guard unlocked the small building near the messaul.

The air inside was always warmer than the barracks.

Lamps buzzed softly overhead.

A chalkboard leaned crooked against the far wall, smudged white from previous lessons.

Snowdrift, a guard said one night, writing the word in big letters.

We repeated it one by one.

Snowdrift.

Snowdrift.

When it was my turn, I said it more quietly.

Snow drift.

He nodded and wrote another.

Chimney.

I tried it slowly.

Chimney.

Later, another guard sketched a crude picture of fingers turning blue.

“Frostbite,” he said.

“Bad stuff.

” We wrote the words again and again, tapping our pencils against the tables when our hands grew cold.

The guards corrected us gently, repeating the words until they stuck.

Sometimes they added others: boots, stove, blanket, and laughed when one of us pronounced something so wrongly it became a new word altogether.

We left too.

It came easier each night.

Work on the farms continued.

The trucks carried us down snowy roads bordered by fences half buried under drifts.

At the Dawson farm, the gates were always open by the time we arrived.

Walkways first, Mr.

Dawson said.

He handed me a shovel.

The snow was deep and heavy, and my breath came in short bursts that fogged the air.

When my fingers stiffened, he tossed me a pair of gloves he’d kept in his coat pocket.

“Too cold for bare hands,” he muttered.

Inside the barn, the cows stood in patient rows.

Their breath made warm clouds in the cold air.

We filled their troughs, scraped frozen mud from the floor, and stacked hay until our arms burned.

The barn smelled of straw and warm milk.

Outside, wood waited to be split.

The axe felt heavier each day, but I learned the rhythm of it.

Lift, breathe, swing.

The satisfying crack echoed across the yard.

One afternoon, after I managed three clean splits in a row, Dawson stepped beside me and nodded once.

“Good work, kid.” The words startled me more than the cold wind blowing over the fields.

I kept splitting wood to hide the way my chest tightened.

Milking came next.

My first attempts were clumsy, the cow flicking her tail impatiently.

A farm hand guided my hands.

“Gentle,” he said.

“Like that.” I copied his movements until the milk streamed steadily into the pale.

Most days ended with boots caked in snow, hands chapped, and the strange feeling that despite everything, we had accomplished something.

The small human moments surprised me most.

One morning, as we cleared snow near a fence, a young boy approached, his cheeks pink from the cold.

He held a stick of chewing gum in his mitten hand.

“For you,” he said.

I hesitated, glancing at the guard.

He nodded.

I took it carefully and slipped it into my pocket.

The boy grinned before running back toward the farmhouse.

Another day, as we were preparing to leave a different farm, an older woman approached with a basket.

Her coat was buttoned crookedly, her hair tucked into a knitted hat.

“Come here,” she said, motioning me closer.

I stepped forward.

She pulled out a new wool cap, soft and thick, and settled it firmly onto my head.

“There,” she said.

“Now you look ready for winter.” Her hands lingered on the sides of the hat, adjusting it gently.

Near Christmas, the Dawson invited us inside again.

Snowflakes drifted across the windows like feathers.

Inside, the air smelled of pine and cinnamon.

A small tree stood in the corner decorated with paper chains and glass bobbles.

Mrs.

Dawson handed me a small envelope ere.

Inside was a photograph of their family standing in the yard bundled in coats.

The father had his arm around his youngest daughter.

The oldest son held the dog by the collar.

They all squinted in the winter sun.

I ran my thumb over the edges of the picture.

No one said anything.

They didn’t need to.

We helped bring firewood inside, stacking it near the stove.

When we finished, Mrs.

Dawson handed out mugs of warm milk with cinnamon sprinkled on top.

Stay by the fire, she told us.

It’s colder tonight.

Bing Crosby’s voice drifted from the radio, soft and steady.

The crackle of the stove filled the quiet spaces between songs.

The children played on the floor, giggling at a wooden puzzle.

The father polished his glasses.

The mother folded blankets by the window.

For a moment, I forgot everything outside that warm room.

When we finally left, the snow had thickened.

The walk back to the truck was silent, except for the crunch under our boots.

I held the photograph inside my coat to protect it from the wind.

In the barracks later that night, I slid it under my pillow.

The bunk felt less empty with it there.

Days passed like this.

Work, English lessons, small kindnesses that arrived unannounced.

Some mornings the guards offered us coffee so strong it made our eyes water.

Other days, children left small gifts on fence posts, candy canes, knitted mittens, a paper star folded carefully and tied with string.

One evening, as we returned from the farm, a neighbor waved from her porch.

Curtains glowed behind her, soft yellow light spilling into the snow.

“Be safe now,” she called.

“Storm coming!” It felt strange each time.

this concern, this warmth, this life woven loosely around ours as if we belonged inside it.

The war still loomed beyond the horizon.

But here, in the quiet, snow-covered fields of Wisconsin, we fed animals, learned words, shared warmth, and gathered moments that felt borrowed from another world.

And every night before I closed my eyes, I reached under my pillow to touch the corners of the Dawson family photograph, as if grounding myself in something fragile and new that I didn’t yet know how to name.

War had taught me many things, but not this.

It had taught me how to hide in basement while the ceilings shook.

It had taught me how to ignore the sound of other people crying.

It had taught me how to follow orders, how to obey, how to swallow questions, but it had not taught me what I learned one pale afternoon standing in the snow beside an old American farmer who smelled of hay and pipe smoke.

It was late January when he said the words that split my life into a before and an after.

in America,” he told me, leaning on his shovel.

Dignity isn’t earned, it’s given.

The sky was the color of tin that day, low and heavy.

We had been clearing snow from around the barn, our breath hanging in the air like ghosts.

I’d grown used to the work, the weight of the shovel, the ache in my arms, the feeling of my feet thawing slowly when we stepped inside for a break.

The farmer’s name was Walter.

His hair was more white than gray, thick beneath his cap.

His hands were cracked, the lines darkened by years of dirt.

When he stood still, he leaned slightly to one side, as if a lifetime of hard labor had pulled him gently out of alignment.

He watched me work in, silence, for a long time.

His eyes narrowed against the cold.

I kept my focus on the shovel, on the rhythm of scooping and tossing, not daring to look at him for too long.

Old men in Germany had watched like that, too, but their stairs had carried suspicion, not curiosity.

When I paused to catch my breath, he stepped closer.

“They worked you hard over there?” he asked.

I was still getting used to English, but I understood enough.

I nodded.

He studied me for a moment, then set his shovel aside.

In America, he said, dignity isn’t earned, it’s given.

The words didn’t make sense at first.

Dignity in my world had been a reward, something granted to the loyal, the obedient, the victorious.

It was something that could be taken away with a demotion, a punishment, an accusation shouted in a crowded room.

given,” I repeated.

He nodded.

“You’re a person.

That’s enough.” He said it simply, as if it were obvious, as if it had always been true.

I stared at him, the wind tugging at my scarf, the cold slowly seeping into my bones.

A dog barked in the distance.

Somewhere in the house, a door slammed.

A thin trail of smoke rose from the chimney, curling into the gray sky.

In my mind, images flickered like film strips.

My mother being told to move to the back of a line because her ration card had a mark on it.

A neighbor disappearing one night after making a joke about the party.

A boy in my class beaten by a teacher for asking why our soldiers were fighting so far from home.

No one had called those people dignified.

They had been called troublemakers, weaklings, cowards.

Here, an old farmer stood in the snow and told me my existence alone was enough to deserve dignity.

I wanted to ask him how that could be true.

Instead, I picked up my shovel and kept working, his words echoing in every scoop of snow.

Back in the camp that evening, the barracks was dim, lit by a few bare bulbs.

The stove rattled softly, dry heat rising from its belly.

I sat on my bunk with the Dawson family photograph in my hands, tracing the silhouettes of their faces with my eyes.

Dignity isn’t earned, it’s given.

The more I repeated it, the more it gnawed at the foundations of everything I had believed.

I thought of the first time I’d put on my Luftwafa uniform in Berlin.

I’d stood in front of a cracked mirror, smoothing the fabric with shaking hands, telling myself I finally mattered, that the symbol on my sleeve made me someone, that loyalty would keep me safe.

Yet the first person to treat me as if I mattered without asking for anything in return had been a foreign grandmother handing me a blanket in Wisconsin.

The first person to worry whether my ears were cold had been an American woman knitting hats for prisoners.

The first person to adjust my scarf so the wind wouldn’t cut my throat had been a young guard whose name I never asked.

The first person to say the word dignity as if it belonged to everyone had been an old farmer leaning on a shovel.

I realized I had spent years giving my faith to a system that valued uniforms more than people.

America in that winter seemed to do the opposite.

Days passed.

The routines continued.

In the morning, smoke rose from chimneys in thin gray ribbons against the white sky.

Snow lay thick across the fields, untouched except for the paths we carved with our boots and shovels.

Barns glowed with a faint warmth, their doors swinging open to reveal cows shifting lazily, their breath forming soft clouds.

Inside the farmhouses, wood stoves ticked inside, pots simmerred, radios hummed.

One Sunday, the Dawson family invited us to stay for their noon meal.

We stood awkwardly near the door at first, unsure where to go, what to do.

Mr.

Dawson motioned us to the table.

“Sit,” he said.

“You worked, you eat.

” We took our places, heads lowered.

The table was covered with a plain white cloth.

Bowls of potatoes, carrots, and meat sat steaming in the center.

Fresh bread waited on a wooden board, butter softening in a dish beside it.

Before anyone lifted a spoon, Mr.

Dawson bowed his head.

His wife and children did the same.

Lord, he said, thank you for this food, for this home, for these hands that help.

There was a brief silence.

Amen.

They murmured together.

I kept my eyes open, watching their faces.

There was nothing performative in their expressions, just weariness, gratitude, and something else I couldn’t yet name.

They gave thanks for the same things we had once been told to take by force.

Later, as I washed dishes with Mrs.

Dawson, she handed me a towel and nodded toward the window.

A storm coming tonight, she said.

January’s not done with us yet.

Outside, the sky had darkened.

The fields stretched white and endless, the fences half buried under snow drifts.

The barn stood solid against the wind, its roof lined with icicles.

The farmhouse windows glowed like beacons.

“Hard winter,” I said.

She smiled faintly.

“We’ve seen harder.” Her words carried no pride, only quiet resilience.

She handed me a plate to dry.

That night, back at camp, the wind clawed at the barracks.

The walls creaked.

Snow hissed against the glass like sand.

The guard on duty opened the door briefly to check on us.

His cheeks were red, his eyebrows crusted with ice.

“You all right in here?” he called out.

We nodded.

He closed the door quickly, sealing the warmth back inside.

I lay awake for a long time, listening to the storm.

My mind wandered through faces and places.

Berlin streets filled with rubble, crowded ration lines, officers shouting orders from podiums.

Then it drifted back to the warm barns, the steady hands of farmers, the quiet prayers before meals in Wisconsin.

The contrast was so sharp it felt like stepping between worlds.

One had told me my worth depended on my usefulness.

The other insisted I had worth simply by existing.

One had measured loyalty in how much I was willing to ignore.

The other measured character in how much I was willing to see.

I thought of Walter’s words again.

Dignity isn’t earned.

It’s given.

If that was true, then everything I had believed about strength and weakness, about victory and defeat, needed to be rearranged.

The strongest people I had known before the war were the ones who shouted the loudest, who demanded obedience, who punished anyone who hesitated.

The strongest people I knew now were the ones who shared blankets, taught us to split wood, and worried about whether our fingers were warm enough to hold a shovel.

When the storm finally passed, the world outside emerged hushed and pale.

The snow lay smooth and deep, erasing footprints and wagon tracks.

The sky turned a soft blue, almost delicate in its brightness.

We were sent out again, shovels in hand.

The barns needed clearing.

Paths needed carving a new.

As I worked, I glanced back at the farmhouse.

Through the window, I saw the Dawson family gathered at the table.

Their heads were bent again, hands folded.

Their lips moved in unison.

Snow clung to the window panes like lace.

They were praying.

They prayed before every meal, for weathered hands and simple food, for safety and warmth, for sons away at war.

I had never heard them ask for victory, only for strength, for protection, for the grace to endure.

In Berlin, prayers like that had grown quiet, replaced by slogans and salutes.

In Wisconsin, they were spoken aloud, as natural as breathing.

As I watched them, a thought rose unbidden in my mind.

If this is the enemy, then we did not know what kind of world we were fighting.

I didn’t say it.

I barely let myself think it, but it lingered like the faint smell of wood smoke on my clothes long after I left the barn.

That evening, as the sun sank in a wash of pale gold, I walked back to the camp with the others.

The sky darkened to violet, then black.

Stars pricricked through the cold air, distant and unblinking.

I looked up, my breath forming a cloud that drifted away slowly.

Somewhere under that same sky, men in uniforms that matched mine were still firing guns, still shouting orders, still clinging to the belief that fear and force could shape the world into something they could control.

Somewhere else, American boys were freezing in forests I had never seen, their names being whispered in farmhouses like the one behind me.

And here I was, a German prisoner walking through American snow, carrying a photograph of an American family under my coat, learning that my worth did not depend on what flag flew over my head.

In that moment, beneath that vast winter sky, I understood that the war might end with papers and signatures, with speeches and treaties.

But for me, its true ending had begun the day an old farmer in Wisconsin leaned on his shovel, looked me in the eye, and told me that in his country, dignity was not a prize.

It was a gift.

I left America on a gray morning in the spring of 1946.

The snow had finally melted, leaving behind soft earth and the smell of wet pine.

We boarded the trucks quietly, each of us carrying the small bundle the camp allowed, no more than what we had arrived with, except for the things we had been given.

In my bag were a pair of wool gloves mended twice by Mrs.

Dawson, a photograph of their family, edges worn from my thumb brushing it every night, and memories of a winter that had not taken my life, but had given it back to me.

When the truck pulled away from Camp McCoy, I turned once to look at the place that had changed everything.

Its wooden towers, its snowwashed fields, the faint column of smoke rising from a farmhouse chimney.

I didn’t cry.

I only held the gloves tighter.

The journey back to Germany was long.

The ship smelled of salt and iron.

The water stretched endlessly in every direction.

At night, lying in the narrow bunk, I ran my fingers over the photograph and felt the rough fibers of the wool gloves.

I kept them under my pillow the way I had in the barracks.

Germany appeared on the horizon like a bruise, dark, swollen with ruins.

The train ride inland passed shattered towns where empty windows stared back like broken eyes.

Streets that had once been loud with markets and trams were silent.

People moved like shadows, thin and hollow.

When I stepped onto German soil again, the wind carried no scent of wood smoke or bread, only dust.

My childhood street was unrecognizable.

Walls collapsed inward.

Door frames leaned.

The apartment where my mother had once hummed while hanging laundry was gone entirely, replaced by a pile of stone and memory.

For months I felt suspended between two lives, the one I had lost in Berlin and the one I had borrowed in Wisconsin.

In the evenings, when the cold crept through the cracks of the temporary shelter, I wore the wool gloves to sleep.

They were the only warmth I trusted.

Years passed.

Germany rebuilt itself, slowly at first, then with surprising speed.

New buildings rose from the rubble.

Markets reopened, schools returned.

But inside me, that winter in America stayed untouched like a photograph preserved behind glass.

When I finally wrote my account of the war, I ended it with the only words that felt true.

America did not just save my life.

America saved the part of me that was still human.

I didn’t know when I wrote those lines how far they would travel, how many hands would hold that book, how many families would recognize pieces of their own stories in mine.

Long after I grew old, letters began arriving from places I had never seen.

Nebraska, Ohio, Texas, Oregon.

Some were from the children of American guards, others from the grandchildren of farmers who had worked the land during the war.

But the most unexpected letters came from Germany, from the descendants of PWs who had lived in camps across America.

They wrote about their fathers, grandfathers, uncles, men who had returned home with stories of kindness instead of cruelty.

men who had hidden small treasures in their pockets, shirts, photographs, coins stamped United States, and sometimes wool gloves like mine.

One woman wrote, “My grandfather always said America fed him when his own homeland could not.” Another wrote, “We grew up hearing that an American farmer treated him like a son.” And a young man wrote, “Because of what America did for him, he taught us never to hate.” Some of them made pilgrimages to the old camp grounds.

Camp McCoy, Camp Swift, Camp Hearn.

They walked through empty fields, tracing the ghosts of the barracks with their hands.

They visited the small town museums, touched rusted tools and faded photographs, and left flowers at memorial stones.

A few even found the families who had helped their relatives.

They knocked on farmhouse doors and met elderly men and women who had once handed mittens and warm bread to strangers in wartime.

Some cried, some hugged, some simply sat together at old kitchen tables, drinking coffee while snow fell softly outside.

As for me, I returned only once.

It was decades later.

The barracks were gone, replaced by trimmed grass and new roads, but the fields were the same.

The smell of pine was the same.

The winter wind, even softened by age, carried the same edge.

I stood near where the classroom had been and watched snow drift over the ground.

I closed my eyes and heard voices from long ago, guards calling roll, farmers greeting us at dawn, children giggling as they offered me gum.

When I opened my eyes, I felt the old ache in my chest, that mixture of longing and gratitude that never faded.

Before leaving, I slipped the Dawson family photograph into the crook of a fence post protected inside a plastic sleeve.

The children now groan, the parents gone, but their kindness alive in a stranger’s memory.

As I walked back toward the road, the wind brushed against my face.

I pulled the wool gloves from my pocket and put them on.

They still fit.

I knew I would never see this place again.

But I also knew it had never really left me.

On the flight home, I looked down at the country spread out below.

fields, rivers, small towns, cities glowing like constellations, and felt a single thought rise, quiet and sure.

If a nation could show mercy in the darkest war in history, then a nation could find that mercy again, and somewhere in living rooms across America.

I hope those words reach the people who need to hear them most.

People who wonder what became of the country their parents and grandparents knew.

People who ache for a time when kindness felt simple.

When neighbors trusted one another.

When dignity was something offered freely.

I hope they look at their own reflections in the dark of the screen and ask the question that still echoes in my heart.

Are we still that America?