The smell of fresh bread reached them before the camp did.

The trucks had been climbing for nearly an hour, winding through the forested mountains of South Central Pennsylvania on roads that grew narrower with each passing mile.

The prisoners, 47 men packed into canvas covered army transports, had grown accustomed to the smell of diesel and sweat, and the particular mustiness of military canvas.

They had expected nothing else.

But now, as the trucks rounded a final curve and began their descent into a valley nestled among the ridges of the Appalachian Mountains, something changed.

The air itself was different.

Cool, clean, scented with pine and hemlock, and impossibly the warm, yeasty fragrance of baking bread.

It was September 1944.

The prisoners were German soldiers, Vermached infantrymen, most of them captured during the Allied push through France in the weeks following D-Day.

They had been processed through camps in England, shipped across the Atlantic, and transported by train to Pennsylvania before being loaded onto trucks for this final journey into the mountains.

They expected a prison.

They expected barbed wire and guard towers and the cold efficiency of military captivity.

They expected what prisoners had always expected, deprivation, discipline, the grinding routine of confinement.

They did not expect what they found instead.

Camp Pine Grove Furnace sat in a shallow valley surrounded by the ancient hardwood forests of Misho State Forest.

The first thing the prisoners noticed as the trucks rumbled to a stop and the canvas flaps were thrown open was the architecture.

Not the stark wooden barracks of a hastily constructed military facility, but something else entirely.

Stone buildings with steep roofs and wide porches, wooden structures that looked like they belonged in a resort catalog rather than a prisoner of war compound.

and that they would soon learn was exactly what they had once been.

Before the war, this valley had been home to the Pine Grove Furnace Hotel, a mountain retreat where wealthy families from Philadelphia and Baltimore had escaped the summer heat.

The hotel had featured comfortable rooms, scenic hiking trails, a lake for swimming and fishing, and cuisine that attracted guests from across the eastern seabboard.

Now it held German prisoners of war, but remarkably much of its character remained.

The stone buildings still stood, converted to administrative offices and housing.

The wooden structures still dotted the valley, repurposed as barracks, but retaining the generous proportions of vacation accommodations.

The lake still reflected the forested ridges.

The trail still wound through the surrounding wilderness, and the kitchen, it seemed, still knew how to bake bread.

Hinrich Vber was among the first to climb down from the trucks that September afternoon.

He was 24 years old, a former factory worker from Dooldorf, who had been conscripted into the Vermacht in 1942 and sent to fight in France in the summer of 1944.

His unit had been shattered in the hedge country of Normandy and he had surrendered to American forces near St.

Low in late July.

One of thousands of Germans captured during the breakout that followed Operation Cobra.

He had been a prisoner for 6 weeks now.

He had learned to expect nothing and want less.

The camps in England had been adequate.

Food was scarce but sufficient.

Treatment was correct if impersonal.

The future was uncertain, but survival seemed possible.

But this place, this valley, with its stone buildings and forested ridges, and the impossible smell of fresh bread, this was something he could not have imagined in his most optimistic dreams.

A guard directed the prisoners toward a large wooden building that served as the camp’s messaul.

They shuffled forward in the disciplined column that had become second nature, eyes scanning their surroundings with the weariness of men who had learned that good things rarely came without cost.

The messaul doors opened.

The smell of bread intensified, joined now by other aromomas, roasting meat, fresh coffee, something sweet baking in the ovens.

Weber stopped in the doorway, unable to move.

The tables were set with metal trays as expected.

But the food on those trays was not what any prisoner had experienced in years.

Bread, white bread, soft and fresh, not the dark sawdust laden stuff that had become standard in Germany since 1942.

Meat thick slices of roast beef, pink at the center, glistening with juice.

Potatoes mashed with what appeared to be real butter.

Green beans cooked with bacon and coffee.

the dark, rich aroma of real coffee, not the Zot’s grain substitute that had replaced it throughout the Reich.

Vber stood frozen in the doorway as other prisoners pushed past him, equally stunned, moving toward the food with the uncertain gate of men who suspected a trick.

A guard noticed his hesitation.

“Go on,” the American said, not unkindly.

“Eat.

There’s plenty more where that came from.” “Plenty more.” The words made no sense.

Weber had not heard them in years, not since before the war, not since the rationing had begun, not since every mouthful had become a calculation of survival.

He walked to a table and sat down.

He picked up a slice of white bread and held it for a moment, feeling its softness, its warmth.

He raised it to his face and inhaled, and then, without warning, he began to cry.

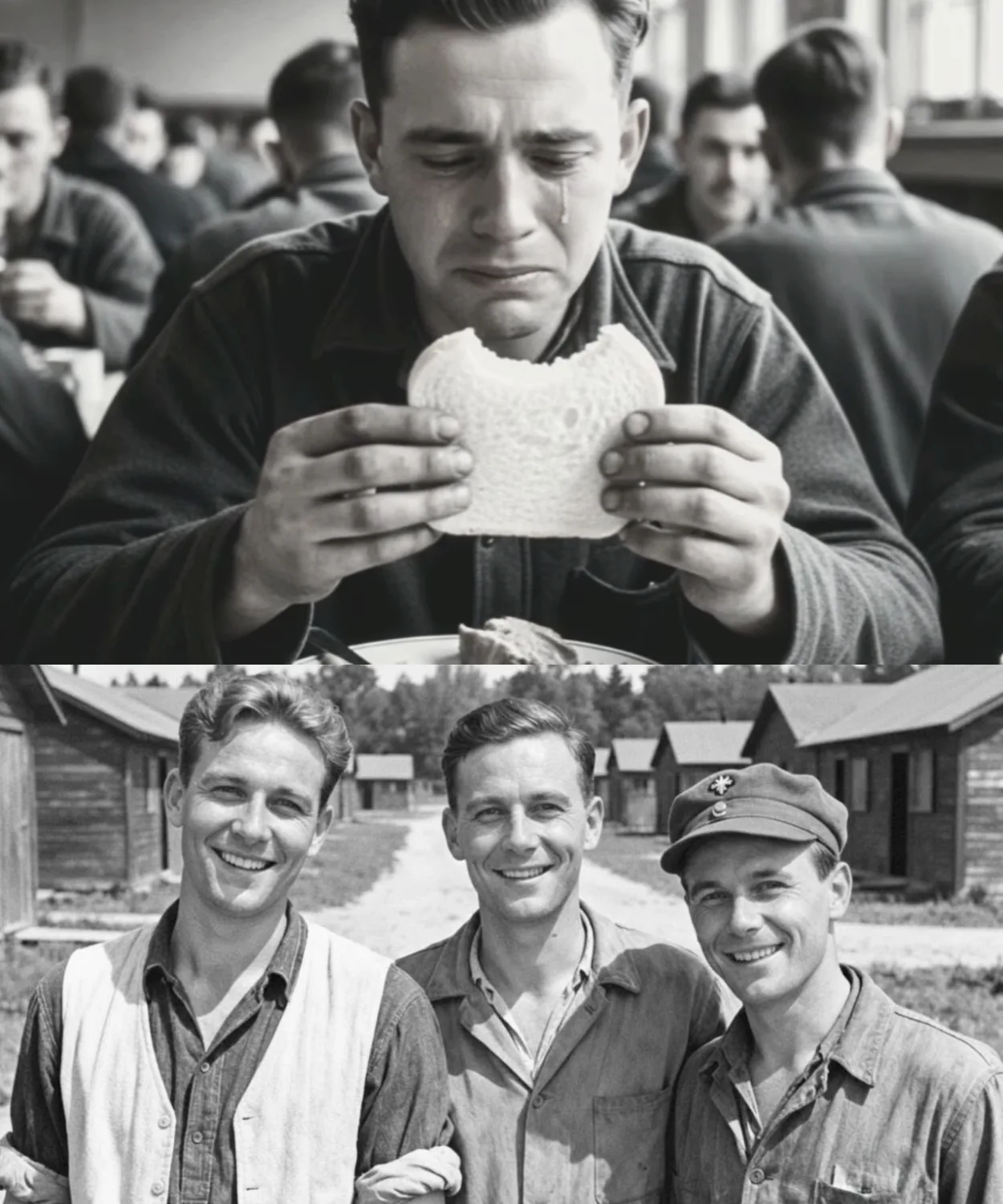

A photograph exists in the archives of the Cumberland County Historical Society.

It shows a group of German prisoners seated at long tables in what appears to be a dining hall.

The men wear simple workclo, their hair recently cut, their faces clean shaved.

On the tables before them are plates of food, meat, bread, vegetables in quantities that seem almost theatrical.

The photograph is labeled German PS Furnace 1944.

The faces of the prisoners are difficult to read.

Some appear to be eating with focused determination.

Others seem almost dazed, as if unable to process what is happening.

One man in the corner of the photograph is not eating.

He is simply holding a piece of bread, staring at it as if it might disappear.

The photographer captured something that statistics cannot convey.

The shock of abundance after years of scarcity.

The emotional weight of a simple meal.

The way food can carry meaning far beyond mere nutrition.

The prisoners had expected captivity.

They had found something that to men who had survived the deprivations of wartime Germany felt almost like paradise.

The word spread quickly through the German P network.

Letters home filtered through military sensors described conditions that families in Germany found difficult to believe.

Letters between camps shared among prisoners who had been transferred or who communicated through official channels carried the same message.

Pine Grove Furnace was different.

The food was abundant unlimited, some said, though the official policy simply followed Geneva Convention requirements that prisoners receive rations equivalent to those of the detaining powers garrison troops.

The setting was beautiful forested mountains, a clear lake, hiking trails that prisoners were occasionally permitted to use under supervision.

The treatment was humane guards were professional.

Violence was rare.

The atmosphere was more that of a work camp than a punishment facility.

Some prisoners used a word that given the circumstances should have been absurd.

But they used it nonetheless in letters and conversations and memories that would persist for decades after the war.

They called it heaven.

Not because captivity was pleasant.

It was still captivity.

still separation from family and homeland, still the fundamental loss of freedom that defines prisoner status.

But because compared to what they had left behind in Germany, the rationing, the bombing, the constant fear and deprivation, this mountain valley in Pennsylvania offered something they had almost forgotten was possible.

Enough.

Enough food, enough safety, enough of the basic dignities that war had stripped away.

For men who had learned to survive on less, enough felt like paradise.

To understand what the prisoners found at Pinerove Furnace, one must first understand what they had left behind.

By 1944, Germany was starving.

The Reich that had promised prosperity and expansion was now struggling to feed its own population.

Allied bombing had disrupted transportation networks, destroyed food processing facilities, and made agricultural production increasingly difficult.

The eastern territories that had once provided grain and meat were falling to Soviet advances.

The yubot campaign that had tried to starve Britain into submission had failed, and now Germany itself faced the consequences of total war.

Rationing had been in effect since 1939, but by 1944, the allocations had shrunk to levels that barely sustained life.

Meat was a rare luxury, available only a few times per month, and then in quantities measured in ounces rather than portions.

White bread had disappeared entirely, replaced by dark loaves, stretched with sawdust, potato flour, and whatever fillers could be found.

Coffee was a memory replaced by roasted grain substitutes that bore no resemblance to the real thing.

The soldiers at the front received priority allocations, but even their rations had declined as the war turned against Germany.

By the time Hinrich Vber and his fellow prisoners surrendered in France, they had been subsisting on reduced combat rations for weeks, hard bread, tinned meat when available, water when they could find it, and then they arrived at Pinerove Furnace.

The camp had been established in 1943 as part of the massive expansion of the American P system.

The old Piner Grove Furnace Hotel, which had closed during the depression and never reopened, provided an ideal foundation for a prisoner facility.

The existing buildings could be adapted for military use.

The remote location deep in the mountains of Adams County, far from major population centers, offered natural security.

The surrounding Misho State Forest provided ample opportunities for the lumber and forestry work that would occupy the prisoners.

The War Department formally designated the site as a branch camp under the administration of the larger facility at Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania.

The first prisoners arrived in late 1943 and by 1944 the camp held several hundred men, primarily German soldiers captured in the North African and Italian campaigns, supplemented later by prisoners from the fighting in France.

The physical layout preserved much of the resort’s original character.

The main stone building, once the hotel center, became the camp headquarters.

Wooden cottages that had housed vacationing families now served as prisoner barracks more spacious and comfortable than the standardized structures at most P camps.

The dining hall, formerly the hotel restaurant, continued to serve meals, though now to prisoners rather than paying guests.

Even the lake remained a peaceful body of water that reflected the forested ridges and reminded the prisoners of mountain landscapes in their own homeland.

The Geneva Convention of 1929 governed the treatment of prisoners of war, including provisions for food and shelter.

Article 11 specified that prisoners were entitled to rations equivalent in quantity and quality to that of troops at base camps.

The United States, as a signatory to the convention, was legally obligated to feed its prisoners the same food that American soldiers received.

In practice, this meant that German PS in American camps often ate better than they had in their own army, and far better than the civilian population they had left behind in Germany.

A typical daily ration at Pine Grove Furnace included breakfast, oatmeal or eggs, toast with butter, jam, coffee with sugar and cream, lunch, soup, sandwiches with meat or cheese, fruit, milk or coffee, dinner, roast meat, beef, pork or chicken, potatoes, vegetables, bread, dessert.

The quantities were generous.

Seconds were often available.

Waste unthinkable in Germany was common enough that prisoners sometimes saved scraps not from hunger, but from an inability to believe the abundance would continue.

A report from the Prost Marshall General’s Office in 1944 noted that newly arrived prisoners frequently require time to adjust to American ration levels and observed that some prisoners initially refused to eat, convinced the food was somehow poisoned or drugged, unable to accept that such abundance was simply normal.

At Pinerrove Furnace, the combination of adequate housing, scenic surroundings, and plentiful food created conditions that prisoners found almost impossible to reconcile with their expectations of captivity.

The daily routine at the camp balanced work with recreation in ways that surprised the prisoners.

Wake call came at .

Breakfast was served at .

By , work details assembled for transportation to job sites throughout the surrounding forest and region.

The primary labor was forestry work, cutting timber, clearing brush, maintaining fire brakes in Micho State Forest.

The work was physically demanding but not punitive.

Prisoners used professional equipment, cross-cut saws, axes, logging tools, and were trained in techniques by American civilian foresters who supervised the operations.

Some prisoners were assigned to agricultural work on farms throughout Adams and Cumberland counties, helping with harvests that local farmers could not manage with their young men away at war.

Others worked at a local apple processing facility, sorting and packing the fruit that was one of the region’s primary products.

The pay followed Geneva Convention guidelines, 80 cents per day in canteen script, redeemable at the camp store for cigarettes, toiletries, and small luxuries.

Some prisoners saved their script, others spent freely, amazed at the availability of goods that had become impossible to obtain in Germany.

The evenings belonged to the prisoners.

After dinner, the hours until lights out were their own.

The camp offered recreational facilities that would have seemed generous for a vacation resort, let alone a prison.

A small library stocked with German language books, a recreation hall where prisoners organized their own entertainment, sports fields where soccer matches became regular events.

Some prisoners organized educational programs, teaching classes in languages, mathematics, or vocational skills to fellow inmates.

Others formed musical groups, performing German folk songs and popular melodies for appreciative audiences.

A few worked on craft projects, creating wood carvings and small items that they could send home or trade among themselves.

The camp administration encouraged these activities as beneficial to morale and order.

A welloccupied prisoner was a cooperative prisoner and at Pineer Grove Furnace cooperation was the norm rather than the exception.

A letter from a prisoner preserved in the National Archives describes the routine with evident wonder.

In the morning we work in the forest.

The work is hard but fair.

In the evening, we have time for ourselves to read, to play games, to talk with friends.

The food is more than I have seen in years.

Meat everyday, white bread, coffee.

I write these things, and I wonder if you will believe them.

Sometimes I do not believe them myself.

The prisoner added a line that military sensors apparently found innocuous, but that carried profound implications.

I think I am eating better here than my family is eating at home.

This thought brings me no joy.

The contrast between Pine Grove Furnace and what the prisoners had left behind was not merely material.

It was psychological, philosophical, almost spiritual.

These men had been raised in a Germany that promised strength through discipline, prosperity through sacrifice, victory through will.

They had been taught that the Reich was superior, that its systems were more efficient, that its people were destined to dominate.

And now they sat in an American prison camp, eating roast beef and white bread, working in beautiful forests, living in comfortable quarters, while their families in Germany scraped by on rationing and their cities burned under Allied bombs.

The abundance was an argument.

The comfort was a contradiction.

Everything they had believed was being quietly, persistently undermined, not through propaganda or lectures, but through the simple daily experience of living in a country that had more than enough.

The first Sunday at Pinerow Furnace brought an experience that Hinrich Vber would remember for the rest of his life.

Church services were offered at the camp, both Catholic and Protestant, conducted by chaplain who traveled between P facilities throughout the region.

Attendance was voluntary, but most prisoners chose to go, drawn by the familiarity of ritual, the comfort of worship in their native language, and the simple need for something that connected them to the lives they had known before the war.

The service was held in the camp’s recreation hall, wooden folding chairs arranged in rows before a simple altar.

The chaplain was a German American minister from Lancaster County, whose parents had immigrated from Bavaria decades earlier.

He spoke German with an accent the prisoners found both strange and comforting.

The old tongue filtered through American experience.

But it was the communion that shattered something in Weber.

The bread was white, soft, fresh baked that morning in the camp kitchen.

He had taken communion countless times before the war in the church where he had been baptized and confirmed.

But the bread had changed as Germany changed, growing darker, coarser, stretched with substitutes until it barely resembled bread at all.

Now he held a piece of white bread in his hands, the body of Christ rendered in American abundance, and he could not bring himself to eat it.

The chaplain noticed his hesitation.

After the service, he approached Vber quietly.

“Is something troubling you, son?” Vber looked at the minister.

“The bread,” he said.

“In Germany, we have not had bread like this for years.

My mother, my sisters, they have not tasted this in so long.” He paused.

And here they give it to prisoners, to enemies.

How can this be? The chaplain considered the question carefully.

Perhaps, he said, this is simply what we have.

Perhaps having enough means sharing even with those who were once enemies.

Weber did not reply, but he thought about the minister’s words for weeks afterward.

The abundance at Pinerove Furnace was not accidental.

The American policy toward German prisoners was shaped by multiple considerations.

Legal obligations under the Geneva Convention, practical needs for labor, and the calculation that well-treated prisoners would be less troublesome and more productive.

But there was also a strategic dimension that few prisoners fully understood at the time.

The war department’s special projects division had developed a program known as intellectual diversion activities, a euphemistic title for what was in essence a re-education effort.

The goal was to expose German prisoners to American values and American abundance to undermine the Nazi ideology that had shaped their worldview and to prepare them for eventual return to a democratic Germany.

The abundant food was part of this strategy.

So were the recreational facilities, the relative freedom of the camp, the overall treatment that emphasized the prisoners humanity rather than their enemy status.

A report from the Office of War Information dated October 1944 outlined the approach with bureaucratic clarity.

The prisoner who experiences American abundance firsthand is more likely to question the propaganda he was taught about American weakness and decadence.

Material conditions at well-administered camps serve as continuous demonstration of American productive capacity and social organization.

The prisoners were not being merely fed.

They were being educated through their stomachs, through their surroundings, through every meal that reminded them that the country they had been told was corrupt and declining had more than enough to share with its enemies.

The turning point for many prisoners came not through any single event, but through accumulation.

Day after day, the food kept coming.

Week after week, the treatment remained humane.

Month after month, the contrast between what they experienced and what they had been told grew impossible to ignore.

Some prisoners resisted the implications.

A core of committed Nazis maintained their ideology despite the evidence around them, organizing among themselves, intimidating fellow prisoners who showed signs of doubt.

The camp administration was aware of these dynamics and worked to identify and isolate the most committed ideologues.

But most prisoners found their certainties eroding.

Ernst Hoffman, a former university student who had been drafted in 1943, wrote in his camp journal about the process.

Every meal is an argument I cannot answer.

We were told the Americans were weak, that their society was rotten, that they could not sustain a war.

And yet here I eat meat every day while my professors in H Highidleberg live on bread and potatoes,” he continued.

“I do not know what to believe anymore, but I know what I see.

I know what I taste.

And these things do not match what I was taught.

” The news from Germany made the contrast more painful.

Prisoners were permitted to receive letters from home, censored, delayed, but eventually delivered.

The letters painted a picture of increasing desperation, food shortages, bombing raids, the slow collapse of everything familiar.

Weber received a letter from his mother in October 1944.

The sensors had blocked portions of it, but enough remained to understand the situation.

The rations have been reduced again.

Your sister trades her coffee substitute for bread when she can.

We stand in lines for hours, and sometimes there is nothing left when we reach the front.

I pray you are safe wherever you are.

I pray you have enough to eat.

He read the letter sitting on his bunk in a cottage that had once housed vacationers.

His stomach full of American roast beef, his hands still warm from holding a cup of real coffee.

The guilt was almost unbearable.

Some prisoners requested that their rations be reduced.

It was a gesture that the camp administration found touching but impractical.

Reducing rations for some prisoners would create inequality within the camp, potentially causing tension.

And there was no mechanism to redirect the saved food to German civilians.

The logistics were impossible and the military situation made any such transfer unrealistic.

The prisoners were told gently but firmly that their rations would remain as they were.

Eat, a guard told one prisoner who had made the request.

Your family would want you to survive.

That’s what you can do for them.

Survive this and go home when it’s over.

The prisoners ate.

They survived and they carried the weight of that survival with them.

Christmas 1944 brought the contrast into sharpest relief.

The camp kitchen prepared a feast that would have seemed extravagant in peace time.

Roast turkey with stuffing, mashed potatoes, vegetables, fresh bread, pumpkin pie for dessert.

The messaul was decorated with evergreen boughs cut from the surrounding forest.

A small tree stood in the corner, decorated with ornaments the prisoners had made themselves.

Some prisoners sang carols.

Others sat quietly, thinking of families far away.

A few wept openly, unable to reconcile the abundance before them with the hunger they knew their loved ones were experiencing.

Weber sat at a table near the window, looking out at the snow-covered mountains that surrounded the valley.

The scene was beautiful, peaceful, almost idyllic, nothing like the Christmas he had imagined when he was fighting in France, when survival itself seemed uncertain.

A guard passed by carrying a plate of extra turkey for anyone who wanted seconds.

“Merry Christmas,” the guard said.

Whoever looked at the young American soldier, probably his own age, probably with his own family far away, probably wishing he were somewhere else, too.

Merry Christmas, Veber replied.

For a moment, they were just two young men far from home sharing a holiday that meant the same thing in both their languages.

The war continued.

The camps remained.

The prisoners were still prisoners.

But in that moment, something human passed between them, something that the war had tried and failed to destroy.

The spring of 1945 came to Pinerove Furnace with a slow greening of the mountains.

The hardwood forests that surrounded the valley, bare through the long Pennsylvania winter, began to show the first pale colors of new growth.

The lake, frozen since December, thawed and returned to its deep blue reflection of the ridges above.

The trails that wound through Misho State Forest became passable again, and prisoners assigned to forestry work returned to the woods they had come to know during their months of captivity.

And the news from Europe grew more urgent with each passing week.

The Allied armies had crossed the Rine.

The Soviets were closing on Berlin from the east.

The Reich that had promised thousand-year dominion was collapsing in weeks, its cities in ruins, its armies in retreat, its population facing the final consequences of a war they had been told they could not lose.

The prisoners followed the news through official announcements and the American newspapers that were sometimes available in the camp library.

They watched as their homeland crumbled, felt the strange mixture of grief and relief that comes with the end of something terrible.

And on May 8th, 1945, they heard the news that the war in Europe was over.

The announcement came through the camp’s loudspeaker system.

Germany had surrendered unconditionally.

The fighting in Europe was finished.

The prisoners of Pinerove Furnace were now citizens of a defeated nation.

Their future uncertain, their past receding into history.

Hinrich Vber stood with a group of fellow prisoners in the compound listening to the American officer read the official statement.

Some men wept, some stood in stunned silence.

A few showed no visible reaction, their faces masks that revealed nothing of the turmoil beneath.

Weber looked around at the valley that had been his home for eight months, the stone buildings, the forested ridges, the lake shimmering in the spring sunshine.

He thought about the meals he had eaten here, the work he had done, the strange comfort he had found in a place that was by definition a prison.

He thought about his mother’s letter, about the hunger his family had endured while he ate roast beef and white bread.

He thought about the chaplain’s words regarding what it meant to have enough, and he thought about what kind of Germany he would return to if he returned, whenever he returned, and whether any of what he had learned here might matter in the ruins that awaited.

Repatriation from American P camps was a slow and complicated process.

The logistics of returning hundreds of thousands of prisoners to a devastated Europe challenged the Allied bureaucracies throughout 1945 and into 1946.

Prisoners classified as anti-Nazi were given priority, deemed suitable for helping to rebuild a democratic Germany.

Those with needed skills, doctors, engineers, administrators were sometimes retained longer, their labor still valuable in the post-war recovery.

Hinrich Vber was repatriated in the spring of 1946, nearly 2 years after his capture in France.

He returned to a Dusseldorf that was barely recognizable.

The apartment building where his family had lived had been destroyed in a bombing raid in late 1944.

His mother and one sister had survived, relocated to relatives in a small town outside the city.

His other sister had died not from bombing but from illness weakened by malnutrition and the stresses of the final war years.

The Germany he came home to was hungry, broken, occupied by the same forces that had fed him so well in Pennsylvania.

He searched for work, found it eventually in a factory that was slowly returning to production.

He married, he had children.

He lived the quiet life of a man who had seen enough of war and wanted only peace.

But he never forgot Pine Grove Furnace.

In the 1960s, Vber wrote a brief memoir for his grandchildren.

It was not published just a few handwritten pages in German describing his experiences as a soldier and prisoner.

Most of the pages dealt with the fighting in France, the fear and chaos of combat, the moment of surrender that had felt like failure at the time, but had probably saved his life.

But several pages were devoted to the camp in Pennsylvania.

We called it heaven, he wrote, not because we were happy we were prisoners far from home, not knowing if we would ever see our families again, but because for the first time in years, we had enough.

enough food, enough safety, enough of the simple things that the war had taken from us.

He continued, “I learned something there that I have never forgotten.

I learned that having enough is a kind of wealth that has nothing to do with money.

And I learned that sharing, even with your enemies, is a kind of strength that force can never match.” The memoir ended with a reflection on what the experience had meant to him.

The Americans did not have to feed us so well.

They did not have to treat us with such humanity.

The war had made us enemies, and enemies do not owe each other kindness, but they gave it anyway the food, the comfort, the dignity of being treated as men rather than monsters.

I think about this sometimes when people speak of strength and power.

The Reich promised strength through force, through conquest, through domination, but it could not feed its own people in the end.

The Americans fed their enemies.

That is a different kind of strength.

Perhaps a better kind.

Camp Piner Grove Furnace closed in 1946.

Its prisoners repatriated and its purpose ended.

The site returned to its pre-war function as part of Pennsylvania’s state park system.

The stone buildings that had served as camp headquarters became park facilities.

The cottages that had housed prisoners were eventually removed or repurposed.

The lake and forests remained, offering recreation to new generations who knew nothing of the German prisoners who had once worked among these trees.

Today, Pine Grove Furnace State Park draws visitors for hiking, camping, and fishing.

The Appalachian Trail passes through the park and hikers pause at the small store to purchase half gallons of ice cream in a tradition that has nothing to do with the war.

A few historical markers note that a PW camp once operated here.

The Cumberland County Historical Society maintains photographs and documents from the camp years.

Occasionally, researchers or descendants of former prisoners visit, seeking traces of the men who lived here during those strange months of captivity.

But for most visitors, the valley is simply beautiful, a peaceful place in the mountains, surrounded by forest, offering the simple pleasures of nature and fresh air.

They do not know about the white bread, the real coffee, the roast beef that made grown men weep.

They do not know that this place was once called heaven by men who had almost forgotten what enough felt like.

The mountains remain.

The forests still cover the ridges in waves of green that turn gold and red each autumn before fading to winter gray.

The lake still reflects the sky, unchanged since the prisoners first saw it 80 years ago.

The trails still wind through the woods, past trees that were saplings when Heinrich Weber walked these paths, now towering pillars of oak and maple and pine.

The prisoners are gone now.

The guards are gone.

The war that brought them together has faded into history.

Its survivors joining those who did not survive in the silence of memory.

But something remains in the archives, in the memoirs, in the oral histories passed down through families who remember.

A place where enemies were fed.

A time when abundance was shared.

A moment in history when the simple act of providing enough enough food, enough dignity, enough humanity became a form of power that outlasted all the violence of the war.

They called it heaven.

And in its own strange way, perhaps it