The truck stopped at the edge of the orchard, and no one came to unlock the tailgate.

August 1944.

The morning air hung thick with the sweetness of ripening fruit cherries past their peak, peaches coming on, the first apples beginning to blush on branches that sagged with abundance.

Dew still clung to the grass between the tree rows.

Bird song filled the spaces between leaves.

A farmhouse chimney released a thin ribbon of smoke into a sky so blue it seemed painted.

The German prisoners sat in the truck bed waiting.

They had learned to wait.

Waiting was the primary occupation of captivity, waiting for orders, waiting for meals, waiting for whatever came next.

They had been prisoners of the Americans for 3 months now, long enough to understand certain routines.

But this morning, the routine broke.

The driver, a young corporal from the motorpool, barely old enough to shave, walked around to the back of the truck.

He lowered the tailgate with a metallic clang that sent a flock of starings bursting from a nearby tree.

Then he gestured toward the orchard with casual indifference.

“Fruits that way,” he said.

“Farmer will show you what to pick.

Truck comes back at .” He walked back to the cab, climbed in, and drove away.

The prisoners stood in the settling dust, surrounded by 20 acres of fruit trees, and realized they were alone.

No guards, no rifles, no fences, nothing between them and the open Michigan countryside, but their own bewilderment.

A metallark called from somewhere in the tall grass beyond the orchard’s edge.

The sound seemed impossibly peaceful, impossibly free.

One prisoner, a corporal from Cologne named Derer, who had surrendered near Sherborg 6 weeks after D-Day, looked at his companions with an expression that mixed confusion with something approaching fear.

“This is a trap,” he said quietly in German.

“They’re testing us.” Another prisoner, older, a sergeant from the Eastern Front, who had seen things he never spoke of, shook his head slowly.

“No,” he said.

This is just America.

The orchard belonged to the Hoffman family, third generation fruit farmers whose greatgrandfather had planted the first trees in 1889.

The property sat outside Benton Harbor, Michigan, in the heart of what locals called the fruit belt, a stretch of southwestern Michigan, where the moderating influence of Lake Michigan created a microclimate perfect for cherries, peaches, apples, and grapes.

The war had created a crisis in this agricultural paradise.

Young men who should have been climbing ladders and filling bushell baskets were instead fighting in Italy, France, and the Pacific.

The Civilian Conservation Corps had been dissolved.

Migrant labor was scarce.

By the summer of 1944, fruit was rotting on trees across Berian County while farmers watched helplessly.

The solution came from an unexpected source.

German prisoners of war housed at branch camps throughout Michigan made available for agricultural labor under the terms of the Geneva Convention.

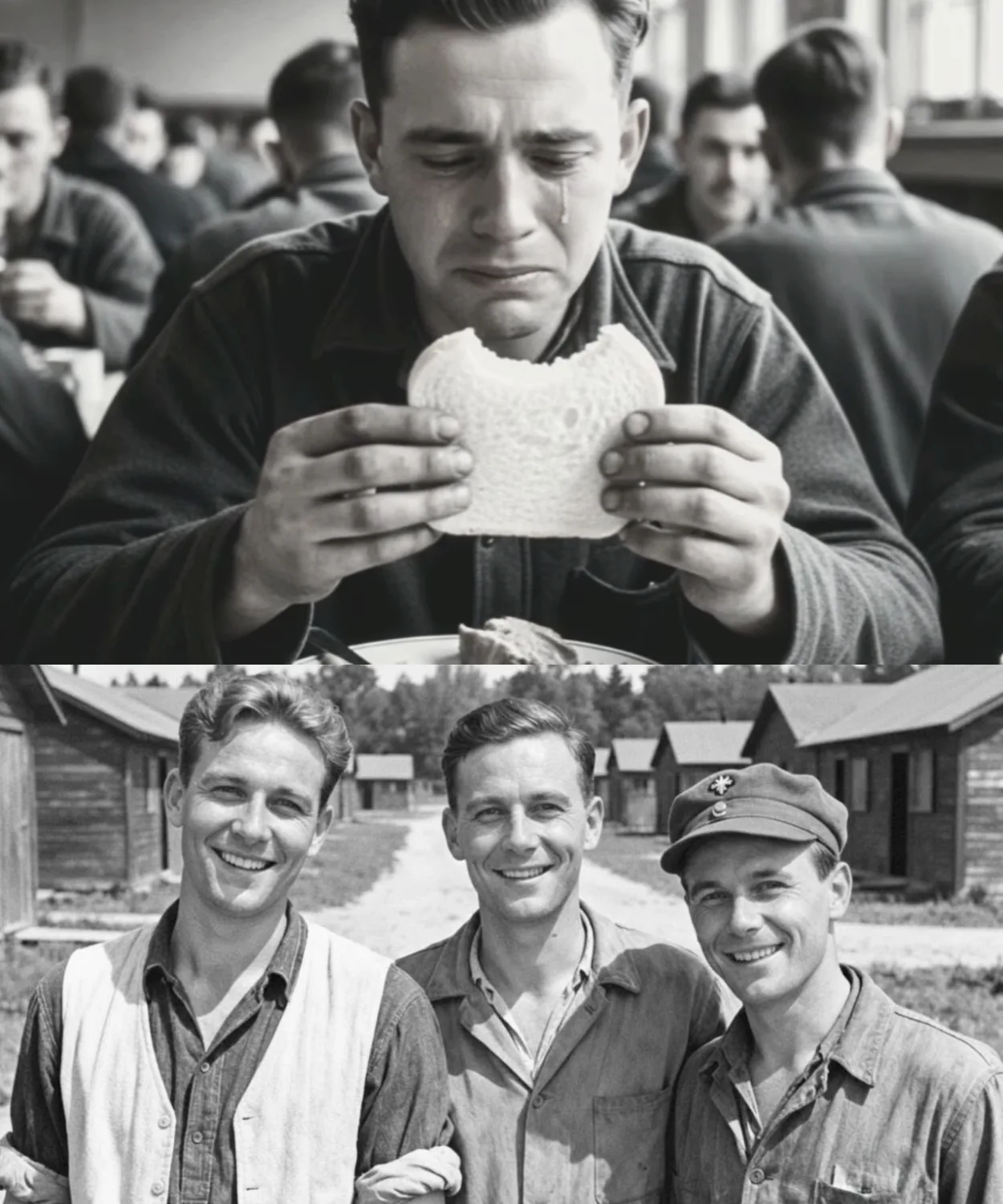

A photograph exists in the Michigan History Center archives taken in August 1944 near Benton Harbor.

The image shows a group of men in workcloth, no military insignia visible, standing beneath apple trees with picking bags slung over their shoulders.

Their faces show concentration, perhaps weariness.

One man in the background appears to be smiling at something outside the frame.

There are no guards visible, no weapons, no fences.

The photograph’s caption typed on an aging label reads simply p labor detail Hoffman Orchards Berian County 1944.

What the caption doesn’t explain what no brief label could capture is the profound psychological disorientation these men experienced when they discovered that their American capttors trusted them enough to work unguarded in the woods.

They had been told Americans were savage.

They had been told capture meant death or brutal labor.

They had been prepared for cruelty that would match or exceed what they knew happened on the Eastern Front.

Instead, they found orchards filled with ripening fruit, farmers who offered them water and sandwiches, and an honor system that assumed they would neither flee nor cause harm.

The assumption was almost never violated.

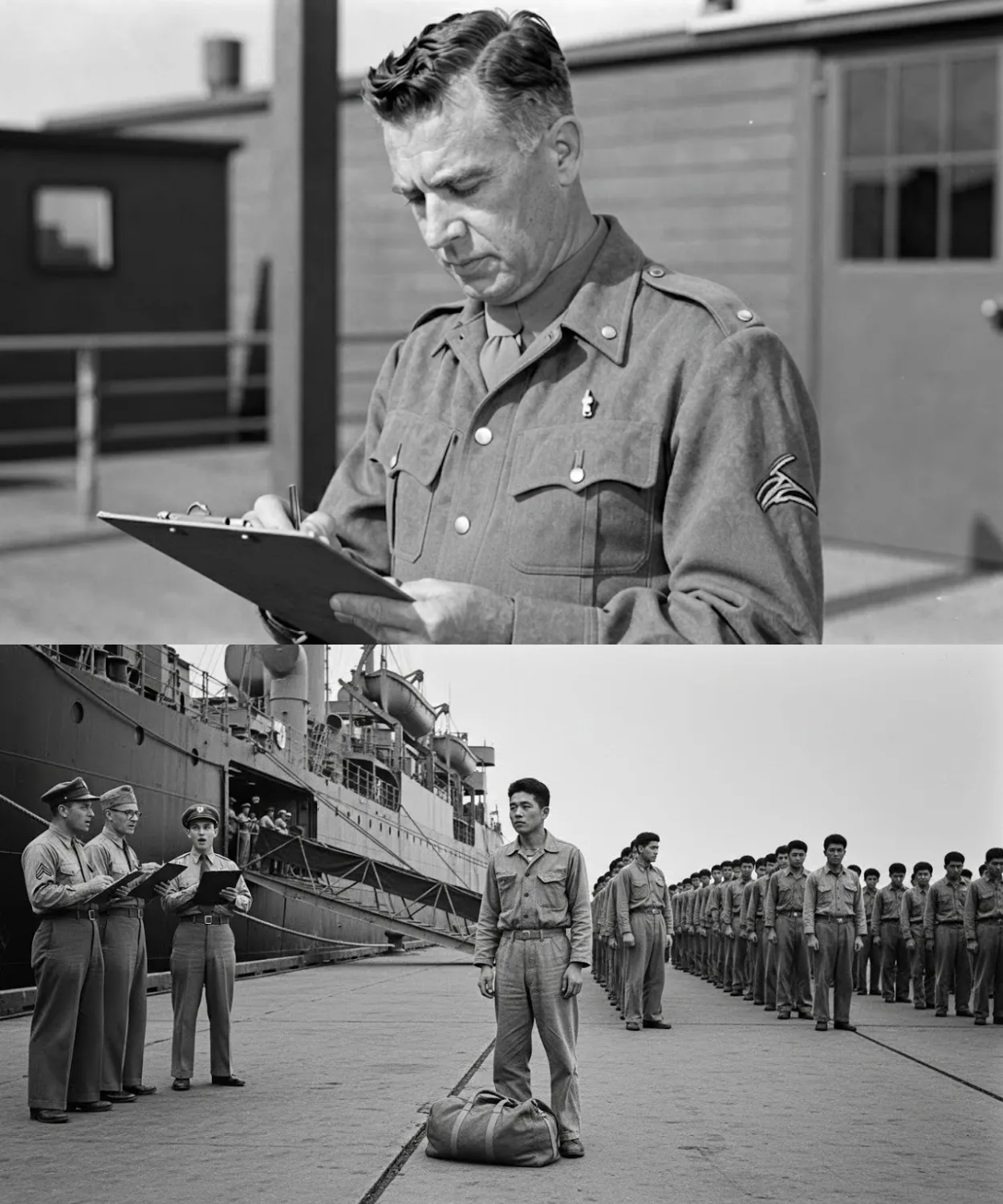

The prisoners assigned to agricultural labor in Berian County came primarily from Camp Kuster, a large military installation near Battle Creek that served as a base camp for thousands of German PSWs transported to Michigan after the Normandy campaign.

From Kuster, smaller groups were sent to branch camps throughout the state, temporary facilities established near areas of agricultural or industrial labor need.

The Benton Harbor area hosted several such branch camps during 1944 and 1945.

Small operations that housed anywhere from 50 to 200 prisoners at a time.

The camps were utilitarian wooden barracks, communal latrines, mess halls, recreation areas, but they were not prisons in the conventional sense.

The Geneva Convention required humane treatment, adequate food, and conditions comparable to those provided to rear echelon American troops.

Most camps met or exceeded these requirements.

A report from the Sixth Service Command dated June 1944 and preserved in National Archives Record Group 389 describes the labor arrangements with bureaucratic precision.

Prisoners of war shall be made available for agricultural employment in accordance with contracts established between the war department and local agricultural interests.

Prisoners shall be compensated at the rate of 80 cents per day in canteen script.

Security arrangements shall be determined by local command based on assessment of escape risk and prisoner cooperation.

That final phrase, security arrangements shall be determined by local command, created the flexibility that allowed the honor system to emerge.

Camp commanders quickly discovered that German prisoners assigned to fruit picking presented minimal escape risk.

Where would they go? The Michigan countryside offered no obvious sanctuary.

Prisoners spoke accented English at best.

Their faces were known in small communities where everyone knew everyone else.

And beyond the practical considerations, many prisoners simply had no desire to flee.

The war was going badly for Germany.

The camps offered safety, food, and work that was far preferable to combat or the brutal conditions they had heard about on the Eastern Front.

By midsummer 1944, commanders at several Michigan branch camps began experimenting with reduced security for agricultural details.

Armed guards were expensive.

Each guard assigned to orchard duty was a soldier unavailable for other tasks.

The prisoner’s behavior had been exemplary.

The math was simple.

The honor system was born from pragmatism, not idealism, but its effects transcended administrative convenience.

The daily routine for orchard labor followed a consistent pattern.

Prisoners rose at 0530, washed and dressed, ate breakfast in the camp mess hall.

By 0700, they assembled for work detail assignments.

Trucks arrived by and prisoners loaded without ceremony, no headcounts, no inspections, no warnings about escape attempts.

The journey to the orchards took between 15 minutes and an hour depending on which farm had requested labor that day.

The trucks were standard armyisssue olive drab canvas over wooden beds, the same vehicles that transported American soldiers to training exercises and supply runs.

The prisoners sat on wooden benches watching the Michigan landscape scroll past through gaps in the canvas.

What they saw was abundance.

Fields of corn standing head high in the August sun.

Dairy farms with fat cattle grazing in green pastures.

Farm wives hanging laundry in sideyards while children played.

Cars on the roads.

Private automobiles some of them knew carrying civilians about their ordinary business.

while a global war raged across two oceans.

A letter preserved in the Michigan History Center collection written by a prisoner named Helmet K in September 1944 describes these observations.

Every morning we pass through this countryside and every morning I see the same things farms that have never known bombing, children who have never hidden in shelters, women who go about their work without fear.

I compare this to what I know of Germany now.

The letters from home describing the raids and the shortages.

And I understand something I did not want to understand.

We were told America was weak.

We were told their people were soft and their land was chaotic.

But I have seen their land.

It is neither chaotic nor weak.

It is simply at peace even in war.

The farms that employed prisoner labor paid the war department a contracted rate typically around $3 per day per prisoner.

The prisoners themselves received their 80 cents in canteen script redeemable for tobacco, candy, toiletries, and small luxuries at camp stores.

The difference covered administrative costs and guard salaries, though the honor system reduced those expenses significantly.

The farmers themselves often provided additional compensation, not in money, which was forbidden, but in food.

Sandwiches appeared at midday.

Water and lemonade circulated during work breaks.

Sometimes at the end of a long day, a farm wife would press a sack of fresh fruit into a prisoner’s hands.

“Take these home,” she would say, using the word home to describe the barracks where enemy soldiers slept.

The work itself was demanding but not brutal.

Cherry-picking in July gave way to peach harvest in August, then apples through September and into October.

The prisoners learned to climb ladders balanced against narrow tree trunks to gauge ripeness by color and feel, to handle fruit gently enough that it reached the packing shed without bruises.

They worked alongside civilian laborers when available.

high school students earning summer money, elderly farmers too old for military service, occasional migrant workers who had found their way to Michigan’s fruit belt.

The prisoner crews kept to themselves initially, uncertain of their welcome, but the shared labor created gradual connection.

A prisoner might pass an apple to a farmer’s son.

A teenager might offer a cigarette during a break.

Words were exchanged, halting, simple, but human.

The farmers themselves remained cautious but practical.

They needed the labor.

The prisoners provided it.

Whatever the men had done before, whatever uniform they had worn, they were picking fruit now.

The peaches didn’t care about ideology.

Camp records from the summer of 1944 show remarkably few incidents.

No escapes from agricultural details in Berian County, no violence, no significant disciplinary problems.

The honor system born from necessity was holding.

The psychological transformation began in small moments that accumulated into larger shifts.

The first moment came on a morning in mid August when the work truck dropped a detail of eight prisoners at an orchard belonging to a farmer named Walter Steinberg.

The name itself caught their attention.

Clearly German in origin, perhaps second or third generation.

Steinberg met them at the edge of his property, a stocky man in his 50s with sunweathered skin and hands that showed decades of farmwork.

He looked at the prisoners for a long moment.

Then he spoke in slow, careful German, rusty but recognizable, the language of his grandparents preserved despite decades of American life.

Gooden Morgan Wilcom al-Manum Hof.

Good morning.

Welcome to my farm.

The prisoners stared.

One of them, a young soldier from Bavaria, recovered first.

Zishend Deutsch.

You speak German? Steinberg smiled.

a complicated expression that held memory and loss and something that might have been compassion.

My grandfather came from Bremen in 1872.

He planted these trees.

Well, his sons planted most of them, but he started it.

He paused.

I know this war is not simple.

I know you boys didn’t choose it, most of you.

So, we work today.

Yeah, just work.

He handed them picking bags and pointed toward the peach trees.

That evening in the barracks, the prisoners discussed what had happened with voices that mixed confusion with wonder.

“He treated us like hired hands,” one prisoner said.

“Not like enemies, not even like prisoners.

” “His grandfather was German,” another responded, “Perhaps he sees us differently.” The Bavarian soldier shook his head slowly.

“No, I think Americans simply see differently.

Period.” The second moment came during a sudden August thunderstorm that swept across Lake Michigan and struck the orchards without warning.

A detail of 12 prisoners was working deep in an apple orchard when the sky darkened and the first lightning flickered on the horizon.

The truck that had delivered them was miles away.

There was no shelter in the orchard itself, only trees that became dangerous in an electrical storm.

The farm’s owner, a woman named Margaret Holloway, whose husband was serving with the army in Italy, made an instant decision.

She ran to the orchard edge and shouted through the rising wind, “Come to the house, all of you, now.” The prisoners hesitated.

“Enter an American civilian’s home without guards, without permission, without lightning cracked overhead.” The hesitation ended.

They ran.

Margaret Holloway’s farmhouse was a modest two-story structure with a wide front porch and a kitchen that smelled of bread and coffee.

She ushered the prisoners inside 12 German soldiers dripping rainwater on her kitchen floor and began distributing towels from a hall closet.

Dry off, she said.

Storm should pass in 20 minutes.

Coffee’s on the stove.

Help yourselves.

She said it the way she might have spoken to her farm hands, to neighbors, to anyone who had been caught in the rain.

The prisoners stood frozen, unsure how to respond.

One prisoner, older than the others, a sergeant named Klouse, who had been a school teacher before the war, looked at the woman with an expression of profound bewilderment.

“Warum?” he asked softly, then caught himself and translated, “why, why do you help us?” Margaret Holloway paused in her distribution of towels.

She looked at the sergeant, really looked at him, and her expression shifted to something both weary and wise.

“Because you’re wet,” she said simply, “and the coffeey’s hot.

That’s enough reason, isn’t it?” The storm passed.

The prisoners returned to work.

But something had changed that could not be unchanged.

The third moment unfolded over time rather than in a single instant.

As the summer progressed, the prisoners began to encounter the same farmers repeatedly.

Relationships formed tentative, bounded by language and circumstance, but real.

Farmers learned prisoners names.

Prisoners learned which orchards had the best water, which farmwives baked the best bread, which farmers told the best jokes in fractured German English pigeon.

A report from the camp commander at Benton Harbor dated October 1944 and preserved in the Michigan History Center collection notes this development with evident surprise.

Prisoner morale has improved significantly since the implementation of agricultural labor details.

Several farmers have specifically requested the return of individual prisoners who demonstrated particular skill or reliability.

This phenomenon of name requesting was not anticipated but appears to benefit both labor efficiency and prisoner cooperation.

No security incidents have occurred in over 90 days of honor system operations.

The name requesting represented something unprecedented.

Farmers were beginning to see prisoners as individuals rather than an anonymous enemy labor force.

And the prisoners were beginning to see something equally significant about their capttors.

A letter from a prisoner named Friedrich written in September 1944 and later collected by the Michigan History Center describes this realization.

I think I am beginning to understand something about these Americans that I did not expect.

They do not guard us closely because they do not fear us.

They do not fear us because they are so confident of their own strength that a few hundred prisoners represent no threat whatsoever.

We could escape.

Some of us have discussed it.

But where would we go? We are surrounded by an entire nation that functions, that produces, that lives its life without the shortages and fear that consume Germany.

Their trust is not weakness.

It is the supreme confidence of a people who know they cannot lose.

The letter never directly addresses the war’s likely outcome.

It doesn’t need to.

The fourth moment came in late September as the apple harvest reached its peak.

A farmer named Thomas Anderson invited his prisoner work crew to join his family for a harvest supper, a tradition in Berian County that marked the end of the main picking season.

The invitation was unusual but not unprecedented.

Several farmers had begun, including prisoners, in minor celebrations, sharing food and rest at the end of long days.

The supper was held in Anderson’s barn, which had been swept clean and decorated with corn stalks and pumpkins.

Tables were assembled from saw horses and planks.

The farmer’s wife and daughters had prepared roast pork, mashed potatoes, fresh bread, apple pie, and cider pressed from the very fruit the prisoners had picked.

15 German prisoners sat at those tables alongside the Anderson family, neighboring farmers, and the few hired hands who had worked the harvest.

They ate together.

They raised glasses of cider together.

Someone produced a harmonica and played songs that transcended language, simple melodies that brought tentative smiles to faces on both sides of the long tables.

When the meal ended, Thomas Anderson stood and raised his glass one more time.

To the harvest, he said, to the work, to everyone who made it possible.

He paused, looking at the prisoners seated among his neighbors, and to the day when you can all go home, and we can go back to being ordinary folks who just happen to grow apples.

The prisoners did not fully understand every word, but they understood enough.

The war in Europe ended on May 8th, 1945.

But the prisoners labor continued through the summer harvest.

The peaches still needed picking.

The apples would come in September, regardless of what treaties had been signed in Rams and Berlin.

The atmosphere in the orchard shifted subtly after VE Day.

The tension that had always underlaid the honor system.

The awareness that these men were technically enemies began to dissolve.

Farmers spoke more freely.

Prisoners smiled more easily.

The work itself became almost companionable.

A photograph in the Berian County Historical Society collection dated August 1945 shows a group of German prisoners and American farm workers sitting together on the tailgate of a truck eating sandwiches.

One prisoner is offering an apple to a young American, perhaps 16 years old, who is reaching to accept it.

Both are laughing.

There is no way to determine from the photograph alone which figures are prisoners and which are free men.

That ambiguity was perhaps the point.

The repatriation process began in late 1945 and continued through 1946.

Prisoners were processed through separation centers, issued travel documents, and transported to ships bound for Europe.

Most pass through the orderly American system without incident, one final experience of efficiency and abundance before returning to a Germany they would scarcely recognize.

The farmers of Berian County returned to their usual patterns.

Migrant labor, family help, the occasional German American teenager earning money for college.

The orchards continued to produce.

The fruit belt continued to thrive.

Walter Steinberg, the farmer who had greeted prisoners in his grandfather’s German, lived until 1962.

His orchard remained in the family for another generation before being sold to a corporate agricultural operation in the 1980s.

His grandchildren still remember stories about the prisoners who picked fruit during the war, men their grandfather had treated with stubborn, deliberate humanity.

Margaret Holloway’s husband returned from Italy in 1946.

They farmed together for another 30 years, raising three children who would scatter across America as adults.

Margaret lived until 1987.

In her later years, she sometimes told the story of the thunderstorm, 12 German soldiers dripping rainwater in her kitchen, accepting coffee and towels while lightning cracked overhead.

They were just boys, she would say.

Wet boys who needed help.

That’s all anyone ever is really.

Thomas Anderson’s harvest suppers became legendary in Berian County, though the tradition faded after his death in 1958.

His greatgranddaughter, now a history professor at Michigan State University, has written about the 1944 supper in an academic journal documenting the moment when German prisoners and Michigan farmers shared a meal in a barn decorated with pumpkins and corn.

The prisoners themselves scattered across post-war Germany, carrying their experiences in the Michigan orchards into lives that no one could have predicted during the dark years of war.

Klouse, the former school teacher who had asked Margaret Holloway why and received her simple answer about wet men and hot coffee, returned to teaching in 1947.

He taught history and English at a gymnasium in Hamburgg for 31 years.

He is reported to have told students annually about his time in America, about orchards and trust and the strange country where enemies were given fruit to pick and coffee to drink.

Friedrich, whose letter described American confidence and German fear, immigrated to Argentina in 1952 and then to the United States in 1961.

He settled perhaps not coincidentally in Michigan where he worked as an accountant until his retirement.

He returned to Berian County once in 1978 and visited orchards that he recognized despite 34 years of change.

Deer the corporal from Cologne who had first believed the honor system was a trap remained in Germany and became a printer in Dusseldorf.

He never returned to America, but he named his first son, Thomas, after a farmer who had once raised a glass of cider and wished his enemies safe journey home.

The orchards of Barry and County still produce fruit.

The trees have been replanted many times, new varieties, new techniques, new generations of farmers adapting to changing markets and climates.

The specific trees that prisoners climbed in 1944 and 1945 are long gone.

Their wood returned to the earth, their fruit digested and forgotten.

But the land remembers what happened there, if land can remember anything.

The rhythm of seasons continues blossom and fruit harvest and dormcancy.

Workers still move through the rows in August and September, filling bags and crates with the abundance that the Michigan climate provides.

In the Michigan History Center in Lancing, the photographs and letters from the P program remain preserved in acid-free folders available to anyone curious enough to ask.

The images show men in workclo surrounded by fruit trees, their faces marked by the particular expression of those who have discovered something they did not expect.

They came as enemies.

They worked as laborers.

They left as witnesses.

They had learned something about America that propaganda could never teach something about trust, about confidence, about a nation so certain of itself that it could afford to be generous even to those who had been shooting at its sons and brothers just months before.

The orchards taught them, the coffee taught them, the unlocked tailgate taught them.

A meadow lark sings from the tall grass at the orchard’s edge.

The morning light falls golden through the leaves.

The fruit hangs heavy on the branches, waiting for hands to carry it home.

The harvest continues.

The lesson endures.