Texas, June 1944.

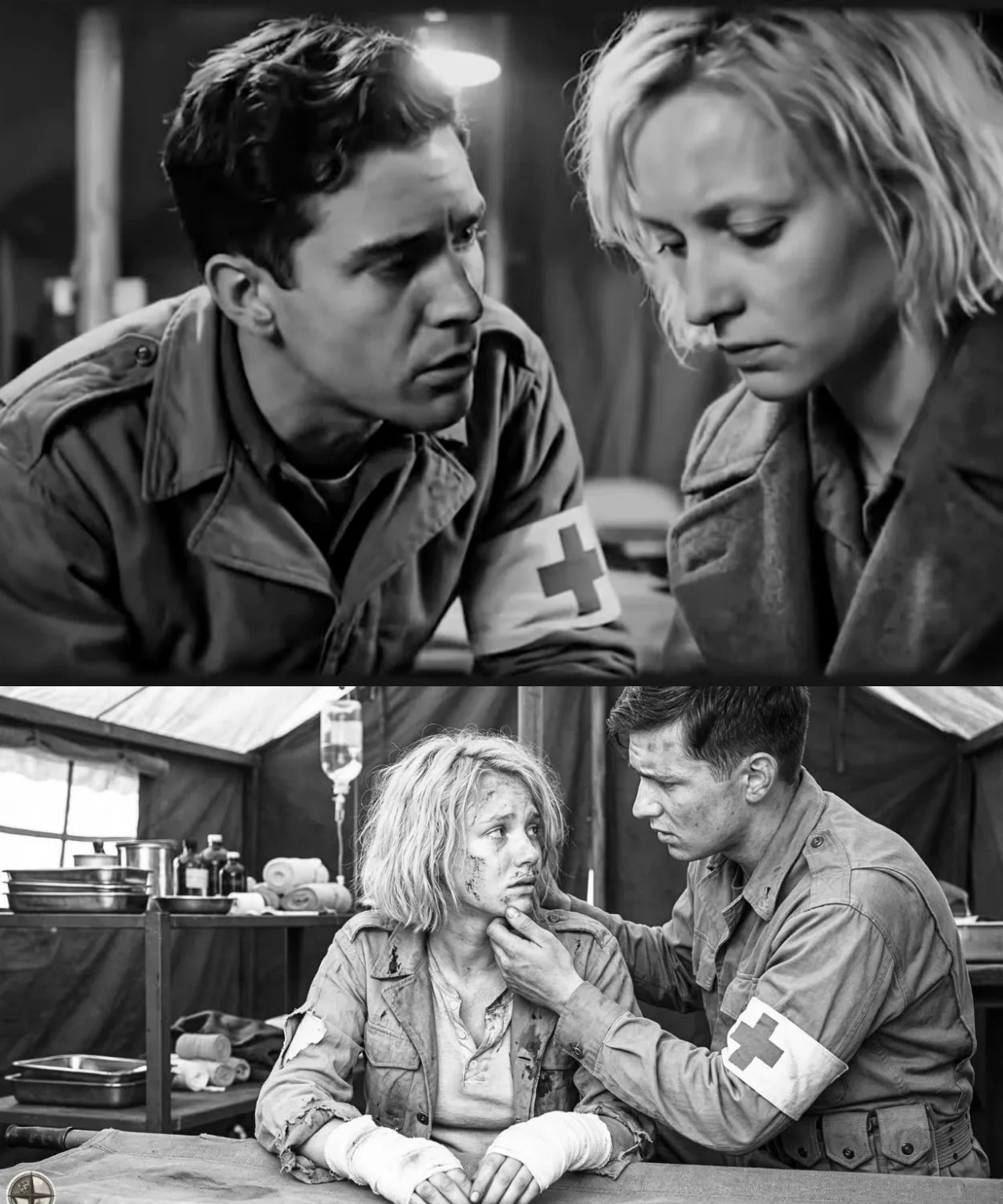

Captain Hinrich Vber stood in the bed of a military truck, his hands gripping the wooden slats as the vehicle bounced along a dirt road that seemed to lead nowhere.

The landscape stretched endlessly in every direction flat scrubblin broken only by mosquite trees and the occasional windmill turning slowly against a sky so blue it hurt to look at.

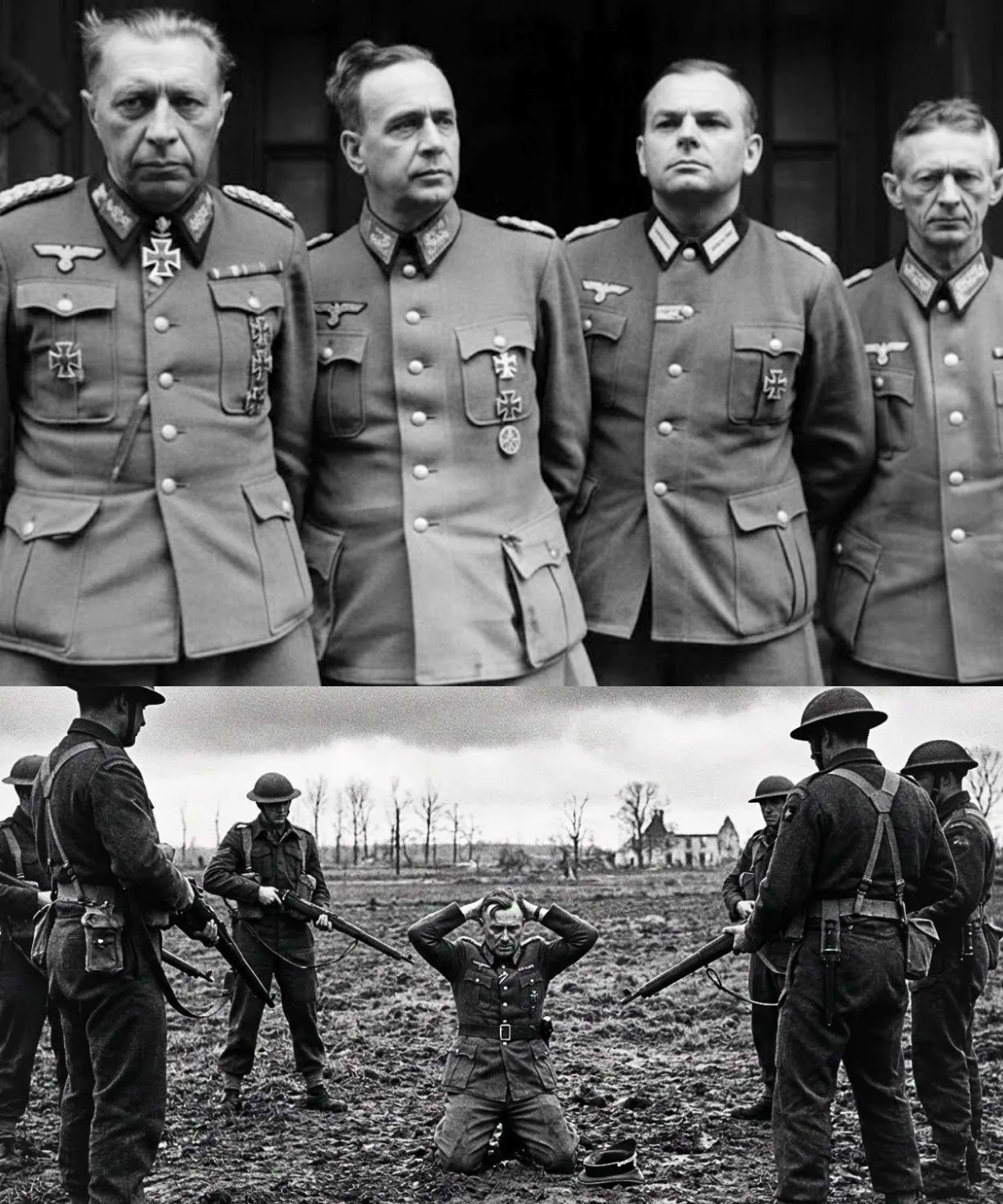

Behind him, 15 other German officers swayed with the truck’s motion, their faces tight with uncertainty.

They’d been told they were being assigned to a ranch for agricultural work, but Hinrich had seen the contempt in the guard’s eyes, had heard the word cowboys spoken with barely concealed amusement.

These Americans thought their prisoners would be humbled by primitive labor.

Degraded by association with what Heinrich considered the lowest form of frontier barbarism, he’d spent the 3-hour journey rehearsing his protests in careful English, preparing arguments about the Geneva Convention and proper treatment of officers.

But when the truck finally stopped and he saw the ranch sprawling before him, words failed.

Nothing in his Prussian military education had prepared him for this.

The ranch house was larger than Heinrich expected, a two-story structure of whitewashed wood with a wide porch that wrapped around three sides.

Beyond it, corrals and barns formed a complex of buildings that spoke of serious operation, not the crude homestead Hinrich had imagined.

Cattle dotted the distant pastures, hundreds of them moving like dark clouds against the pale grass, and everywhere the heat pressed down like a physical weight, different from any summer Heinrich had known in Germany, dry and relentless, making every breath feel like drawing fire into his lungs.

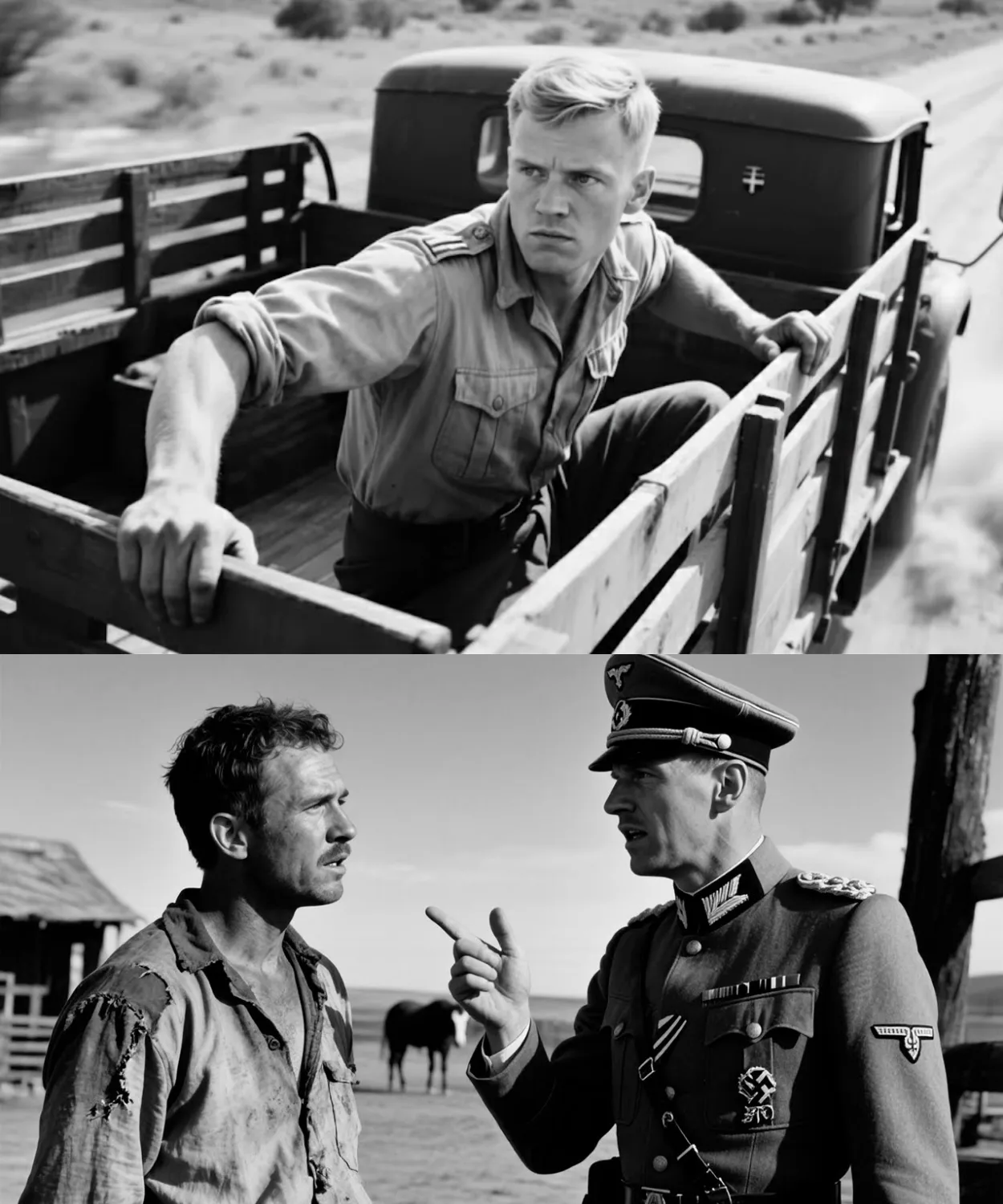

A man emerged from the ranch house as the truck’s engine died.

He was perhaps 50, weathered skin stretched tight over strong bones, wearing Genon trousers and a cotton shirt stained with honest sweat.

A hat shaded his eyes, but Hinrich could feel the assessment in his gaze as it swept over the German prisoners.

“Name’s Jack Morrison,” the rancher said, his voice carrying the lazy draw Heinrich had heard from Texas guards.

“This is the doublem ranch.

15,000 acres, 3,000 head of cattle, and more work than 10 men can handle properly.

He paused, seeming to measure his next words.

You gentlemen are here because I need help, and the military needs places to put prisoners.

Simple as that.

Hinrich stepped forward, drawing himself to full military bearing despite the heat and exhaustion.

Captain Hinrich Vber, Africa corpse.

I must protest this assignment.

Officers are not required under international law to perform manual labor.

Morrison studied him for a long moment, and Heinrich saw something shift in the man’s expression.

Not hostility exactly, but a kind of patient amusement that felt more insulting than anger would have been.

That so, Morrison said, “Well, Captain, here’s how things work on my ranch.

Every man pulls his weight, officer or not.

You’ll be fed three meals a day, given comfortable quarters, and treated fairly.

In exchange, he’ll help with the cattle, the fences, the daily work that keeps this place running.

You don’t like it, you can take it up with the military authorities.

He let that hang in the air, but they l just send you to a regular P camp where you l doing the same work with worse conditions.

The logic was inescapable, but Hinrich bristled at the casual dismissal of his rank and training.

I am an officer in the German military.

I have commanded men in combat.

I am not some, he searched for the English word, some peasant farmand.

No, Morrison agreed mildly.

You’re a prisoner who’s going to learn how to work cattle.

Whether you do it with grace or with bitterness is up to you.

The other prisoners had climbed down from the truck and stood watching this exchange with mixed expressions.

Some sympathetic to Hinrich’s s protest, others clearly too exhausted to care about pride.

A young lieutenant named Klouse stepped forward, his English halting but earnest.

Hair Morrison, we are grateful for food and shelter.

Please tell us what work you need.

Hinrich shot Klaus a sharp look, feeling the breach of military hierarchy, but Morrison was already nodding approvingly.

Good man.

Come on, all of you.

Let me show you where you’ll be staying, and we’ll get you something to eat before we start any work.

The prisoner quarters were in a converted bunk house behind the main barn, simple but clean, with real beds instead of the bunks Hinrich had endured in the temporary camps.

Each man was given a foot locker for personal items, a set of work clothes to replace their worn uniforms, and access to a washroom with actual running water.

After months of military detention, the relative comfort was unexpected, but Hinrich refused to be mllified.

As the other prisoners settled in, he stood at the bunk house window, staring out at the ranch operation, his mind cataloging everything he saw as evidence of American cultural inferiority, the casual way Morrison had addressed them, no acknowledgement of rank or military courtesy, the crude buildings and primitive equipment, the entire enterprise of cattle ranching, which seemed to Heinrich like playing at frontier life centuries after civilization should have moved.

beyond such things.

You are making this harder than it needs to be, Klouse said quietly in German, approaching Heinrich from behind.

We are prisoners.

We have no power here.

Why not accept what is offered? Because accepting means surrendering our dignity, Hinrich replied, still in German, his voice tight.

These cowboys, these frontier savages, they want to humiliate us by making us perform their crude labor.

I will not give them that satisfaction.

Or perhaps they simply need help with their ranch, and we are available workers.

Klaus shrugged.

Not everything is about humiliation, Hinrich.

Sometimes a fence is just a fence that needs mending.

Before Hinrich could respond, one of Morrison s ranch hands appeared at the bunk house door.

A younger man with sun bleached hair and a friendly expression.

“Supper’s ready when you are,” he called.

Come on up to the main house.

The dinner was served family style around a long table in the ranch house kitchen.

Morrison sat at the head, his wife Martha at the other end with the prisoners filling the spaces between.

The food was plentiful beef stew thick with vegetables.

Fresh bread still warm from the oven.

Coffee that actually tasted like coffee instead of the burnt substitutes Hinrich had been drinking for months.

Hinrich ate mechanically, barely tasting anything, hyper aware of the stranges of the situation.

In Germany, he’d been taught clear hierarchies, master and servant, officer and enlisted, conqueror and conquered.

But here at this table, those categories seemed to blur.

Morrison treated them neither as honored guests, nor as subjugated enemies, but as workers who would earn their keep and their respect through their actions.

Tomorrow we start early, Morrison said as the meal wound down.

Sunrise is around this time of year.

We’ll spend the morning checking fences in the south pasture and work on branding in the afternoon.

It’s hard work, especially in this heat, but you’ll get used to it.

What if we refuse? Hinrich heard himself ask, the words emerging before he could stop them.

Morrison’s expression didn’t change, but something cooled in his eyes.

Then you’ll be sent back to the military camp and someone else will take your place.

Your choice, Captain.

But I’ll tell you something.

I’ve had a lot of men work this ranch over the years, and the ones who fought the work were always the most miserable.

The ones who accepted it learned from it.

Those men usually found something valuable here.

Valuable? Hinrich couldn’t keep the scorn from his voice.

What could possibly be valuable about hurting cattle like primitive tribesmen? Martha Morrison spoke for the first time, her voice quiet but firm.

My grandfather drove cattle from here to Kansas in the 1870s.

3 months on the trail, sleeping under stars, facing stampedes and droughts and everything nature could throw at him.

He built this ranch with his own hands, raised a family, created something that’s lasted three generations.

You call that primitive, Captain Vber? I call it civilization.

The rebuke stung more than Hinrich wanted to admit, he finished his meal in silence, aware that he de made a poor first impression, but unable to soften his stance without, feeling like he de betrayed something essential about himself.

That night, lying in the darkness of the bunk house, Hinrich listened to the unfamiliar sounds of a Texas night cattle lowing in the distance, the wind rattling loose boards, somewhere a coyote’s lonely call.

He thought about his apartment in Munich, about restaurants and concert halls, and the ordered streets of a proper city.

He thought about his command in Africa, the clarity of military structure, the certainty of knowing his place in a defined hierarchy, and he wondered how he’d ended up here in this backwards frontier outpost, expected to perform labor he considered beneath his station.

The first week was misery.

The work began before sunrise and continued until dusk, with only brief breaks for meals.

Hinrich learned to mend fences, digging post holes in soil baked hard as stone, stretching barbed wire, till his hands blistered despite the gloves Morrison provided.

He learned to move cattle from one pasture to another, discovered that cows were far more stubborn and unpredictable than any recruit he’d ever commanded.

The heat was relentless.

By midm morning, sweat soaked through his shirt and ran in streams down his back.

The sun beat down with an intensity that made his head pound and his vision blur.

Several times in those first days, Hinrich felt close to collapse, but pride kept him upright, kept him working even when his body screamed for rest.

Morrison watched him with those patient, measuring eyes, offering advice that Hinrich struggled to accept.

Don’t fight the heat.

Work with it.

Move steady, not fast.

Drink water.

even when you’re not thirsty.

The land’s got its own rhythm.

You’ll all last longer if you match it instead of pushing against it.

But Heinrich pushed.

He attacked every task with grim determination, trying to prove through sheer force of will that he was above this work, that it couldn’t break him.

And every evening he returned to the bunk house exhausted and aching, his hands raw, his body screaming protest.

Klouse and several other prisoners adapted more quickly.

They learned to joke with Morrison’s ranch hands, picked up English phrases and cowboy slang, began to find their rhythm in the work.

Hinrich watched them with growing frustration, feeling like they were surrendering something important, accepting their captivity too readily.

“You should ease up,” Klaus told him one evening as Hinrich soaked his blistered hands in cold water.

You’re going to injure yourself working like this.

I will not be broken by cattle and fence posts, Hinrich replied through gritted teeth.

No one is trying to break you.

They’re just trying to run a ranch.

But Hinrich couldn’t accept that simple interpretation.

Everything felt like a test, a contest of wills between his Prussian military pride and this frontier.

American informality that refused to acknowledge the hierarchies Hinrich had spent his life learning to navigate.

The breakthrough came unexpectedly in the second week.

Morrison assigned Hinrich to help a ranch hand named Miguel break a young horse, a three-year-old stallion that had been running wild and needed to be trained for ranch work.

Hinrich protested that he knew nothing about horses, but Morrison just handed him a lead rope and said, “Then you’ll learn.” Miguel was patient, explaining each step in a mix of English and Spanish that Heinrich struggled to follow.

But the horse, a beautiful animal with a chestnut coat that gleamed like copper in the sun, responded to something beyond language.

Hinrich found himself drawn to the creature’s spirit, the way it tested boundaries without malice, the intelligence in its dark eyes.

“You are like me,” Heinrich found himself murmuring in German as he worked with the horse.

Captured, forced into service, you did not choose, trying to maintain dignity in impossible circumstances.

Miguel, who understood no German, just smiled and nodded.

But over the following days, as Hinrich spent hours working with the stallion, something shifted.

The horse began to trust him, began to respond to his voice and his touch, and Hinrich discovered a satisfaction he hadn’t expected, the pleasure of earning trust through patience and consistency, rather than through authority and command.

By the third week, Hinrich could ride the stallion around the corral.

The feeling of moving as one with the powerful animal, of communicating through subtle shifts of weight and pressure, stirred something in Heinrich he thought he’d lost.

Not joy exactly, but a kind of primal satisfaction that had nothing to do with rank or military hierarchy.

Morrison watched him work with the horse one evening, his expression thoughtful.

You have a gift for this, the rancher observed.

Natural horsemen.

Hinrich felt his habitual defensiveness rising, but something stopped it.

I rode as a child, he admitted.

In Bavaria, my uncle had an estate with horses.

But that was, he struggled to find the words.

That was different.

Formal riding, dress, not this working relationship.

This is honest riding, Morrison said.

No pretense, no show.

Just you and the horse figuring out how to work together.

That’s more valuable than any fancy maneuvers.

The comments settled into Hinrich’s mind like a seed, germinating slowly over the following days.

He began to notice things he’d dismissed before, the skill required to read cattle behavior, the knowledge needed to judge when a fence would hold.

Through a storm, the complex understanding of land and weather and animal nature that Morrison and his hands carried, these weren’t primitive skills.

Hinrich realized with dawning surprise.

They were sophisticated knowledge developed through generations of experience, different from his military training, but no less worthy of respect.

One morning in the fourth week, Hinrich found himself riding fence line with Morrison, checking for breaks after a violent thunderstorm the previous night.

The rain had turned the hard-baked earth temporarily soft, and the air smelled of wet sage and ozone.

They rode in comfortable silence.

Morrison on his familiar bay geling.

He Hinrich on the chestnut stallion he’d helped train.

“Can I ask you something, Captain?” Morrison said finally.

Hinrich tensed, expecting criticism or mockery.

“Yes, why are you fighting this so hard? The work, the ranch, all of it.

Most of your fellow prisoners seem to have found their peace with the situation.

But you’re still grinding against it like it’s an enemy to defeat.

The directness of the question startled Hinrich into honesty.

In Germany, I was educated to believe in proper order, proper hierarchy, officer and enlisted, educated and common, civilized and primitive.

coming here, being forced to perform manual labor, working alongside men who he stopped, aware he was about to say something insulting.

Men who what? Morrison’s voice was mild, but Heinrich heard the edge underneath.

Men who work with their hands? Men who didn’t attend militarymies.

Men who chose ranching over city life.

Men who seemed content with simple existence.

Hinrich finished carefully.

No culture, no refinement, just survival and work.

Morrison was quiet for a long moment, his eyes scanning the horizon.

When he spoke, his voice carried a weight Heinrich hadn’t heard before.

My grandfather was a rancher.

My father was a rancher.

I’m a rancher.

But my grandfather could read Latin and Greek.

Read them for pleasure in the evenings after 14 hours of hard work.

My father built the first school in this county, convinced the other ranchers to pull resources so their children could learn.

I studied agricultural science at Texas A and M learned soil chemistry and animal husbandry and business management.

My daughter is at university right now studying to be a veterinarian.

Hinrich felt heat rising in his face that had nothing to do with the sun.

You think we’re simple because we work with our hands, Morrison continued.

You think ranching is primitive because it involves cattle and horses instead of machines and factories.

But Captain, I’d suggest that building something that lasts for generations, that provides food for thousands of people, that teaches you to read weather and land and animal behavior, that’s not primitive.

That’s civilization at its most essential.

The rebuke was delivered without anger, which somehow made it cut deeper.

Hinrich had no response.

He rode in silence, the stallion moving smoothly beneath him, the vast Texas landscape stretching endlessly in all directions.

They found three fence breaks that morning, and Hinrich worked alongside Morrison to repair them without complaint.

The physical labor felt different, now not like a punishment or humiliation, but like necessary work that mattered.

Each post-driven, each wire stretched and secured, was a small act of maintaining order against entropy, of preserving what had been built through decades of effort.

That evening, as the prisoners gathered for dinner, Heinrich made a decision.

When the meal was served, he stood and cleared his throat.

The conversation quieted.

“I wish to apologize,” he said in careful English, looking at Morrison.

“I have been disrespectful.

I called your work primitive, your life univilized.

I was wrong.

I spoke from ignorance and arrogance.

You have shown us only kindness and fair treatment.

You have taught us valuable skills, and I have repaid this with contempt.

He paused, feeling the weight of the moment.

I am sorry, and I am grateful for the opportunity to learn from you.

The silence that followed felt heavy with surprised attention.

Then Morrison nodded slowly.

“Apology accepted, Captain.” “And I appreciate you saying it aloud,” he smiled slightly.

“Now sit down and eat before your stew gets cold.” The laughter that followed was gentle, breaking the tension.

Hinrich sat, feeling lighter than he had in weeks.

Across the table, Klaus caught his eye and nodded approvingly.

The transformation didn’t happen overnight, but it happened.

Hinrich began to engage with the work instead of resisting it, asking questions instead of enduring instruction in silent resentment.

He learned to rope calves, to judge a cow’s health from 30 yards away, to read the subtle signs that preceded a storm.

He learned to work leather and wood, to repair equipment that broke in the field, to make decisions quickly based on practical knowledge rather than theoretical training.

And slowly he began to understand what Morrison had tried to tell him.

Ranching wasn’t primitive.

It was complex, demanding intelligence and physical skill in equal measure.

The cowboys he’d scorned possessed knowledge that had taken lifetimes to accumulate.

Wisdom about land and animals and survival that no military academy could teach.

By the end of the second month, Hinrich had become one of the most skilled prisoners on the ranch.

Morrison began assigning him more complex tasks, trusting him to work independently to make judgments that affected the whole operation.

And Henrik found himself taking pride in this work, finding satisfaction in physical exhaustion.

It came from accomplishment rather than mere endurance.

One afternoon in late August, Hinrich was working in the south pasture when he spotted a cow in distress heavy with calf, clearly struggling with a difficult birth.

He remembered Miguel teaching him about such situations, the signs of breach presentation, the careful intervention sometimes necessary to save both mother and calf.

Hinrich dismounted and approached slowly, speaking in low German to calm the frightened animal.

She was in bad shape, her eyes rolling white with pain and fear.

Without hesitation, Hinrich stripped off his shirt, washed his hands and arms as best he could with water from his canteen, and carefully examined the cow.

The calf was positioned wrong, one leg folded back.

Left alone, both animals would die.

Hinrich had watched Miguel handle such situations twice, had listened to detailed explanations.

Now he put that knowledge into practice, working carefully to reposition the calf, using steady pressure and patience, speaking constantly to keep the cow as calm as possible.

It took 40 minutes of careful work before the calf finally emerged alive, breathing perfect.

The cow struggled to her feet and immediately began cleaning her baby.

Her distress forgotten in maternal instinct.

Hinrich sat back in the dust, his arms bloody to the elbows, sweat streaming down his face, and [snorts] felt something very close to joy.

Morrison found him there 20 minutes later, still sitting and watching the newborn calf take its first wobbling steps.

“Miguel saw you ride out here fast and sent me to check,” Morrison said, dismounting.

Then he saw the calf and smiled.

Breach birth folded leg.

I remembered what Miguel taught me.

You did good, Captain.

Real good.

Morrison extended his hand to help He Hinrich up.

That’s a valuable calf you saved.

And the cow’s one of my best breeders.

I’m in your debt.

Hinrich brushed dust from his pants, aware that he should feel degraded, covered in sweat and blood and dirt, having just performed work that would have been done by servants in his former life.

But instead he felt accomplished, useful, needed.

It is I who am in your debt, Hinrich said quietly.

For teaching me that honest work is not beneath any man’s dignity.

That there is worth in all labor done well.

Morrison nodded slowly.

You’ve learned the most important lesson this ranch has to teach.

Everything else is just details.

As summer turned to fall, Hinrich’s transformation became complete.

He no longer thought constantly about his life in Germany, no longer measured every experience against the standards of his military training.

He lived in the present, in the daily rhythm of ranch work, finding satisfaction in small accomplishments and hard-earned skills.

The other prisoners noticed and commented on the change.

Klouse remarked that Hinrich smiled now, actually smiled when making a difficult throw with a lasso or successfully completing a challenging task.

The rigid Prussian officer who’ arrived in June had become something different, still disciplined, still proud, but with a pride based on competence rather than rank.

In October, word came that some prisoners would be transferred to a facility near San Antonio, part of the ongoing reorganization as the war wound toward its inevitable conclusion.

Hinrich’s name was on the transfer list.

When Morrison told him, Hinrich felt a sharp pang of something like grief.

When do I leave? He asked.

2 weeks.

They’re sending trucks on the 15th.

Morrison paused.

You’re a good worker, Captain.

I’ll miss having you here.

That evening, Hinrich found himself sitting on the corral fence, watching the sunset, something he’d started doing regularly, finding peace in the vast western sky painted orange and purple and gold.

Klouse joined him, and they sat in companionable silence for several minutes.

“I don’t want to leave,” Hinrich said finally in German.

“I know.

I spent two months fighting this place, resenting every moment.

And now that I’ve finally learned to value it, to understand it, they’re taking me away.

That is the nature of war, Klaus observed.

We are not in control of our own lives.

We go where we are sent.

Do what we are ordered.

At least here for a brief time, we learn something valuable.

Hinrich thought about that.

What had he learned? Skills.

certainly practical knowledge about ranching and horses and the land, but something deeper, too.

He’d learned that his assumptions about civilization and culture were narrower than he’d imagined.

That there were ways of living and working that didn’t fit his rigid categories, but were no less worthy of respect.

And he’d learned something about himself that he was capable of change, of admitting error, of finding value in places he’d never thought to look.

The next two weeks passed too quickly.

Hinrich worked with desperate intensity, trying to absorb every remaining lesson to fix in his memory every detail of the ranch.

He spent extra time with the chestnut stallion, the horse that had first shown him how satisfaction could come from partnership rather than dominance.

On his final evening, Morrison invited him to dinner in the main house, just the two of them, a private farewell.

They ate steak and potatoes, drank real whiskey that Morrison produced from somewhere.

Talked about everything and nothing.

What will you do after the war? Morrison asked.

When you go home.

Heinrich had been thinking about that question constantly.

I don’t know.

My apartment in Munich is probably destroyed.

My military career is over.

Everything I built my life around is gone.

So build something new.

That is easier said than accomplished.

Morrison refilled their glasses.

Captain, these last few months I’ve watched you change.

You came here full of arrogance and resentment, convinced that you were too good for the work I was asking you to do.

But you learned.

You opened yourself to new possibilities.

That s the hardest thing any man can do.

Admit he was wrong and choose to grow rather than harden.

The war taught me I was wrong about many things,” Hinrich said quietly.

“The regime’s promises, the propaganda, the certainty that we were building something glorious.

All of it was lies.

But I didn’t know what to replace those certainties with.” Coming here, learning from you, showed me that there are other ways to measure worth, not by conquest or ideology, but by honest work and what you build with your own hands.

Then take that lesson home with you.

Germany is going to need rebuilding physically, yes, but also spiritually.

It’s going to need men who understand that there’s dignity in all honest work.

That civilization isn’t about dominating others, but about creating things of lasting value.

They talk late into the night.

Two men from vastly different worlds finding common ground in simple truths about work and worth and the possibility of redemption.

When Hinrich finally returned to the bunk house, he felt more at peace than he had since his capture.

The morning of departure arrived cold and clear.

Hinrich stood with his few possessions packed, watching the military trucks approached down the long ranch road.

Around him, the other prisoners being transferred said their goodbyes to Morrison and the ranch hands who deworked alongside them.

When Heinrich’s turn came, he found himself unable to speak.

Everything he wanted to say seemed inadequate gratitude for lessons learned, apology for wasted time, grief at leaving.

Morrison seemed to understand.

You’re welcome back here anytime, Captain,” the rancher said, gripping Hinrich’s hand firmly.

“After the war, if you ever find yourself in Texas again, you come to the M.

There’s always work for a good hand.

I would like that,” Hinrich managed.

Very much.

He climbed into the truck bed, settled among his fellow prisoners.

As the vehicle pulled away, Hinrich stood and watched the ranch recede into the distance.

The corral, the barns, the main house, the vast pastures stretching to the horizon, watched until it all disappeared, swallowed by the landscape.

But the lessons remained.

The understanding that worth came from work, that culture existed in places he’d never expected, that his rigid hierarchies had blinded him to valuable truths.

Those lessons would travel with him through the remaining months of his captivity, through the difficult years of German reconstruction, through the rest of his life.

The transfer facility near San Antonio was everything.

The ranch was not crowded, impersonal, focused on processing rather than productivity.

Hinrich endured it, but he felt the loss of the ranch acutely.

The other prisoners noticed his mood.

You miss the cowboy work, Klouse observed one evening.

I miss having purpose, Hinrich corrected.

I miss doing something that mattered, that had tangible results.

Here we just wait, marking time until someone decides what to do with us.

At least now you understand why I didn’t fight the ranch.

Assignment from the beginning, Klaus said with a slight smile.

Sometimes accepting what is offered leads to unexpected gifts.

Hinrich couldn’t argue with that.

He’d spent two months fighting before finally accepting, and those two months of resistance felt now like wasted time, opportunities lost to stubborn pride.

The war in Europe ended in May 1945.

News filtered slowly to the prisoner facilities Germany’s surrender, the regime’s collapse, the full revelation of the horrors that had been committed.

Hinrich listened to these reports with a sick sense of inevitability.

He’d suspected had heard rumors, but the full scope of the atrocities still shocked him.

In the processing cent’s barracks that night, arguments broke out among the prisoners.

Some refused to believe the reports, called them allied propaganda.

Others defended the regime’s ideology even in defeat.

Still others, like Heinrich, sat in stunned silence, trying to process the implications.

We served that, Klouse said quietly, sitting beside Hinrich.

We wore the uniform, followed the orders, fought for those aims.

We fought for Germany, Hinrich replied.

But the words felt hollow even as he spoke them.

Not for for they did.

Can we separate the two? That is the question we’ll spend the rest of our lives answering.

The repatriation came slowly, delayed by the chaos of postwar Europe.

Hinrich wasn’t sent home until October 1945, more than a year after his capture.

The ship crossing the Atlantic was crowded with prisoners.

All of them facing an uncertain future in a devastated homeland.

Heinrich stood at the rail, watching the American coast disappear.

Thinking about the ranch, about Morrison’s words, about the transformation he’d undergone in those months of captivity.

He was returning to a Germany he barely recognized to rebuild a life from ruins.

But he was returning with knowledge and skills he’d never expected to gain, with a perspective that might help him navigate the difficult years ahead.

Germany was worse than Heinrich had imagined.

Munich was rubble, his apartment destroyed, most of his possessions lost.

The physical devastation was matched by spiritual desolation.

A nation confronting the full horror of what had been done in its name.

Struggling to understand how civilization had produced such barbarism, Hinrich found work in reconstruction, using the practical skills he’d learned on the ranch.

He hauled rubble, repaired buildings, did honest labor with his hands.

And he found that the lessons Morrison had taught him applied here, too.

That there was dignity in rebuilding, satisfaction in creating something useful from destruction.

He also spoke when asked about his time in America, about the ranch, about learning that worth came from work rather than rank, about the generosity of former enemies who treated prisoners with respect.

Some people wanted to hear these stories, hungry for evidence that the world still held kindness and possibility.

Others rejected them, unable to accept that anything good could come from their defeat.

But Hinrich persisted.

He understood now that his small story of transformation was part of a larger story about how nations and individuals rebuilt themselves after catastrophic failure.

The lesson Morrison had taught him that honest work had inherent dignity, that civilization meant creating rather than destroying felt more relevant than ever.

In 1948, Hinrich received a letter forwarded through Red Cross channels.

It was from Morrison, written in the rancher’s careful hand.

Captain Vber, I hope this letter finds you alive and well.

We heard about the destruction in Germany, and I’ve thought of you often, wondering how you fared in the aftermath.

Things continue here much as always.

The ranch runs, cattle are born and sold, fences need mending.

Miguel speaks of you sometimes, remembers you as the German officer who learned to pull calves and wasn’t afraid to get his hands dirty.

High praise from Miguel, who doesn’t give compliments lightly.

The chestnut stallion you helped train is still here, still working.

Sometimes when I ride him, I think about those conversations we had about civilization and culture and what gives a man’s life meaning.

I like to think those talks meant as much to you as they did to me.

If you ever find yourself able to travel, the invitation stands.

There’s always room at the doublem for a man who knows the value of honest work.

Your friend Jack Morrison Hinrich read the letter until he could recite it from memory.

He wrote back immediately describing his life in postwar Germany, the challenges of reconstruction, the ways he’d applied the lessons learned on the ranch.

Thus began a correspondence that would continue for decades.

Two men from different worlds, maintaining friendship across distance and difference.

Hinrich never returned to the ranch.

The difficulties of international travel and the demands of rebuilding his life in Germany made it impossible.

But the memory of those months remained vivid, a touchstone he returned to in difficult moments.

When work felt degrading or purposeless, he remembered Morrison’s words about dignity in all honest labor.

When cultural certainties tempted him toward arrogance, he remembered his own humbling on the ranch.

He married in 1952, a widow who’d also survived the war’s devastation.

Together, they built a modest life.

No grand achievements, no return to his former status, just the quiet satisfaction of work done well, and relationships tended carefully.

Hinrich became a teacher, ironically, instructing young Germans about agriculture and animal husbandry, passing on the knowledge he’d gained in Texas.

And he told his story over and over to anyone who would listen.

The story of the Prussian officer who’d scorned cowboys as univilized only to discover that his own understanding of civilization was dangerously narrow.

The story of transformation that came from admitting error and opening himself to new ways of seeing.

Jack Morrison died in 1967 and Heinrich wept when the news reached him.

He never seen his friend again after that morning in 1944 when the military truck carried him away from the ranch.

But the friendship had endured through letters and memory.

Through the shared understanding of two men who drecognized something valuable in each other, despite all the forces that should have kept them apart, in Morrison’s will, Hinrich discovered he’d been left something.

A photograph of the chestnut stallion, now old but still magnificent, and a letter written shortly before Morrison’s death.

Captain Vber, if you’re reading this, I’m gone.

Strange to write to the future like this, but there are things I wanted you to know.

You asked me once in one of your letters why I bothered with you at all.

Why I didn’t just treat you as a prisoner to be managed.

Why I invested time in teaching you in breaking through your considerable stubbornness? The answer is simple.

I saw potential.

Beneath all that Prussian pride and those rigid certainties, I saw a man capable of growth, of change, of becoming something better than what he’d been taught to be.

And I believe that helping you make that transformation might matter, might ripple outward in ways I couldn’t predict.

From your letters over the years, I think maybe I was right.

You’ve taught others what you learned here.

You’ve lived a life of honest work and genuine humility.

You’ve proven that redemption is possible, that men can change even after profound error.

That matters more than you know.

The world needs men who’ve learned those lessons.

Who can teach younger generations that strength comes from admitting weakness? That wisdom begins with acknowledging ignorance.

Thank you for the friendship.

Thank you for proving that the effort wasn’t wasted.

Your friend always, Jack Morrison.

Hinrich kept that letter with the photograph, two tangible reminders of the transformation that had begun on a Texas ranch in 1944.

And in his final years, when students asked him about the war, about survival and rebuilding, he would pull out that photograph and tell them about the chestnut stallion, about the rancher who’d seen past his arrogance, about the painful lesson that civilization existed in places he’d never thought to look.

I came to that ranch thinking cowboys were univilized, he would say.

I left knowing that I was the barbarian, not in cruelty, but in my narrowness of vision.

War had taught me to see in categories, in hierarchies of worth.

The ranch taught me to see in truth, and that truth was uncomfortable but necessary, that honest work is never beneath anyone, that wisdom exists in unexpected places, that redemption begins with admitting error.

The students would listen, trying to understand how a German officer had learned crucial lessons from American cowboys, how enemies had become friends, how defeat had led to growth rather than bitterness.

And Hinrich would smile, remembering heat and dust and the endless Texas sky, remembering the chestnut stallion and Morrison’s patient instruction, remembering the moment he’d finally stopped fighting and started learning.

I begged to stay on that ranch.

he would conclude.

When they told me I was being transferred, I actually asked if there was any way to remain.

The officer in me was horrified, begging to continue work I’d once considered beneath me.

But the man I’d become understood that I’d found something valuable there, something worth preserving.

I didn’t get to stay, of course, but what I learned there stayed with me, and that in the end was enough.

Texas, June 1944.

A proud Prussian officer stepping off a truck, ready to defend his dignity against degrading labor.

Texas, October 1944.

That same man watching the ranch disappear behind him.

Griefstricken at leaving, forever changed by what he’d learned.

A transformation hadn’t come easily or quickly.

It had required humility and pain, required Hinrich to dismantle certainties he’d spent a lifetime building.

But it had been real.

And in the devastated landscape of postwar Germany, in the difficult work of rebuilding both nation and self, those lessons proved essential.

Civilization, Hinrich learned, wasn’t about conquest or culture in the narrow sense.

It was about building things that lasted, about treating others with dignity, about finding worth in work and wisdom in unexpected teachers.

The cowboys he descri, that true strength came from admitting weakness.

That growth required letting go of pride, that redemption was always possible for those willing to do the difficult work of change.

And so the story ended where it began in the dust and heat of a Texas ranch where a German officer learned that everything he believed about civilization was wrong and in being wrong found the possibility of becoming something Better.