May 1945, northwest Germany.

The war in Europe was over, but Captain James Stone stood in the ruins of a small German town, and knew the real nightmare was just beginning.

Around him stretched endless piles of broken brick and twisted metal.

The smell of smoke still hung in the air, mixing with something worse, something he tried not to think about.

his boots crunched on shattered glass as he walked through what used to be the main street.

28 years old, a high school history teacher from rural Ontario just 3 years ago.

And now he commanded 120 exhausted Canadian soldiers responsible for 15,000 German civilians who looked at him with hollow, desperate eyes.

The numbers painted a picture darker than the bombed out buildings.

Across Germany, 7 million people wandered the roads with nowhere to go.

20% of all homes had been turned into rubble.

The Canadian army alone held 400,000 German prisoners, and nobody knew what to do with them.

Stone had received his orders that morning, typed on crisp paper that seemed to mock the chaos around him.

Establish military control.

Prevent resistance.

No fraternization with German civilians.

Treat all Germans as potential threats.

Simple words that made no sense when you stood in a town where hungry children dug through garbage and old women carried buckets of water from a contaminated well because the pumps didn’t work.

The British sector to the west was already falling apart.

Stone had heard the reports.

riots over food, black market gangs controlling whole neighborhoods, German civilians refusing to cooperate.

And why would they? The Allied military government tried to run everything themselves, giving orders in English that nobody understood, making rules that ignored how things actually worked.

It took 300 British soldiers to control a town the same size as Stones.

And they still had fights breaking out every single day.

The Americans weren’t doing much better.

They brought in their own administrators, treated the Germans like children who couldn’t be trusted to do anything, and ended up drowning in paperwork while people starved in the streets.

Intelligence officers predicted things would get worse, much worse.

They warned about werewolf fighters, Nazi loyalists, who would fade into the population and strike from the shadows.

50,000 Allied soldiers might die, they said, fighting an enemy they couldn’t see in a country they didn’t understand.

Stone looked at his men, saw how tired they were, how much they wanted to go home, and wondered how they were supposed to fight ghosts while also feeding thousands of people and keeping the lights on.

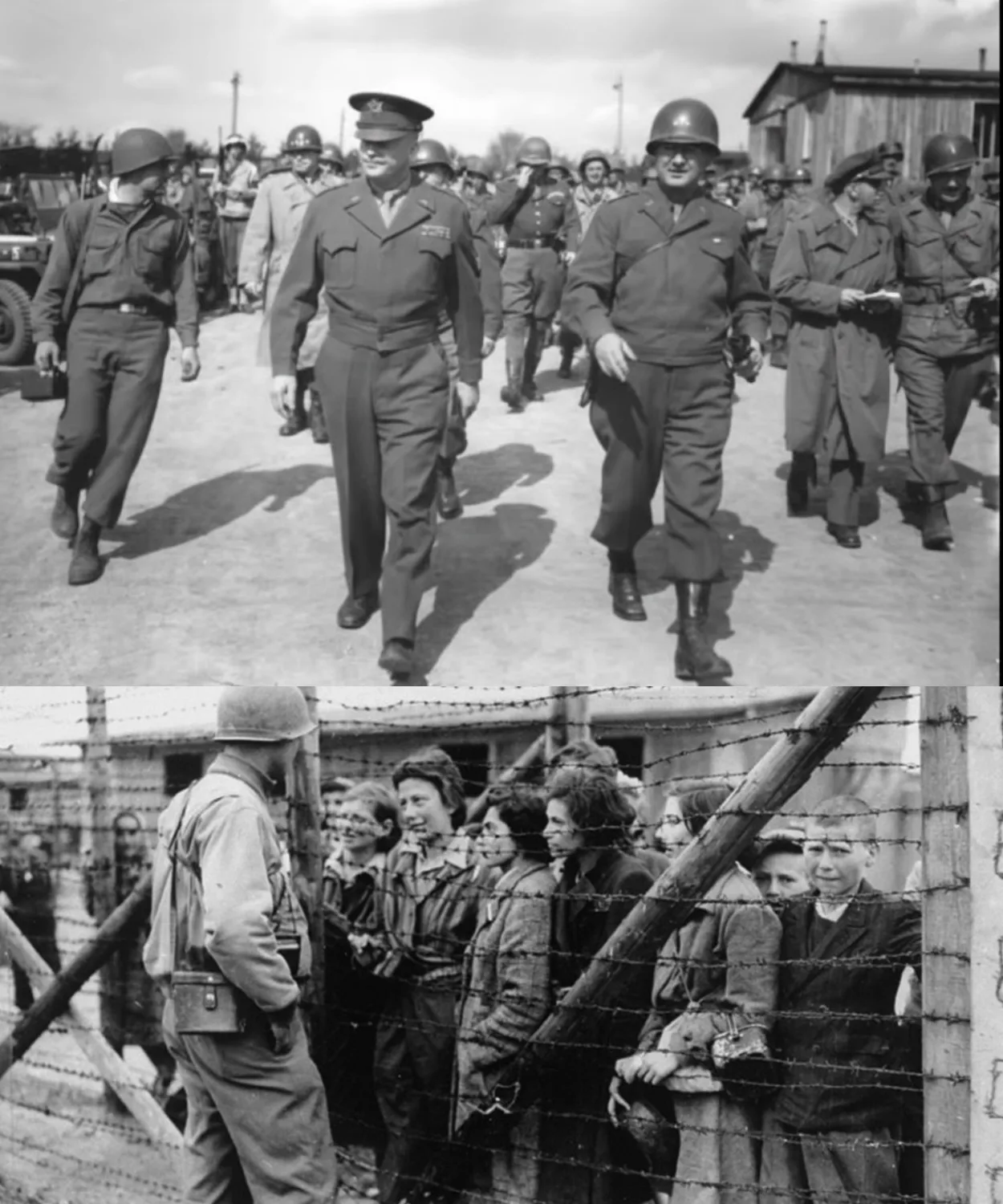

Then they captured General Heinrich Voss.

He was 56 years old, a career officer who had served in the German military for 33 years.

They found him in a farmhouse on the edge of town, wearing a clean uniform, waiting calmly with his hands visible.

He didn’t run.

He didn’t fight.

He simply stood up, saluted, and surrendered with the dignity of a man who knew the war was over.

Stone sergeant wanted to ship him off to the prisoner camp immediately, process him like all the others, lock him away where he couldn’t cause trouble.

The farmhouse belonged to a local widow who’d given Vos shelter in his final days of freedom.

She stood in the doorway, trembling, expecting the Canadians to punish her for harboring an enemy officer.

But Voss had already prepared a written statement in careful English, explaining that he’d commandeered her home and that she’d had no choice.

He handed it to Stone without being asked.

It was a small gesture protecting a civilian from consequences, but it told Stone something important.

This man still thought about his responsibilities to others, even in defeat.

Stone sergeant wanted to ship him off to the prisoner camp immediately, process him like all the others, lock him away where he couldn’t cause trouble.

But something made Stone pause.

He watched as German officials, the ones who had stayed behind when the Nazi leadership fled, approached the general with obvious respect.

The town’s former deputy mayor, an old man with thin white hair, actually bowed slightly when he saw Voss.

The police chief, stripped of his weapons and authority, stood straighter when the general looked at him.

These weren’t the reactions of people greeting a defeated enemy.

These were people recognizing someone they still trusted, someone who still had authority in their minds even though his army had surrendered.

Stone had studied history.

He knew about the chaos after the First World War, how Germany had collapsed into riots and revolution, how the old order vanished and left nothing but angry mobs and desperate people.

He could see the same thing starting to happen now.

The Nazi government was gone, wiped away like it had never existed.

But the people remained and they needed food, water, shelter, and someone to tell them what to do next.

The Allied plan was to do it all themselves.

To treat every German as a potential Nazi.

To trust nobody and control everything.

It was clean.

It was clear.

It was safe.

It was also impossible.

Stone did the math in his head.

12 soldiers, 15,000 civilians, plus 3,000 refugees who had stumbled into town from somewhere else.

His men were spread so thin they could barely patrol the streets.

How were they supposed to organize food distribution, fix the water system, get the hospital running, clear the roads, stop the black market, prevent crime? They didn’t speak German.

They didn’t know which buildings were important.

They didn’t understand how anything worked.

They could give orders all day long, but who would actually do the work? He looked at General Voss again, standing straight despite his surrender, watching the town with the eyes of someone who understood systems and organization.

Stone thought about his orders, about the non-fratonization policy, about everything he’d been told.

Then he thought about the alternative, about what would happen if this town fell apart like the British sectors, about his men trying to do everything themselves, while people starved and chaos spread.

A crazy idea formed in his mind, every rule said it was wrong.

Every regulation forbade it.

His superiors would be furious.

But standing there in the ruins, watching German civilians haul water in buckets while his own men stood guard with rifles, Stone wondered if maybe the rules were the problem.

He thought about his classroom back in Ontario about teaching teenagers that history was made by people who questioned the obvious answers.

He’d told them about leaders who succeeded by doing what everyone said was impossible.

Now he stood in the rubble of a defeated nation, holding the power to either repeat history’s mistakes or write a different chapter.

The choice felt enormous.

Trust a Nazi general to help rebuild Germany or watch thousands starve while his exhausted soldiers tried to do the impossible alone.

Both options terrified him.

But only one might actually work.

What if instead of working around the Germans, they worked through them? What if the very people everyone said couldn’t be trusted were actually the only ones who could make this work? What if that defeated general, standing calmly in the rubble of his country, held the key to preventing the disaster everyone predicted? He called the general into what used to be the town hall, a building with half its roof missing and broken windows that let in the cold spring air.

Through a translator, Stone laid out his proposal.

The general would serve as a liaison between the Canadian forces and the German civilian administration.

He would coordinate the German officials who remained, organize work crews, help restore basic services.

In exchange, he would stay in town rather than going to a prisoner camp.

Boss listened without expression, then asked a single question.

Did Stone have the authority to make this arrangement? Stone admitted he probably didn’t.

The general nodded slowly, understanding the risk they both were taking, and agreed.

Before leaving the town hall, Voss paused at the doorway.

Through the translator, he said something that caught Stone offguard.

Captain, I have spent 33 years following orders.

Some of those orders led to terrible things.

I cannot undo what has been done.

But if you give me this chance, I will spend whatever time remains proving that not every German soldier forgot how to serve honorably.

Stone didn’t know how to respond to that.

The translator looked uncomfortable, uncertain whether he should have shared such personal words.

Stone finally nodded and said, “Then let’s start tomorrow.” It wasn’t forgiveness.

It wasn’t friendship, but it was acknowledgment that maybe, just maybe, redemption was possible, even in the ruins of a war neither side could take back.

Within 48 hours of his capture in early May 1945, General Voss was holding meetings with German administrators in a basement room lit by candles.

Stone assigned two soldiers to watch every meeting.

Men who didn’t speak German, but could see who came and went.

The general’s first task was simple but crucial.

The town had 15,000 civilians and 3,000 refugees, and nobody knew where the food was or how to distribute it.

Under the Nazi system, everything had been controlled from Berlin.

Now Berlin was a smoking ruin, and the control was gone.

But somewhere in warehouses and storage rooms, supplies existed.

Voss knew how to find them because he understood how the German system worked.

Within 3 days, Voss organized 200 volunteers to clear the main roads, identified which power lines could be repaired, and restored electricity to the hospital and water pumping station.

Stone stood in the hospital as lights flickered on for the first time in weeks and heard a German nurse start crying with relief.

Stone watched as doctors and patients reacted to the lights.

An elderly man in a hospital bed reached up toward the ceiling bulb as if touching something sacred.

A young mother clutched her sick child tighter, whispering prayers of thanks.

The hospital staff immediately began moving patients who’d been waiting in dark corners into proper examination rooms.

Within minutes, a surgery that had been postponed for days began in the operating theater.

This wasn’t just electricity returning.

It was hope coming back.

Stone realized that every hour without power had meant suffering he couldn’t measure.

And General Voss had restored it in 72 hours.

The results kept coming.

Within the first week, black market activity dropped by more than half.

It turned out the general knew exactly who was running the illegal operations because he’d been watching the same people for years.

A quiet word from Voss, backed by Canadian authority, shut down operations.

That stone soldiers hadn’t even known existed.

The local German police, disarmed but still wearing their uniforms, started patrolling again under Canadian supervision.

They knew the town, knew the troublemakers, knew which sellers people were hiding things in.

Stone’s men didn’t have to be everywhere at once anymore.

They could focus on oversight while Germans handled the daily details.

Then the message came from British command.

Stone’s superior officer arrived in a jeep, his face read with anger, carrying orders typed on official paper.

cease all fraternization immediately.

The general was to be transported to a standard prisoner of war camp.

The arrangement violated every regulation about dealing with captured enemy officers.

A formal investigation would determine if Stone had exceeded his authority.

The officer looked around the functioning town, saw German workers rebuilding under Canadian supervision, saw the general coordinating with civilian officials, and his expression made clear what he thought.

This looked like collaboration with the enemy.

Stone tried to explain the results.

Zero Canadian casualties.

Food distribution working smoothly.

18,000 people being fed with no riots.

hospital treating 200 patients every day.

All utilities operational.

He needed only 15 soldiers now for ongoing supervision instead of the original 120.

The rest could be reassigned to other duties.

His superior officer wasn’t impressed.

Results didn’t matter if the methods violated policy.

Orders were orders.

The arrangement would end immediately.

For 72 tense hours, Stone thought his military career was over.

His men would be scattered.

The system they’d built would collapse.

The town would slide back into chaos, and he’d face disciplinary action for doing something that actually worked.

Stone spent those three days documenting everything.

He wrote detailed reports on food distribution, utilities restoration, crime statistics, troop deployment ratios.

He interviewed his soldiers, recorded testimonies from German officials, photographed the functioning town square.

If they were going to shut him down, he wanted proof that his method worked.

General Voss noticed the frantic documentation and asked through the translator if this was the end.

Stone admitted he didn’t know.

Voss nodded slowly and said something in German the translator struggled with.

Finally, the young private found the words.

Then we make these three days count for something.

They worked harder than ever, knowing each accomplishment might be their last together.

Then Brigadier William Foster arrived.

Foster was a pragmatic officer who’d spent the entire war solving impossible problems with limited resources.

He’d heard about Stone’s experiment and wanted to see it himself before making a final decision.

Foster spent two days in the town.

He talked to Stone soldiers and found them rested, confident, no longer stretched to the breaking point.

He observed the general coordinating work crews and saw efficient organization, not secret Nazi plotting.

He interviewed German civilians who spoke broken English.

One elderly woman told him, “First time since war, I sleep without fear.” A former shopkeeper said, “The Canadian captain, he sees us as people, not monsters.” Foster visited the adjacent British controlled town similar in size and found 300 troops struggling to maintain martial law with daily incidents.

British soldiers looked exhausted, angry, trapped in a situation with no end in sight.

The contrast was impossible to ignore.

He did the math.

If Stone’s method could be replicated, thousands of soldiers could be freed up for other duties.

the Canadian Army could control more territory with fewer men and less violence.

Foster took a career risk.

He filed a report praising Stone’s approach and requesting an official exception to the non-fratonization policy.

He argued that pragmatism in the field should outweigh rigid doctrine from headquarters.

He personally vouched for Stone’s judgment and shielded him from the disciplinary action that seemed certain.

The response took 3 weeks.

During that time, Stone and Voss continued their work, not knowing if each day would be their last working together.

The official reply, when it came, was cautious but positive.

Stone could continue his experiment on a trial basis.

results would be monitored closely.

Any sign of German resistance or abuse of trust would end the program immediately.

It wasn’t enthusiastic approval, but it was permission.

Stone read the message twice, barely believing it, then walked to the basement room where Voss was meeting with the town’s engineers about repairing the bridge over the river.

After 3 weeks of operation, the town wasn’t just stable.

It was thriving in ways Stone hadn’t imagined.

Food rations reached all 18,000 people with zero riots.

The hospital functioned at full capacity.

The water system served the entire town.

German workers had cleared most of the major rubble.

A handwritten sign in the town square in both German and English listed work opportunities and where to report.

Children played in streets that had been swept clean.

The strange peace felt almost normal, except for the sight of Canadian soldiers drinking coffee alongside German workers, exchanging smiles even when they couldn’t exchange words.

The other 105 soldiers had been reassigned to help other towns, and Stone wondered if they could replicate this success elsewhere.

He watched General Voss coordinate a meeting about repairing the school, saw German officials taking notes, saw his own soldiers observing but not interfering, and realized they’d stumbled onto something bigger than one town.

They’d found a way to turn occupation into cooperation.

The question was whether anyone else would be brave enough to try it.

Hey, I’m sorry to interrupt you, but since I know my audience is often a bit older and my videos can be quite long, I might have something interesting for you.

It is called the relax cushion, and it it is specifically designed for long periods of sitting.

So, if you sometimes experience back, hip, or tailbone pain, make sure to check it out via the first link in the description.

Oh, and by the way, then don’t forget to also subscribe.

Now, back to the video.

Word spread through the Canadian First Army like water finding cracks.

In concrete, officers visited Stonestown, walked the streets, asked questions, and returned to their own sectors, wondering if they were doing everything wrong.

By late May and into June of 1945, Canadian commanders in 47 occupied towns began adopting similar models.

They found their own captured officers, their own German administrators, their own ways of creating supervised self-governance.

Some worked better than others, but almost all worked better than the rigid control methods.

By July, the Canadian method, as people started calling it, managed 2.3 million German civilians.

The Canadian sector had the lowest casualties, the fastest reconstruction, and the least resistance.

Not every town succeeded equally.

Some Canadian officers were too strict, micromanaging German administrators and killing the initiative that made the system work.

Others were too trusting, giving authority to men who abused it.

In one town east of Stones, a Canadian lieutenant discovered that the German administrator he’d trusted was a former Gestapo officer who’d hidden his past.

The man had been systematically intimidating civilians who might expose him, creating the appearance of cooperation while consolidating his own power.

When the truth came out, the entire experiment nearly collapsed.

Critics pointed to this failure as proof the Canadian method was dangerous.

But Stone’s response was simple.

Bad men exist in every system.

The question is whether your system catches them.

Ours did.

The German civilians reported him to us because they trusted us to protect them.

That’s how it’s supposed to work.

But most found the balance stone had discovered that sweet spot between oversight and empowerment.

They learned from each other’s mistakes, shared strategies, adapted the model to local conditions.

What started as one captain’s desperate gamble became a network of successful collaborations across the Canadian occupation zone.

The numbers were so dramatic that other Allied forces couldn’t ignore them.

By midJune, Stones Town Square bustled with German workers rebuilding shops while Canadian soldiers supervised church bells ringing for the first time in months.

The scene would have seemed impossible just weeks earlier.

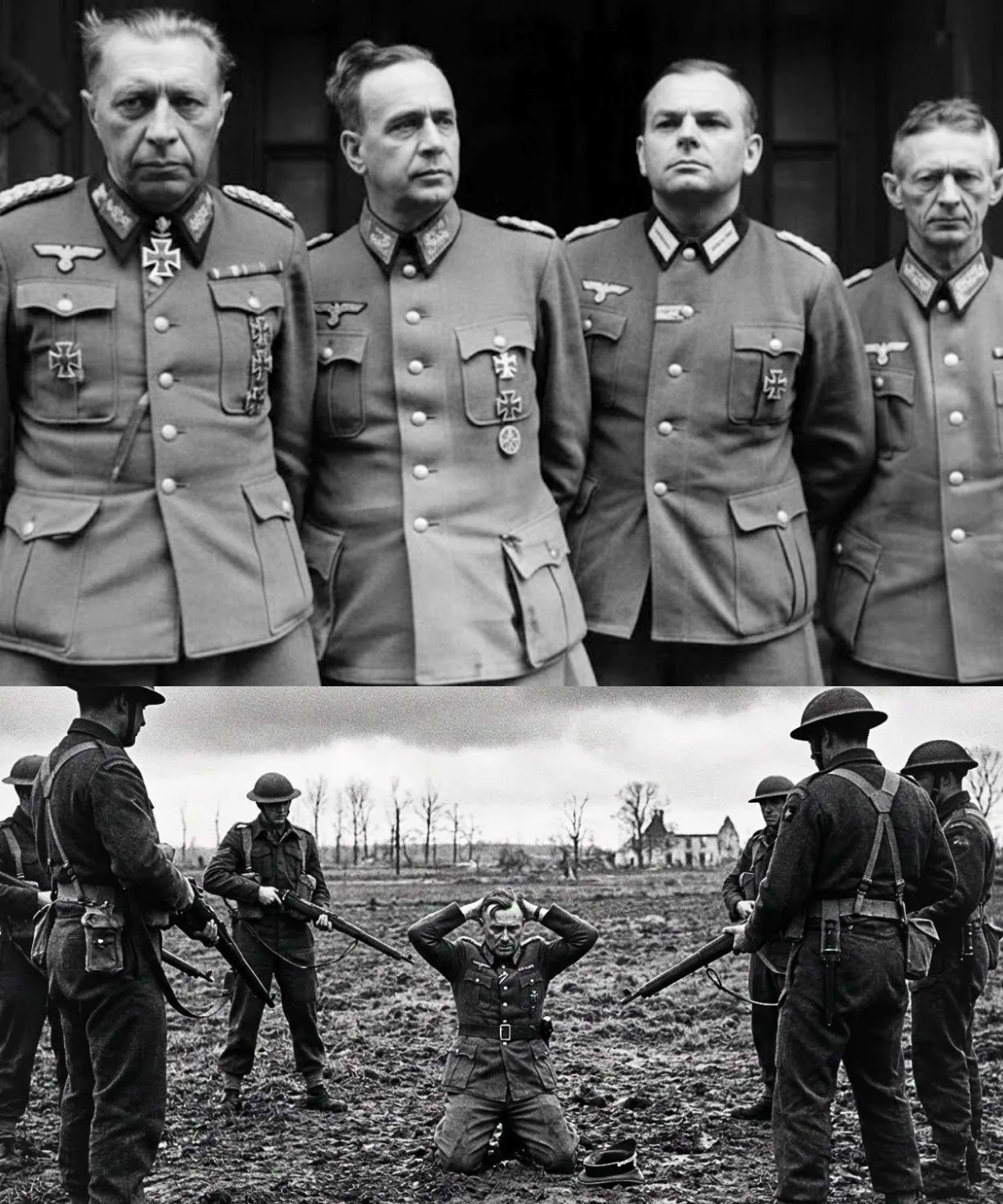

Not everyone celebrated the success.

American military government officials protested loudly.

They argued that Nazis could not be trusted with any authority, that giving power back to Germans, even under supervision, meant letting the enemy regain influence.

They pointed out that many German officials had served under Hitler, that Vermached officers had fought for an evil cause, that kindness now might mean danger later.

Their concerns weren’t entirely wrong.

General Voss had commanded troops in a war of aggression.

The police chief had enforced Nazi laws.

The administrators had run a town under a genocidal regime.

These were uncomfortable truths that Stone thought about late at night when he couldn’t sleep.

Newspapers ran stories questioning whether Canadians were going soft on Germany.

One headline asked if the men who liberated Europe were now coddling the defeated enemy.

Political pressure built on the Canadian government to conform to standard Allied policy to stop experimenting and follow the rules everyone else followed.

Stone received letters from officers he’d never met.

Some praising his innovation, others calling him naive and dangerous.

The debate grew heated because the stakes were enormous.

If the Canadian method worked, it challenged everything the other allies were doing.

If it failed, it might get people killed.

Some critics made valid points.

What about former SS officers hiding among the administrators? What about diehard Nazis waiting for a chance to regroup? The Canadians were betting everything on trust, on the idea that most Germans wanted peace more than ideology.

It was a calculated risk with millions of lives in the balance.

Stone received death threats from anonymous sources.

Someone spray painted traitor on the town hall wall, but the threats came from outside the town, never from within it.

The Germans under his care had too much to lose.

While American and British sectors struggled with direct control, requiring five times more troops, and Soviet zones imposed complete takeovers, the Canadian approach proved dramatically more effective.

Stone found a letter in his files written by a German civilian, translated by one of his men.

It said, “The Canadians treat us as humans, not animals.

This matters more than food.

More than shelter.

When you are treated as human, you act human.

When you are treated as an enemy, you become one.

Stone read it three times, understanding something important about dignity and trust that no military manual had taught him.

The unexpected consequences kept surprising everyone.

German administrators given responsibility for their own people actively worked to suppress the feared werewolf resistance.

Former weremocked officers reported Nazi dieards to Canadian authorities, turning in men they’d served alongside because they wanted peace more than ideology.

Denazification proceeded faster in Canadian zones because Germans policed themselves more effectively than occupiers ever could.

Intelligence officers discovered they learned more from cooperative Germans than they ever extracted through harsh interrogation.

Trust, it turned out, was a better tool than fear.

The scale of implementation grew faster than anyone anticipated.

By August 1945, the Canadian approach expanded across the entire occupation zone.

4.7 million Germans lived under supervised self-administration.

12,000 Canadian troops managed an area that would have required more than 100,000 soldiers using conventional doctrine.

The German civilian government structure included 89 towns and seven cities, all functioning with their own bureaucracies under Canadian oversight.

It was messy and imperfect, but it worked better than the alternatives.

General Voss coordinated it all from Stone’s town, which became an informal training center where other Canadian officers came to learn the method.

Stone watched Voss teaching younger officers how to identify reliable German administrators, how to maintain oversight without micromanaging, how to build trust while staying vigilant.

The general never smiled, never joked, carried himself with the same stiff dignity he’d had when they captured him.

But once Stone overheard him tell a German official, “We lost the war.

Now we must win the peace, even if our conquerors lead the way.

It was the closest thing to Hope Stone had heard from any German.

Within months, the Allied control council formally studied Stone’s approach.

The method that had nearly gotten him court marshaled became the subject of serious analysis by military planners and politicians.

Through 1946, other allied powers quietly incorporated elements of supervised German self-governance into their occupation policies, though pride prevented them from calling it the Canadian method.

The Marshall Plan announced in 1948 adopted the core principle on a massive scale.

Billions of dollars would flow into Europe, but the money would go through German institutions, be managed by German officials, rebuild German infrastructure under German direction.

American planners studied the Canadian occupation reports, noting how supervised self-governance produced faster recovery than direct control.

They saw that Germans who felt ownership of their reconstruction worked harder reported problems honestly and policed corruption themselves.

The Marshall Plans architects never publicly credited Stone’s experiment in that small town.

But the fingerprints of his approach were everywhere in the program’s design.

It was the Canadian method applied to an entire continent and backed by American resources.

The principle was simple.

Give people the tools and trust to rebuild and they will rebuild better than occupiers ever could.

3 years earlier, this idea had been considered dangerously naive.

Now it was official policy of the United States government.

When West Germany wrote its basic law in 1949, creating the structure for their new government, they built in strong protections for local administration.

Towns and cities kept significant power to run their own affairs.

The federal structure preserved the kind of local control that had worked so well under Canadian supervision.

Nobody drew a direct line from Stone’s experiment to the West German Constitution, but the echo was there for anyone who listened carefully.

The postwar German state was built on the principle that empowering local governance worked better than imposing control from above.

That principle had been tested first in a small town in May 1945.

The approach became a template used in other post-war reconstructions.

In Japan, American occupiers learned from the German experience and worked through existing Japanese institutions rather than replacing them entirely.

In South Korea, local administration remained Korean, even under American guidance.

Decades later, when the Soviet Union collapsed and Eastern Europe needed rebuilding, the same principle applied.

Empower rather than impose.

Trust rather than control.

Work with people, not against them.

The lesson from 1945 kept proving useful in crisis after crisis.

Captain James Stone returned to Canada in early 1946 and resumed teaching history at the same rural Ontario high school where he’d worked before the war.

He was 29 years old and felt much older.

He never received a medal for what he’d done in Germany.

His personnel file noted his service was satisfactory.

That was all.

He taught for 32 more years, retiring in 1978.

his groundbreaking work credited simply to Canadian pragmatism.

Years later, a former German official who’d worked under Voss wrote in his memoirs, “The Canadian captain could have treated us as conquered animals.

Instead, he saw us as broken people who needed a chance to rebuild with dignity.

That choice saved more lives than any battle his army won.” Stone never saw those words, but thousands of Germans who lived through those first desperate months knew the truth.

The man who’d almost been court marshaled for trusting them had given them back something the war had taken, their humanity.

In his final years of teaching, Stone kept a single photograph on his desk.

It showed the town square in midJune 1945 with Canadian soldiers and German workers rebuilding together.

students sometimes asked about it.

He’d tell them it represented the moment he learned that the hardest choice and the right choice are often the same thing.

That sometimes following orders means knowing when to break them.

That trust isn’t naive if you’re willing to verify, and that authority means nothing without legitimacy.

The lessons of that German town shaped how he taught history for ye three decades.

Wars end, he’d tell his students.

But how you treat people afterward determines whether peace has a chance.

General Hinrich Voss remained in Stonestown through the summer of 1945, then was transferred to a standard prisoner facility in September.

He went through dennification proceedings like all German officers.

His case was complex.

He’d fought for an evil regime, but had helped prevent chaos after its collapse.

The judges classified him as a follower rather than a leader in the Nazi system.

He received a moderate penalty, time served, and returned to civilian life in 1947.

He became a civil engineer, helping rebuild German infrastructure until his retirement in 1963.

He and Stone never met again.

That lesson, tested in one German town in May 1945, would reshape how the world approached postconlict reconstruction.

In May 1945, Captain James Stone made a choice that nearly got him court marshaled.

He trusted a defeated enemy general to help rebuild rather than simply suppressing the population.

That gamble turned occupation into cooperation and chaos into order.

3 years later, his desperate field experiment became the official policy for rebuilding Europe.

The most effective weapon against postwar collapse wasn’t overwhelming force.

It was the willingness to trust people with their own future.