Bavaria, May 1945.

The village of Graffinir sat silent in the morning light.

Smoke from destroyed buildings drifting through empty streets like ghosts.

Sergeant John Wallace pushed open the door of a stone house, his rifle ready and stopped.

Three children sat on the floor, too weak to stand, their eyes enormous in faces that were mostly skull.

The youngest couldn’t have been more than four.

In the corner, their mother knelt with her hands pressed together, not in surrender, but in prayer.

Wallace lowered his weapon.

He’d seen combat for 11 months, but nothing had prepared him for this.

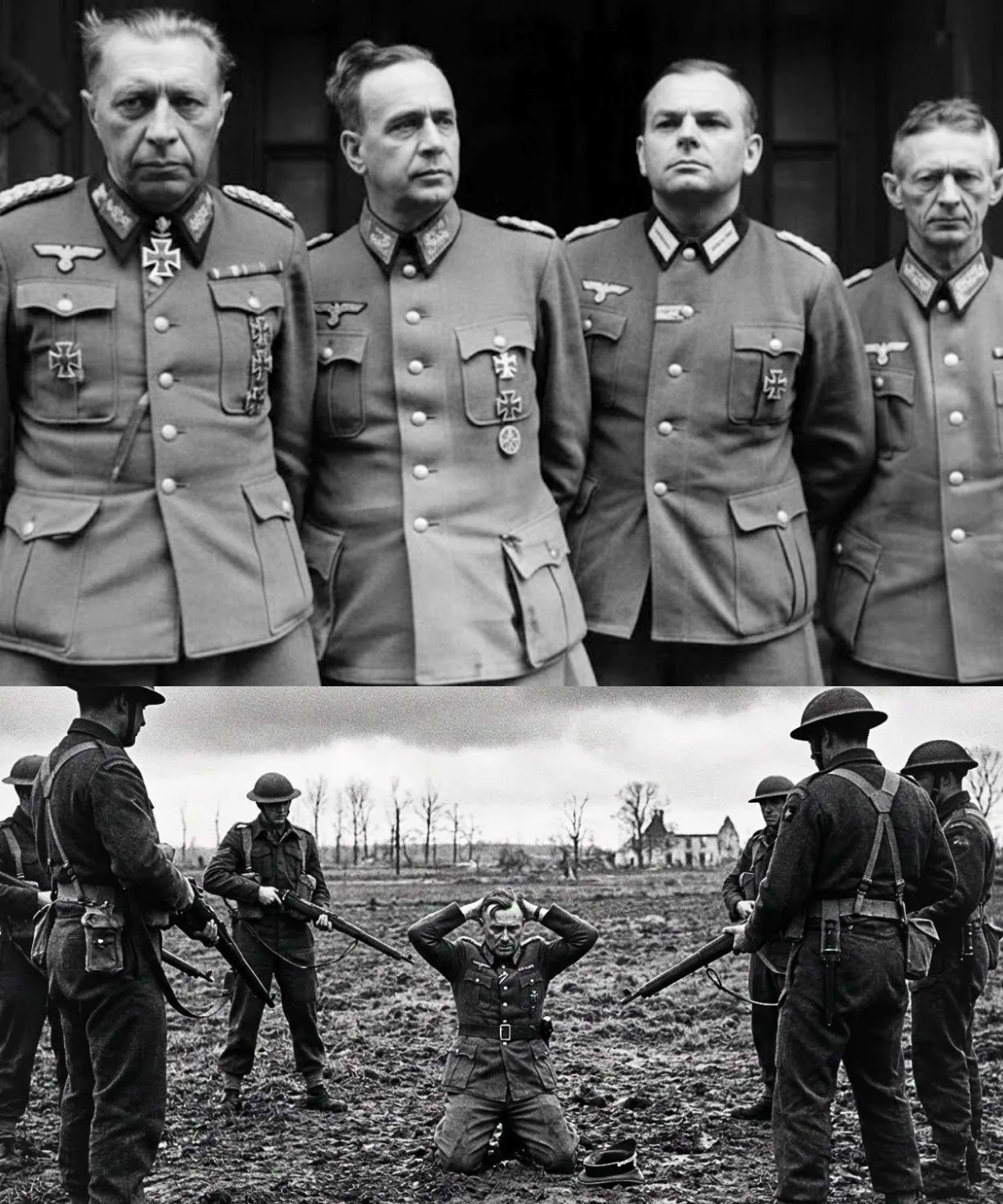

The war in Europe ended on May 8th, 1945, but the suffering didn’t stop with the signatures.

Germany was a landscape of destruction.

Cities reduced to rubble, transportation networks obliterated, agricultural systems collapsed, the civilian population, which had endured years of rationing and bombing, faced a crisis more immediate than occupation, starvation.

Sergeant John Wallace had arrived in Germany with the Third Infantry Division in March 1945, part of the final push into Bavaria.

He was 26, from Iowa, the son of farmers who’d survived the depression by sheer stubbornness and careful resource management.

He understood hunger, had seen it during the dust bowl years, watched neighbors lose everything.

But what he encountered in the weeks after Germany’s surrender was different.

This wasn’t economic hardship.

This was systematic collapse.

The division had taken Graphenwir in late April after brief resistance.

The village was small, maybe 2,000 people before the war and strategically insignificant.

But it sat near a military training ground that had been bombed repeatedly, and the refugees fleeing eastward from advancing Soviet forces had swollen its population to nearly 5,000.

The infrastructure couldn’t handle it.

Food supplies had been cut off.

The black market charged prices only the wealthy could afford.

Everyone else starved.

Wallace’s unit was assigned occupation duties, maintaining order, searching for weapons, processing displaced persons.

Standard procedures for an army that had just defeated an enemy and now had to manage the aftermath.

But within days of arriving, Wallace realized that the most pressing issue wasn’t security.

It was survival.

The first house he searched belonged to the Mueller family.

Hinrich Mueller had been a school teacher before the war.

Called up for service in 1943, captured by Americans in France in 1944.

He was still in a P camp somewhere.

His wife Anna remained in Grafenwir with their three children, Hans age 8, Greta age six, and little Friedrich age four.

When Wallace knocked, Anna opened the door slowly, her face gaunt, her dress hanging loose on a frame that had lost perhaps 40 lb.

Behind her, the children sat on the floor because they lacked the energy to stand.

The house smelled of damp stone and nothing else, no cooking orders, no wood smoke, just cold emptiness.

Wallace had been briefed on non fraternization policies.

Don’t get friendly with the Germans.

Don’t share rations.

Maintain professional distance.

The enemy might be defeated, but they were still the enemy.

But standing in that doorway, looking at children whose ribs stood out like ladder rungs, policy seemed abstract and irrelevant.

When did they eat last? Wallace asked through his interpreter, Private David Klene, who’d grown up speaking German in Milwaukee.

Anna’s hands trembled as she answered.

Klein translated three days ago.

Potato soup.

The last potatoes.

Where’s the father? Prisoner.

American camp.

I don’t know where.

Wallace looked at the children again.

Han stared back with eyes that held no hostility, no fear, just exhausted acceptance.

Greta leaned against her brother, her breathing shallow.

Friedrich had stopped moving entirely, his face pressed against the cold floor.

“Wait here,” Wallace said.

He returned to the temporary command post his unit had established in the village square.

His commanding officer, Captain Robert Morrison, was reviewing requisition forms when Wallace entered.

“Sir, we’ve got a situation.” Morrison looked up.

He was 32, a lawyer from Philadelphia in civilian life.

Practical and by the book.

What kind of situation? Civilian starvation.

I just searched a house three kids who haven’t eaten in days.

And that’s not an isolated case.

From what I’ve seen, half the village is in the same condition.

Morrison set down his pen.

He’d known this was coming.

The intelligence briefings had warned that German civilian populations were facing food shortages, but knowing abstractly and confronting it directly were different things.

What do you want me to do about it, Sergeant? We’ve got rations.

We’re eating three times a day.

These people are dying.

They’re enemy civilians.

They’re children.

The two men stared at each other.

Morrison had spent 11 months enforcing military discipline, following orders, maintaining the chain of command that kept an army functional.

But he’d also spent 11 months watching young men die.

And somewhere in that experience, he developed a pragmatic sense of what mattered and what didn’t.

All right, Morrison said finally medical emergency exception to non fraternization policy.

You can distribute emergency rations to prevent imminent death, but document everything.

If this becomes a scandal, I need paper trails showing we followed humanitarian protocols.

Wallace nodded and left before Morrison could change his mind.

Wallace returned to the Muller house that afternoon with a box of rations canned meat, crackers, chocolate, powdered milk.

Not generous portions, but enough to keep three children alive.

Anna opened the door, saw the box, and her knees buckled.

She caught herself against the doorframe, tears streaming down her face.

[snorts] “Donka,” she whispered.

“Donka, Donka, Dona.” Wallace set the box on the floor.

The children stared at it like it might disappear.

He opened a can of spam, cut it into pieces with his utility knife, handed portions to each child.

They ate slowly, their stomachs too shrunken to handle much food at once.

“Tell her they need to eat small amounts frequently,” Wallace said to Klein.

“Too much at once will make them sick.” Klene translated.

Anna nodded, unable to speak, just holding Friedrich against her chest, while the boy ate his piece of spam in tiny bites.

Word spread quickly.

By evening, a line had formed outside the command postmothers with children.

elderly people who could barely walk, a few men too old or injured for military service, all of them starving, all of them desperate.

Captain Morrison looked at the line and made another decision that violated policy.

He authorized the distribution of rations to anyone who could demonstrate genuine need.

The criteria were simple.

If you looked like you were dying, you got food.

Wallace and his squad, eight men who’d fought from Normandy to Bavaria, became an impromptu relief organization.

They moved through the village house by house, assessing conditions, distributing rations, trying to prevent deaths that would happen if they did nothing.

Private Tommy Martinez from Texas carried a little girl named Lisa four blocks to the medical station because she was too weak to walk.

Her mother walked beside him crying, apologizing in broken English, thanking him over and over.

Martinez, who’d shot German soldiers in combat 3 weeks earlier, felt something crack inside his chest.

Corporal James O’ Conor from Boston found an elderly couple in their 80s who de been locked in their apartment for days.

Unable to descend the stairs for lack of strength, he carried them both down one at a time, settled them in the makeshift aid station, brought them soup he’d made by mixing Krations with hot water.

Private First Class William Chun, Chinese American from San Francisco, discovered a woman trying to nurse an infant despite being so malnourished, she’d stopped producing milk.

Chun brought powdered formula, showed her how to mix it, stayed while the baby drank, making sure mother and child were stable before leaving.

The stories multiplied.

Each house revealed another crisis.

Each intervention prevented another death.

The soldiers worked 14-hour days distributing food, cleaning wounds, carrying people too weak to move, doing the basic work of keeping human beings alive.

Not everyone approved.

Lieutenant Colonel Frank Benson arrived from division headquarters on the third day, walked through Graphanir, observed the relief operations, and called Morrison into a commandeered office.

Captain, what the hell do you think you’re doing? Morrison stood at attention.

Sir, we’re preventing civilian deaths in accordance with Geneva Convention obligations regarding occupied territories.

You’re fraternizing with the enemy.

You’re giving them our rations while American soldiers in the Pacific are still fighting and dying.

These are children, sir, non-combatants, starving non-combatants.

They’re German.

Their fathers and brothers wore uniforms and shot at us.

Their government started this war and fought it until their cities were rubble.

Why should we feed them now? Morrison had anticipated this argument.

He’d prepared a response that was tactical rather than emotional.

Sir, if we let civilians die in areas under our occupation, we create a humanitarian disaster that will undermine our authority and potentially spark resistance movements.

Dead children create martyrs.

Fed children create stability.

Benson studied him coldly.

That’s a very convenient rationalization, Captain.

It’s also the truth, sir.

Benson left without issuing direct orders, which Morrison interpreted as tacid approval.

The relief work continued, though everyone understood they were operating in a gray area where policy hadn’t caught up with reality.

But the real resistance came from within the unit itself.

Sergeant Carl Davis, who’ lost his brother at Omaha Beach, confronted Wallace one evening while they were inventorying remaining rations.

You’re giving food to the people who started this war, Davis said.

His voice was flat, controlled anger barely contained.

I’m giving food to children who didn’t start anything.

Their parents voted for the regime.

Their fathers served in the military.

They supported everything that led to this.

Wallace didn’t have a good counterargument because Davis wasn’t entirely wrong.

Collective guilt was a complicated question, but individual starvation wasn’t complicated at all.

Look, Wallace said, “I can’t fix the past.

Can’t bring your brother back or undo the war, but I can give a can of spam to a 4-year-old who’s dying.

So, that’s what I’m doing.

It’s not justice.

No, it’s mercy.

Sometimes that’s more important.” Davis walked away without responding.

But the next day, Wallace saw him carrying a bag of rations into a house where a family of six was living in two rooms.

Davis didn’t mention it, and Wallace didn’t ask.

Some transformations happened without words.

By the second week, the immediate starvation crisis had stabilized.

People were eating enough to stay alive, but malnutrition had done damage that food alone couldn’t fix.

Children developed vitamin deficiencies that manifested as bleeding gums, night blindness, muscle weakness.

Elderly people’s immune systems had collapsed, leaving them vulnerable to infections that would have been minor under normal circumstances.

The division medical officer, Captain Richard Hayes, established a clinic in the village church, the only building large enough to accommodate the case load.

He worked 18-hour days treating conditions he’d only read about in medical school.

Scurvy, pelagra, severe protein deficiency.

One afternoon, Anna Mueller brought Friedrich back to the clinic.

The boy had been eating regularly for 10 days, but wasn’t improving.

He remained lethargic, his skin developing a yellowish tint, his belly distending despite the food intake.

Hayes examined him carefully.

How long has he been like this? Since winter, Anna said through Klein’s translation.

He got sick in January.

I thought it was just hunger.

Hayes recognized the symptoms.

Protein deficiency so severe it had caused edema and possible liver damage.

The boy needed specialized treatment vitamins, protein supplements, careful monitoring.

Treatment that exceeded what a field medical station could provide.

He needs a hospital, Hayes told Anna.

A real one.

Can I arrange transport to the military hospital in Munich? Anna’s face went white.

They’ll take him from me.

No, you can go with him.

We’ll arrange papers, transportation, everything.

But he needs treatment I can’t provide here.

Anna looked at her son at the American doctor whose kindness made no sense after years of propaganda about enemy cruelty and nodded.

Friedrich and Anna left for Munich the next day in a jeep driven by private Martinez.

Hayes wrote a detailed medical referral, attached it to Anna’s temporary travel documents, included a note explaining the situation.

When the hospital administrators in Munich read it, they admitted Friedrich immediately and assigned Anna a cott beside his bed.

Hayes never learned if Friedrich fully recovered.

The chaos of postwar Germany swallowed individual stories, but he’d done what he could, and that had to be enough.

Not all encounters ended simply.

Two weeks after the initial relief operations began, Wallace was called to a house on the village outskirts, a woman named Elizabeth Hoffman had barricaded herself and her five children inside, refusing to accept American help.

Wallace approached the door cautiously.

Through the window, he could see children sitting on the floor, all of them clearly malnourished, when a girl maybe 6 years old, lying motionless.

Fra Hoffnan Klene called in German.

We’re here to help.

Your children need food in medical care.

No response.

Please let us help.

The door cracked open.

Elizabeth stood there, perhaps 40 years old, her face hollow, her eyes burning with something between rage and desperation.

She spoke rapidly in German, her voice rising to a scream.

Klein translated, “She says we’re the enemy.

We destroyed her home, took her husband, bombed her city.

She says she’d rather die than accept anything from us.

Wallace looked past her at the children.

The youngest was maybe three, the oldest around 12.

All of them watching with the peculiar stillness of people too weak for normal childhood energy.

Tell her I understand her anger, Wallace said.

Tell her she has every right to hate us.

But tell her the children don’t deserve to die for that hatred,” Klein translated.

Elizabeth’s face crumpled.

She sank to her knees in the doorway, hands covering her face, sobs tearing from her throat with a violence that suggested she’d been holding them back for months, maybe years.

Wallace waited.

Sometimes the only thing you could do was wait while someone processed trauma too large for immediate comprehension.

When Elizabeth finally looked up, her eyes were red but clearer.

“Help them,” she whispered in broken English.

“Please help them.” Wallace and Klein entered the house.

They assessed the children four, were severely malnourished, but stable, but the youngest girl, Anna, was in critical condition.

Her breathing was shallow, her pulse weak, her skin cold to the touch.

Wallace radioed for medical evacuation immediately.

While they waited, Klein helped Elizabeth feed the other children small portions of food.

The children ate mechanically without enthusiasm or gratitude, just consuming what was offered with the exhausted acceptance of people who’d given up expecting anything good.

The medical jeep arrived 15 minutes later.

A medic named Tony Ricky scooped up little Anna with practice deficiency, wrapped her in blankets, started in four in the jeep while his driver headed for the clinic at full speed.

Elizabeth started to follow on foot, but Wallace stopped her.

Ride in our jeep.

You need to be with her.

Klein drove Elizabeth to the clinic where Hayes was already preparing for the emergency.

The girl survived barely.

Hayes later told Wallace it had been within an hour of being too late.

Another hour without intervention and she would have died.

Elizabeth stayed at her daughter’s bedside for 3 days.

On the third day she found Wallace at the command post.

She stood in front of him silent for a long moment and spoke in careful English.

I teach before war.

English teacher.

I tell my students Americans are enemy, are cruel, are everything the regime say.

I believe this.

I teach this.

She paused, tears streaming down her face.

I was wrong.

I teach lies.

You save my children.

I I am sorry.

Wallace didn’t know what to say.

Sorry felt inadequate for the machinery of propaganda and hatred and violence that had brought them to this point.

But it was all anyone had inadequate words trying to bridge chasms of experience and ideology.

“Your children are alive,” he said finally.

“That’s what matters.” As weeks passed, the dynamic in Graphan were shifted.

The starving civilians became people with names, histories, personalities.

The American soldiers who’d been trained to see Germans as the enemy found themselves seeing individuals instead.

Private Martinez learned that the little girl he’d carried to the clinic, Lisel, loved to sing despite everything.

Her mother hummed old folk songs while cooking the meager rations they received.

And Lisel would join in with a voice that was surprisingly strong for someone so fragile.

Corporal Okconor discovered that the elderly couple he’d helped, the Bergman’s, had owned a bakery before the war.

Hair Bergman had been a master baker famous locally for his black bread and honey cakes.

He described the recipes to Okconor with passionate detail as if the memory of making bread was itself a form of sustenance.

Private Chun became friends with a teenage boy named Stefan who spoke excellent English learned from British prisoners his father had helped in a work camp.

Stefan had dreams of becoming an engineer, rebuilding Germany’s destroyed infrastructure, creating something better than what the war had left behind.

These connections weren’t official.

They violated the spirit, if not the letter of non-faternization policies, but they happened anyway because human beings are incapable of sustained dehumanization when confronted daily with individual humanity.

Sergeant Wallace found himself spending evenings at the Mueller House, helping Hans with English lessons, teaching Greta simple card games, telling Friedrich stories about Iowa farm life.

Anna would sit nearby mending clothes or preparing food, occasionally interjecting with her own stories about life before the war.

One evening, she asked Wallace why he’d helped them.

He thought about it carefully before answering through Klene.

because you needed help and I could provide it.

Doesn’t seem complicated, but we are the enemy.

You’re a mother trying to keep her children alive.

That’s not the enemy.

That’s just human.

Anna was quiet for a moment.

Then my husband, Hinrich, he is in American camp.

Do you know how they treat prisoners? Wallace did know.

He’d helped process Pose, seen the camps where they were held.

They’re treated according to the Geneva Conventions.

Food, shelter, medical care.

Same as we’re treating you.

He will come home eventually.

Yes.

When repatriation is sorted out on his eyes filled with tears.

For 3 years.

I think he is dead or that if he lives, he suffers.

But you tell me he is fed is safe.

This is dot dot double quotes.

She struggled for words.

This changes everything I believe.

That was the pattern.

Individual acts of mercy accumulating into collective realization that the propaganda had been wrong, that the enemy wasn’t monstrous.

That different didn’t mean less human.

In June, the division received orders to transfer to a new occupation zone.

The soldiers who’d spent 6 weeks in Graphanor would be replaced by a new unit, and the civilians would have to adapt to new faces, new personalities, new relationships.

The night before departure, several German families organized an impromptu gathering in the village square.

They brought what little they could spare Arzad’s coffee, bread made from American flour rations, a few vegetables from gardens that were starting to produce again.

The soldiers contributed cigarettes, chocolate, canned fruit.

It wasn’t a party exactly.

The war was too recent, the losses too raw.

But it was acknowledgment, a formal recognition that something important had happened here, that enemies had become something more complicated than the categories allowed for.

Anna Mueller approached Wallace with a small package wrapped in brown paper.

Inside was a handcarved wooden horse.

Simple but skillfully made.

Hinrich makes these before war, she said in halting English.

For children, I want you to have one for remember.

Wallace took it carefully.

The wood was smooth, aged, the carving showing real craftsmanship.

I’ll remember, he said.

All of you.

This whole time I won’t forget.

Captain Morrison stood with Elizabeth Hoffman, who’ brought all five of her children, including little Anna, recovered enough to walk with help.

The children had drawn pictures for the Americans, who desaved them crude crayon drawings of houses and trees and stick figure soldiers, but precious nonetheless.

“I teach them truth now,” Elizabeth told Morrison through a transl.

I teach them people are good and bad in all nations.

That kindness is choice, not nationality.

That Americans who could have left us to die chose to help instead.

She paused.

I teach them to be better than I was.

Morrison nodded.

He’d spent 11 months in combat, watched friends die, ordered men into situations that destroyed them.

This standing in a village square watching German children give drawings to American soldiers felt like the only victory that mattered.

Not territory captured or enemies defeated, but human connection maintained despite everything that should have made it impossible.

Private Chun talked with Stefan, the teenager who dreamed of engineering.

Keep studying, Chun said.

Germany will need builders, people who can create instead of destroy.

You think Americans will let us rebuild? I think the world needs Germany rebuilt, and it’ll take people like you to do it.” Stefan nodded seriously.

At 16, he was already thinking in terms of decades, long-term planning for a country that barely existed at the moment.

But youth carried hope that older people had lost.

The gathering lasted until midnight.

Then the soldiers returned to their barracks to pack, and the civilians went home to prepare for new occupiers who might not show the same kindness.

Sergeant John Wallace returned to Iowa in October 1945.

He took over his family’s farm, married his high school sweetheart, raised four children, lived what looked from the outside like a completely ordinary life.

But he kept the wooden horse Pana a Mueller had given him on a shelf in his study.

And sometimes he’d hold it while explaining to his children what the war had really been about.

It wasn’t about heroism.

He told them once.

It wasn’t about defeating evil.

Those things mattered, but they weren’t the point.

The point was the choices you made when nobody was watching.

When policy didn’t give clear answers.

The point was deciding that starving children were more important than regulations.

His children didn’t entirely understand.

How could they? They’d grown up with plenty, never knew hunger, couldn’t imagine the moral calculus of deciding who deserved help and who didn’t.

But they absorbed the lesson anyway, that kindness was a choice, that the right action wasn’t always the authorized action, that human beings were more important than systems.

[clears throat] Captain Morrison became a judge in Philadelphia after the war.

He made his reputation for fair sentencing for seeing defendants as individuals rather than case numbers.

When asked about his judicial philosophy, he sometimes mentioned Germany, the village where policy and humanity had come into conflict, and how that experience had taught him that mercy wasn’t weakness, but strength.

Private Martinez opened a restaurant in San Antonio.

On the wall, he hung a photograph of himself in uniform holding a little German girl named Lessle.

When customers asked about it, he told them the story, how he’d carried a starving child to safety, how her mother had cried and thanked him, how that single act had changed his understanding of who the enemy really was.

“I was taught to hate Germans,” he’d say.

The regime gave me plenty of reasons.

But when you’re holding a dying child, nationality doesn’t matter.

Just life and death.

Just whether you’re going to help or walk away.

The German families scattered across postwar Europe and America.

Anna Mueller’s husband, Hinrich, returned from captivity in 1947, found his family alive, and recovering, learned about the American soldiers who’d saved them.

He spent the rest of his life teaching school children about the complexity of morality in wartime.

Using his family’s survival as a case study in how individual choice could transcend systemic hatred.

Elizabeth Hoffman immigrated to America in 1952, bringing her five children to start over in a country that had once been the enemy.

She taught English at a high school in Michigan, and her curriculum always included a unit on propaganda and critical thinking, teaching students to question narratives, to recognize manipulation, to understand that official stories often masked more complicated truths.

I believed lies, she told her students.

I taught lies, and it almost cost my children their lives.

The Americans who saved them weren’t [clears throat] following orders.

They were following conscience.

Learn the difference.

In 1985, 40 years after the war’s end, a reunion was organized in Graffinor.

Veterans from the Third Infantry Division were invited along with German civilians who’d been there during the occupation.

About 50 people came, half American, half German, all of them old now, carrying decades of memory.

John Wallace attended with his wife.

Gana Mueller came with Heinrich, both in their 80s, still sharp despite age.

Private Martinez brought his grown children, wanting them to meet Lisel, who’d become a music teacher in Stogart.

Captain Morrison flew from Philadelphia despite declining health.

Elizabeth Hoffman crossed the Atlantic one more time to see the men who’d saved her daughter, Anna, now a physician working in Berlin.

The village had been rebuilt.

No evidence remained of the destruction, the hunger, the desperate weeks in 1945, but the memories remained vivid for those who had been there.

They gathered in the church where Captain Hayes had run his clinic.

Someone had organized a simple ceremony speeches, translation, sharing of stories.

But the formal program fell apart quickly as people started talking directly to each other, bypassing translators, using broken language and hand gestures to communicate what words couldn’t quite capture.

Anna Mueller found Wallace sitting alone in a pew.

She sat beside him, silent for a moment, then spoke in carefully practiced English.

I want you to know what your kindness meant.

Not just food, not just life, but proof that good exists even in war.

That mercy is possible even between enemies.

My children grew up believing this.

My grandchildren believe this because of you.

Wallace felt tears burn behind his eyes.

I just gave you some rations.

No, you gave dignity.

You saw us as people when everything told you we were enemy.

That is not a small thing.

Hinrich Mueller approached, leaning on a cane, but steady.

He extended his hand to Wallace, who shook it.

“Thank you for my family,” Hinrich said simply.

Wallace nodded, unable to speak.

“What do you say to a man whose wife and children you saved 40 years ago?” “How do you process the weight of that connection across decades?” Martinez stood with Lisel in the church garden.

She’d brought her guitar, played one of the folk songs her mother used to sing.

Her voice was still strong, still beautiful.

Martinez listened with his eyes closed, transported back to that moment when he’d carried a dying child through rubble strewn streets, wondering if he’d be fast enough.

“I became a musician because of you,” Lisel told him when the song ended.

“Music was the first joy I remember after the hunger ended.

I wanted to give that to others.

You’ve given me joy right now, Martinez said.

Thank you.

Elizabeth Hoffman found Captain Morrison on the church steps.

She was frailer than he remembered, but her eyes still held that fierce intelligence.

“You saved my Anna,” she said.

“Now she saves others.

Doctor in Berlin, free clinic for refugees.

She remembers being helpless and decides no one else should feel that way.” Morrison smiled.

That’s a good legacy.

Is your legacy your choice to help when you could walk away.

That choice ripples forward through generations.

The reunion lasted 2 days.

People exchanged addresses, promised to write, took photographs that captured them as they were now old, marked by time, but connected by experiences that transcended normal friendship.

They’d been participants in something rare, a moment when humanity overcame the machinery of war.

On the final evening, someone suggested a toast.

They gathered in the village square with glasses of local beer, standing where 40 years earlier they dshared an awkward gathering, acknowledging transformation that hadn’t had words yet.

Hinrich Mueller spoke first with Anna translating to the Americans who showed mercy when mercy was not required, who saw children instead of enemies, who chose kindness when kindness was difficult.

Wallace responded to the German families who survived against terrible odds, who maintained their humanity despite everything, who taught us that our enemies were just people caught in the same machinery we were.

They drank.

Ben Morrison added to the choices we make in the margins.

When policy doesn’t provide answers and we have to rely on conscience, those are the choices that matter.

More drinking.

Then Elizabeth, her voice shaking to second chances to redemption that comes from admitting you were wrong.

To learning that the enemy of your enemy is not your enemy just another human being trying to survive.

A gathering dissolved into smaller conversations.

As night fell, Wallace found himself standing with Anna and Heinrich, looking up at stars that were probably the same stars they’d seen in 1945, though everything else had changed.

“Do you think it mattered?” Wallace asked.

“This kindness, this help.

In the grand scheme of the war in history, do you think it actually mattered?” Anna didn’t hesitate.

“It mattered to us.

It mattered to every child you saved.

It mattered to every family who learned that Americans were not monsters.

That is enough, is it? Feels small compared to the scale of everything else.

History is made of small moments, Hinrich said through honest translation.

Big events capture attention but small choices feeding hungry child.

Showing mercy to enemy, treating human being with dignity.

Those shape how we remember, how we teach next generation, what kind of world we build.

Wallace considered this.

He despent 40 years occasionally wondering if his actions in graphon were had been meaningful or just temporary bandages on wounds too large to heal.

But standing here with people whose lives he’d literally saved, watching them laugh with other veterans who’d made similar choices, he understood Hinrich was right.

History remembered the grand strategies, the famous battles, the political decisions.

But life was lived in the small moments, the can of spam given to a starving child, the medical care provided to a dying girl, the choice to see a person instead of an enemy.

Those moments accumulated into something larger than any individual act.

A legacy of mercy that rippled forward through generations.

The veterans of Graphonur began dying in the 1990s.

Wallace passed in 1998, Morrison in 2001, Martinez in 2003.

One by one, the generation that had fought the war and chosen mercy in its aftermath faded away.

But the stories remained.

Anna Mueller died in 2006 at age 91.

Her children and grandchildren gathered for the funeral.

And during the ceremony, her eldest son spoke about the wooden horse that had been returned to the family after Wallace’s death.

This horse represents a choice.

He said, “An American soldier could have walked past our house.

Could have followed policy that said, don’t help the enemy.

Instead, he chose to see children who needed help.

That choice saved our lives.

It shaped who our mother became, who we became, who our children are becoming.

One small choice rippling forward through time.

The wooden horse now sits in a museum in Graphenir, part of an exhibit about the post-war occupation.

Visitors read the story.

American soldiers feeding starving German civilians.

policy violated in service of conscience.

Enemies becoming something more complicated than the categories allowed.

Some visitors find it inspiring.

Others find it complicated.

Raise questions about collective guilt and whether Germans deserved help after everything the regime had done.

The debates are valid.

The questions are important.

But they missed the point that Wallace and Anna and all the others understood in 1,945.

Starvation isn’t policy debate.

It’s children dying.

And when confronted with children dying, the only moral choice is to save them.

Everything else, guilt, politics, historical grievance, become secondary to that immediate imperative.

The children saved in Graffenware grew up had families contributed to postwar Germany’s reconstruction.

They became teachers, doctors, engineers, artists.

Their descendants number in the hundreds now scattered across the world.

Most of them never knowing that their existence traces back to American soldiers who violated policy to provide canned meat and chocolate to people who are supposed to be the enemy.

But some know, some carry the story forward, teach their children about the choices that saved their ancestors, maintain connections with families of the American soldiers who made those choices.

They understand that they are living proof of what happens when mercy overcomes hatred.

When individual conscience supersedes institutional policy, when human beings choose to see each other rather than the categories that separate them, the lesson isn’t that war is good or that enemies become friends easily.

The lesson is simpler and more challenging.

That even in war’s worst moments, we can choose mercy.

We can see the human being in front of us rather than the abstraction of enemy.

We can act on cautions even when policy says otherwise.

Those choices are hard.

They risk consequences.

They violate the clean categories that make war manageable.

But they’re the choices that matter, the ones that ripple forward through generations, shaping the world our grandchildren will inherit.

Sergeant John Wallace understood this in May 1945 when he carried food to starving children.

Anna Mueller understood it when she accepted help from someone she’d been taught to hate.

All the others who participated in that brief moment of mercy amid years of violence understood it.

And now we understand it, too, or should.

The wooden horse sits in its museum case.

Mute testimony to a choice made 80 years ago.

The children saved have grown old or died.

The soldiers who saved them are gone.

But the lesson remains simple and urgent.

When confronted with suffering, we can alleviate.

We alleviate it.

Regardless of who suffers, regardless of policy, regardless of the past, we help because we can help.

Because that’s what being human means.

Everything else is justification for turning away.

And turning away when we could save lives is the only truly unforgivable choice.