1904 portrait discovered experts shocked when zooming in on the toy.

The photograph arrived at the Massachusetts Historical Preservation Society on a Wednesday morning in late October delivered in a padded envelope with no return address.

Clare Davidson, the society’s chief conservator, found it on her desk with a brief typed note found in the attic of a house being demolished in Dorchester.

Thought it might be of historical interest.

At 39, Clare had restored countless Victorian era photographs, but this one made her pause the moment she removed it from its protective sleeve.

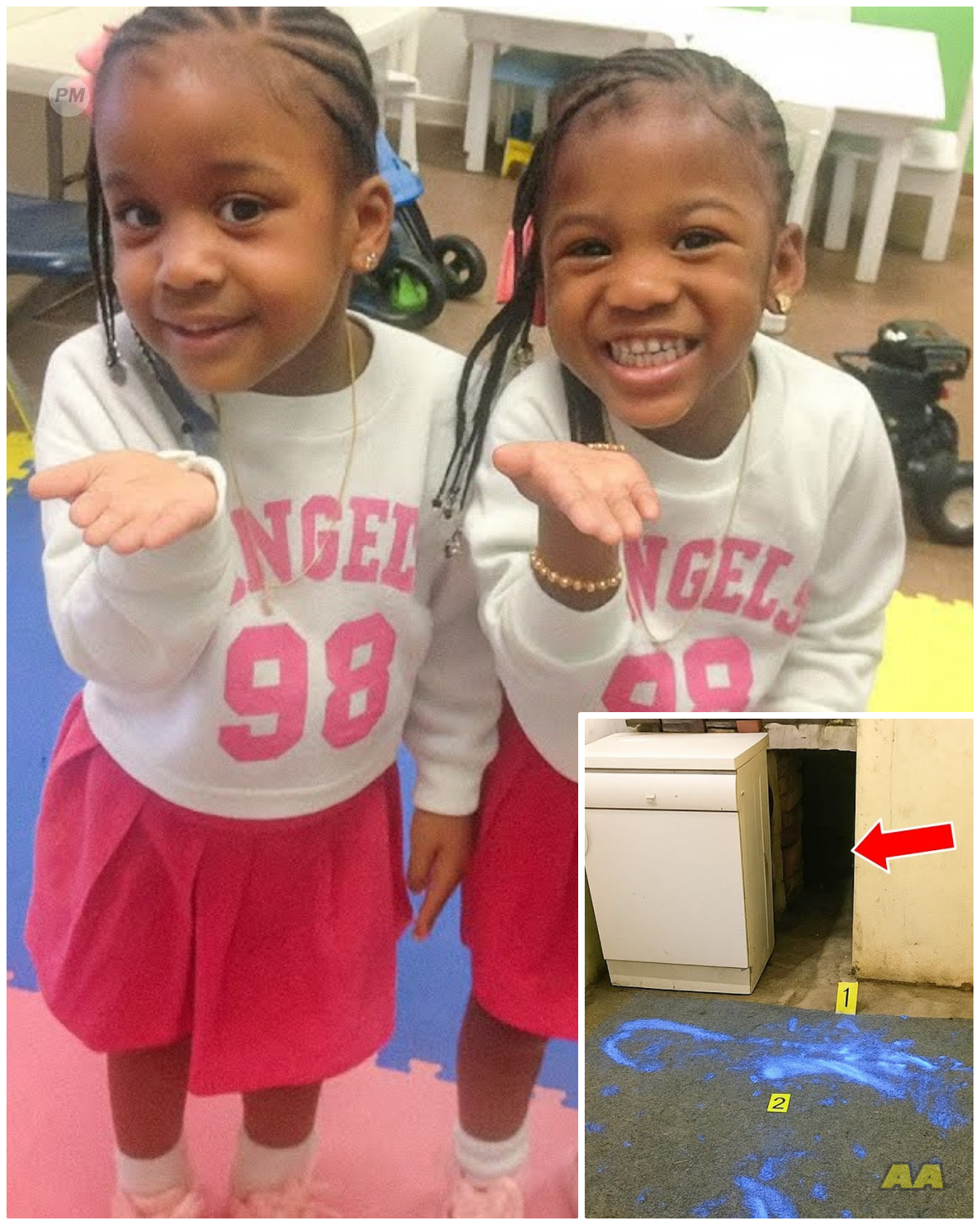

The image showed a boy of perhaps seven or eight years old, seated in an ornate chair that seemed too large for his small frame.

He wore a dark velvet suit with a pristine white collar, his hair carefully combed and parted.

In his lap, he held a tin soldier painted in brilliant reds and blues.

The kind of toy that would have been expensive in 1904.

But something was profoundly wrong with the composition.

The boy sat perfectly still too still for a child of that age who would have struggled to remain motionless during the long exposure times required by early 20th century cameras.

His posture was rigid, almost unnaturally so.

his back straight against the chair, his hands positioned with careful precision around the toy soldier.

Clare adjusted her magnifying lamp, and leaned closer.

The boy’s face was the most disturbing element.

His eyes were open, staring directly at the camera, but there was an absolute absence of expression, no hint of boredom, [music] no suppressed fidgeting, no trace of the awkwardness most children showed when forced to sit for formal portraits.

His skin had a waxy quality that seemed wrong, even accounting for the photographic techniques of the era.

She turned the photograph over.

On the reverse, in faded ink, someone had written, “William, aged 7 years, April 1904, gone to the angels, forever in our hearts.

Clare’s breath caught.” She turned the photograph back over, studying the boy’s face again with new understanding.

The perfect stillness, the waxy complexion, the absolute absence of life in those open eyes.

This wasn’t a portrait of a living child.

This was a post-mortem photograph, a memorial image of a dead boy arranged to appear as if he were merely sleeping or resting.

The practice had been common in the Victorian era and into the early 1900s when childhood mortality was high and photography expensive.

For many families, a post-mortem photograph was the only image they would ever have of a child who died young.

But this photograph felt different somehow, more staged, more deliberate in its composition.

And then there was the toy soldier, pristine, perfectly painted, positioned carefully in the dead child’s hands.

Why that particular toy? Why the elaborate staging? Clare reached for her phone to call Dr.

Marcus Webb, a historian who specialized in Victorian morning practices and post-mortem photography.

Dr.

Marcus Webb arrived at the Preservation Society the following morning.

His academic interest immediately evident in the way he studied the photograph.

At 52, Marcus had spent 25 years researching death culture in America, and his expertise in post-mortem photography was unmatched.

He examined the image with a practiced eye, noting details Clare had missed.

The positioning is very careful, he said, pointing to the boy’s hands.

See how the fingers are arranged around the toy.

That required time and effort.

Postmortm photography was often rushed mortise set in quickly, making positioning difficult, but whoever arranged this child took great care.

The note on the back says his name was William died April 1904 at age 7.

Clare [music] said, “Do you recognize the photographers’s mark?” Marcus turned the photograph over, studying the embossed stamp in the lower corner, Hartley and Suns, Boston.

They were one of several studios that specialized in memorial photography.

They had a reputation for sensitivity and artistry in these difficult situations.

He pulled out a reference book from his leather satchel, flipping to a section on Boston photography studios.

Hartley and Sons operated from 1885 to 1912.

The family business was known for treating grieving families with particular compassion.

They would come to homes rather than requiring families to transport deceased loved ones to the studio, so this was likely taken in the family’s home.

Clare asked almost certainly the chair, the backdrop.

These were portable elements photographers brought with them.

[music] Look at the lighting.

Marcus indicated subtle shadows in the image.

Natural window light supplemented by reflectors, very typical of home sittings.

Clare studied the boy’s clothing again.

The suit is expensive.

The family had some means.

Yes, but notice the toy soldier.

It’s not just any toy.

It’s handpainted with remarkable detail.

These were luxury items in 1904, often imported from Germany or France.

This wasn’t a toy a 7-year-old would have played with roughly.

It’s too pristine.

What are you suggesting? Marcus met her eyes.

I’m suggesting this toy was bought specifically for this photograph.

It was never played with.

It was a prop chosen for a specific reason.

Clare felt a chill run through her.

Why would grieving parents buy an expensive toy for their dead child’s photograph? That, Marcus said quietly, is what we need to find out.

Because in my 25 years studying postmortem photography, I’ve learned that every choice made in these images had meaning.

The clothing, the positioning, the objects included, they all told a story.

We just need to understand what story William’s parents were trying to tell.

He photographed the image from multiple angles, documenting every detail.

I’ll search historical records for families with a child named William, who died in April 1904.

Boston death certificates from that era are well preserved.

We should be able to identify him.

Marcus returned 3 days later with a thin folder of documents.

His expression grave.

He spread papers across Clare’s workbench.

photocopies of death certificates, census records, and newspaper obituaries.

I found him, Marcus said.

William Ashford, born March 1897, died April 15th, 1904.

Address 238 Beacon Street.

He paused, letting Clare absorb the significance of the address.

Beacon [music] Street in 1904 was one of Boston’s most prestigious addresses, home to wealthy merchants and professionals.

Clare examined the death certificate.

The handwriting was elegant but difficult [music] to read.

What does it say for cause of death? That’s where it gets complicated.

The official cause is listed as dtheria.

But look at this.

Marcus pulled out a newspaper clipping from the Boston Herald.

Dated April 18th, 1904.

Tragedy on Beacon Hillong.

William Ashford, son of prominent physician Dr.

Robert Ashford and his wife Margaret, has died at age 7.

The family requests privacy in their time of grief.

Memorial service to be held privately.

[music] It’s unusually brief for a prominent family.

Clare noted.

Exactly.

Wealthy families typically had lengthy obituaries listing the child’s qualities, the family’s grief, details about the funeral.

This is peruncter, almost dismissive.

Marcus pulled out another document.

And there is this a second newspaper notice.

This one from 3 days later in the evening transcript.

The Ashford family wishes to clarify that their son William’s death was due to natural illness and not to any preventable cause.

The family asks that speculation cease and their privacy be respected.

Clare frowned.

That’s an odd thing to publish.

Why would they need to clarify the cause of death? Because people were talking in a community like Beacon Hill.

Rumors spread quickly.

[music] Something about William’s death made people suspicious enough that the family felt compelled to issue a public statement.

Marcus spread out more documents.

The 1900 census showing the Ashford family, Robert, age 35, physician Margaret, age 32, and children William, age three, and Elizabeth, age 1.

The 1910 census showed only Robert, Margaret, and Elizabeth.

Dr.

Robert Ashford was a prominent physician with a practice on Commonwealth Avenue.

Marcus continued, “He specialized in childhood diseases.

Ironically, he published several papers in medical journals about the treatment of scarlet fever and dtheria in children.

Clare looked at the photograph again at Williams carefully positioned body, the expensive toy soldier in his hands.

What really killed him? That’s what we need to find out.

Dtheria is possible it was a common childhood killer in that era.

[music] But the family’s defensive statements, the rushed obituary, the lack of detail suggest there’s more to the story.

Marcus pulled out one final document.

I found this in the society pages from March 1904, 1 month before William died.

It’s a notice about a birthday party.

Master William Ashford celebrated his seventh birthday with a party attended by children from Boston’s finest families.

The boy was described as healthy and spirited.

Healthy and spirited in March, dead in April, Clare said quietly.

Clare contacted the Museum of Childhood in London, sending highresolution images of the toy soldier William held in the photograph.

She received a response two days later from Dr.

Helena Fischer, a curator specializing in antique toys.

Dr.

Fischer’s email was detailed and enlightening.

The soldier in your photograph is a Lucort [music] figure manufactured in Paris circa 1900 to 1904.

These were premium collectible pieces handpainted with exceptional detail.

They were not children’s play things in the traditional sense, but rather display pieces collected by adults.

Each figure costs approximately five franks equivalent to several dollars in 1904 American currency.

A significant sum.

Clare shared the information with Marcus over coffee at a cafe near the Preservation Society.

So, this wasn’t a toy William would have played with.

It was a collector’s item, which raises the question, why is he holding it in his memorial photograph? Marcus stirred his coffee absently.

I’ve been thinking about the symbolism.

In Victorian and Eduwardian memorial photography, every object had meaning.

Flowers represented mourning.

Bibles represented faith.

Personal items represented the deceased interests or achievements.

What would a toy soldier represent? Typically, valor, duty, standing at attention, military virtues.

But for a 7-year-old boy, Marcus shook his head.

It’s an unusual choice.

Most children who died young were photographed with toys.

They actually played with dolls, hobby horses, toy trains, things that represented their childhood.

Clare pulled up the photograph on her laptop.

Look at how his hands are positioned.

They’re not naturally holding the toy.

They’re arranged around it, almost presenting it to the camera.

Marcus leaned closer to the screen.

You’re right.

This isn’t here’s William with his favorite toy.

This is Here’s William with this specific object that means something.

But what? Marcus sat back.

I think we need to talk to Dr.

Fischer about something else.

These Lucort figures, were they ever customized? Could someone commission a specific figure? Clare sent another email to Dr.

Fisher asking about customization options.

The response came within hours.

Yes, Lucart occasionally created custom figures for wealthy clients.

These might depict specific regiments, historical figures, or even portraits of individuals transformed into military figures.

Such commissions were rare and extremely expensive.

Do you have reason to believe the figure in your photograph might be customized? Clare zoomed in on the photograph as far as the resolution allowed, studying the toy soldier’s face.

The paint was too small, the image too old to make out clear features.

But there was something about the proportions, the positioning.

Marcus, she said slowly.

What if this soldier isn’t just any figure? What if it’s meant to represent William himself? Marcus took the laptop, examining the image carefully.

After several minutes, he nodded.

The height proportions of the figure, they’re childlike rather than adult.

Lucot figures typically depicted [music] adult soldiers, but this one has a shorter, younger appearance and the uniform.

He pulled up reference images of Lucot soldiers.

Standard Lucot figures wore historically accurate military uniforms, but this one the uniform is simplified, almost costumelike.

“This could be a custom piece.

Why would parents commission a toy soldier in their son’s image?” Clare asked.

Marcus spent the next week searching newspaper archives and historical society records, looking for any additional information about the Ashford family.

He found it in an unexpected place, the archives of the Boston Latin School, one of the city’s oldest and most prestigious educational institutions.

He called Clare with barely contained excitement.

“I found something.” William had an older brother.

The census records only showed William and his younger sister, Elizabeth, Clare said.

That’s because the older brother Thomas died in 1902.

He was 12 years old.

I found his memorial plaque at Boston Latin School.

But here’s the important part.

I found a letter in the school archives written by Dr.

Robert Ashford to the headmaster after Thomas’s death.

Marcus read from his notes.

Dr.

Ashford wrote, “My son Thomas was a student of exceptional promise whose life was cut tragically short.

In his memory, I am establishing a scholarship for deserving students.

Thomas was fascinated by military history and collected toy soldiers with great passion.

It was his dream to attend West Point.

Though that dream will never be realized, I hope his legacy will inspire other young men to pursue excellence in service to their country.

Clare felt pieces clicking into place.

The toy soldiers were Thomas’s collection.

Yes.

And here’s the crucial detail.

I found Thomas’s death certificate.

Cause of death, accidental drowning, April 1902.

He drowned in the Charles River during an outing with friends.

Two years before William died, Clare said exactly 2 years.

William died in April 1904.

Thomas died in April 1902.

And look at this.

Marcus sent Clare a photograph via email.

This is Thomas’s memorial photograph held in the Boston Latin School archives.

Clare opened the image on her screen.

It showed a boy of about 12 seated formally wearing a school uniform and in his hands he held a toy soldier different from Williams but clearly from the same collection the same manufacturer.

The parents photographed Thomas with one of his beloved toy soldiers.

Clare said it represented his passion, his dream of military service.

Now look at Williams photograph again.

Marcus said the staging, the formality, [music] the toy soldier in his hands at mirrors Thomas’s memorial photograph.

The parents were creating a visual connection between the two boys.

Clare studied both photographs side by side.

The similarities were striking the formal positioning.

The careful arrangement of hands around the toy.

Even the lighting seemed deliberately similar.

Why? Clare asked.

Why create this visual echo? Marcus was quiet for a moment.

I think he said slowly that we need to understand how William actually died.

And I think the answer might involve Thomas’s death 2 years earlier.

He paused.

Claire, I found something else in the newspaper archives.

A brief notice from May 1902, 1 month after Thomas drowned.

It mentions that Dr.

Ashford’s younger son, William, then 5 years old, had been with Thomas when he drowned.

William had witnessed his brother’s death.

Clare and Marcus, met with a child, psychologist who specialized in historical trauma, Dr.

Patricia Lawson, in her office overlooking Boston Common.

They explained what they’d uncovered about the Ashford family.

Two brothers, one who drowned while his younger brother watched.

The second brother dead two years later.

Dr.

Lawson listened carefully, taking notes.

Tell me about the ages.

Thomas was 12 when he drowned.

William was five.

Yes, William would have been seven when he died in 1904.

Marcus confirmed.

The age when children begin to process complex guilt and trauma in more sophisticated ways.

Dr.

Lawson said at 5, William would have witnessed something traumatic, but might not have fully understood the permanence or his potential role.

By 7, he would be old enough to reconstruct the event, to blame himself, to carry what we would now call survivors guilt.

Clare showed Dr.

Lawson the two memorial photographs.

Thomas with his toy soldier.

William posed in an eerily similar manner.

The parents seem to have deliberately created this visual connection between the two boys.

What does that [music] suggest to you? Dr.

Lawson studied the images for several minutes.

In the early 1900s, grief psychology was in its infancy.

Freud was just beginning to publish his theories.

[music] Most people processed grief through religion and social convention.

The death of a child was tragically common, but the death of two children in one family that was devastating.

She pointed to William’s photograph.

The staging of this image tells a story by posing William the same way as Thomas with a toy soldier from Thomas’s collection.

The parents were creating a narrative.

They were saying, “Our boys are together now.” William has joined [music] his brother, but why the military symbolism? Clare asked, “Why toy soldiers for both boys? Soldiers stand at attention, follow orders, do their duty.” There’s a sense of honor and sacrifice in military imagery.

[music] If Thomas’s death was accidental, and especially if William witnessed it, the family might have wanted to reframe both deaths as somehow meaningful or honorable rather than senseless tragedies.

[music] Marcus pulled out his notes.

The official cause of William’s death was dtheria, but the family published those strange defensive statements in the newspapers, insisting his death was from natural illness and not from any preventable cause.

That phrasing is very specific.

Dr.

Lawson’s expression became more serious.

You’re wondering if William’s death wasn’t entirely from disease.

I’m wondering, Marcus said carefully, if a 7-year-old boy carrying two years of guilt about his brother’s drowning might have found his own way to join his brother.

Children that age don’t typically succeed at self harm, but with the right circumstances, dot dot dot.

You’re suggesting suicide, Clare said, her voice barely above a whisper.

I’m suggesting that dtheria is a convenient diagnosis that covers many symptoms.

And I’m suggesting that a prominent physician father would have both the means and the strong motivation to ensure his son’s death was recorded as natural illness rather than something that would bring scandal to the family.

Marcus submitted a formal research request to access historical medical records at Boston City Hospital where Dr.

Robert Ashford had held privileges in 1904.

After weeks of bureaucratic navigation, he received permission to examine non-patient specific documents from the pediatric ward.

He found what he was looking for in the hospital’s administrative records, a notation that Dr.

Ashford had requested a private consultation room in April 1904 for family medical matter.

The entry was dated April 14th, one day before William’s death certificate was filed.

Marcus showed the entry to Clare.

He brought William to the hospital the day before he died, but there’s no admission record, no treatment notes.

Whatever happened in that consultation room wasn’t officially documented.

Clare had been conducting her own research.

Searching through archives of Dr.

Ashford’s published medical papers.

She found an article he’d written in 1903 for the journal of pediatric medicine titled dtheria in young children diagnostic challenges and treatment protocols.

Listen to this.

She said reading from the paper.

The early symptoms of diptherop fever.

weakness, difficulty breathing, can mimic other conditions and may not present with the characteristic throat membrane until advanced stages.

In some cases, by the time definitive diagnosis is made, the disease has progressed beyond effective treatment.

He was an expert on dtheria, Marcus said.

He would have known how to recognize it early, [music] and he would have known how to treat it or how to make another condition look like it, Clare added quietly.

They sat in silence, both understanding the implication.

If William had done something to harm himself, perhaps in a child’s confused attempt to be with his brother, perhaps accidentally in a game gone wrong, Dr.

Ashford would have faced an impossible choice.

Suicide was not only a mortal sin in 1904, but also a cause for scandal that would have destroyed the family’s social standing and his medical reputation.

Marcus found another documentary letter from Dr.

Ashford to the headmaster of a private school dated June 1904, 2 months after William’s death.

I am writing to withdraw Elizabeth’s enrollment for the coming term.

My wife and I have decided to relocate to New York, where I have accepted a position at Presbyterian Hospital.

The memories in Boston have become too difficult to bear.

We hope a fresh start will allow our family to heal.

They left Boston, Clare said, ran from the memories, the questions, the guilt.

Marcus traced the family through census records.

The 1910 census showed them in New York City.

Robert, Margaret, [music] and Elizabeth.

Robert’s occupation was still listed as physician, but his specialty had changed from pediatrics to general practice.

He never published another medical paper.

He couldn’t treat children anymore.

Marcus said he’d lost two sons, and whether William’s death was from illness or something else, Dr.

Ashford would have blamed himself.

Every sick child he saw would have been a reminder.

They found Robert Ashford’s obituary from 1923.

Dr.

Robert Ashford, age 58, died of heart failure at his home in Manhattan.

He is survived by his wife Margaret and daughter Elizabeth.

Dr.

Ashford was known for his early work in pediatric medicine but had spent recent years in general practice.

The family requests that in lie of flowers, donations be made to the American Dtheria Prevention Fund.

Clare located Elizabeth Ashford through genealogical records she had married in 1918, becoming Elizabeth Hartwell and lived until 1967.

Her obituary listed surviving children and grandchildren.

Clare managed to contact one of Elizabeth’s granddaughters, Rebecca Hartwell, who lived in Cambridge.

Rebecca, a woman in her 60s, agreed to meet at a coffee shop in Harvard Square.

She brought with her a small cardboard box containing family photographs and documents.

[music] My grandmother rarely talked about her childhood, Rebecca said, opening the box carefully.

She lost both her brothers when she was young.

I think it haunted her entire life.

She was only three when Thomas drowned and five when William died.

She had almost no memory of them.

Rebecca pulled out a photograph of formal family portrait from around 1901, showing doctor and Mrs.

Ashford with three children.

Thomas stood behind his parents already showing the height of early adolescence.

William, about four years old, sat on his mother’s lap.

Little Elizabeth, barely a toddler, was held by her father.

Grandmother said her mother never recovered from losing the boys.

Margaret Ashford became very fragile, very protective of Elizabeth.

She barely let her out of sight.

Clare and Marcus explained their research, carefully navigating the sensitive question of how William actually died.

Rebecca listened without interruption, her expression growing more troubled.

I need to show you something,” Rebecca said.

Finally, she pulled out an envelope from the bottom of the box.

“I found this among grandmother’s papers after she died.

It’s a letter she wrote, but never sent.

I don’t know who it was meant for.

Maybe a therapist, maybe just herself.

It’s dated 1965, 2 years before she died.” She handed the letter to Clare, who read it aloud quietly.

I was only 5 years old when William died, and for most of my life, I remembered nothing about it.

But as I’ve gotten older, fragments have emerged, not clear memories, but impressions.

Feelings.

I remember William being sad all the time after Thomas drowned.

I remember him crying at night.

[music] I remember him saying he wished he could swim like Thomas.

That he wished he’d been able to save him.

Mother tried to comfort him, but father was distant, consumed by guilt.

I didn’t understand.

And then William got sick.

Or did he? The memories are confused.

I remember father carrying William to his study and locking the door.

I remember mother crying in her bedroom.

I remember hushed voices and the smell of medicine.

And then William was gone.

Father said he’d been sick with dtheria that it had taken him quickly.

But I remember I think I remember father saying to mother late one night, “I had no choice.

He had taken too much.

It was already too late.

I was 5 years old.

I didn’t understand then.

I’m not sure I understand now.

But I’ve always wondered, did William die of disease? Or did he find the medicine cabinet and make a child’s terrible mistake? And did father, rather than call for help, make the decision to let him go, to spare the family the scandal, and William the horror of having his stomach pumped, of being labeled a suicide.

I’ll never know the truth.

But I’ve carried this weight my entire life.

The knowledge that something was wrong with William’s death.

That my parents hid something.

That my family was built on a lie told to protect us from shame.

The coffee shop seemed very quiet when Clare finished reading.

Rebecca wiped tears from her eyes.

Grandmother never sent that letter, never spoke these thoughts aloud, but she kept the letter hidden in her papers, waiting to be found.

Do you believe William’s death was an accident? Marcus asked gently.

I don’t know, Rebecca said, but I believe my grandmother’s memories, and I believe Dr.

Ashford made a choice that night, whatever happened.

However much responsibility he bore, he decided the family’s reputation mattered more than the truth.

Marcus and Clare met one final time at the preservation society, sitting before the photograph of William that had started their investigation.

They now knew or believed they knew the truth behind the image.

William Ashford, 7 years old, dead from either dtheria or from an accidental overdose of medicine his father may have allowed to become fatal rather than risk the scandal of treatment.

Photographed in death, holding a toy soldier from his dead brother’s collection, posed to mirror his brother’s memorial portrait, staged to suggest he had honorably joined Thomas rather than died from guilt, grief, and possibly his own confused actions.

The toy soldier was a symbol.

Clare said a visual language saying both boys were brave.

Both stood at attention.

Both served their duty even in death.

And it protected the family narrative.

Marcus added, “No one looking at these memorial photographs would question the deaths.” “Two tragic losses, yes, but framed as honorable, almost noble.” The military symbolism elevated their deaths above mere accident or god forbid in muing noatroclair looked at William’s face again that perfect stillness the eyes open but empty the small hands arranged around the painted soldier he was 7 years old he’d watched his brother drown 2 years earlier he carried that trauma until it destroyed him whether through making him vulnerable to illness or through his own actions and then his parents staged this photograph to hide the truth not just hide it.

Marcus corrected gently to rewrite it.

To give William’s death a meaning and dignity that the actual circumstances might not have allowed.

In their grief and shame, they created a fiction that would comfort them and protect their surviving daughter from scandal.

[music] Marcus pulled out copies of both memorial photographs.

Thomas and William, brothers separated by two years in death, united in these carefully staged images.

You know what’s most tragic? These photographs worked for over a century.

No one questioned them.

They were simply memorial images of two boys who died young.

The truth was successfully buried until we found the defensive newspaper notices.

[music] Until we traced the family history, until Elizabeth’s letter surfaced, Clare [music] said, “Even then, we can’t be absolutely certain what happened.

We have circumstantial evidence, suggestive patterns, a granddaughter’s fragmentaryary memories, but we’ll never have definitive proof.

Maybe that’s appropriate, Marcus said.

Maybe some truths are meant to remain partially hidden, known but not proven, understood but not spoken aloud.

Clare prepared the photograph for proper archival storage along with a detailed documentation of their research.

She wrote a careful summary of their findings, noting the historical context of postmortem photography, the significance of the toy soldier, the family’s tragic history, and the questions that remained unanswered.

What will the archive label say? Marcus asked.

[music] Clare thought for a moment.

William Ashford 1897 to 1904.

Memorial photograph.

The staging of this image reflects complex family grief following the loss of two sons and the evolving practices of commemorative photography in early 20th century America.

Diplomatically vague, Marcus noted with a slight smile.

Appropriately respectful, Clare countered, “These were real people who suffered real tragedies.

Whatever choices Doctor and Mrs.

Ashford made, they were made in grief, trying to protect their surviving child and preserve what remained of their family.

Three months later, Clare organized a small exhibition at the Massachusetts Historical Society titled Silent Witnesses: The Truth Behind Memorial Photography.

The exhibition explored post-mortem photography as both art form and social practice, examining how families used these images to process grief, memorialize loved ones, and sometimes rewrite painful histories.

William Ashford’s photograph was displayed alongside Thomas’ with explanatory text describing the boy’s deaths and the symbolic connection their parents created between the memorial images.

The text was carefully worded, noting the family’s losses without speculating definitively about the exact circumstances of William’s death.

Rebecca Hartwell attended the opening, bringing her adult children.

They stood together before their ancestors photograph.

Three generations looking at a boy who had died more than a century ago.

Rebecca read the explanatory text aloud to her children, then added quietly, “My grandmother carried the weight of what might have happened for her entire life.

Maybe this exhibition will finally let her rest.

The exhibition attracted attention from scholars studying Victorian death culture, childhood mortality, and the history of grief.

Several visitors shared their own family stories of postmortem photographs, memorial practices, and the ways families in earlier eras had processed loss with limited psychological understanding or social support.

One visitor, an elderly man, stood before William’s photograph for nearly an hour.

Finally, he approached Clare.

My great uncle died in 1906 at age 6.

He said, “My family has a similar photograph.

He’s dressed in his Sunday best holding a book.

For my entire life, we believed he was alive in that photograph, just sitting very still.

But looking at your exhibition, I realize he was already gone.” It explains why we never talked about him.

Why the photograph was kept hidden in a drawer rather than displayed.

The shame wasn’t about his death.

It was about how we chose to remember him, creating a fiction rather than accepting the truth.

Clare watched visitors move through the exhibition, seeing recognition on their faces as they connected historical practices to their own family stories.

The boundary between the living and dead had been much more porous in earlier era.

Families kept bodies in their homes, photographed deceased loved ones, created elaborate morning rituals.

Modern sensibilities found these practices morbid.

But for people living with high childhood mortality and limited medical intervention, they were necessary tools for processing grief.

Marcus joined Clare near the end of the exhibition’s first day.

You’ve done something important here, he said.

You’ve restored context and dignity to these images.

People can look at William’s photograph now and understand the full story.

The tragedy, [music] yes, but also the love that led his parents to create this memorial.

However problematic their choices might seem from our modern perspective, Clare looked at William’s photograph one last time before the exhibition closed for the evening.

The toy soldier in his hands, the careful positioning meant to echo his brother’s portrait.

The elaborate staging designed to transform tragedy into something more bearable of it, spoke to the universal human need to find meaning in loss, to create narratives that help us survive grief.

The truth is, Macabra, Clare said softly.

A child dead, possibly by his own hand, either accidentally or intentionally in the aftermath of witnessing his brother’s drowning.

Parents who may have prioritized reputation over transparency.

A family fractured by loss and shame.

But the truth is also deeply human, Marcus added.

People doing their best to survive unimaginable pain, making choices we might not agree with, but can perhaps understand.

The photograph is Macabra.

Yes, but it’s also evidence of how love persists even in the darkest circumstances.

How families try to protect each other.

How we create stories that allow us to keep living after the unbearable happens.

The exhibition ran for 6 weeks.

William Ashford’s photograph, which had arrived anonymously in a padded envelope, was now properly contextualized and preserved.

Its story told as completely as historical evidence allowed.

The truth behind the image was more tragic and complex than anyone had imagined when they first looked at a boy holding a toy soldier.

But perhaps that’s always true with photographs.

They show us surfaces while hiding depths, preserving moments while concealing contexts, offering evidence while protecting secrets.

Williams photograph had kept its secrets for 120 years now.

Finally, someone had listened to what it was trying to say.

Not just about a boy’s death, but about a family’s grief, a father’s impossible choices, and the lengths people will go to protect those they love, even after death.

The toy soldier remained forever in Williams hands.

A symbol whose meaning had transformed over a century from military valor to fraternal connection to evidence of family tragedy.

Two, finally, a reminder that historical truth is always more complicated, more human, and more heartbreaking than the stories we tell ourselves.