1890 motherdaughter photo unearthed and experts are startled by what they find.

The storage room of the Boston Historical Society smelled of old paper and dust.

Sarah Mitchell, a curator specializing in 19th century photography, carefully lifted the lid of a wooden crate that had been sealed since 1953.

Inside, wrapped in yellowed tissue paper, lay dozens of glass plate negatives and cabinet cards from defunct photography studios across Massachusetts.

She had spent three weeks cataloging donations, most unremarkable, family portraits, wedding photographs, stiff-faced children in their Sunday best.

But when she unwrapped the 23rd photograph, her hands paused.

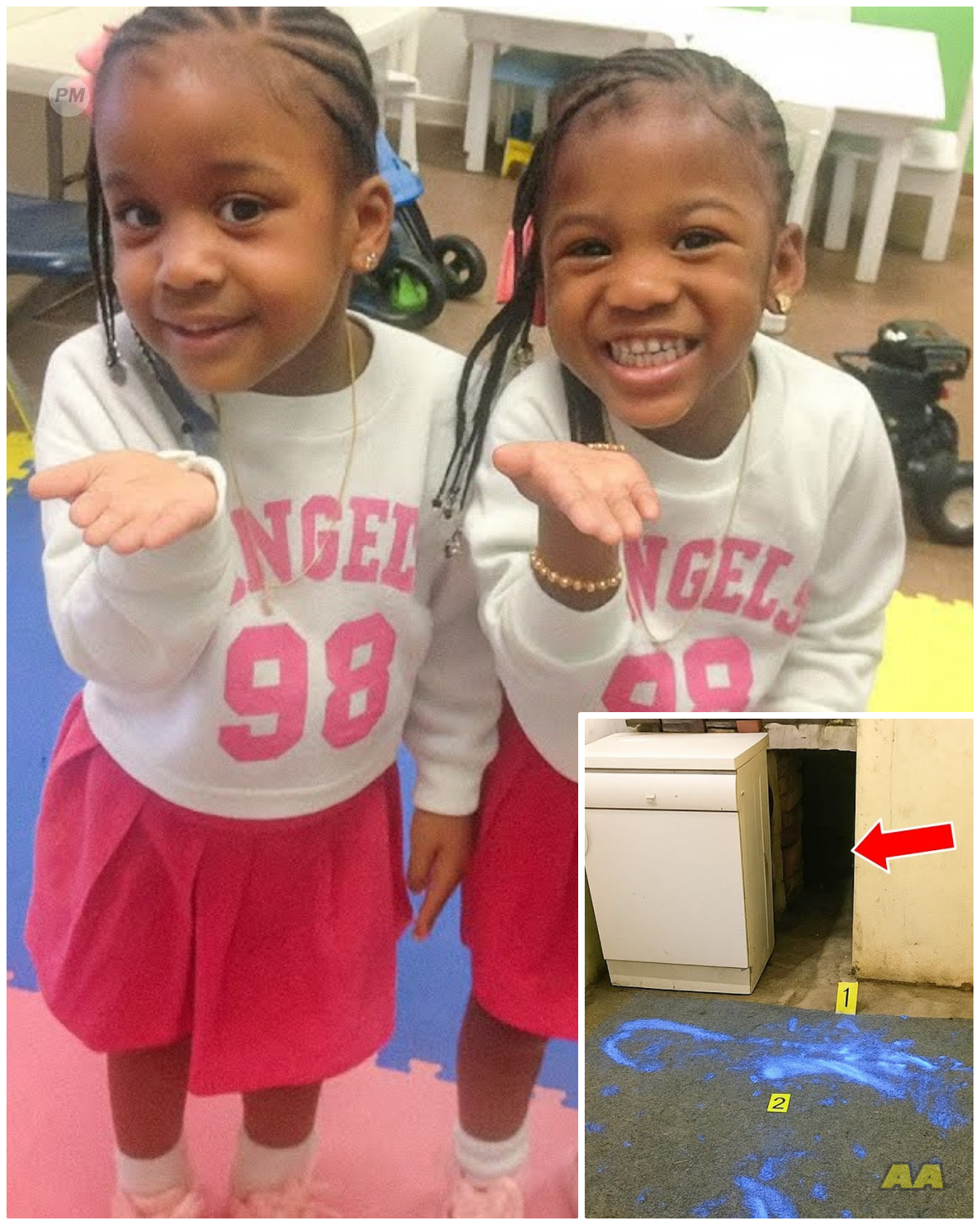

The image showed two women in an ornate studio setting surrounded by painted backdrops of Roman columns and velvet drapes.

Both wore identical black morning dresses with high collars and long sleeves.

The older woman, appearing to be in her mid-30s, sat rigidly in an upholstered chair, her face composed but strained.

Behind her stood a younger woman, perhaps 17 or 18, one hand resting on the seated woman’s shoulder in a gesture that seemed protective rather than affectionate.

Sarah squinted at the faded inscription on the back.

Mrs.

Katherine O’Brien and daughter Rose, Lel, Massachusetts, April 1890.

Something about the photograph felt wrong.

Not the composition or the technical quality.

Those were standard for the era.

It was something in their faces, in the tension visible even through the formal poses required by 1890s portrait photography.

She carried the photograph to her desk and positioned it under the magnifying lamp.

The enhanced lighting revealed details invisible to the naked eye, the texture of the fabric, the shadows that fell across their faces, the way their hands were positioned.

Sarah’s breath caught.

The mother’s left sleeve had ridden up slightly, exposing her wrist.

Even through the sepia tones and age of the photograph, she could see dark marks on the skin, bruises partially healed, forming a ring around the wrist as if someone had gripped it violently.

She reached for her digital scanner, her pulse quickening.

In 15 years of archival work, she had learned to recognize the signs of hidden stories in old photographs, the forced smiles that didn’t reach the eyes.

The strategic positioning of hands to hide injuries, the formal portraits taken not for memory, but for documentation.

As the highresolution scan loaded on her computer screen, Sarah zoomed into the daughter’s hands, clutched against her dark skirt, held deliberately in frame, was a folded document.

The edges were crisp, official, legal paperwork.

Sarah leaned closer to the monitor, her training telling her this was more than a simple family portrait.

The identical morning dresses suggested a recent death.

The bruises suggested violence.

The document suggested legal proceedings.

“What happened to you?” she whispered to the two women frozen in time.

Their eyes staring back at her across 134 years with an expression she now recognized as fear carefully disguised as dignity.

Sarah spent the next morning enhancing the digital scan with specialized software used by forensic archivists.

She adjusted contrast levels, sharpened edges, and isolated specific areas of the image, working methodically through each section of the photograph.

The marks on Katherine O’Brien’s wrists became clearer with each adjustment.

They weren’t accidental bruises from factory work.

Sarah had examined hundreds of photographs of mill workers and knew the difference.

These were deliberate, personal injuries, finger-shaped contusions that wrapped around both wrists, suggesting someone had grabbed her with considerable force.

But it was the daughter’s face that disturbed Sarah most.

Rose’s expression, carefully neutral for the camera, showed micro details that the original photographer would never have seen, the tension around her eyes, the slight downturn of her mouth that suggested not sadness, but suppressed anger, the rigid set of her jaw.

Sarah pulled up reference materials about portrait photography in 1890s Massachusetts.

Studio sessions were expensive, often costing a week’s wages for workingclass families.

People didn’t commission formal photographs casually.

They marked significant life events, marriages, anniversaries, commemorations of the dead.

The morning dresses indicated someone had died recently.

But who? And why would a grieving widow and her daughter need to pose with legal documents visible in the frame? She called Dr.

James Patterson, a professor of American social history at Boston University, who specialized in industrial era New England.

“James, I need your expertise on something unusual,” she said when he answered.

“How unusual? Potentially criminal.” 45 minutes later, Patterson stood beside her desk, studying the enhanced images on her computer screen.

He was a meticulous scholar, known for connecting historical dots others missed.

“Bues,” he said immediately, pointing to Catherine’s wrists.

“Defens of injuries, most likely.” “Someone grabbed her hard enough to leave marks that were still visible weeks later when this photograph was taken.” “That’s what I thought,” Sarah confirmed.

Patterson zoomed in on Rose’s hands.

“And she’s holding what appears to be a legal document.

See the header? That’s official Massachusetts state formatting.

Court documents use that style.

Why would they photograph court documents evidence? Patterson said quietly.

In 1890, photographs were increasingly used in legal proceedings.

Character evidence, documentation of injuries, proof of identity or relationship.

He looked at Sarah directly.

This wasn’t a memorial portrait.

This was legal documentation.

Sarah pulled up her preliminary research.

The photograph came from the Mercer studio in Lel.

I found the business ledger.

It lists this session as April 12th, 1890.

Payment of $150, which was substantial money.

Two days wages for a mill worker, Patterson noted.

Someone thought this photograph was critically important.

They studied the image together in silence.

Two women in identical morning clothes, one showing signs of physical abuse, one clutching legal papers, both maintaining rigid composure for a camera that would preserve their images for posterity.

We need to find out who died, Sarah said.

and why these two needed photographic evidence.

Two months later, Patterson nodded slowly.

I’ll check death certificates and probate records for Lel in early 1890.

Sarah and Patterson met at the Massachusetts State Archives in Boston the following morning.

The reading room was quiet, filled with researchers hunched over documents and microfilm machines.

They had requested death certificates and probate records from Lel for January through March 1890.

The death certificates arrived first.

Thick folders of handwritten forms documenting every recorded death in the city during those three months.

Lel had been a dangerous place in 1890.

Industrial accidents, tuberculosis, chalera, childhood diseases.

The mortality rate among working-class families was staggering.

Patterson worked through February while Sarah examined January.

The names blurred together.

Infants who live days, workers killed by machinery, elderly immigrants succumbing to harsh winters and poorly heated tenementss.

Here, Patterson said suddenly.

Patrick O’Brien, age 32, February 18th, 1890.

Cause of death.

Traumatic head injury sustained in fall at Pacific Mills.

Sarah moved to read over his shoulder.

The certificate was detailed as industrial accident deaths required investigation.

Patrick O’Brien had been a loom fixer at the Pacific Mills, one of Lel’s largest textile factories.

According to the report, he had fallen from a second story catwalk onto the factory floor, [music] striking his head on an iron gear assembly.

death had been instantaneous.

The informant listed on the certificate was Katherine O’Brien, wife.

So, Katherine was widowed in February, Sarah said, and the photograph was taken in April, two months later.

Patterson pointed to another line on the certificate.

Look at the investigating officer’s notes.

Witness statements indicate deceased had been drinking.

History of inmperate behavior reported by supervisors.

Drinking on the job or arriving to work intoxicated, Patterson said.

Either way, it suggests Patrick had problems with alcohol.

He flipped through his reference notes.

In 1890s, mill culture that usually meant domestic problems as well.

Irish immigrant workers faced terrible discrimination, crushing poverty, dangerous working conditions.

Alcoholism was epidemic, and domestic violence often accompanied it.

Sarah thought of the bruises on Catherine’s wrists.

You think Patrick was abusive? I think it’s likely, Patterson said carefully.

And I think his death, whether accidental or not, may have triggered legal questions that required Catherine to defend herself.

They requested probate records next.

If Patrick’s death had involved any legal complications, there would be documentation.

The probate file for Patrick O’Brien was surprisingly thick.

Sarah opened it carefully, and the first document made her pulse quicken.

Investigation into the death of Patrick Michael O’Brien conducted by the Lowel Police Department and the Middle Sex County District Attorney’s Office, March 1890.

Patterson leaned in.

They investigated his death as potentially criminal.

Sarah read aloud, “Based on witness testimony indicating prior altercations between the deceased and his wife, and given the suspicious circumstances of the deceased’s presence on an elevated catwalk during non-working hours, this office has deemed it necessary to investigate whether the death was accidental or resulted from foul play.

They suspected Catherine of murder.” Patterson breathed.

The probate file contained witness statements from factory workers, neighbors, and supervisors.

The picture they painted was grim.

Patrick O’Brien is a violent drunk who regularly beat his wife, who had threatened her life on multiple occasions, who had been seen arguing with Catherine just hours before his death.

Several witnesses reported hearing Catherine tell neighbors she couldn’t take it anymore.

One supervisor stated that Patrick had shown up to the factory intoxicated on the day of his death, and that Catherine had appeared at the mill that afternoon looking for her husband with a desperate expression.

She was at the factory the day he died,” Sarah said quietly.

Patterson found another document, a statement from Catherine herself, given to police on March 3rd, 1890.

Her words were transcribed in formal legal language, but the emotion came through clearly.

Sarah read it aloud.

My husband was not a kind man.

He hurt me many times.

That day, he had been drinking since morning.

I went to the mill because I feared he would lose his position and we would have no money for food.

I found him on the floor.

He was already dead.

I did not push him.

I would not, but I will not pretend to grieve a man who gave me only pain.” The room seemed colder suddenly.

Sarah imagined Catherine, 34 years old, facing police interrogation, admitting she didn’t mourn her abusive husband, while knowing that honesty might lead to a murder charge.

“There’s more,” Patterson said, pulling out additional documents.

“The case was closed April 8th, 1890.

Ruled accidental death.

Catherine was cleared of all suspicion 4 days before the photograph was taken.

But Sarah found something else in the file.

Another legal petition.

This one dated March 15th, 1890.

Filed by someone named Michael Donnelly, identified as Patrick O’Brien’s brother-in-law.

Petition for emergency custody of minor child.

Sarah read.

Michael Donnelly requests that Rose O’Brien, age 17, daughter of the deceased Patrick O’Brien and Katherine O’Brien, be removed from her mother’s care and placed in the custody of the petitioner on grounds that Katherine O’Brien is of unsuitable moral character and temperament to raise a child.

Patterson’s face darkened.

He was using the murder investigation against her.

Even though she hadn’t been charged, he was arguing that mere suspicion made her unfit.

Sarah scanned the legal arguments.

Donnelly claimed that Catherine’s admission of absence of grief and her history of discord with the deceased demonstrated moral deficiency.

He argued that Rose would be better served in his household where she could be properly guided and protected from her mother’s influence.

This is about control, Sarah said, and probably about money.

If Rose was removed from Catherine’s custody, who would inherit whatever little Patrick left behind? They found Catherine’s response filed March 22nd, 1890.

The petitioner ignores the truth of my late husband’s character.

He was a violent man who brought suffering to his family.

My daughter Rose is 17 years old, nearly an adult, and wishes to remain with me.

We have survived years of hardship together.

The petitioner seeks to punish me for surviving my husband’s cruelty.

Attached was a note from the presiding judge dated April 2nd.

Given the serious nature of the allegations, this court requires additional evidence of Katherine O’Brien’s fitness as a parent.

Hearing scheduled April 18th, 1890.

Sarah and Patterson looked at each other with sudden understanding.

The photograph, Sarah said, they needed it for the custody hearing.

Sarah requested the complete court transcript from the April 18th hearing.

[music] When it arrived 3 days later, she and Patterson read through it together, and the voices of Catherine and Rose O’Brien emerged from the formal legal language like ghosts speaking across time.

Rose had testified first.

The court clerk had noted her demeanor.

The witness appeared composed and spoke clearly, though with evident emotion.

The prosecutor, questioning her on behalf of Michael Donnelly, had been aggressive.

The transcript recorded the exchange.

Miss O’Brien, is it true your mother expressed no grief at your father’s death? My mother expressed relief, sir.

There’s a difference.

Relief at a husband’s death seems callous.

Not when the husband spent years making his family’s life a misery.

The judge had intervened, but Rose had continued.

My father drank.

He was violent.

He hurt my mother regularly.

I witnessed it my entire life.

When he died, I felt the same relief my mother did.

Does that make me callous as well? Sarah paused, reading, impressed by the 17-year-old’s courage.

In 1890, for a working-class Irish immigrant girl to speak so directly to male legal authorities would have required extraordinary bravery.

The prosecutor had tried another approach.

Your uncle Michael Donnelly can provide you with a stable home, proper guidance.

My uncle wants control of whatever little money my father left, and he wants to punish my mother for surviving.

I’m 17 years old, sir.

In one year, I will be legally an adult.

I choose to remain with my mother who has protected me all my life.

Not with a man I barely know who supported his brother’s cruelty through years of silence.

Patterson whistled low.

She destroyed him.

Catherine’s testimony had been equally powerful.

When asked about the bruises still visible on her wrists, the same bruises captured in the photograph.

She had answered with devastating calm, “My husband grabbed me that way many times.

These particular marks came from three days before his death when he had been drinking and became angry that I had hidden money for food instead of giving it to him for the tavern.

He grabbed my wrists and twisted until I thought the bones would break.

I have had worse.

The prosecutor had tried to suggest she had followed Patrick to the mill with intent to harm him.

Catherine’s response was recorded verbatim.

I went to the mill because I was afraid he would lose his job and we would starve.

I found him already dead on the factory floor.

I did not push him.

I did not touch him.

But I will not stand before this court and pretend I wished him alive.

He made every day of my life frightening and painful.

I am sorry for the manner of his death.

No one deserves to die that way, but I am not sorry to be free of him.” The judge had asked one final question.

“Mrs.

O’Brien, if this court allows your daughter to remain in your custody, what kind of life can you provide for her?” Catherine’s answer had been simple but profound.

A life without fear, your honor.

A life where she can work, save money, perhaps marry someone kind.

a life where no man will hurt her as her father hurt me.

That is all I can promise, but it is more than she had before.

The court transcript included a detailed description of evidence presented during the hearing.

Among the documents submitted by Catherine’s attorney was the photograph from the Mercer studio taken just 6 days before the hearing.

The attorney’s argument was recorded in the transcript.

Your honor, I present photographic evidence of Mrs.

Katherine O’Brien and her daughter Rose taken April 12th of this year at the Mercer Studio in Lel.

This photograph demonstrates the respectability, dignity, and mutual devotion of mother and daughter.

You will observe their proper morning attire, their composed demeanor, and the evident bond between them.

Sarah pulled up the enhanced digital scan on her laptop.

Now she understood every element of the photograph’s composition.

The identical morning dresses weren’t just about showing respect for the dead.

They were about presenting a united front, demonstrating that Catherine could properly guide her daughter in social conventions.

The formal studio setting, with its painted columns and velvet drapes, conveyed dignity and respectability, countering accusations of moral unfitness.

Rose’s protective hand on her mother’s shoulder, showed familial unity and mutual support.

When the document clutched in Rose’s hands, Sarah now understood it was likely the custody petition itself, held deliberately in frame as a visual assertion of their determination to stay together.

The judge’s ruling had been surprisingly sympathetic, as recorded in the transcript.

This court has examined character testimony from numerous witnesses, all of whom attest to Katherine O’Brien’s good character and her dedication to her daughter’s welfare.

The photograph submitted as evidence shows a mother and daughter of respectable appearance and evident mutual devotion.

Rose O’Brien, having reached the age of 17, has testified clearly and convincingly of her wish to remain with her mother.

This court finds no grounds to remove the child from her mother’s care.

The petition is denied.

Patterson found a final note from Catherine’s attorney dated April 20th, 1890.

Custody matter resolved in client’s favor.

Fees paid in full.

Photograph returned to client per request.

She kept the photograph, Sarah said.

Even after the hearing, even after she won, she kept it.

This wasn’t just legal evidence.

It was proof that she had fought for her daughter and won.

They sat in silence, contemplating what they had uncovered.

This wasn’t simply a memorial portrait or a family keepsake.

It was a weapon.

Visual testimony deployed in a legal battle against a system that sought to punish a woman for surviving her abuser’s death.

We need to find out what happened to them after the hearing, Sarah said.

Whether Catherine and Rose managed to build the life without fear that Catherine promised in court.

Patterson nodded.

The photograph came from a collection sealed in 1953.

Someone saved it deliberately for over 60 years.

Maybe someone who knew what it represented.

Sarah turned the photograph over again, reading the inscription with new understanding.

Mrs.

Katherine O’Brien and daughter Rose.

Simple words that concealed years of suffering, a violent death, a murder investigation, and a custody battle, all resolved by two women’s courage, and one carefully staged photograph.

“Let’s find out what became of them,” she said quietly.

Sarah and Patterson drove to LOL the following week.

The Boot Cotton Mills Museum occupied one of the massive brick structures that had once employed thousands.

The museum archivist Daniel Reeves pulled employment ledgers documenting workers from 1890 to 1900.

Here’s Rose O’Brien, Sarah said, finding her entry.

Hired as a weaver in March 1889, age 16.

Wage $4.50 per week.

Still employed through June 1892.

Patterson scanned Catherine’s records.

Katherine O’Brien spinner hired February 1882.

She’d been working there eight years when Patrick died.

He paused, reading a notation.

She took 3 weeks on paid leave in March 1890, right during the murder investigation.

She couldn’t work while being investigated, Sarah said quietly.

Daniel pointed to another entry beside Catherine’s name in April 1890.

Return to work.

Wage reduced to $4.50 a week due to extended absence.

They punished her financially, Patterson said, anger in his voice.

Even after she was cleared, even after winning the custody case, the mill penalized her for the disruption to their production schedule.

Sarah calculated quickly.

$450 per week for Catherine and maybe $5 for Rose.

950 total.

That’s about $40 per month, barely enough for room, board, and basic necessities.

They were living on almost nothing.

The records showed both women working steadily through 1891 and 1892.

The entries were repetitive.

Hours worked, wages paid, occasional notations about production quotas met or missed.

Then in January 1893, Rose’s entry changed dramatically.

Employment terminated.

Reason marriage Patterson found the corresponding marriage record in a separate database.

Rose O’Brien married James Sullivan January 14th, 1893 at St.

Patrick’s Church in Lel.

James Sullivan’s occupation was listed as railroad breakman.

Skilled labor that paid significantly better than textile work.

She escaped the mills, Sarah said, feeling genuine relief despite the 131 years separating her from these events.

She found someone to marry and got out.

But Catherine’s record continued year after year.

She worked at the boot mills through 1895, then transferred to the Appleton Mills in 1896, then to the Lawrence Mills in 1899.

Each entry tracked her movements through Lel’s textile industry, like a prisoner’s record tracking transfers between institutions.

[music] Daniel pulled out wage records showing the financial reality.

Look at this.

Catherine never earned more than $5 per week.

In 13 years of continuous work after Patrick’s death, she never received a significant [music] raise.

She was still making the same wage in 1903 that she’d made in 1890.

Because she was Irish, female, and had been suspected of killing her husband, Patterson said bitterly.

That reputation would have followed her from mill to mill, management would have seen her as troublesome, unreliable, potentially violent.

Sarah found Catherine’s final entry in the employment records.

December 1905, age 49.

Employment terminated.

Reason injury.

The injury report was clinical and brief.

Katherine O’Brien, spinner, right hand severely damaged and spinning frame malfunction during night shift.

Unable to continue work, no compensation provided as [music] incident deemed result of worker inattention.

Sarah closed her eyes, imagining the reality behind those cold words.

A woman approaching 50, worn down by 23 years of factory labor, losing her hand to machinery, and then losing her livelihood immediately afterward.

No disability payments, no pension, no support.

Sarah searched city directories and census records to discover Katherine’s fate after the injury.

The 1906 Lowel directory provided the answer.

Katherine O’Brien listed his border at the home of James and Rose Sullivan, 22 Cedar Street.

“Rose took her in,” Sarah said, relief flooding through her.

After everything Catherine did to keep them together in 1890, Rose made sure her mother was cared for when she could no longer work.

Patterson found the 1910 census record.

The Sullivan household included James Sullivan, aged 38, railroad breakman, Rose Sullivan, aged 37, housewife, three children aged 8, six, and four, and Katherine O’Brien, age 54, listed as mother-in-law, widowed, no occupation.

The census recorded additional details.

The family lived in a rented house with six rooms, modest, but significantly better than the boarding houses where Katherine and Rose had lived during their mill years.

James Sullivan’s annual income was listed as $780, equivalent to about $15 per week, three times what Katherine had earned at her peak.

Rose married well, Patterson observed.

Not wealthy, but stable, skilled labor with steady income, and she used that stability to provide for her mother.

Oh, Sarah found school enrollment records for the Sullivan children.

Mary Sullivan, age 8, enrolled at the Moody School.

Katherine Sullivan, age six, enrolled at the same school.

James Sullivan Jr., Age four, not yet school age, Rose had named her second daughter Catherine, honoring her mother while giving the name a fresh start, free from the violence and suspicion that had shadowed the original Catherine’s life.

Daniel pulled out one more document from the archives, a death certificate from 1918.

Katherine O’Brien, aged 62, died of pneumonia at the home of her daughter, Rose Sullivan, on March 4th, 1918.

The informant was listed as Rose Sullivan, who had provided details of her mother’s life.

Born County Cork, Ireland, 1856.

immigrated to America 1878, widowed 1890, survived by one daughter and three grandchildren.

Sarah photographed the certificate, noting what was absent.

No mention of the murder investigation, no mention of the custody battle, no mention of Patrick’s violence, or the years of abuse Catherine had endured.

Just the simple facts of immigration, work, motherhood, and death.

History erases the hard parts, Patterson said quietly.

Official records show Catherine as just another Irish immigrant who worked in the mills and died old.

But we know she was so much more.

This Sarah thought of the photograph, the bruises on Catherine’s wrists, the determination in Rose’s face, the legal documents held visibly in frame.

That image had preserved what official records never would.

The story of a woman who survived her abuser, fought off murder accusations, battled in court to keep her daughter, worked her body to destruction, and was finally cared for by the daughter she’d protected.

The photograph was her testimony.

Sarah said the only testimony that survived intact.

Everything else was buried in legal files or erased from family memory.

But that image, that one moment captured in April 1890, preserved the truth.

They gathered all the documents and returned to Boston.

Sarah knew they had found something extraordinary, but she wasn’t sure yet what to do with it.

That evening, she sat in her apartment studying the enhanced digital image.

She had been looking at this photograph for weeks, but it felt different now, understanding who these women really were and what they had endured.

The photograph wasn’t just evidence, it was resistance.

Sarah decided to search for living descendants.

Rose Sullivan had lived until at least 1918 when she’d reported her mother’s death.

If Rose had survived beyond that, there might be grandchildren or great-grandchildren still alive who could provide family stories that official records never captured.

She started with genealogy databases tracing the Sullivan family forward.

Rose and James had four children total.

Mary, born 1902, Catherine, born 1904, James Jr.

born 1906, and Margaret born 1909.

Patterson helped track the children through marriage records and city directories.

Mary Sullivan had married Robert Thompson in 1923 and moved to Worcester.

Katherine Sullivan had married William Hayes in 1925 and remained in Lel.

James Sullivan Jr.

had died in France during World War I in 1918.

Margaret Sullivan had married Henry Cartwright in 1930.

Cartwright,” Sarah said suddenly, the name triggering recognition.

“That sounds familiar.” She pulled out her notes from weeks ago when they’d first started researching the photograph.

The wooden crate containing the photograph had come from a 1953 donation to the historical society.

Sarah flipped through her photographs of the donation records.

The donor’s name written in faded ink.

Estate of Margaret Cartwright, Dorchester, Massachusetts.

Margaret Sullivan married Henry Cartwright, Sarah said, her pulse quickening.

And when she died in 1953, her estate donated this photograph to the historical society.

She kept it her entire life, 63 years after it was taken.

Patterson was already searching online.

Margaret Cartwright’s obituary, Boston Globe, November 1953.

Survived by two daughters, Helen Cartwright Morrison and Ruth Cartwright Coleman.

Sarah’s hands shook as she cross- referenced the names.

Helen Morrison would be in her 70s now if she was still alive.

She searched death records.

[music] No entry for Helen Morrison, born around 1925 to 1930.

Then she found a current listing.

Helen Morrison, age 75, residing at Beacon Hill Retirement Community, Boston, Massachusetts.

“She’s alive,” Sarah whispered.

Katherine O’Brien’s granddaughter is alive.

Patterson stared at her.

“We need to contact her.

She might know family stories.

She might know why her grandmother kept the photograph all those years.” Sarah found a phone number for the retirement community.

Her heart raced as she dialed.

A receptionist answered and Sarah explained she was a curator researching a historical photograph that might be connected to one of the residents.

Helen Morrison.

Yes, she’s one of our residents.

Very sharp, wonderful woman.

Would you like me to leave a message? Please tell her that Sarah Mitchell from the Boston Historical Society has information about a photograph of her great great grandmother, Katherine O’Brien, from 1890.

I’d very much like to speak with her if she’s willing.

The receptionist promised to pass along the message.

Sarah hung up, hardly daring to hope.

3 hours later, her phone rang.

This is Helen Morrison.

A clear, strong voice said.

You called about my great great grandmother.

About a photograph from 1890.

Sarah’s throat tightened.

Yes, Mrs.

Morrison.

We found a photograph of Katherine O’Brien and her daughter Rose taken in Lel in April 1890.

It was donated to the historical society by your mother’s estate in 1953.

I’ve been researching the story behind it, and I’d very much like to speak with you about what we’ve discovered.

There was a long pause.

Then Helen said, “I know that photograph.

My grandmother Margaret showed it to me when I was a little girl.

She told me it saved their lives.

Can you come see me? I have stories you’ll want to hear.

Two days later, Sarah and Patterson sat in Helen Morrison’s apartment at the Beacon Hill Retirement Community.

Helen was 75.

Sharpeyed and elegant with photographs covering every surface of her small living room.

My grandmother Margaret died when I was 22.

Helen began pouring tea with steady hands.

But before she died, she told me things about our family that she’d never told anyone else.

She said, “I was old enough to understand and someone needed to know the truth.” Sarah set up her laptop, showing Helen the enhanced digital scan of the photograph.

Helen’s eyes filled with tears.

“There they are,” she whispered.

“Catherine and Rose.” “My grandmother told me Catherine was the strongest woman she’d ever known, that she’d survived a monster and protected her daughter against everyone who tried to take her away.” “What did your grandmother tell you?” Patterson asked gently.

Helen took a breath.

She told me that Catherine’s husband Patrick was a drunk who beat her regularly.

That Rose grew up terrified of her own father.

That when Patrick died in a factory accident, everyone suspected Catherine had pushed him even though she hadn’t.

She told me about the investigation about Patrick’s brother trying to take Rose away, about the court hearing where Catherine and Rose testified about years of abuse.

Sarah nodded.

We found all the legal records, the murder investigation, the custody petition, the hearing transcript.

Your great great-grandmother was remarkably brave.

Uh, [gasps] my grandmother said Catherine told her that the photograph was what saved them, Helen continued.

The judge kept looking at it during the hearing.

He said it showed her respectable mother and devoted daughter.

The photographer, what was his name? Thomas Mercer, [music] Sarah replied.

Yes, Mercer.

My grandmother said he was kind to them, that he understood what they needed the photograph for, and he made sure to capture them in a way that would convince the judge.

He positioned Rose’s hand on Catherine’s shoulder, just so.

He made sure their morning dresses looked proper and dignified.

He even suggested Rose hold the custody petition in the photograph so the judge could see they weren’t trying to hide anything.

Patterson leaned forward.

Did your grandmother say anything about what happened after the hearing? Helen smiled sadly.

Catherine worked in the mills for another 15 years until she lost her hand in an accident.

Rose married my great-grandfather James and took Catherine in to live with them.

My grandmother Margaret was the youngest of their four children born in 1909.

She remembered her grandmother, Catherine, clearly said she was quiet, had only one hand, but was always kind to the children.

She died when my grandmother was 9 years old.

“Your grandmother kept the photograph all her life,” Sarah said.

“Why did she donate it to the historical society?” Helen stood and retrieved a small wooden box from her bedroom.

Inside was a letter yellowed with age written in careful script.

“My grandmother wrote this in 1953, just before she died,” Helen explained.

She left it with the photograph when she donated it.

I found it among her papers years later.

Listen, I’m donating this photograph to the historical society so that it will be preserved.

It shows my grandmother, Katherine O’Brien, and my mother, Rose Sullivan, as they appeared in 1890, just after my grandmother was investigated for murdering her abusive husband, and just before she fought in court to keep my mother from being taken away by cruel relatives.

This photograph saved their lives.

It convinced a judge that my grandmother was a respectable woman worthy of keeping her daughter.

It preserved their dignity in a moment when the world sought to destroy them.

I want this image preserved so that someday someone will look at it and understand what women endured in that era and how they fought back with whatever tools they had.

My grandmother was not a victim.

She was a survivor and this photograph proves it.

Sarah wiped tears from her eyes.

Your grandmother understood exactly what this photograph represented.

Helen nodded.

She wanted the truth preserved.

even if she couldn’t tell it publicly in 1953.

She knew someday someone would look closely enough to find the story hidden in that image.

The bruises on Catherine’s wrists, Patterson said, the legal document in Rose’s hands, the tension in their faces.

Your grandmother trusted that eventually someone would see.

And you did, Helen said simply.

After 70 years, you found the truth she wanted preserved.

Sarah looked at the photograph on her screen.

Catherine and Rose frozen in that April moment in 1890, holding themselves with dignity despite everything they’d endured.

The photograph had done its work in court, convincing a judge to let them stay together.

And now, 134 years later, it was doing its work again, revealing a story of survival that official records had tried to bury.

“Would you give us permission to tell this story publicly?” Sarah asked.

“To create an exhibition about your great great-grandmother and what this photograph really represents.” Helen smiled.

That’s exactly what my grandmother would have wanted.

Tell everyone.

Tell them what Katherine O’Brien survived.

Tell them how she fought back.

Tell them that this photograph wasn’t just a portrait.

It was a weapon she used to protect her daughter.

Tell them the truth.

6 months later, the Boston Historical Society unveiled an exhibition titled Survivors, Domestic Violence, and Legal Resistance in Industrial America.

The centerpiece was the 1890 photograph of Katherine and Rose O’Brien displayed alongside the court transcripts, medical records, and uh Helen Morrison’s testimony about her grandmother’s memories.

The exhibition didn’t sensationalize the abuse or the murder investigation.

Instead, he contextualized Katherine’s story within the broader reality of women’s lives in industrial era America, showing how domestic violence was endemic, how legal systems often failed to protect victims, and how women developed strategies of resistance using whatever tools were available, including photography.

On opening night, Helen Morrison stood before a crowd of historians, domestic violence advocates, and descendants of Irish immigrant families, and spoke about her great great-grandmother.

Katherine O’Brien was beaten by her husband for years, Helen said, her voice strong.

When he died, she was investigated for murder.

When she was cleared, his relatives tried to take her daughter away.

She fought back with testimony, with character witnesses.

And with this photograph, she won.

She kept her daughter.

She worked her body to disability to provide for her family.

And when she could no longer work, the daughter took care of her until she died.

That’s the story this photograph tells.

That’s the truth my grandmother preserved.

That’s why we’re all standing here tonight, because one woman refused to be destroyed, and one photograph proved she deserved to survive.

The audience was silent, moved.

Sarah watched from the side of the gallery as visitors approached the photograph, reading the detailed panels, studying Catherine’s bruised wrists, examining Rose’s protective stance.

She thought about how easily the story could have been lost, buried in sealed archives, dismissed as just another old family portrait, forgotten entirely.

But Margaret Sullivan Cartwright had understood the photograph’s importance.

She’d kept it for 63 years and then donated it with instructions that someone someday would uncover the truth.

And now finally, Katherine O’Brien’s survival was recognized not as a shameful secret, but as an act of courage that deserved to be remembered.

As the exhibition closed for the evening, Sarah took one last look at the photograph.

Catherine and Rose stared back across 134 years, their secret finally revealed, their strength finally honored.

Sometimes Sarah thought the most powerful testimony is the one that takes more than a century to be heard.

But when it finally speaks, it changes how we understand everything that came before.

Katherine O’Brien had survived.

The photograph proved it.

And now everyone knew.