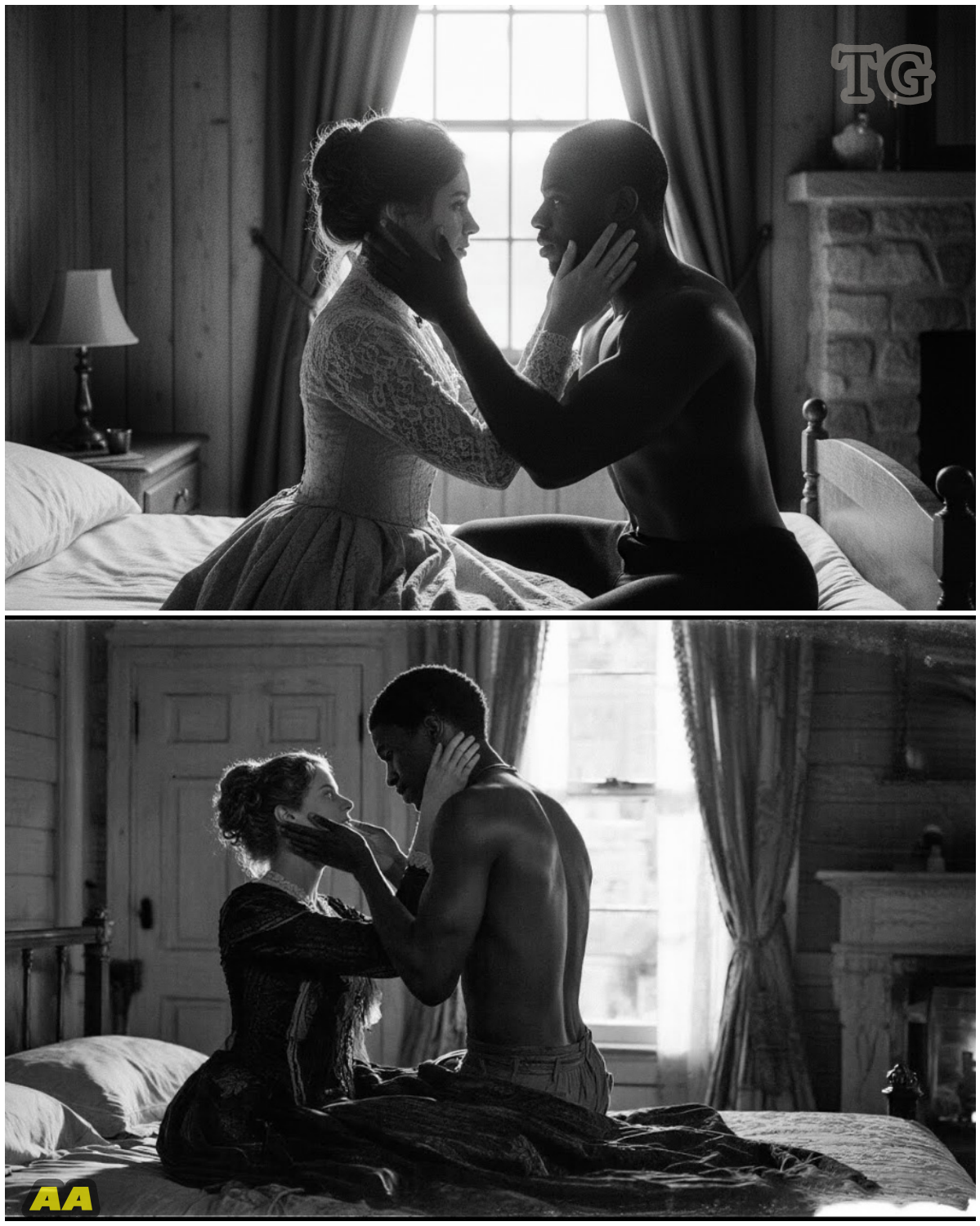

The Impossible Mystery of the Slave Who “Eliminated” 250 White Men — And Was Never Seen Again

They did not say killed at first.

That word came later.

At the beginning, the whispers only said ruined.

I heard the story in a candlelit room where men spoke softly, as if the walls could remember.

“They lost their land,” one man said.

“Their fortunes,” another added.

“Their names,” a third whispered.

And at the center of it all was one enslaved man no one could properly describe.

“He never lifted a weapon,” an old clerk told me, tapping ash from his pipe.

“Then how did 250 men fall,” I asked.

He looked at me with tired eyes.

“By telling the truth.”

Court cases collapsed.

Ledgers vanished.

Wills were rewritten.

Families fled north in shame.

Every time someone tried to find him, he was already gone.

A different plantation.

A different name.

The last person who claimed to see him swore the man smiled and said, “I was never invisible.

You just never looked down.”

Some say he was hunted.

Others say he walked away free.

I did not believe the number at first.

Two hundred and fifty sounded like folklore.

Like a drunken exaggeration whispered to scare children into obedience.

But then I saw the records.

Or rather, I saw the holes where records should have been.

County ledgers with pages sliced cleanly out.

Court dockets that skipped years as if time itself had been bribed.

Family trees with entire branches scratched over in darker ink.

“Every gap leads back to him,” the archivist murmured.

She would not say his name.

No one ever did.

Instead, they described him in fragments.

A man who read without being taught.

A man who remembered conversations verbatim years later.

A man who listened more than he spoke, and when he did speak, asked only one question.

“Why is this written differently here?”

That question, I learned, was how it always began.

On a plantation outside Natchez, a bookkeeper laughed when the enslaved man pointed to a discrepancy.

“You don’t understand numbers,” the bookkeeper said.

The man nodded.

But he remembered.

Months later, a visiting creditor asked why the cotton yield did not match the ledger.

The bookkeeper blamed illness.

The ledger blamed itself.

The plantation collapsed under audit within the year.

One man gone.

No blood.

No bodies.

Just ruin.

In Virginia, the story repeated with a lawyer who specialized in estates.

The enslaved man worked as a stable hand.

But he overheard everything.

“I heard you promise her the land,” he told the lawyer one night, quietly, while brushing a horse.

The lawyer laughed.

“You heard wrong.”

But when the widow testified, her words matched his memory exactly.

The lawyer disbarred himself before the verdict could be read.

Another man erased.

They began to notice a pattern.

Not publicly.

Never publicly.

Men spoke of it at dinners, behind fans, inside closed carriages.

“There is someone,” one whispered.

“A ghost,” another said.

“A devil,” a third insisted, because devils are easier to blame than truth.

Slave catchers were sent.

Pinkertons before they were called that.

Men with dogs and papers and the confidence that the law was always on their side.

They never found him.

Because he did not run.

He moved through.

He changed names the way other men changed coats.

Isaac.

Thomas.

Eli.

Names borrowed, then returned untouched.

One plantation owner swore he owned him for six months.

Another swore it was two years.

When they compared notes, the timelines overlapped impossibly.

“That’s not possible,” one said.

But the ledgers disagreed.

What terrified them was not that he exposed crimes.

It was that he did not seem angry.

A woman who cooked in the big house told me she once asked him why he did it.

“Why them,” she said.

He looked at her and replied,

“I don’t choose them.

They choose themselves.”

The deeper I dug, the clearer it became.

He targeted no one.

He simply listened.

Every man who fell had committed a quiet sin he believed no one would ever question.

Forged signatures.

Stolen inheritances.

Illegal sales.

Murder hidden as accident.

The enslaved man never accused directly.

He only placed truth where it could no longer be ignored.

A misplaced letter.

A remembered date.

A sentence repeated word for word under oath.

And once truth entered the room, men destroyed themselves.

By the time his legend reached South Carolina, some families preemptively fled.

Sold land.

Burned documents.

Changed surnames.

“If he comes,” one man reportedly said, “we’ll already be gone.”

But that did not save them.

Because truth, once spoken, travels faster than people.

The most chilling account came from a judge.

A judge.

He claimed the man appeared in his chambers late one evening to deliver a message.

No threats.

No demands.

Only one sentence.

“Tomorrow you will remember the case from ten years ago differently.”

The judge laughed.

The next day, while reviewing files, his memory returned.

Not changed.

Corrected.

By the end of the month, he resigned.

That made forty-seven.

Then eighty-three.

Then one hundred and twelve.

The newspapers never connected the dots.

They reported isolated scandals.

Individual disgraces.

A sudden epidemic of moral failure among powerful men.

But enslaved people talked.

Quietly.

Carefully.

They called him The Listener.

Some called him The Counter.

One woman called him The Mirror.

“Men look at him,” she said, “and see themselves clearly for the first time.

”

As the number grew, so did the fear.

Rewards were offered.

Dead or alive.

Yet no violence ever followed him.

Not from him.

That was the strangest part.

Plantations burned themselves down through panic.

Families turned on each other.

Brothers accused brothers.

He simply walked on.

The last confirmed sighting occurred in 1860.

A clerk in Baltimore swore a man matching the descriptions asked him for paper.

“What for,” the clerk asked.

“To write nothing down,” the man replied, smiling.

After that, the trail vanishes.

Some say he boarded a ship north.

Others insist he crossed west, beyond records.

A few believe he never existed at all.

But the numbers remain.

Two hundred and fifty men who once held power.

Two hundred and fifty names that stopped appearing after a certain point.

Two hundred and fifty stories that end abruptly, without explanation.

No graves.

No monuments.

Just absence.

When I asked the archivist what she believed, she closed the ledger gently and said,

“Slavery trained people to watch.

To remember.

To survive quietly.”

She looked at me.

“Imagine what happens when someone uses that skill against the system itself.”

I still think about his final words, reported by three different people in three different states.

Each swore he said the same thing.

“I am not your reckoning,” he told them.

“I am your memory.”

And perhaps that is why he was never seen again.

Because memory does not need a body.

It only needs witnesses.

And once awakened, it never goes back to sleep.