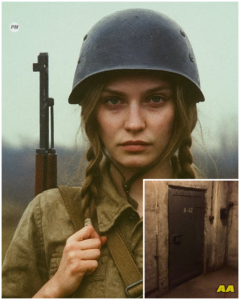

On October 28th, 1944, 13 American soldiers entered a German bunker designated A42 near the Belgian border to investigate reports of medical experiments.

Only one came out alive.

The sole survivor, a nurse turned operative known as the ghost, emerged after 6 hours covered in blood and refused to speak about what happened inside.

3 days later, she vanished completely.

The army declared her killed in action.

sealed the bunker with concrete and classified all records for 50 years.

But in 1994, when an elderly woman named Dorothy Mills died in Indianapolis, her granddaughter discovered a hidden room containing 43 photographs of dead Nazi officers taken between 1945 and 1952, detailed surveillance records, and a journal that began with one line.

My name was Ruth Hawthorne.

I was the ghost.

I didn’t die in that bunker.

I found something that made me disappear.

What Ruth Hawthorne discovered in bunker A42 would reveal why America’s deadliest female soldier chose to vanish at the height of her legend and why she spent the next 50 years hunting everyone who knew what was really hidden in that underground tomb.

September 15th, 1944.

Field Hospital 7 outside Nancy, France.

Ruth Hawthorne had been awake for 36 hours straight, her hands steady despite the exhaustion as she changed dressings on wounds that would haunt her dreams.

Two years as an army nurse had taught her to function on no sleep, to smile while boys died in her arms, to stay calm when the shells fell close enough to shake dust from the ceiling.

She was adjusting Private Morrison’s morphine drip when she heard the trucks.

“Sounds like resupply,” Dr.

Harrison said without looking up from surgery.

About time.

But Ruth had learned to read the sound of engines like music.

These were wrong.

Too fast.

Too many coming from the German side of the line.

Doctor.

The doors burst open.

SS soldiers, 12 of them.

Weapons drawn but casual, like they were walking into a cafe.

Their commander was young, maybe 25, with a scar through his left eyebrow and eyes that looked through people rather than at them.

“We need medical supplies,” he said in accented English, holding a clipboard.

“Morphine, sulfa, bandages.

” Harrison stepped forward, still in his surgical gown.

“This is a Red Cross facility.

You have no authority.

We have all the authority we need.

” The commander studied his clipboard, then looked at the beds.

But first, we have a list to complete.

He walked to the nearest bed.

Sergeant Williams from Ohio.

Shrapnel wounds.

3 days post surgery.

The commander checked the name against his list, nodded to himself, and shot Williams in the head.

The sound was impossibly loud.

Patients who could move tried to scramble away.

Those who couldn’t just stared as the commander moved to the next bed.

Stop.

Harrison rushed forward.

The commander didn’t even look at him, just nodded to one of his men.

A knife appeared.

Harrison’s throat opened in a neat line.

He fell to his knees, hands trying to hold his life in, his eyes finding Ruth across the room.

“Hide!” he mouthed with the last of his breath.

Ruth backed into the supply closet, her body moving without her mind’s permission.

Through the door’s crack, she watched them work through the ward with terrible efficiency.

23 wounded Americans, 23 names on a list, 23 shots.

Morrison tried to crawl under his cot with his one good arm, leaving a trail of blood from his reopened wounds.

They shot him twice, once to stop him, once to finish him.

He’d been 19, from a farm in Iowa.

He’d shown Ruth pictures of his girl back home.

The executions took 12 minutes.

Then they loaded medical supplies while one soldier whistled a tune Ruth recognized.

Lily Marleene.

Another made a joke in German.

His friend laughed.

They left as casually as they’d arrived.

Ruth waited 20 minutes before emerging, though every second felt like betrayal.

The ward was silent except for blood dripping somewhere onto the floor.

She moved bed to bed, checking for life she knew she wouldn’t find.

Under Morrison’s cot, his rifle lay where he’d hidden it against regulations.

He’d been trying to reach it.

His fingers had scratched grooves in the floor.

Ruth picked it up.

She’d never fired a weapon her father had tried to teach her once, but she’d said she was meant to save lives, not take them.

The rifle was still warm from Morrison’s body heat.

Outside, she could hear Allied vehicles approaching.

They’d find the massacre, write reports, send telegrams to families.

The SS unit would disappear into the chaos of the German retreat, unless someone followed them.

Now Ruth looked at Harrison’s body, at Morrison’s scratched fingers, at the 23 boys who’d survived Normandy and Market Garden, only to be executed in their beds.

The rifle in her hands weighed 8 lb.

It felt like nothing at all.

She found the SS tracks easily.

They hadn’t bothered to hide them.

12 men in a truck heading northeast toward the German lines.

The rain was starting, but she could still follow.

Her father had taught her to track deer in the Pennsylvania woods.

This wasn’t much different, except deer didn’t execute wounded boys.

Three miles from the hospital, she found them.

They’d stopped in a bombed out village to divide the medical supplies.

Through the rifle scope, Morrison had kept it perfectly maintained.

She could see them clearly.

the commander smoking a cigarette.

The one who’d whistled, still whistling, the one who’d killed Harrison, cleaning his knife.

Ruth had never wanted to kill anything in her life.

But Ruth had died in that hospital, hand pressed over her mouth to muffle her breathing while boys she’d promised to save were murdered.

What lay behind this rifle scope was something else.

Something that would soon make the Vermach whisper about a ghost that hunted them through the French countryside.

She steadied the rifle against a broken wall, found the commander in her sights, and discovered she knew exactly where to place the shot.

Not the head, too quick.

The stomach just below the vest.

Painful, slow, time enough to be afraid.

Time enough to know death was coming for what they’d done.

Her finger found the trigger.

Morrison had shown her pictures of his girl.

Williams had a son he’d never met.

Harrison had been teaching her surgical techniques just that morning.

She squeezed smooth and even like her father had tried to teach her with the rifle she’d refused to shoot.

The commander dropped, hands clutching his stomach, mouth open in surprise.

The others scrambled for cover, but Ruth was already moving.

Her second shot caught the Whistler in the chest.

The third took the knife cleaner through the throat.

Nine left.

She had 47 rounds, more than enough.

September 20th, 1944, 5 days after Field Hospital 7, Ruth Hawthorne no longer existed in any meaningful way.

The woman wearing her uniform had tracked the SS unit for 3 days through the French countryside, learning their patterns, their weaknesses.

Nine men left.

They’d split up after the village, thinking it would make them safer.

It had just made them easier to hunt one at a time.

She’d found the first two at a checkpoint, shaking down French civilians for food.

They never heard her coming.

Two shots from 300 yd through their helmets.

The civilians had scattered, terrified, never seeing who had saved them.

The third had been relieving himself against a tree when she found him.

She’d used the knife that time, the same one that had killed Harrison.

It seemed fitting.

He’d died gurgling, confused, probably never understanding why.

Six left.

Ruth watched them now from a church bell tower.

The remaining SS soldiers holed up in a farmhouse they’d commandeered.

They were nervous.

She could see it in how they moved, how they checked windows, how they startled at sounds.

They knew they were being hunted.

Good.

Through Morrison’s scope, she studied their faces.

One looked like her cousin back home, young, blonde, worried.

He kept checking his rifle, touching a photo in his pocket.

But she’d watched him execute Corporal Davis, shooting him twice when once would have done it.

Her cousin’s face didn’t matter, only what he’d done.

The radio beside her crackled.

She’d taken it from the checkpoint.

German voices increasingly panicked.

They were reporting the deaths, calling for reinforcements, warning about an American sniper team operating behind lines.

Team.

They thought she was a team.

She’d started leaving something at each scene.

a playing card from Morrison’s pocket.

He’d been teaching the other patients poker.

Now his cards marked the dead.

The two of hearts on the checkpoint bodies, the three of clubs on the one by the tree.

The Germans were calling her deargeist.

The ghost.

The farmhouse below had two entrances, three windows, one chimney.

The smart thing would be to wait for them to leave.

Pick them off in the open.

But Ruth had stopped doing the smart thing when she’d picked up Morrison’s rifle.

She climbed down from the tower as the sun set, moving through the tall grass the way her father had taught her to stalk deer.

Heel to toe, test the ground, shift weight slowly.

The rifle across her back, Harrison’s knife in her hand.

The guard at the back door was smoking the cherry of his cigarette.

A beacon in the darkness.

He was humming.

Not Lily Marlene this time.

Something else.

something that might have been beautiful if his hands weren’t stained with the blood of 23 Americans.

The knife went in under his ribs, angled up, her hand over his mouth to muffle the sound.

He dropped, eyes wide with surprise.

She left the four of diamonds on his chest.

Five left.

Inside she could hear them talking.

Her German was limited, but she understood enough.

They were discussing whether to stay or run.

One wanted to report to command.

Another said command was gone.

Everyone was retreating.

The blonde one, who looked like her cousin, was saying they should have killed the nurse, too.

That leaving a witness was stupid.

Ruth stood in the doorway, Morrison’s rifle raised.

“You did kill the nurse,” she said in English.

They spun toward her, weapons reaching, but she was already firing.

The blonde one first threw the photo he’d been touching in his pocket.

The next two, before they could aim, the fourth, as he tried to dive through a window, the last one, the youngest, maybe 18, dropped his weapon and raised his hands.

“Please,” he said in broken English.

“Please, I was following orders.

” “I didn’t want Did Morrison beg?” The boy’s face crumpled.

He knew the name, remembered.

“Did he beg when you shot him while he was crawling?” I I had to.

They would have shot me if Ruth shot him in the knee.

He screamed falling.

She walked over, stood above him as he writhed.

Morrison was 19, from Iowa, had a girl named Betty who wrote him every week.

She shot the other knee.

Williams had a son he never met.

Davis was going to be a teacher.

The boy was sobbing now, begging in German.

Ruth didn’t understand the words, but understood the tone, the same tone 23 Americans had used.

Dr.

Harrison was teaching me to save lives.

She raised the rifle.

You taught me something else.

One shot.

Silence.

She left the five of spades on his chest and walked out into the night.

It was September 20th, 1944.

In 5 days, she’d killed 11 of the 12 SS soldiers from Field Hospital 7.

The 12th, she’d learned later, had been killed by a random artillery shell while fleeing.

But Ruth didn’t know that yet.

Didn’t know the OSS was already tracking her kills, that German command was starting to panic about Dgeist, that she’d already become something larger than herself.

All she knew was that Morrison’s rifle still had rounds, and there were more SS units out there, more men who executed the wounded, more monsters wearing uniforms.

She found an abandoned barn and made camp.

No fire.

Fire drew attention.

She ate cold rations taken from the farmhouse and cleaned the rifle by touch in the darkness.

Morrison had kept it pristine.

She owed him the same attention to detail.

Her hands were perfectly steady.

No shaking, no tears.

Those would come later, years later, when she was Dorothy Mills teaching Sunday school and would suddenly remember the boy who looked like her cousin begging on his knees.

But that was later.

Now she was learning what she was good at, what she was maybe born for.

The next morning, she found another SS unit.

This one was bigger.

20 men retreating toward the German border.

They’d stopped to rest in a destroyed village.

Through the scope, she could see them eating breakfast, unaware that death was watching from the ruins of a school.

20 men.

She had 36 rounds, more than enough.

Ruth settled into position, finding that perfect stillness her father had tried to teach her.

The place where breathing slowed, heartbeat steadied, and the world narrowed to what was visible through the scope.

the commander first, then the radio operator, so they couldn’t call for help.

Then work through them methodically, like checking patients on rounds.

Just a different kind of rounds now.

She squeezed the trigger.

By noon, 17 were dead.

The last three had fled into the woods.

She tracked them for 2 hours, following broken branches and bootprints, until she found them trying to hide in a ditch.

They surrendered, threw down their weapons, hands up, shouting words she didn’t understand, but recognized his please.

Ruth thought about Morrison crawling under his bed.

Harrison trying to protect his patients.

23 Americans who’d gotten no mercy.

Three shots, three cards, the Jack, Queen, and King of Hearts.

That night, the German radio frequencies erupted with warnings about Dergeist, a single American operative who never missed, never stopped, never showed mercy.

Command was pulling units back from isolated positions, afraid to leave small groups vulnerable.

One person, one nurse with a rifle, and the German army was reorganizing its retreat patterns to avoid her.

Ruth listened to their panic on the stolen radio and felt something she hadn’t expected.

Satisfaction.

Not pleasure, not joy, but the cold satisfaction of a job being done well.

She was very good at this, better than she’d been at nursing.

And there were so many more SS units between her and Germany, so many more monsters who needed to meet their ghost.

Tomorrow, the OSS would find her.

Tomorrow, they’d offer her a choice, court marshal or cooperation.

Tomorrow, she’d officially become their weapon.

But tonight, she was just Ruth Hawthorne, sitting in the dark, cleaning Morrison’s rifle and planning how to kill more efficiently.

The nurse was dead.

The ghost was just beginning.

October 1st, 1944.

OSS, forward operating base outside Mets.

47 confirmed kills in two weeks, the handler said, spreading photographs across the table.

Each showed a dead German officer with a playing card placed on the body.

You’ve terrified them more than our entire offensive.

Ruth stood at attention in her mismatched uniform, still the nurse’s insignia, but now with a rifle she never put down.

The handler, who’d introduced himself only as control, was studying her like she was a specimen.

They’re pulling entire units back from forward positions, he continued, scared of one woman with a rifle.

I’m not finished.

No, you’re not.

He pulled out a folder.

Which is why we’re making you official.

No name, no unit designation, just operational clearance to hunt behind enemy lines.

And if I refuse, then you’re a deserter who abandoned her post during a massacre.

Court marshall, possible execution.

He lit a cigarette.

But we both know you won’t refuse.

You like what you’ve become.

Ruth said nothing.

He was wrong.

She didn’t like it.

But she was good at it.

Better than good.

Perfect.

There’s an SS medical unit operating near here, control said, sliding her a map.

They’ve been collecting specific prisoners, taking them somewhere designated A42.

We need to know what they’re doing.

You want me to follow them? I want you to do what you do.

Thin their ranks.

Make them panic.

Maybe one will talk before dying.

Ruth studied the map.

The area was heavily forested.

Perfect for ambush equipment, whatever you need.

But you work alone.

No backup, no support.

You’re a ghost after all.

October 3rd, 1944.

Woods outside Mets.

Ruth had been watching the SS medical convoy for 2 days.

Three trucks, 12 guards, four medical personnel.

They had stopped at a temporary camp processing prisoners, but not normal prisoners.

They were taking children, French, Belgian, even some German children, ages 8 to 14, all healthy, all terrified.

Through the scope, she watched them examining the children like livestock, measuring skulls, checking eyes, taking blood samples.

One doctor, older with wire- rimmed glasses, was making notes in a leather journal.

She’d already identified their pattern.

Guards changed every 4 hours.

The medical staff slept in the middle truck.

The children were kept in the rear vehicle, locked in but unguarded between midnight and 4:00 a.

m.

Tonight, she’d start.

The first guard never heard her coming.

The knife, she’d gotten good with the knife, slipped between his ribs while he was lighting a cigarette.

She left the ace of spades on his chest.

The death card.

The second guard at the other end of the camp took a bullet through the temple from 200 yd.

suppressed rifle control had given her.

Quiet enough that no one woke.

Two down, 10 guards left, plus the medical staff.

She moved through the camp like smoke, placing small charges control had provided.

Not enough to destroy the trucks, but enough to cause chaos.

Then she positioned herself on a ridge overlooking the camp and waited for dawn.

The guards found the bodies at sunrise.

Panic erupted.

Shouting in German, weapons drawn.

Everyone scrambling for cover.

That’s when Ruth triggered the charges.

Small explosions, more sound than damage, but enough to make them think they were under full assault.

In the chaos, she started shooting.

The radio operator first.

No calls for help.

Then the officer trying to organize resistance.

Then two guards who broke cover trying to reach better positions.

Seven left, plus the medical staff.

They tried to flee in the trucks, but she’d anticipated that.

Shot out the tires on the first vehicle, causing it to crash and block the road.

The guards spilled out, firing blindly into the forest.

She picked them off methodically, one trying to flank her position, another attempting to reach the radio in the crashed truck.

A third who thought hiding behind a tree would save him.

The bullet went through the tree and through him.

Four left.

That’s when one of the medical staff emerged from the middle truck, hands raised, waving a white cloth.

Stop, he called in accented English.

We are medical personnel.

Geneva Convention.

Ruth put a bullet at his feet.

He stumbled back.

The children, she called back.

Release them.

We cannot.

They are part of important medical research.

She shot him in the shoulder, spinning him down.

The other medical staff rushed out to help him.

Through the scope, she could see the older doctor with wire rimmed glasses, the one who’d been taking notes.

He was looking directly at her position, though he couldn’t possibly see her.

“You are the ghost,” he called out.

“The one they whisper about.

” Ruth said nothing.

“I am Dr.

Ernst Hoffman,” he continued.

“What we do here is for the advancement of medical science, these children.

” She shot the doctor trying to bandage his colleagueu’s shoulder.

He dropped, clutching his thigh.

Release them, she repeated.

The last two guards tried to rush her position while she was talking.

She’d expected that, too.

Two shots, two bodies rolling down the hillside.

Two more cards to place later.

Just the medical staff left now.

Four men, two wounded.

She emerged from cover, rifle trained on them.

Up close, they looked smaller, older.

afraid.

Dr.

Hoffman was still standing, still studying her with those intelligent eyes.

“You don’t understand what you’re interrupting,” he said.

“Project A42 will change everything.

Human enhancement, disease resistance, the next step in evolution using children.

Children adapt better to the modifications.

Their cells are still growing.

Still Ruth shot him in the knee.

He screamed, falling.

“Where is A42?” “You’ll never find it,” he gasped.

“And even if you do, you can’t stop it.

” “It’s not just German research, your own people.

” She shot his other knee.

“Where?” He was crying now.

“All scientific dignity gone.

Northwest 40 km bunker complex.

But you’re too late.

The experiments are complete.

The subjects are already changing.

” Ruth looked at the truck full of children.

Through the small window, she could see their faces, terrified, confused, some no older than her youngest brother back home.

She unlocked the truck.

“Run,” she told them in broken French.

“Run and don’t stop.

” They scattered into the forest like frightened deer.

The medical staff watched their subjects disappear.

One tried to protest.

Ruth shot him in the stomach, the same place she’d shot the first SS commander weeks ago.

You’re making a mistake, Hoffman gasped from the ground.

Those children could have been the future.

Enhanced humans, stronger, smarter.

They’re children, not experiments.

She went through their documents while they bled.

Maps, medical records, detailed notes about previous subjects.

12 children already at A42 undergoing something called phase 3 modifications.

October 5th, 1944.

Ruth watched the medical convoy burn.

She’d drag the medical staff to safety first, let them live to remember, to spread fear.

Hoffman would survive if help came soon.

The others might not.

She’d placed cards on all the dead guards, two through 10 of spades, saving the face cards for something special.

In two days, she’d eliminated an entire SS medical unit, freed 20 children, and learned about a 42.

Control would want a full report, would want to send a team to investigate, but Ruth looked at the documents she’d taken, the photos of children in surgical beds, and knew she couldn’t wait for official approval.

40 km northwest, a bunker full of children being modified.

She had 60 rounds left.

Morrison’s rifle was still perfect despite everything.

The knife was sharp.

October 6th, 1944.

German radio frequencies were in full panic.

Durggeist had struck again.

Entire units were refusing to operate in small groups.

Officers were demanding transfers away from the region.

One woman, one rifle.

The Vermacht was restructuring its entire defensive position because of her.

But Ruth barely heard the chatter anymore.

All she could think about were those photos.

Children on tables, children in cages.

12 subjects already in phase three, whatever that meant.

She cleaned her rifle in an abandoned church surrounded by shattered stained glass and broken pews.

Tomorrow she’d start hunting toward A42.

Control had promised her backup when she found it.

A full squad to assault the bunker.

She didn’t believe him.

The OSS liked her working alone, liked their ghost being singular, mysterious, deniable.

But that was fine.

She’d gotten used to being alone, gotten used to the weight of Morrison’s rifle, the feel of Harrison’s knife, the sound of German panic on stolen radios.

The nurse was long dead.

The ghost was heading for A42.

And God help anyone who stood between her and those children.

October 15th, 1944.

10 kilometers from A42, Ruth lay in mud that smelled of rot and cordite, watching the SS checkpoint through her scope.

Six guards, one officer, a machine gun nest.

They were checking everyone passing through, even their own vehicles.

She’d been hunting toward A42 for 9 days, leaving a trail of bodies that had German command in full panic.

23 more kills.

The Jack, Queen, and King of Spades left on officers, the other suits for regular soldiers.

But this was different.

These guards weren’t standard Vermach.

They wore SS Medical Corps insignia, the same as Hoffman’s unit.

They were protecting something specific.

Through the scope, she watched a supply truck approach.

The guards checked papers, then something else.

They made the driver and passenger roll up their sleeves, examining their arms for something.

Ruth pulled back into the forest to think.

In her pack, she carried the documents from Hoffman’s convoy.

One mentioned security protocols for A42, special identification, tattoos that couldn’t be forged.

She needed one of those guards alive.

That night, she waited for the shift change.

One guard always walked into the woods to relieve himself.

Clockwork every 4 hours.

She’d watched for two days, learning their patterns the way her father had taught her to learn deer trails.

He was young, maybe 20, humming as he unbuttoned his trousers.

The knife was at his throat before he could cry out.

“Scream and die,” she whispered in broken German.

“Nod if you understand.

” He nodded, trembling.

She zip tied his hands, American Ingenuity Control had called them, and dragged him deeper into the woods.

In the darkness, his terror was palpable.

A 42, she said.

Tell me.

He babbled in German, too fast for her to follow.

She pressed the knife harder.

English kind.

She cut him just enough to draw blood.

English now, please.

Small English.

The bunker.

Medical kinder.

Children.

She understood that word.

How many? He held up both hands, then two fingers.

12.

She pulled out Hoffman’s papers, pointed to the photos of children in surgical beds.

These? He nodded frantically.

Ya ya experiments.

Burbesser.

She didn’t know that word, but his tone said enough.

Whatever they were doing to those children, even the guards were disturbed.

The tattoo, she said, pointing to his arm.

Show me.

He rolled up his sleeve, revealing a small medical kaducius with numbers beneath.

She memorized it, then considered her options.

Kill him and take his uniform, but she was too small to pass for a male guard.

Let him live and risk him alerting others.

She zip tied his ankles, gagged him, and left him tied to a tree.

He’d be found at shift change, but she’d be past the checkpoint by then.

October 16th, 1944.

Dawn.

Ruth had smeared mud on her face, dirtied her uniform beyond recognition.

Just another refugee on the road.

The rifle was hidden in a burial shroud she’d taken from a destroyed church.

Just another person carrying their dead.

She approached the checkpoint with others fleeing the fighting.

Old women, children, a few wounded soldiers.

The guards were checking everyone, but casually.

They weren’t expecting their ghost to walk up in daylight.

Papierre, the guard demanded.

She produced the papers she’d taken from a dead nurse weeks ago, keeping her head down, shoulders hunched.

Just another exhausted medical worker.

He barely glanced at them, then grabbed her arm.

Mal sleeve.

He wanted to see her arm.

She rolled it up, showing nothing.

He frowned, called to the officer.

Ruth’s hand drifted to the knife hidden under the burial shroud.

The officer approached, studied her.

Medical personnel? She nodded.

“Which unit?” She pointed to her throat, mouththing words without sound, mute from trauma.

She’d seen enough shell shocked nurses to mimic the symptoms.

The officer’s expression softened slightly.

Another one broken by the war.

He waved her through.

“The medical convoy left an hour ago.

You’ll have to walk.

” She nodded gratefully, shuffled past with her wrapped body.

3 km beyond the checkpoint, she retrieved her rifle and disappeared into the forest.

The bunker was close now.

She could feel it like a weight in the air.

October 17th, 1944.

Ruth found A42 at sunset.

It didn’t look like much.

A concrete entrance built into a hillside camouflaged with vegetation.

Two guards at the door, bored, smoking.

A radio antenna suggested underground communications.

Tire tracks showed regular vehicle traffic.

She circled the perimeter, finding ventilation shafts and emergency exit, what looked like a pre-war drainage tunnel sealed with a metal grate.

Multiple entry points, but all guarded or secured.

Through binoculars, she watched the shift change.

12 guards total, rotating in 4-hour shifts.

Medical staff came and went.

She counted six doctors, unknown number of support personnel.

And once just before dark, she saw them.

Children at a window, three faces, pale, eyes hollow.

One had bandages around his head.

Another’s arm was in a sling that looked wrong.

The angle suggested the arm was longer than it should be.

Ruth felt the familiar cold rage settle in her chest.

The same feeling from Field Hospital 7, but refined now.

Focused.

She set up position on the ridge, plotting angles, counting distances.

The smart play was to wait for controls backup.

12 guards plus interior security was too much for one person.

But those children were in there now, suffering now.

She’d watched 23 Americans die while she hid in a closet.

She wouldn’t hide again.

October 18th, 1944.

2 a.

m.

The drainage tunnel’s grate was 60 years old, rusted.

Ruth’s stolen bolt cutters taken from the checkpoint, cut through in minutes.

The tunnel was narrow, partially flooded, smelling of decay.

She crawled through darkness, rifle wrapped in oil cloth on her back.

The tunnel opened into a mechanical room.

Boilers, water pumps, the guts of the facility, no guards.

Why guard a sealed tunnel? She moved through the basement, following pipes and electrical lines upward.

The building was larger than it appeared, three levels underground, maybe more.

She heard voices above, German, casual conversation.

A stairwell led up.

She climbed slowly, testing each step.

The first suble was storage, medical supplies, food, equipment.

The second suble made her stop.

An observation window looked into a surgical theater.

Inside, a child lay on a table, maybe 10 years old, unconscious, tubes running into his arms.

Two doctors worked over him, their hands bloody to the elbows.

They were putting something into his chest cavity, something mechanical.

Ruth raised her rifle, but the window was reinforced glass, bulletproof.

She could only watch as they worked precise and careful, like they were fixing a machine instead of torturing a child.

One doctor looked up directly at the window.

Ruth ducked, but he wasn’t looking at her, just checking the observation room clock.

They finished, began closing the incision.

She had to move.

Had to find the other children before footsteps in the stairwell.

Multiple sets coming down.

Ruth slipped into a supply closet as four guards passed, escorting a doctor she recognized from the photos.

Hoffman had mentioned him.

Dr.

Kger, the project director.

The new subjects arrive tomorrow.

He was saying 12 more for phase 4.

Will the current subjects survive? One guard asked.

Three will.

Perhaps four.

The modifications are intense, but those who survive will be.

Remarkable.

They entered the surgical theater.

Ruth waited until their voices faded, then continued up.

The main level was administrative, offices, communications, a small barracks.

She counted six guards, two awake, four sleeping.

The medical staff quarters were separate down another hallway.

But where were the children? She found them on the third suble, the deepest part of the bunker.

12 cells, each with a small window.

Nine were occupied.

The children inside were wrong.

One girl’s eyes reflected light like a cat’s.

A boy’s hands had too many joints.

Another child sat in the corner rocking, his skin modeled with patches that looked almost like scales.

Experiments, modifications, horrors that would have been called impossible if she wasn’t seeing them.

At the end of the hall, a larger cell, three children together, the ones who looked most normal.

They saw her through the window, eyes widening.

One started to speak.

Ruth put a finger to her lips.

Silence.

She tried the door, locked, of course.

The keys would be with the guards, but she couldn’t take 12 guards alone.

Not in close quarters, not without killing the children in crossfire.

She needed them to come to her, needed to thin their numbers.

October 18th, 1944.

300 a.

m.

Ruth placed Hoffman’s medical notes at the main entrance, waited with a playing card, the ace of hearts.

Then she retreated to her ridge position and waited.

Dawn brought the shift change.

The new guards found the documents, the card.

Panic erupted.

Radio calls, officers running, everyone focused on the security breach.

They sent out search parties.

Four guards in one group, three in another, leaving only five inside.

Ruth let the first group pass, then opened fire on the second.

Three shots, three bodies.

The survivors scattered, calling for backup.

The four guard group rushed back, firing wildly into the forest.

She was already moving, circling to their flank.

Morrison’s rifle sang its familiar song.

Two more down before they found cover.

Reinforcements poured from the bunker.

Exactly what she’d wanted.

The interior was emptying.

Guards rushing to defend against an external threat.

She counted.

Nine guards outside now, spread across the hillside, hunting for her.

Three, maybe four still inside.

Time to move.

The drainage tunnel was still clear.

She crawled through again, emerging in the mechanical room.

Above, she could hear running, shouting.

The skeleton crew inside was trying to coordinate the search outside.

She climbed to the third suble to the children.

The guard at the cell block never heard her coming.

Harrison’s knife, quick and quiet.

She took his keys, began opening cells.

Schnel, she whispered.

Quiet.

Follow.

Some children couldn’t walk properly.

Their modifications had damaged their legs, their balance.

Others were too traumatized to understand.

But the three normall-looking ones helped, supporting the others, following her toward the tunnel.

They’d made it to the second suble when Dr.

Kger appeared at the top of the stairs.

For a moment, they just stared at each other.

him in his white coat, her in her muddy uniform, nine broken children between them.

He reached for an alarm button.

Ruth shot him through the wrist, then the shoulder, spinning him down.

The gunshots echoed through the bunker.

No point in stealth now.

Run, she told the children who could.

The tunnel go.

Guards were coming.

She could hear boots on stairs, weapons being readied.

She pushed the children toward the mechanical room, then turned to face what was coming.

Three guards rounded the corner.

Ruth dropped two before they could aim.

The third got a shot off.

Pain bloomed in her side, but she stayed standing.

Fired back.

He fell.

More coming.

Always more.

She backed toward the tunnel, firing at shadows, at movement, at anything that might be a threat.

Her ammunition was running low.

Five rounds left, maybe six.

The children had made it to the tunnel.

The older ones were helping the modified ones through, but it was slow.

Too slow.

A guard appeared in the doorway.

Ruth fired, missed, her first miss since taking Morrison’s rifle.

The pain in her side was spreading, her vision starting to blur.

The guard aimed, and his head exploded.

Control stood in the opposite doorway, smoking pistol in hand.

Behind him, American soldiers poured into the bunker.

Cutting it close, ghost, he said.

The children.

We’ve got them.

Medical teams are waiting outside.

He looked at her side, the spreading blood.

You’re hit.

I noticed.

Why didn’t you wait for backup? Ruth thought about the 23 Americans at Field Hospital 7, about hiding in that closet, about Morrison crawling under his bed.

I don’t wait anymore, she said, and collapsed.

October 28th, 1944, 10 days after the first assault on A42.

Ruth stood outside the bunker again, her side still bandaged but healing.

Control had wanted her in a hospital.

She’d refused.

The bunker hadn’t been fully cleared.

Lower levels remained unexplored, sealed doors unopened.

Command wanted to wait for specialized teams, but the children who’d survived had whispered about others, deeper, hidden.

The special ones, they’d said in broken English, the ones who screamed.

12 soldiers stood with her.

Harper, Wilson, Patterson, good men who’d volunteered despite knowing about the ghost’s reputation.

They’d all heard the stories.

the nurse who never missed, who never stopped, who terrified the Vermacht into restructuring their entire defensive line.

“Stay behind me,” she told them.

“Don’t touch anything.

Don’t open doors without my signal.

” They entered through the main entrance this time.

The bodies had been removed, but blood still stained the concrete.

Ruth led them past the administrative level, past the surgical theaters, past the cells where nine children had been kept.

At the back of the third suble, they found it.

a heavy door marked with biohazard symbols and one word srehandling special treatment.

The lock was sophisticated, but Harper had been a safe cracker before the war.

20 minutes of delicate work and it clicked open.

The smell hit them first.

Chemicals and something else.

Something organic and wrong.

Wilson vomited.

Patterson crossed himself.

Ruth pushed through.

The room beyond was massive, carved from living rock.

Laboratory equipment lined the walls, filing cabinets full of documents, and in the center, 12 glass tanks filled with murky fluid.

Things floated in those tanks.

They had been children once.

She could see that in the basic shape, the size.

But what had been done to them? One had arms that stretched too long, joints bending in impossible directions.

Another skull had been opened and expanded.

Brain tissue visible through transparent panels.

A third looked normal until you noticed the gills sliced into its throat, the webbing between its fingers.

“Jesus Christ,” Harper whispered.

Ruth approached the nearest tank.

The thing inside opened its eyes.

Human eyes aware, terrified.

“Alive! They were all alive.

” She found the control panel, the documents explaining the system.

The children were in suspended animation, kept barely conscious, their modified bodies preserved in chemical solution.

Some had been there for months.

The pain must have been.

Ghost controls voice from behind.

She hadn’t heard him arrive.

We need to document everything.

This is evidence of war crimes.

They’re alive.

They’re experiments.

Valuable intelligence about German research.

Ruth turned and control stopped talking.

Something in her face perhaps or the way her hand had moved to Morrison’s rifle.

“We’re getting them out,” she said.

“Ghost, be reasonable.

Look at them.

They can’t survive outside the tanks.

Even if we could extract them, they’d die within hours.

” She looked at the children floating in hell.

Thought about Private Morrison, 19 years old, crawling under his bed.

About Dr.

Harrison trying to protect his patients.

about hiding in a closet while 23 Americans died.

“Then they die free,” she said.

“I can’t authorize.

” Ruth shot the first tank.

The glass exploded.

Chemical solution flooding across the floor.

The child inside, a boy, maybe 12, with those horrifically elongated arms spilled onto the concrete.

He gasped, coughed, tried to scream, but his throat had been modified, producing only a whistling sound.

Ruth knelt beside him, cradling his twisted body.

“It’s okay,” she lied.

“You’re free now.

” “Stand down!” Control shouted.

“That’s an order.

” She shot the second tank, then the third.

By the fourth, Harper was helping her.

Wilson too.

They caught the children as they fell from their prisons, held them as they gasped in air their lungs weren’t designed for anymore.

Patterson found blankets wrapped the children’s modified bodies.

Some had scales where skin should be.

Others had bones that bent like rubber.

One girl’s eyes had been replaced with compound lenses like an insects.

“What did they do?” Wilson asked, holding a child whose spine curved outside his body.

Ruth found the research notes coded but clear enough.

They were trying to create enhanced soldiers.

Testing how far the human body could be modified and still function.

These 12 were the failures, too changed to be useful, too valuable to dispose of.

Monsters, Patterson said.

Childhren, Ruth corrected.

They were children.

One by one, the 12 died.

Some within minutes, their modified bodies unable to function outside the chemical suspension.

Others lasted hours fighting for each breath.

Ruth held each one learned their names from the German documentation.

Klouse, age eight, modified for underwater operations.

Marie, age 10, neural enhancements that had destroyed her motor functions.

Hans, age 13, attempted bone reinforcement that had turned his skeleton to something like rubber.

She memorized each name, each face, each modification.

These weren’t statistics or intelligence.

They were children who’d been tortured in the name of science.

Control stood in the doorway, radio in hand.

Command wants this facility secured.

The research here could advance our own medical programs by decades.

No ghost.

My name is Ruth Hawthorne.

She stood, Morrison’s rifle in her hands.

I was a nurse at Field Hospital 7.

I watched 23 Americans die.

I’ve killed 91 Germans in 6 weeks.

And I’m telling you, this ends here.

She moved through the laboratory, shooting equipment, destroying documents.

Harper and the others joined her, smashing computers, burning files.

Control screamed about court marshal, about treason, about valuable intelligence lost.

In the last filing cabinet, Ruth found something that stopped her cold.

American letterhead OSS signature dated 1943.

It was a cooperation agreement.

The Americans had known about A42 had been receiving reports were planning to acquire the research after German defeat.

You knew she said to control his face was stone.

War requires difficult choices.

You knew they were experimenting on children.

We knew they were conducting enhancement research.

the specifics.

Ruth shot him in the knee.

He screamed, falling.

The other soldiers raised their weapons, unsure who to aim at.

The war is almost over, Ruth said, standing over control.

Germany’s finished.

But this, whatever this is, it’s just beginning, isn’t it? You want to continue the research? Use what they learned.

Control, gasping through pain.

You don’t understand what’s at stake.

The Soviets have their own programs.

If we don’t advance, we’ll be left behind.

By torturing children, by understanding human potential.

He struggled to sit up.

Your proof it works.

Your shooting, your ability to track, to hunt, your enhanced ghost.

The hospital massacre exposed you to their aerosol test.

You’re one of them.

Ruth went cold.

What? Why do you think you never miss? Why? You can track targets like an animal.

The exposure changed you.

Made you into the perfect killer.

He laughed through his pain.

You’re not hunting monsters.

You are the monster.

Ruth looked at her hands.

Steady.

Always steady.

Even now with this revelation, no trembling.

She thought about the past 6 weeks.

91 kills.

Never missed once except when she was wounded.

Could track anyone through any terrain.

Not natural.

Not normal.

enhanced.

“Maybe I am a monster,” she said, “but I’m not your monster.

” She destroyed the rest of the facility, every document, every piece of equipment, every sign that A42 had ever existed.

The 12 dead children were wrapped in American flags, the closest thing to dignity she could give them.

As they emerged from the bunker, Ruth made a decision.

“I died in there,” she told Harper and the others.

Ruth Hawthorne entered bunker A42 and didn’t come out.

That’s what you’ll report.

Ghost.

There is no ghost.

Never was.

Just a story to scare Germans.

She looked at each of them.

Those children deserve justice, but they’ll never get it.

The best I can do is make sure this never happens again.

She gave Harper her dog tags, Morrison’s rifle, everything that identified her as Ruth Hawthorne or the ghost.

What will you do? Wilson asked.

Ruth thought about the American documents, the implication that A42 was just one of many programs.

The war might be ending, but something worse was beginning.

What I’m good at, she said, hunt monsters.

But now I know they don’t all wear German uniforms.

She walked into the forest, leaving 12 good soldiers to report that the ghost had died destroying a German research facility.

control wounded would tell a different story.

But who would believe him? The ghost was a legend, not a person.

Ruth Hawthorne was officially dead.

But something else walked out of those woods.

Something enhanced, something angry, something that would spend the next 50 years hunting anyone connected to projects like A42.

In a week, she’d be in Switzerland creating a new identity, Dorothy Mills.

In a year, she’d be in Argentina hunting the first of 43 Nazi scientists who’d fled there.

In 5 years, she’d be married, pretending to be normal, using suburban life as cover for her real work.

But that was all to come.

On October 28th, 1944, the ghost died in Bunker A, 42, and Dorothy Mills, the woman who would become America’s most dangerous secret, was born.

November 15th, 1944.

Switzerland.

Ruth Hawthorne no longer existed.

The woman in the Zurich bank was Dorothy Mills, war widow, late of Ohio.

Her papers were perfect.

Control might have been a bastard, but the OSS forggers were artists.

She deposited the gold teeth and wedding rings she’d taken from SS officers.

Blood money, but it would fund what came next.

The bank manager didn’t ask questions.

Swiss banks never did.

In her hotel room, she studied the documents she’d saved from A42.

Not the enhancement research.

She’d burned that, but the personnel files, names, photographs, home addresses of everyone involved.

43 doctors and researchers who tortured children in the name of science.

The war would end soon.

These men would disappear into the chaos, emerge with new names, new lives, unless someone stopped them.

She started a journal.

The work continues.

Ruth died in that bunker, but her skills live on.

I am Dorothy Mills.

Now I will be whoever I need to be.

March 8th, 1945.

Lake Ko, Italy.

Dr.

Friedrich Vber thought he was safe.

The war was ending.

Germany collapsing.

He’d burned his uniform, grown a beard, taken a job as a village doctor.

who would look for a war criminal healing Italian farmers.

Dorothy had been watching him for three days.

He was good at his new job, gentle with patience, kind to children.

It would have been easier if he’d remained a monster.

She waited until he was walking home alone, late after delivering a baby.

The knife went in clean between his ribs, angled up to the heart.

He dropped his medical bag, turned to see his killer.

“You,” he gasped in German, “the ghost.

” But you died.

Ruth died.

I’m someone else now.

I saved children, too.

After the war, I’ve saved.

You experimented on 12 children at A42.

I held them while they died.

She let him fall, placed a playing card on his chest, the Ace of Spades, and disappeared into the night.

The local police would find him in the morning, assume it was revenge for collaboration.

They wouldn’t investigate too hard.

One down, 42 to go.

May 7th, 1945, VE Day.

The world celebrated.

Dorothy sat in a cafe in Baron, watching people dance in the streets.

The radio announced Germany’s unconditional surrender.

The war in Europe was over, but not her war.

She’d killed four more from her list in the past two months.

Each one had thought themselves safe, hidden, reborn.

Each one had recognized her.

At the end, the ghost was becoming a different kind of legend.

Not the Vermach sphere, but the nightmares of escaped war criminals.

An American officer sat down at her table uninvited.

She recognized him.

OSS, one of Control’s subordinates.

“Miss Mills,” he said carefully.

“Or should I say, Dorothy Mills, war widow, traveling to cope with grief.

” Of course.

He slid a folder across the table.

Some friends thought you might find this interesting.

Passenger manifests.

Ships leaving for South America.

Amazing how many German doctors suddenly need to immigrate.

She didn’t touch the folder.

I don’t know what you mean.

The agency has interests in some of these men.

Scientific knowledge that could benefit America, but others, well, others have no value.

It would be convenient if those others never reached their destinations.

I’m just a widow traveling.

Control is dead.

Infection from his knee wound.

Tragic.

The officer stood.

Enjoy your travels, Mrs.

Mills.

I hear Argentina is lovely this time of year.

After he left, Dorothy opened the folder.

15 names from her list, all booked on the same ship.

traveling together for safety, thinking numbers would protect them.

They were wrong.

July 18th, 1947.

Buenos Cyrus.

Dorothy had been in Argentina for 2 years, establishing herself as a grieving widow who’d come to start over.

She taught English, volunteered at the local church, baked for neighbors.

Everyone knew sweet, sad Dorothy Mills.

No one connected her to the 18 German immigrants who’ died of heart attacks, accidents, or suicide since 1945.

Hans Mueller was next.

She’d saved him for special attention.

He’d been the lead researcher on the children’s modifications.

He lived well in Buenosiris, practicing medicine under a false name, protected by the network of escaped Nazis who called themselves the organization.

She followed him for months, learning his routine, his guards, his weaknesses.

He had a daughter now, 8 years old, the same age as Marie, the girl whose brain he’d exposed at a 42.

Dorothy watched the girl play in the park while Mueller sat on a bench reading.

A loving father, a monster.

Both things true at once.

She could have killed him there, one shot from distance or a knife in the crowd.

But that would leave his daughter traumatized.

Blood on her dress, nightmares forever.

Dorothy had become death.

But she wasn’t cruel.

Not to children.

She waited three more days until Müller was alone at his clinic, working late.

No guards, no witnesses.

He was reviewing patient files when she entered.

Hair Miller.

He looked up, confused.

Then recognition, then terror.

You’re dead.

The ghost died at A42.

Ghosts don’t die, they haunt.

He reached for a gun in his drawer.

She was faster.

Morrison’s training even without Morrison’s rifle.

The gun skittered across the floor.

My daughter will grow up without you, but she’ll grow up.

Unlike Marie, unlike Hans, unlike the 12 children you tortured, I was following orders.

It was war.

The war’s been over for 2 years.

She gave him a choice, the knife or poison.

He chose poison, begging her to make it look natural for his daughter’s sake.

She agreed.

The death certificate would say heart attack.

His daughter would grieve a father, not a monster.

That small mercy was all she could offer.

September 3rd, 1952.

S.

Paulo, Brazil.

Dorothy sat in her apartment cleaning a pistol she’d taken from her latest target.

41 down, two left, seven years of hunting and almost done.

A knock at the door.

She had the gun up before the second knock.

Mrs.

Mills, it’s James Morrison from Indianapolis.

She froze.

That name Morrison like the boy from field hospital 7.

Through the peepphole, she saw a man, early 30s, kind face, holding flowers.

I know this is strange, he said through the door.

But I’ve been looking for you.

My buddy Harper said you knew my cousin Eddie from the war.

Eddie Morrison.

He died in France.

Private Morrison, 19, from Iowa, crawling under his bed.

Dorothy opened the door, gun hidden.

I’m sorry.

You must be mistaken.

Please.

Harper said you were a nurse.

Said you were with Eddie when he died.

The lie came easily after seven years of practice.

I held his hand.

He wasn’t in pain.

James Morrison cried.

This stranger crying for his cousin in her doorway.

She let him in, made coffee, told comforting lies about Eddie’s last moments.

They talked until dawn.

He was an engineer, had been stationed in the Pacific, was traveling through South America for work.

He was kind, funny, unmarked by the darkness she carried.

“Would you have dinner with me?” he asked as the sun rose.

“I know it’s forward, but I feel like Eddie brought us together.

” Dorothy thought about the 41 men she’d killed.

The two still on her list, the blood that would never wash clean.

Yes, she said, because even ghosts got lonely.

October 15th, 1952.

Buenos Cyrus, the last name on her list, Wilhelm Brener, the administrator who’d requisitioned the children for experiments.

He lived in a fortress of a house, surrounded by guards, paranoid after 7 years of his colleagues dying around him.

Dorothy was 6 months pregnant with James’s child.

They’d married quickly, quietly.

He thought her reticence was grief.

She let him think that.

She climbed the wall at 3:00 a.

m.

moving carefully with her changed center of gravity.

The guards were lazy after years of nothing happening.

She slipped past them like smoke.

Brener was in his study, unable to sleep.

He saw her in the mirror turned slowly.

You’re pregnant.

Yes.

And you still came? A life growing inside me doesn’t erase the 12 who died in my arms.

He looked older, exhausted.

Will it ever end? this hunting tonight and then then Dorothy Mills goes home to Indianapolis, becomes a mother, forgets she was ever anything else.

Can you forget? She thought about that.

7 years of hunting, 42 kills since the war ended.

The weight of it all.

No, but I can pretend.

She made it quick.

He’d been expecting death for 7 years.

That was punishment enough.

She left the last playing card, the ace of hearts, and walked out past sleeping guards.

James was waiting at the hotel, worried.

Where were you? Couldn’t sleep.

Walked to clear my head.

He held her, hands gentle on her swollen belly.

Come home with me to Indianapolis.

Let’s raise our family away from all this sadness.

Dorothy Mills nodded, kissed him, let him believe she was just a war widow finding love again.

Ruth Hawthorne was dead.

The ghost was legend.

The hunt was over.

But that night, as James slept, she wrote in her journal.

43 confirmed postwar.

Total count.

134.

The list is complete, but the work may not be done.

Others are out there.

Other programs, other experiments, other monsters.

If they come for my children, I’ll become the ghost again.

But for now, I’ll be Dorothy Mills, suburban mother, Sunday school teacher.

I’ll bake pies and plant gardens and pretend my hands aren’t stained with blood.

The perfect cover for America’s Most Dangerous Woman.

She burned the journal entry, but kept the skills just in case.

March 15th, 1962.

Indianapolis.

Dorothy Mills stood in her kitchen frosting her daughter Catherine’s 10th birthday cake when she saw him through the window.

A man at the bus stop reading a newspaper.

Wrong clothes for the weather.

Wrong posture for a civilian watching her house.

James was at work.

Catherine at school.

Dorothy was supposed to be alone, vulnerable.

She finished the cake, washed her hands, and walked out the back door with a basket of laundry to hang.

The neighbor’s fence provided cover as she circled the block.

10 years of suburbia hadn’t dulled her skills.

The man was still there pretending to read.

She came up behind him, pressed the garden shears she’d grabbed against his kidney.

Move and I open you up right here.

He tensed.

Mrs.

Mills, who sent you? The agency they need Ruth Hawthorne is dead has been since 1944.

There’s a situation.

Nevada children are involved.

Her hands steadied.

Always children.

Talk.

Not here.

There’s a car.

We walk to the park.

You in front.

They walked like old friends.

Her shears hidden in the laundry basket she still carried.

At the park, empty on a Tuesday morning.

She let him sit on a bench.

She remained standing, ready to run or fight.

He pulled out a folder, hands careful and slow.

Project MK Ultra American program using some of the A42 research.

You didn’t destroy.

I destroyed it all.

You destroyed the German copy, but control had already transmitted preliminary findings before you shot him.

He showed her photographs, an underground facility, medical equipment, and children in hospital beds.

Dorothy’s hands went cold.

Where? Nevada test site underground hidden in the nuclear testing program.

The radiation keeps people away.

Perfect cover.

He pulled out more photos.

12 children so far.

Volunteers, they say.

Orphans who won’t be missed.

Just like A42.

Why? Tell me.

Because some of us remember what you did in that bunker.

What control was willing to allow.

Not all of us agree with continuing the research.

But not enough to stop it officially.

No, that’s why we need the ghost.

Dorothy thought about the cake on her counter.

Catherine’s birthday party this afternoon.

James coming home with presents.

10 years of normal life.

I have a family.

We know.

That’s why we’re asking, not ordering.

But Mrs.

Mills, Dorothy, those children have no one else.

She took the folder.

I’ll need things.

Whatever you need.

And when it’s done, you forget I exist.

The agency forgets.

Everyone forgets.

Agreed.

And if anyone comes near my family, the ghost hunts again.

Understood.

March 18th, 1962.

Nevada.

Dorothy told James she was visiting her sick aunt in Chicago.

He kissed her goodbye, told her to be careful.

Catherine hugged her, still happy from her birthday party.

The flight to Nevada felt like traveling backward through time.

The woman in seat 12B was Dorothy Mills, suburban mother.

The woman who walked off the plane was someone else, someone who’d killed 134 people and was ready to add to that count.

The contact met her at a motel outside the test site.

He had equipment, rifle, pistol, knife, credentials that would get her onto the base.

The facility is here.

He pointed to a map.

Sublevel 4 of the medical research building.

Security is tight, but there’s a maintenance tunnel.

I know how to infiltrate a bunker.

He looked at her.

40 years old, graying hair, laugh lines from a decade of pretending to be happy.

You really are her.

The ghost.

No.

I’m a mother who’s very good at certain things.

She entered the base at shift change.

just another nurse reporting for duty.

The credentials were perfect, the uniform authentic.

No one looked twice at a middle-aged woman with kind eyes.

The medical building was new, modern, efficient, nothing like A42’s cramped bunker, but the smell was the same.

Antiseptic and fear.

She took the elevator to suble two, then found the maintenance stairs.

Two more levels down past radiation warnings and restricted access signs.

The country’s nuclear shield hiding its darkest secret.

The door to suble required a key code.

She waited, patient as she’d once waited for German patrols.

20 minutes later, a doctor emerged.

She caught the door before it closed, slipped inside.

The corridor beyond was bright, clinical.

Through observation windows, she saw them.

12 children ages 8 to 14, some in beds, some in testing rooms, all with the hollow eyes she remembered from A42.

But these children weren’t being physically modified.

The experiments were pharmaceutical drugs to enhance memory, reaction time, intelligence, creating super soldiers through chemistry rather than surgery.

Less cruel than A42, but still using children as test subjects.

A doctor emerged from one room, making notes on a clipboard.

Dorothy recognized him, not personally, but the type, the same detached curiosity she’d seen in German researchers.

The ability to see children as data points.

She followed him to his office.

He was alone filing reports when she entered and locked the door behind her.

Excuse me, who are the knife was at his throat before he could finish.

How many children? I don’t.

She cut him.

Just enough to draw blood.

How many? 12 here.

More at other sites.

Other sites.

Of course.

The research data.

Where? Mainframe.

Sublevel 5.

Access codes.

He gave them trembling.

She knocked him unconscious.

Tied him with his own belt and tie.

He’d live, but he’d remember.

Sublevel 5 was server rooms and filing systems.

She found the mainframe, used the codes, file after file of experiment data.

American children being given untested drugs, their reactions cataloged with the same cold precision the Nazis had used.

She began destroying it all.

Magnets for the tape drives, fire for the papers.

20 years of research turning to smoke and damaged circuits.

The alarm started.

Security would come soon.

But first, the children.

She ran back to sublevel 4.

The doors to the children’s rooms were locked electronically.

She shut the control panel and they all opened at once.

Children emerged, confused, scared, some unsteady from the drugs.

“Follow me,” she said in her mother voice, the one that had soothed Catherine through nightmares.

“We’re leaving.

” Security arrived as they reached the stairs.

Three guards, young men just doing their jobs, not knowing what they were protecting.

Dorothy shot them all in the knees.

Painful, crippling, but not fatal.

They’d live.

The children didn’t need to see more death.

They climbed.

Four flights of stairs with drugged children, some barely able to walk.

Dorothy carried the smallest, a girl, maybe eight, who kept apologizing for being tired.

It’s okay, sweetheart.

You’re doing great.

They emerged into chaos.

Alarms blaring, security converging, but also something else.

Military police, FBI, reporters.

Her contact had done more than provide equipment.

He’d blown the whistle.

The children were taken to regular hospitals.

The facility was shut down officially for safety violations.

The real reason would be buried in classified files.

Dorothy slipped away in the confusion.

Just another nurse evacuated from a radiation leak.

March 20th, 1962.

Indianapolis.

She came home to find James cooking dinner.

Catherine doing homework.

Normal.

Perfect.

Safe.

How was your aunt? James asked, kissing her.

Better.

Much better.

That night, after her family slept, Dorothy sat in her basement workshop.

James thought she was refinishing furniture down there.

she wrote in a new journal.

The list continues, “Not Nazi war criminals, but American researchers who’ve forgotten that children aren’t laboratory rats.

I found evidence of six more sites.

The ghost may need to hunt again, but she never got the chance.

” The radiation exposure from the Nevada site from walking through contaminated areas to reach the children had been severe.

The doctors found the cancer 8 months later.

They gave her a year.

She lived for 32 more.

Spite, the doctors called it a miracle.

Dorothy knew better.

She had a daughter to raise, a husband to love, a granddaughter to train.

Death would have to wait.

She taught Catherine to shoot.

Just rabbits, dear.

Taught her to notice everything, remember everyone.

Taught her skills a suburban mother shouldn’t know.

And when Clare was born, Dorothy looked at her granddaughter and saw it immediately.

The same steady hands, the same sharp eyes, the same potential for violence, carefully controlled.

She’d trained Clare, too, better than she’d trained Catherine.

Because Dorothy could feel it in her cancerous bones, the programs hadn’t ended.

They just hidden deeper.

Someone would need to stop them.

Someone would need to be the ghost.

October 28th, 1994, 50 years exactly after A42.

Dorothy Mills died in her sleep, surrounded by family.

Her last words declare, “The basement, behind the water heater, everything you need.

” The obituary mentioned her church work, her apple pies, her devotion to family.

It didn’t mention the 134 confirmed kills.

The 43 Nazis hunted across seven years, the American program she’d destroyed, the children she’d saved.

Ruth Hawthorne had died in 1944.

The ghost was legend.

Dorothy Mills was just a grandmother.

But in the basement behind the water heater, waited the truth.

Photos, documents, weapons, and a list.

Not of the dead, but of those still hunting children.

Still experimenting, still believing humans could be improved through torture.

The ghost was dead.

But ghosts, by definition, never really die.

They just wait for someone new to carry their name.

October 29th, 1994, the day after Dorothy’s funeral, Clare Morrison sat in her grandmother’s basement, surrounded by death.

Not just the photos of 134 corpses, but the weight of understanding.

Dorothy Mills had been America’s greatest secret weapon and its most carefully hidden shame.

At the bottom of the final box, she found an envelope marked, “Open only if they come for you.

” She opened it.

Claire, if you’re reading this, someone at the funeral was watching.

They know who Dorothy Mills really was.

More importantly, they know you have my files.

The real enemy was never the Germans.

It was the idea that humans can be improved through suffering.

That idea survived the war.

It works in our government now.

Run a car pulled up outside.

Then another and another.

Clare grabbed the essentials.

Dorothy’s journal, the Luger, cash hidden in a coffee can.

The rest would have to burn.

She’d prepared for this without knowing it.

All those camping trips where Dorothy had made her practice emergency evacuation drills.

She lit the accelerant Dorothy had stored for refinishing furniture, she’d claimed.

The basement erupted as Clare escaped through the storm doors Dorothy had insisted on installing in 1978.

Three blocks away, watching her childhood home burn, Clare called the only number Dorothy had made her memorize.

It rang once.

Is the ghost walking? A woman’s voice.

Elderly.

The ghost is dead.

But something else is walking.

Tomorrow, noon, Union Station.

Look for the woman with the red scarf.

November 1st, 1994.

Union Station, Indianapolis.

The woman with the red scarf was 70some, moving with the careful precision of someone containing violence.

She didn’t introduce herself, just handed Clare a train ticket.

Your grandmother saved my life in 1962.

I was eight in the Nevada facility.

Clare studied her.

One of the children from Dorothy’s last mission.

You knew she’d die yesterday.

She called me 3 weeks ago.

Said the cancer had won, but she’d lasted long enough.

said someone would come for her files once she was gone.

Who? The same people who’ve always been there.

Operation Paperclip brought 1,600 Nazi scientists to America, not just rocket engineers, biologists, doctors, the ones who’d worked on enhancement programs.

She pulled out a folder.

This is everyone Dorothy identified but didn’t kill.

She was too sick after Nevada.

Clare opened it.

23 names.

American officials who’d protected Nazi researchers continued their work.

Some were senators now.

Others ran corporations.

One was being considered for the Supreme Court.

They can’t all be guilty.

No, but they all know.

They all stayed silent while the research continued.

The woman stood to leave.

Your grandmother killed the ones who acted.

These are the ones who allowed.

You decide which is worse.

December 15th, 1994, Washington, DC.

Clare had spent six weeks researching the names on Dorothy’s final list, following paper trails, financial records, connections.

The woman at Union Station had been right.

They all knew they’d all profited from silence.

But one name stood out.

Director Harold Morrison, no relation, CIA, who’d personally authorized seven black sites where enhancement research continued using volunteer soldiers who didn’t know what they were volunteering for.

He lived in a suburban fortress, all cameras and guards.

But Dorothy had taught Clare that everyone had patterns, weaknesses.

Morrison’s was his weekly visit to his son’s grave.

Korea, 1952.

Every Sunday, dawn alone.

Clare waited in the pre-dawn darkness, Dorothy’s Luger heavy in her pocket.

She could kill him.

One shot like Dorothy would have.

Justice for unnamed victims.

Morrison arrived on schedule, flowers in hand.

He knelt at the grave, head bowed.

The perfect target.

Clare stepped out, gun visible but not raised.

Director Morrison.

He didn’t turn.

You’re Ruth’s granddaughter.

I wondered when you’d come.

Dorothy.

Her name was Dorothy Mills.

Her name was Ruth Hawthorne and she was the finest killer America ever produced.

He stood faced her.

I was at Field Hospital 7.

You know, arrived 3 hours after the massacre.

Saw what she saw.

The difference is I reported it.

She acted on it.

You knew about A42.

We all knew.

We needed to know what the Germans had learned.

War requires terrible choices.

The war ended 50 years ago.

Did it or did it just change shape? He pulled out a photograph.

Children in beds but not suffering.

Laughing.

Playing video games.

Current program.

All volunteers.

Proper medical care.

Enhancement through careful pharmaceutical adjustment, not torture.

Using children, sick children.

Terminal cases.

We offer them hope.

experimental treatments that might save them while advancing human potential.

Clare kept the gun steady.

And if they die, they were dying anyway.

But some alive, some become more than they were.

Like my grandmother.

Morrison smiled sadly.

Your grandmother was an accident.

Aerosol exposure at Field Hospital 7 triggered latent capabilities.

We’ve been trying to replicate it for 50 years.

Never quite succeeded.

So you keep experimenting.

We keep trying to protect America.

The Soviets had their own programs.

Now the Chinese do.

If we don’t advance, we fall behind.

Using children, using volunteers.

Clare thought about Dorothy’s choice.

Kill the monster or become one.

But Morrison wasn’t a monster.

He was worse, a bureaucrat who’d normalized horror.

The names on Dorothy’s list, the ones she didn’t kill.

All good men who made hard choices.

All complicit in continuing Nazi research.

All protecting America from its enemies.

He turned back to his son’s grave.

My boy died in Korea because we didn’t have enhanced soldiers.

How many American boys would have lived if we’d succeeded earlier? Clare could have argued could have pointed out the moral horror of his logic.

Instead, she said Dorothy left more than just names.

She documented everything.

Every program, every facility, every child who died for your research.

I’ve sent copies to 12 major newspapers.

They published tomorrow.

Unless Unless full shutdown, every program, every facility, every experiment ends.

Morrison laughed.

You can’t stop progress with blackmail.

No, but I can expose it.

Let the American people decide if they want their government torturing children for military advantage.

It’s not torture.

Clare shot him in the knee.

He screamed, falling.

She stood over him.

Dorothy’s ghost made flesh.

That’s for every child who died in your programs.

You’ll live.

Walk with a limp.

Remember that Dorothy Mills’s granddaughter could have killed you but chose mercy.

She knelt beside him.

The programs end or the newspapers publish.

You have 6 hours.

She left him there, bleeding but alive.

Dorothy would have killed him.

But Clare had learned something from reading her grandmother’s journals.

The killing never stopped the programs.

It just drove them deeper.

Exposure was the real weapon.

December 16th, 1994.