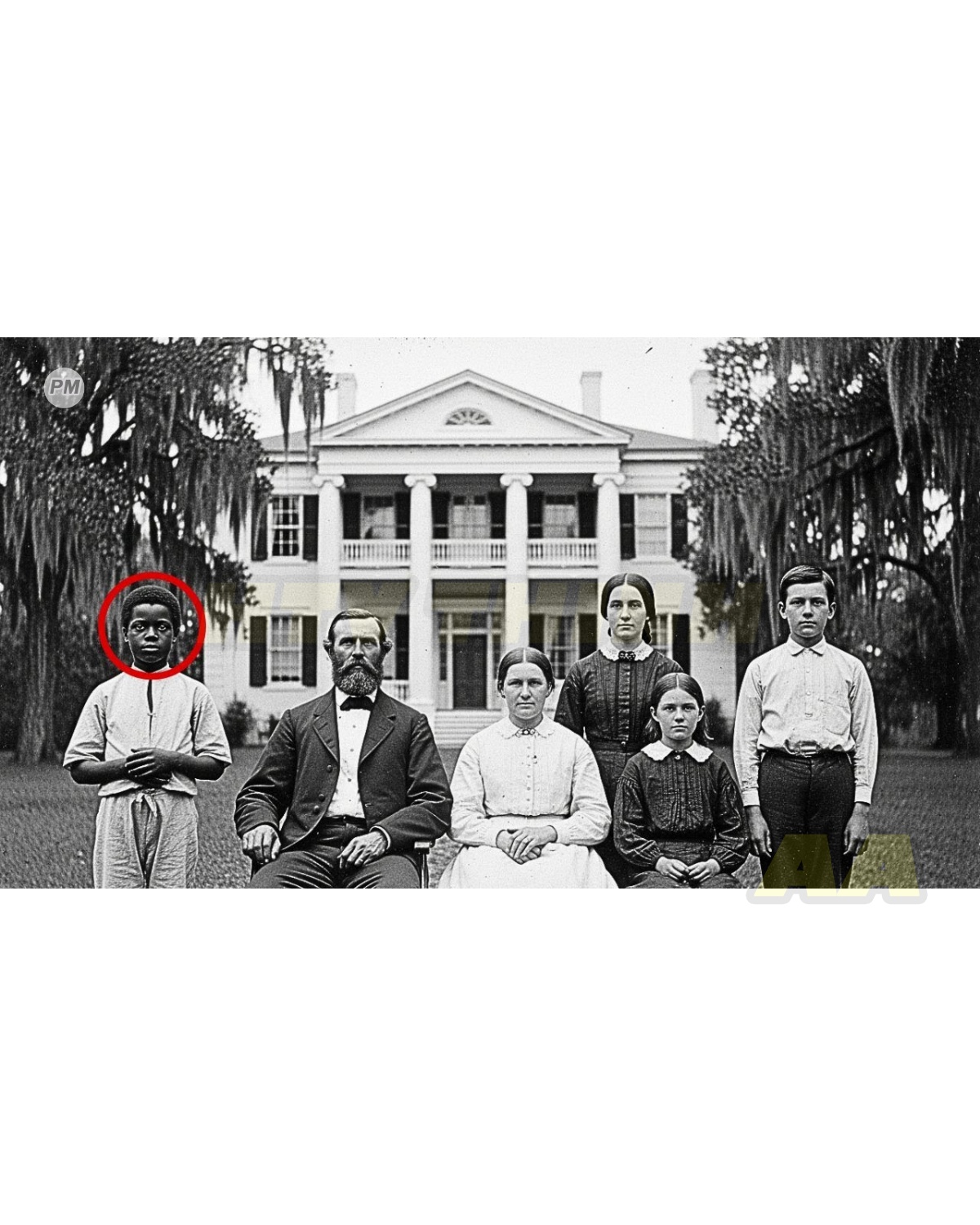

The photograph arrived at the Pennsylvania Historical Society on a gray Tuesday morning in March 2019. Elena Vasquez, a senior archivist with 23 years of experience cataloging the region’s industrial past, opened the package with practiced care. Inside lay a sepia-toned portrait, its edges worn soft by time, depicting a Black family of four standing before a modest wooden house. The image bore the date stamp of a studio in Manonga, West Virginia—a name that made Elena pause. She knew that name. Everyone who studied American labor history knew that name. It was synonymous with tragedy, loss, and the darkest chapter of America’s industrial age.

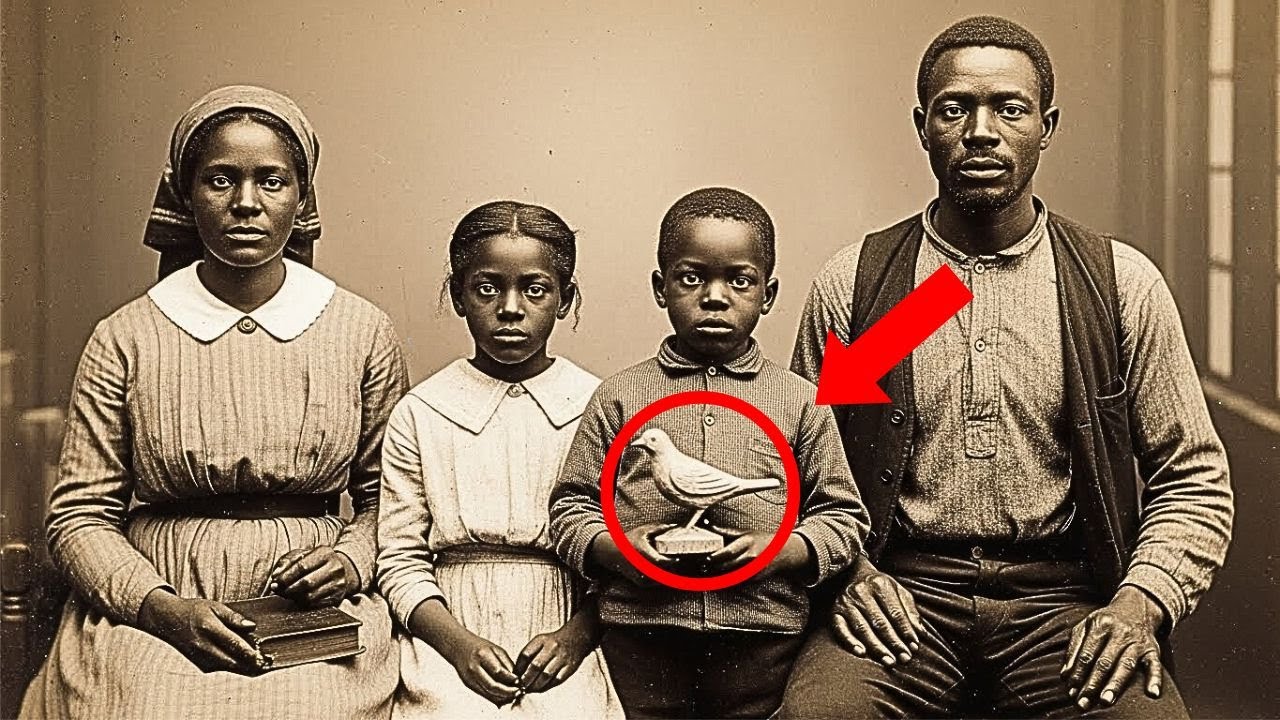

At first glance, the family in the photograph seemed ordinary enough. A stern-faced Black man in work clothes stood beside a woman in a simple cotton dress, her hair wrapped beneath a modest headscarf. Between them stood two children, a girl of perhaps ten years and a boy no older than six. They stared into the camera with the solemn expressions typical of early photography, where long exposure times demanded stillness and smiles were rare luxuries. But something about the image nagged at Elena as she examined it under her desk lamp—something she couldn’t quite identify, something that whispered of secrets buried beneath the surface.

The accompanying letter explained that the photograph had been found in the attic of a demolished home in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, tucked inside a water-damaged Bible alongside pressed flowers and faded prayer cards. The sender, a construction foreman named Michael Torres, had almost thrown it away before noticing the Manonga stamp. His grandmother, a retired school teacher who had dedicated her life to preserving Black history in Appalachia, had told him stories about that town—stories about darkness and fire, about men who never came home, about Black miners whose sacrifices had been erased from official histories.

Elena adjusted her magnifying glass and leaned closer to the photograph. The father’s hands were rough and blackened—miner’s hands, she recognized immediately. Coal dust had a way of seeping into skin, staining it permanently like a tattoo that told the story of a man’s labor. The mother clutched a worn Bible, her knuckles tight with tension that even a century-old photograph could not hide. Her eyes held a sadness that seemed to reach across the decades. But it was the boy that drew Elena’s attention most powerfully. In his small hands, he held what appeared to be a carved wooden bird.

She could make out the shape of wings, a curved beak, the suggestion of feathers etched into the wood with remarkable skill. She made a note in her catalog: “Black family portrait, circa 1912. Manonga, WV. Child holding carved wooden object. Bird. Canary.” The word “canary” made her fingers hesitate over the keyboard. In mining communities, canaries were not simply birds; they were warnings. They were the difference between life and death. And for Black miners in the segregated coal fields of early 20th-century America, they were often the only voice that couldn’t be silenced.

Manonga, West Virginia, in 1912 was a town built on coal and sustained by desperate hope. Immigrants from Italy, Poland, Hungary, and a dozen other nations had flooded into the narrow valley, drawn by the promise of steady work in the Fairmont Coal Company’s mines. Alongside them came Black workers from the Deep South, men fleeing the terror of Jim Crow, the sharecropping traps, and the ever-present threat of lynching. They sought freedom in the coal fields only to find a different kind of oppression waiting in the darkness underground.

They lived in segregated company houses, bought their food at company stores that charged them higher prices, and sent their children to underfunded company schools. Elena spent three days researching the town’s history before she found the first connection to the photograph. Census records from 1910 listed a Black family matching the description: Isaiah, age 34, born in Alabama, listed as Negro; his wife, Bessie, age 29, born in Georgia; their daughter, Ruby, age eight; and their son, Samuel Jr., age four. Isaiah’s occupation was listed as coal loader, one of the most dangerous jobs in the mines, disproportionately assigned to Black workers.

The more Elena learned about Isaiah, the more the photograph began to speak to her. He had been born in 1876 in rural Alabama, just 11 years after the end of slavery. His parents had been enslaved on a cotton plantation, freed by the Emancipation Proclamation, but trapped in poverty by the sharecropping system that replaced bondage with debt. Isaiah had fled north in 1901, part of the early wave of the Great Migration, seeking work and dignity in the industrial heartland. He had labored in steel mills, railroad yards, and finally the coal fields, where a strong back could earn enough to support a family regardless of skin color—or so the company recruiters promised.

Elena found a company record that noted Isaiah’s unexpected skill: “Good worker,” the foreman had written. “Unusually educated for a colored man, makes carvings in spare time.” The notation, dripping with the casual racism of the era, confirmed what Elena had suspected about the wooden bird in the photograph. Isaiah had carved it himself—a canary, the symbol of every miner’s daily gamble with death. But why would a father give such a morbid gift to his young son?

The answer lay buried in the darkest chapter of American industrial history, intertwined with the even darker history of race in America. The payroll records told a story that the official histories had deliberately forgotten. Isaiah’s name appeared on the work schedule for December 6, 1907, the morning of the Manonga mining disaster, when an explosion killed 362 men in the deadliest mining accident in American history. He should have been inside mine number six when the blast ripped through the tunnels at 10:28 a.m. He should have been one of the bodies—many of them unidentifiable, some never recovered, buried in the mass graves that still marked the Manonga cemetery. But he wasn’t. According to the records, Isaiah had been marked absent that day. The notation beside his name read simply, “Did not report. Troublemaker.”

Elena contacted the West Virginia Mine History Association, hoping to find more information. A retired mining engineer named Harold Patterson called her back two days later. His voice was gravelly with age, but his memory remained sharp as a pickaxe. His own grandfather, he explained, had worked as a foreman alongside Black and immigrant miners in the Manonga tunnels. He remembered stories passed down through generations—stories about the days before the disaster when strange and terrifying things had begun happening underground. Stories that had been dismissed, ignored, and ultimately buried alongside the dead.

“The canaries,” Harold said, his voice dropping to a near whisper. “My grandfather said the canaries started dying three days before the explosion, one after another in different sections of the mine. The company replaced them, but they kept dying. Some of the old-timers wanted to stop work, investigate the ventilation systems, but the company refused. Coal had to be loaded. Quotas had to be met. Christmas bonuses depended on production numbers. The dead canaries were written off as coincidence, as bad luck, as anything but what they really were—desperate warnings from creatures that couldn’t speak but tried to save human lives.”

Elena felt a chill run down her spine despite the warmth of her office. “And Isaiah? Do you know why he wasn’t at work that day?”

Harold was quiet for a long moment, and when he spoke again, his voice carried the weight of a century of suppressed truth. “My grandfather told me about a Black carver who tried to warn the others. He tracked the dead canaries, measured the air himself, using methods he’d learned from an old Welsh miner. He carved wooden canaries and gave them to anyone who would listen, telling them to remember what the real birds were saying. Most men laughed at him. Some called him a superstitious fool. The foreman called him a troublemaker, trying to slow down production. But on the morning of December 6, a handful of men stayed home. They trusted the Black carver’s warning when the company told them to ignore it.”

Elena realized that if she could identify those seven men and their descendants, she would have corroborating witnesses to Isaiah’s courage and the company’s criminal negligence. Harold proved invaluable in this search. His grandfather’s journals, passed down through the family like heirlooms, contained names and fragments of stories from the old mining days. Cross-referencing these with census records and company payrolls, Elena identified six of the seven survivors: Antonio from Sicily, Joseph from Poland, Dmitri from Ukraine, Patrick from Ireland, Samuel from Wales, and Giovanni from Naples. The seventh man, another Black miner whose name had been recorded only as George Colored, remained lost to the deliberate erasures of history.

Over the following months, Elena tracked down descendants of five of the six identified families. Each family had preserved its own version of the story, passed down through whispered conversations at kitchen tables, through bedtime stories and funeral eulogies, through half-remembered tales that grandchildren had always assumed were family legends. The details varied—the weather that December morning, the exact words Isaiah had spoken—but the core remained unshakable. A Black carver had warned their ancestors about the danger. He had given them wooden canaries as tangible reminders of the risk. He had saved their lives when no one else would listen.

Giovanni’s great-grandson, a retired firefighter named Michael living in Chicago, still had his family’s wooden canary. It was smaller than the one in the photograph, worn smooth by generations of reverent handling. But the same delicate craftsmanship was unmistakable. The same steady hand, the same artist’s eye, and carved into its breast, hidden among the feathers like a secret prayer, were the same damning numbers: 47 ppm, DEEC 3, ignored.

Elena now had physical evidence from multiple sources. The company had known. Their own inspector had confirmed what Isaiah reported, and 362 men had died because a Black man’s warning didn’t matter to men who valued profit over lives.

The town of Manonga in 2019 bore little resemblance to the bustling mining community of a century earlier. The mines had closed decades ago, victims of changing economics and depleted seams. The company houses had crumbled into vine-covered ruins, their foundations slowly returning to the earth. The population had dwindled from thousands to mere hundreds, mostly elderly residents, too rooted to leave and too poor to restore what time had taken.

But the memorial to the disaster still stood in the town cemetery—a granite obelisk bearing the names of 362 men who had never come home. Elena noticed immediately that no Black names appeared on the stone, though records showed at least 30 Black miners had died in the explosion.

Elena stood before the memorial on a cold November morning, the photograph clutched in her hands like a talisman. She had come to pay her respects, but also to search for any remaining evidence that might corroborate her findings. The local historical society, run by a retired teacher named Dorothy, had agreed to open their modest archives for her research. The society’s collection was small but meticulously organized, the work of decades of dedication.

Dorothy had spent 30 years gathering documents, photographs, and oral histories from the families who had survived the disaster and its aftermath. Among her treasures was a collection of newspaper clippings from December 1907, including an article from the Fairmont Times that mentioned a Negro laborer spreading panic among the workers in the days before the explosion. The article dismissed Isaiah as superstitious and praised the company for maintaining order despite agitation. The racism dripped from every line like poison.

Dorothy also had something Elena hadn’t expected: a photograph of survivors taken in 1908 on the first anniversary of the disaster. Seven men stood in a row before the memorial, dressed in their Sunday clothes, their faces solemn with survivor’s guilt. Each held something small in their hands.

Elena examined the photograph under magnification and felt tears spring to her eyes. Wooden canaries. Every single one of them held a carved wooden canary, their tribute to the man who had saved them. They called themselves the Canary Brotherhood, Dorothy said quietly. “They met every year until the last one died in 1962, and they never stopped saying that a Black man had saved their lives when no one else would listen.”

Elena published her findings in the spring of 2020 in a peer-reviewed article for the Journal of American Labor History titled “The Canary Song: Race, Negligence, and Silenced Warnings in the Manonga Mining Disaster.” The evidence was overwhelming and meticulously documented: company documents proving knowledge of dangerous conditions, inspector reports that had been received and ignored, Isaiah’s dismissed complaint marked “source unreliable,” and six surviving wooden canaries bearing carved testimony to the truth.

The story was picked up by national media within days, spreading across newspapers, websites, and television programs hungry for stories of historical injustice finally exposed. The descendants of the disaster victims responded with a mixture of profound grief and long-awaited vindication. For generations, they had carried the weight of 362 lost lives, never knowing whether their ancestors might have been saved. Now they had an answer and a target for their long-suppressed anger.

A class-action lawsuit was filed against the corporate successors of the Fairmont Coal Company, seeking recognition and reparations for what the legal documents called “willful negligence compounded by racial discrimination resulting in mass casualty.” Miriam, Ruby’s granddaughter and the civil rights attorney who had dedicated her career to fighting injustice, flew to West Virginia for the press conference announcing the lawsuit. She brought the wooden canary from the photograph, the same one little Samuel Jr. had held in his small hands 108 years earlier.

It had been passed down through her family like a sacred relic from Ruby to her mother to Miriam herself, its full significance forgotten until Elena’s discovery restored its meaning. Now it would take its place in a new exhibit at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture alongside the other five canaries and the documents that proved what the company had tried to hide.

Isaiah’s name was added to the Manonga Memorial, not as a victim but as a hero. A bronze plaque was installed beside the granite obelisk telling the story of the Black carver who had tried to save his fellow workers when the company and the country refused to hear him. He gave them warnings carved in wood, the inscription read. “When the company silenced his voice because of the color of his skin, he gave them a chance to live.”

On December 6, 2023, the 116th anniversary of the Manonga mining disaster, a ceremony was held at the memorial unlike any in the town’s history. Descendants of the victims and survivors gathered from across the country—Black and white families standing together for the first time to honor their shared history. Labor historians, journalists, civil rights activists, and local residents filled the small cemetery, their breath forming clouds in the cold December air.

Elena Vasquez stood at the podium, the photograph that had started everything projected on a large screen behind her. Isaiah’s family was visible to all. “This photograph,” she said, her voice steady despite the emotion swelling in her chest, “looks innocent at first glance. A Black family standing before their modest home in a mining town. A father, a mother, two children. They look like so many other families from that era—hardworking, hopeful, determined to build a better life. But when you look closer, when you notice what the child is holding, you see something else entirely. You see evidence of courage in the face of indifference. You see proof that one man tried to save hundreds of lives and was dismissed because of the color of his skin.”

She paused, her eyes moving across the diverse crowd gathered before her. Miriam sat in the front row, the wooden canary resting in her lap, tears streaming down her weathered face. Beside her sat descendants of the seven survivors—Black and white families united by a shared debt to a man history had tried to erase. Behind them stood the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the 362 men who had died—families who finally knew the full truth of what had happened to their loved ones and why warnings had gone unheeded.

“Isaiah never received recognition in his lifetime,” Elena continued, her voice growing stronger. “He was called superstitious, a troublemaker, an unreliable source. He lost his job, his home, his community. He died in 1934 in a small apartment in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, still carrying the guilt of not having saved more lives, still wondering if anyone would ever believe him. But his wooden canary survived, his message survived, his truth survived. And today, we honor his memory—not just as a hero of labor history, but as a Black American whose voice deserved to be heard, whose warnings deserve to be heeded, whose courage deserves to be remembered.”

The ceremony concluded with the unveiling of a new sculpture—a life-sized bronze figure of Isaiah himself, holding a carved canary up toward the sky, his face lifted in eternal hope. At his feet, an inscription bore the words, “Bessie had written to her sister in 1912. They did not listen to my husband because of what he is. But the canaries knew; the canaries always knew, and someday the world will know, too.”

As the crowd dispersed into the gray December afternoon, Miriam approached Elena with tears still wet on her cheeks. She pressed the wooden canary into Elena’s hands—the same small bird that had traveled through four generations, carrying its secret message through a century of silence. “My great-grandfather’s courage was hidden for so long,” she whispered. “You gave it back to us. You gave him back to us. You gave his voice back to history.”

Elena looked down at the small carved bird, its wings folded, its beak open in frozen song, its feathers hiding a message that had waited 116 years to be heard and believed. In mining communities, canaries were warnings. They were the difference between life and death. For Black miners in Jim Crow America, they were sometimes the only witnesses whose testimony couldn’t be dismissed.

And sometimes, Elena thought, they were the difference between forgotten and remembered, between silenced and heard, between an innocent photograph and a story that changed how we understand our past and ourselves.

The story was complete, but its impact was just beginning.