The boots on the wooden porch stopped midstep.

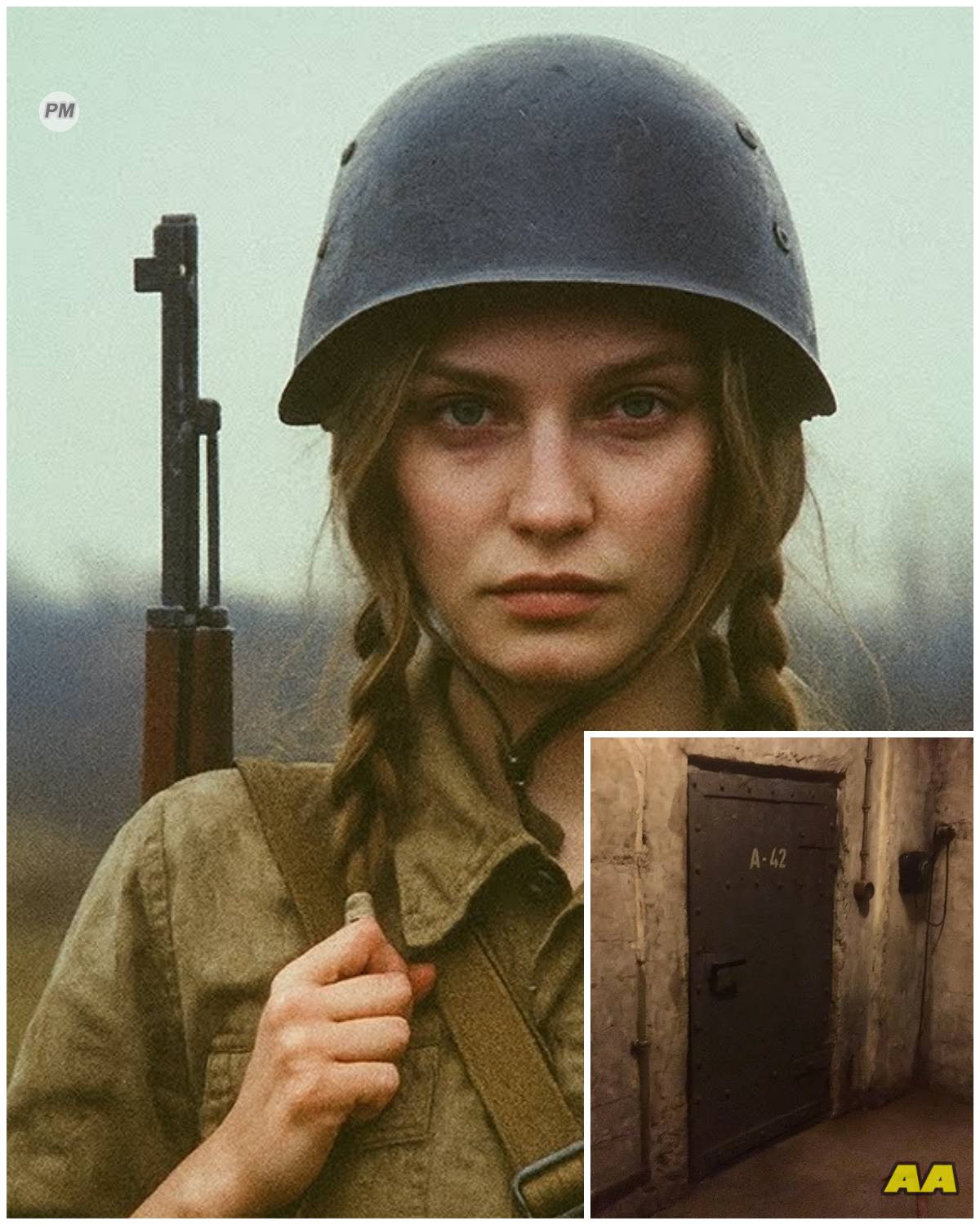

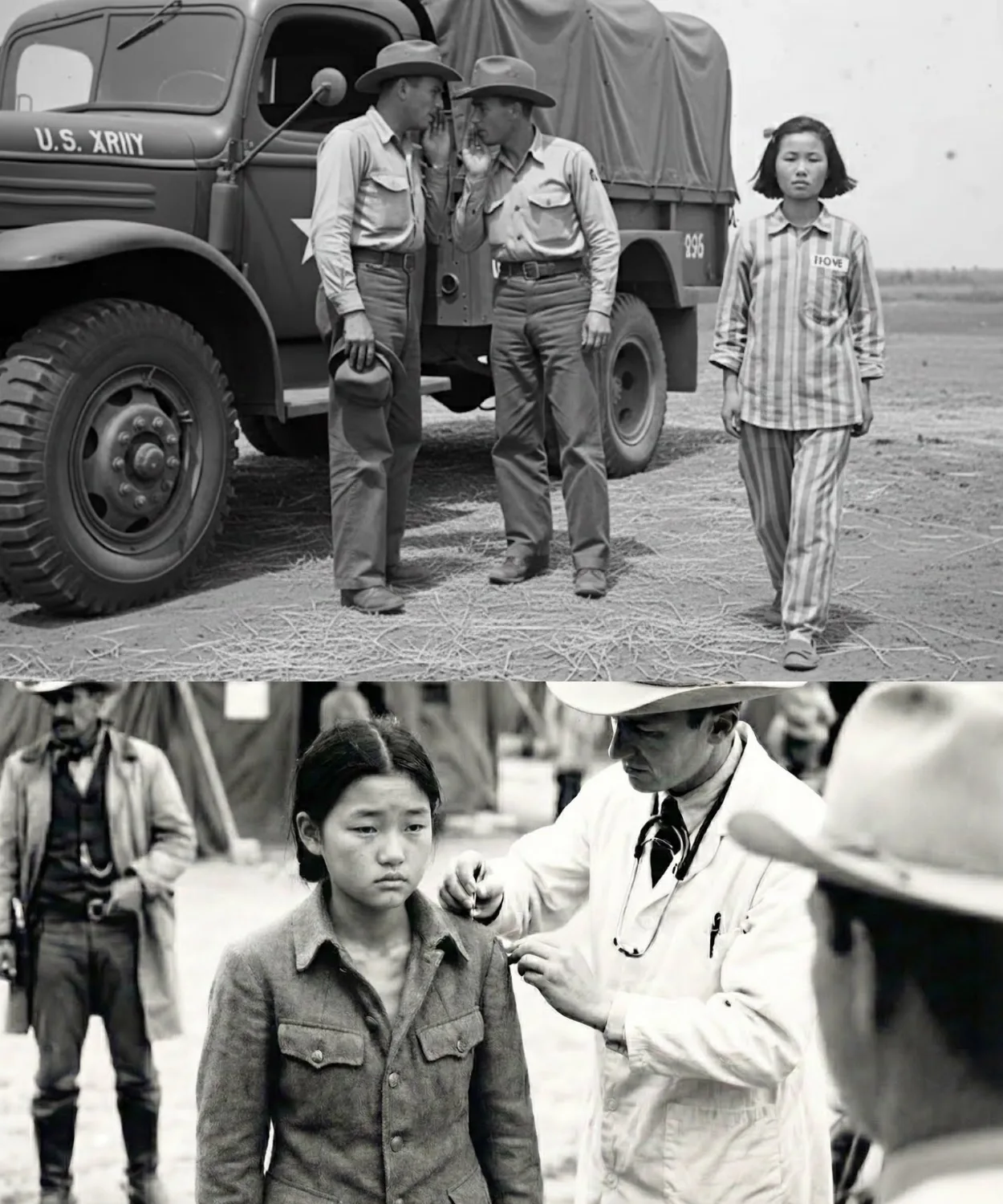

A 15-year-old girl, gaunt as a famine struck ghost, stepped off the army truck and into the dust of the Texas ranch.

Her uniform hung from her like rags on a coat hanger.

She weighed just 68 lb.

The wind blew straw across her shoes as a group of American cowboys turned part-time guards watched in frozen silence.

One took off his hat.

Another muttered, “She can’t be more than 12.” Inside the barn-turned clinic, a medic lifted her arm, his fingers wrapping fully around her wrist like he was handling a bird’s leg.

She didn’t flinch.

She didn’t blink.

She just stared ahead, blank, silent.

Her ribs looked like the slats of a shutter.

A cowboy turned away, swallowing hard.

Another whispered, “We were told they were monsters, but there were no monsters here.

Only a girl, half starved by war, stepping into a world she’d been told would devour her.

And now she was in their hands.

The truck door rattled open with a metallic clank, and the dust of the Texas plains rose in a slow curl around the boots of the guards.

Inside, a dozen girls sat in silence.

uniforms crumpled and faces hollowed by months of hunger and fear.

They didn’t move until ordered, and even then it was with the hesitancy of animals uncertain if the cage door had really opened.

The last to descend was the smallest of them all.

She stepped down barefoot.

Her shoes had been lost somewhere between Nagasaki and San Francisco, and her feet hit the hot dirt like they didn’t belong to her.

Her eyes scanned the horizon.

There was no barbed wire in sight.

Only cattle, horses, hay bales stacked like sleeping giants, and a handful of American ranchers with rifles slung over their shoulders like afterthoughts.

The sun was brutal.

The air smelled of sweat, leather, and manure.

For a moment, nothing moved.

The cowboys, rough-skinned men with rolled up sleeves and tobacco stained lips, just stood there watching the girls disembark like ghosts from a shipwreck.

The 15-year-old’s frame was skeletal, her cheeks sunken, her skin pulled tight over bone like rice paper stretched across bamboo.

One of the men let out a breath through his nose and whispered, “Not to anyone in particular.

Hell, she’s just a kid.” Another spat into the dirt and looked away.

Whatever they’d been told about enemy PWs, saboturs, spies, fanatics.

This wasn’t it.

This was something else entirely.

She didn’t blink as she was lined up.

Her face was unreadable, not with discipline, but with absence.

The eyes had receded, the mouth a tight line, the shoulders too thin to hold the idea of defiance.

When one of the ranchers stepped forward to call roll, she didn’t understand the words, but she recognized the rhythm of command.

Her hands twitched reflexively to her sides.

Stand straight.

Don’t speak.

Endure.

Her name was muttered by another Japanese woman who knew enough English to translate.

Her name is Kiomi,” she said.

The cowboy wrote it down on a clipboard with a puzzled frown, stumbling over the spelling.

“How do you say that again?” But Kiomi didn’t respond.

They brought her to a side barn where the medical officer had set up a makeshift infirmary.

just a cot, a scale, and a battered steel table with gauze, iodine, and a pair of reading glasses resting on an open log book.

The medic, a young man with sunburned ears and steady hands, motioned for her to sit.

Kiomi obeyed without sound.

He knelt beside her, carefully pushing back the torn sleeve of her uniform.

Her arm felt like it might snap.

He pressed a finger to her wrist to find a pulse.

It was slow.

Too slow.

He looked up, locking eyes with the cowboy standing just behind him.

She weighs maybe 68 lb, he muttered.

The cowboy swore under his breath and took off his hat.

That ain’t a soldier, he said.

That’s a scarecrow.

The medic ran his hand gently along her rib cage, counting without needing to say anything aloud.

Every rib was visible.

Her abdomen was caved in.

There were bruises, old ones, healed in strange shapes, and her legs trembled just sitting still.

He offered her a cup of water.

She didn’t move.

He brought it to her lips, and she drank it like she was tasting something forbidden.

Her face didn’t change, not even a twitch, just a mechanical swallowing.

“I’ve seen calves come out of the winter in better shape,” another cowboy said, softer than he meant to.

“They weren’t sure what disturbed them more, her silence or the fact that she didn’t look scared.

She looked used to this, used to being examined, weighed, prodded, ignored.” The cowboy with the clipboard cleared his throat and scribbled 15 beside her name, as if even that needed a question mark.

The barn creaked.

A horse shifted in the next stall.

Outside the sun dipped lower behind the distant hills, casting long shadows over the corral.

And inside that room, the air thickened with something none of them could name.

It wasn’t pity, not yet.

It was the first flicker of understanding that this girl, this tiny, brittle girl, was not what war propaganda had promised them.

She wasn’t dangerous.

She was broken.

And in the silence of that realization, something in the room shifted.

The medic wrapped a blanket around her shoulders.

It dwarfed her.

She didn’t resist.

He looked at the cowboy again.

the one still holding his hat like it was a flag lowered in mourning.

We’re not set up for this, he said quietly.

The cowboy just nodded.

We’ll have to be.

Before she ever saw a cowboy or the red dirt of Texas, Kiomi had learned to vanish, not with magic or movement, but with silence.

It was wartime Japan, and silence was survival.

Her home was a half- collapsed wooden house on the edge of Nagoya, where roofs were patched with tarps and windows covered in newspaper.

Her father had died on a transport ship 3 years into the war.

Her mother boiled weeds for supper.

Her older brother, Satoshi, joined the army, and when he left, he didn’t look back.

That was the last she saw of him.

When the bombs came, howling firebrite, she crawled into a trench behind a neighbor’s chicken coupe and watched the sky turn orange.

Afterward, the air always smelled like burnt paper.

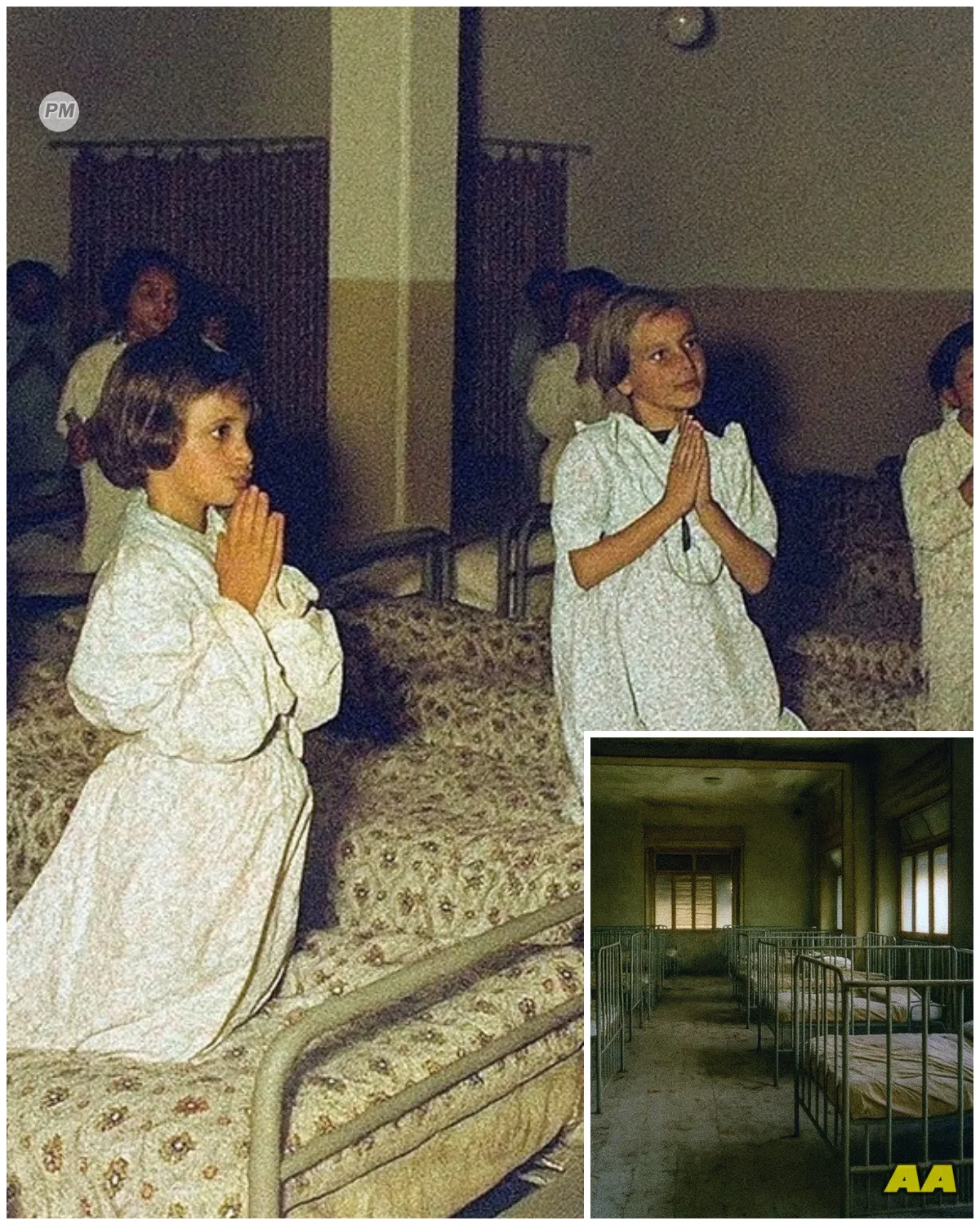

At 13, she was recruited as a tation tie, a volunteer assistant for the military.

The word sounded proud, honorable, but it meant scrubbing floors, folding blood soaked sheets, and carrying tin buckets of water too heavy for her bones.

In the corridors of the field hospital, she watched boys, no older than her brother, bleed out in silence.

The nurses, eyes hollow, whispered the same phrase to every girl who cried, “Endure for the emperor.” She said nothing.

She had stopped crying months earlier.

The military instructors handed out ration cubes and bushidto pamphlets in equal measure.

They taught them how to die with dignity.

They never taught them how to survive.

Surrender, they were told, was worse than death.

If the Americans captured them, they would not live to regret it.

The leaflets, American ones dropped from planes, said otherwise, but no one believed them.

The commanders burned those flyers without reading them.

“You will be used,” one officer warned, eyes flat.

“They will strip your honor, your clothes, your soul.

Better to bite your tongue off than be taken.” Kiomi nodded.

She meant it.

At the time, she believed every word.

She could still remember the image shown during drills.

A young woman on her knees, her captors behind her, her eyes blank with shame.

The message was clear.

To live meant dishonor.

But in August of that year, the skies changed.

The hospital fell silent.

The officers stopped shouting.

Then came the order, “Evacuate.” No fanfare, no explanation.

One of the nurses wept quietly in the corner.

Someone had heard it over a smuggled radio.

Japan had surrendered.

The empire was broken.

The emperor himself had spoken on the airwaves, something none of them thought possible.

His voice, thin and distant, said they must endure the unendurable.

No one moved.

For a moment, even time seemed to stop.

Kiomi folded her bloodstained apron, placed it on a cot, and walked out barefoot.

She was herded onto a truck the next morning with others like her, girls who had grown up in bomb craters, whose hands knew the weight of stretchers, but not the softness of beds.

They were silent on the road to the coast.

Some were crying, others stared straight ahead.

A few tried to run, but the guards did not shoot.

There was nowhere to go.

When they reached the harbor, American Marines stood waiting, not with whips, but with clipboards.

It confused everyone.

They were loaded onto a ship bound for America.

It was not a prison barge.

It had real bunks, food trays, soap.

Kiomi stayed below deck most of the time.

The sea made her sick.

The motion, the smell, the unnatural quiet of the hold.

All of it blurred into a waking dream.

She ate what she was given, but never finished her plate.

Not because she wasn’t hungry, but because finishing would make it real.

She watched the other girls sleep with their backs to the wall, still bracing for a blow that never came.

Each day passed in a kind of hush, the war receding behind them like smoke on the water.

One girl whispered that America was a land of glass towers and torture chambers.

Another said they fed their prisoners to animals.

Kiomi said nothing.

She only gripped the edge of her cot and stared at the ceiling, counting the bolts, waiting for the horror to begin, but it didn’t.

Days passed, then weeks.

The ship slowed, and finally it docked.

Not in a dungeon, but at a port where sunlight spilled across iron rails, and the guards squinted from under their hats like farmers on harvest day.

She stepped off the ramp onto American soil and smelled hay instead of gunpowder.

Horses winnied in the distance, and in the far off fields of Texas, someone was playing a banjo.

It made no sense.

None of it.

And still, she walked forward because there was nowhere else left to go.

The barn door creaked as it swung shut behind her, and Kiomi stood motionless for a moment, unsure whether to enter or retreat.

A guard? No, not a guard.

A cowboy gave her a nod and gestured toward a corner where a simple bed had been made.

It was no more than a stack of hay with a wool blanket folded neatly on top, but it was clean.

She walked toward it slowly, her feet unsure, every step uncertain.

Her eyes darted across the space.

A small stove flickered with orange flame casting moving shadows on the wooden walls.

A horseshoe hung above the door, and from the next stall over came the slow, even breath of a sleeping cow.

She lowered herself onto the hay, expecting it to scratch, to bite, but it didn’t.

It was soft, warm, even.

She clutched the blanket and pulled it around her shoulders like armor.

The fibers brushed against her skin, and she flinched.

Not because it hurt, but because it didn’t.

It was the first thing to touch her gently in months, maybe years.

She lay back, stared up at the rafters, and listened.

No boots stomping, no shouted orders, no sobbing, just the soft crackle of firewood and the muffled grunt of animals settling in for the night.

The smells were strange.

Dust, leather, smoke, not the familiar stench of disinfectant and rotting bandages, not the acrid breath of bombed out cities.

This was cleaner, earthier.

It confused her.

Her body was tense, rigid beneath the blanket, as if it would be snatched away at any moment.

She did not sleep.

She didn’t know how anymore.

Sometime in the night, the barn door creaked again.

She jolted upright.

A man entered.

A cowboy with a faded red bandana around his neck and a tin cup in his hand.

He didn’t approach quickly.

Instead, he crouched by the stove, stirred something in a pot, then ladled it into the cup.

Steam rose in curls.

He walked toward her slowly, not making eye contact, and held the cup out.

She didn’t move.

“Stew,” he said softly.

The word meant nothing to her, but the smell did.

She looked at it the way someone might look at a trap.

It was brown, greasy.

Chunks of vegetables bobbed alongside shreds of meat.

The scent punched through her guard like a bullet.

Onions, beef, broth, fat.

Her stomach clenched, not with nausea, but with a sudden wild hunger.

Still, she didn’t reach for it.

She’d been taught that food from the enemy meant poison, meant shame.

The man placed the cup on the floor beside her and backed away, nodding once before returning to the stove.

She watched the cup as though it might vanish.

Slowly, cautiously, she picked it up.

The metal was warm against her hands.

She brought it to her lips, pausing just before the broth touched her mouth.

Then she drank.

The heat hit her tongue like a flame.

salt, oil, something sweet, something bitter.

Her body jerked in surprise and she nearly dropped the cup.

But she didn’t.

She took another sip and another.

Her eyes stung, not from spice, but from something deeper, something old and buried.

She wasn’t just tasting food.

She was tasting memory of rice balls in summer, of her mother’s miso soup before rationing began, of the last time her stomach had known more than emptiness.

She wiped her mouth with the back of her hand.

The cowboy said nothing.

He only sat near the stove, whittling a piece of wood.

His presence was quiet, not threatening, not even curious, just there, as if she wasn’t an enemy, but a girl.

She didn’t know what to make of that.

Back home, being seen was a danger.

Being weak was a curse.

But here, in a barn that smelled of hay and soup, someone had handed her food and walked away.

Not to watch her, not to interrogate her, just to feed her.

and that more than the stew, more than the blanket, shook her to her core.

She set the empty cup down and curled under the blanket.

Her fingers clutched the edge, knuckles white.

Somewhere deep in her chest, something small shifted.

Not trust, not yet.

But the first fragile crack in the armor she’d been told to wear until death.

In the next stall, the cow exhaled a deep rumbling breath, and for the first time in a very long time, Kiomi closed her eyes.

When she woke, the blanket was still there.

That was the first surprise.

It hadn’t been taken in the night, hadn’t been replaced with something thinner, rougher, less hers.

She sat up slowly, her muscles aching from the unfamiliar stillness of real sleep, and pulled the wool tighter around her shoulders.

The fabric still held the warmth of her body, and in that moment the realization settled on her like morning frost.

This blanket was hers, not borrowed, not stolen, not temporary.

It had been given to her.

She clutched it like contraband, half expecting someone to yank it away and accuse her of theft.

But no one came.

No shouting, no punishment, just the sound of boots outside the barn and the far off braaying of animals.

On a small crate beside her bed sat a tin basin with a cloth and a bar of soap.

Folded next to it was a fresh pair of socks.

She stared at them as though they were sacred relics.

These were not just things.

They were symbols of care, of worth, of being seen.

Back home, she had learned not to expect anything permanent.

Her shoes had belonged to her brother first.

Her comb had cracked teeth.

Her ration card had her name misspelled, and no one ever bothered to fix it.

But here, every item, every small ordinary object carried with it the weight of something revolutionary.

A toothbrush, a cup, a comb with all its teeth.

They were unspoken declarations.

You are worth the effort.

That idea terrified her more than any weapon.

Later that morning, the barn door opened with a creek, and one of the ranch hands stepped in.

He was older than the others, with a limp in his left leg and a face that looked like it had been carved from sunbaked wood.

He didn’t speak much, just handed her a small burlap sack filled with feed and motioned toward the chicken coupe.

At first she didn’t understand.

She blinked, confused.

Surely this was a mistake.

She was the prisoner, the enemy.

Why would they trust her with anything alive? But he just smiled, half a smile, more in his eyes than his mouth, and pointed again.

She followed.

The coupe was warm and smelled of straw, feathers, and faintly eggs.

The chickens clucked as she entered, their heads twitching toward her with curiosity, not fear.

She knelt, opened the sack, and scattered the feed.

They rushed toward her in a feathered frenzy.

At first she flinched, but they didn’t peck.

They didn’t bite.

They simply ate, content in their routine.

She sat back on her heels and watched, the rhythm of it, strange but soothing.

It reminded her of the days before the firebombing when her mother kept two hens behind their home.

She remembered the sound of her mother’s voice calling them in the evening, and the way she’d gently tuck the eggs into her apron like treasure.

The memories hurt, but not like before.

This pain was duller, more like an echo.

The chickens pecked and strutted around her, unconcerned with wars or ideologies.

They didn’t care that she was Japanese or a girl or a prisoner.

They simply accepted her.

By the end of the week, the ranch hand showed her how to collect eggs, then how to clean the coupe.

The work was never forced.

He didn’t bark orders.

He just demonstrated, nodded, and left her to it.

She found that the silence of the coupe, punctuated only by clucks and the soft rustle of wings, was easier to bear than the silence of the barn.

It gave her hands something to do.

her mind a place to rest.

The cracks in her armor widened.

Back home, kindness was a strategy, a calculated show of loyalty to those above you.

Here it was quieter, unannounced, a bar of soap, a bowl of stew, a task that implied trust, and that trust began to unmake her.

That evening she sat on her haystack bed, clutching the blanket again, but this time not out of fear it would be taken, but because it had come to mean something.

It was not just a cover against the cold.

It was proof that she existed beyond utility, that someone thought she deserved to be warm.

She folded it over her legs carefully, almost reverently.

Then she reached for the comb, running it through her tangled hair with slow, deliberate strokes.

Each pull, each motion was like a quiet whisper to herself, “You are still here.

” And somewhere deep inside, the question stirred again, one she couldn’t yet say aloud.

“Why would the enemy treat me like this, if they were the monsters I was told they were?” That question still echoed in her mind as the night pressed in.

The barn quiet except for the shuffle of animals settling into their sleep.

But then something new broke the silence, faint at first, like a breeze dragging across a wire.

Then stronger, plucking, a banjo.

She sat up.

The notes bounced with a rhythm she couldn’t decipher.

too fast, too joyful, like a conversation between children who had never been bombed.

A harmonica joined in, whiny and bright.

Then came laughter, unrestrained, open from men who weren’t hiding in trenches or whispering under air raid sirens.

It wasn’t the laugh of madness or bitterness.

It was the kind she remembered from long ago when her brother used to chase her around the rice patties.

It hit her like a slap.

She pulled the blanket tighter and stared at the wooden slats of the barn.

The music didn’t stop.

The banjo strummed on, twanging something loose inside her chest.

She didn’t know the tune.

She couldn’t hum it back, but it stayed with her, an unwanted guest curling up beside her heart.

She hated it, and yet she didn’t want it to end.

The next morning, the scent hit her before her eyes opened.

It curled into the barn like a ghost, salty, greasy, thick.

Her stomach growled before her thoughts could catch up.

She sat up slowly and blinked.

One of the younger ranch hands stood in the doorway with a tray.

On it, eggs, bread, and two strips of something dark and sizzling.

Bacon,” he said, offering the plate like an apology.

She took it with both hands, fingers trembling.

The bacon glistened in the light, its edges curled like waves.

Back home, meat had become legend, spoken of, never seen.

Her mother once bought a single fish head from the black market and boiled it for two days to make broth.

The smell of this, of fat and fire, was overwhelming.

She stared at it, frozen.

The bread was warm.

The eggs jiggled slightly, but it was the bacon that stole her breath.

She raised it to her mouth and hesitated.

Her hands shook so badly she nearly dropped the tray.

Then she bit.

The crunch echoed in her skull.

Salt exploded on her tongue.

Grease slid across her lips.

Her throat tightened, not from disgust, but from memory.

starving neighbors, her mother’s hollow cheeks, a child crying in the next room because the rice was gone.

The bacon felt wrong.

Too much, too rich, too real.

Her eyes stung.

She gagged.

The ranch hand took a step forward, alarmed.

But she waved him off and forced herself to swallow.

Her body didn’t reject it.

Her mind did.

But then she took another bite.

Because hunger doesn’t ask for permission.

She ate in silence, chewing slowly.

Each bite an act of betrayal and survival at once.

The bread was soft, the eggs buttery.

The bacon still too much, but she finished it all.

She wiped her mouth with the cloth napkin, then folded it in half like she’d seen the others do.

She looked up.

The cowboy was gone.

Only the empty tray remained on the crate beside her.

Like an offering from a world that still didn’t make sense.

Outside the banjo started again, faint, playful.

She pressed the heel of her palm to her chest, trying to steady the beat of her heart.

The laughter came again, too.

Outside the barn, drifting in like pollen.

She hated that it made her wonder what they were laughing about.

hated that she wanted to know.

She had grown up in silence, in the shadow of whispers, warnings, and war drums.

Joy had always been distant, something rationed and rare.

Here it spilled out at random, uninvited, uncontrolled.

It felt dangerous.

It felt alive.

She didn’t laugh.

Not yet, but she did not cover her ears.

Later that week, while she was folding the washed eggshell colored cloths by the pump, a man in uniform approached her, not a cowboy this time, a sergeant.

His boots were polished, his expression unreadable behind the lines that seemed carved into his face like dried riverbeds.

In his hand, he held something small.

When he stopped in front of her, he didn’t speak right away, just extended the item.

It was a yellow pencil, short and dull at the tip, with a scrap of paper folded beneath it.

“Right home,” he said quietly.

Then he turned and walked away.

Kiomi stood there unmoving, the pencil in her fingers like it might combust.

Her mind reeled.

“Write home? Was this a test? A trap?” No one said this was allowed.

Back in Japan, the last letter she received from her mother was scribbled on a rice paper scrap delivered through military channels and censored into near nonsense.

Now she was being handed a chance to write back.

She stared at the paper like it was a map she couldn’t read.

Her thumb brushed the grain of the fibers, the soft edge of the pencil wood.

Her heart pounded with the rhythm of the question.

What could I possibly say? That she was alive.

That the Americans, the enemies, the devils, the monsters in propaganda posters had given her eggs and bacon, a toothbrush, a blanket.

Would her mother even believe it? The blank space in front of her felt like betrayal.

Every line she might write seemed like a confession.

I am here.

I am not dead.

I am not being tortured.

I am warm.

Every truth was a contradiction.

The idea of writing them down made her stomach not.

She sat on the crate outside the barn, pencil hovering above the page.

She wanted to write her mother’s name, but her hand wouldn’t move.

Not yet.

Back home, she’d been taught that silence was patriotism, that words were dangerous unless they served the emperor.

That communication could betray the state, the family, the self.

To write to her mother now would be to admit that her world had already crumbled, that her commanders were wrong, that surrender was not death, but something stranger, a life she didn’t understand.

She thought of the other girls on the ship, some younger, some older, how they kept their eyes low, their mouths closed.

What would they write if given the chance? Would they tell the truth? Would they even remember how? Kiomi lowered the pencil to the paper.

Her handwriting was stiff, clumsy, her fingers out of practice.

She began a sentence, then scratched it out, started another, stopped halfway.

The sun slipped lower in the sky, casting long orange shadows across the dirt.

The banjo again plucked something soft in the distance.

Her stomach tightened.

Then finally, she wrote two words.

I’m safe.

That was all.

No name, no address, no explanation.

Just two words.

Because that was the most radical truth she could offer.

She folded the paper, walked to the sergeant’s office, and placed it on the desk without a word.

He looked up, nodded once, and reached for the envelope.

As she stepped outside, something shifted.

The air smelled like sage and horses.

In the barn, the chickens were quiet.

She realized slowly, deeply, that she no longer expected the bomb sirens.

She hadn’t imagined a guard’s boot in over a week.

Her jaw, usually clenched in sleep, had begun to loosen.

The war for her was no longer in the present tense.

It was a memory, a shadow, still loud, still close, but behind her, and in its place, a whisper of something new.

Not trust, not forgiveness, but maybe the beginning of belief that this strange land with its pencils and pork and plucking strings was not hell.

It might not be home, but it was no longer the battlefield.

The next day, a different kind of summons came.

One of the older women, a nurse from Osaka, whispered the news as if it were sacred.

There would be a bath, hot water, real soap.

Kiomi’s first reaction wasn’t joy.

It was suspicion.

Was this a trick? Hot water was something spoken of in past tense.

Before the shortages, before the hospital had no heating, before the lice made even touching your own hair a kind of war.

She followed the others quietly to the far end of the barn where large galvanized tubs had been set up in a row, each one filled with water warmed over a wood stove.

The rising steam was hypnotic, curling in the cold morning air like incense.

A wooden crate held folded towels, cloths, and bars of thick yellow soap, coarse, square, and impossibly fragrant.

Kiomi reached for one and stopped, her fingers hovering over it like it might evaporate under her touch.

She picked it up.

It didn’t vanish.

The scent hit her first.

Lemon? No, something richer.

She couldn’t name it, but it made her dizzy.

She sat at the edge of the tub, dipped a cloth into the water, and watched the soap lather into a froth of white bubbles.

She hadn’t seen lather in years.

Not real lather, not the kind that promised to strip away not just grime, but memory.

One of the women sobbed quietly beside her, rubbing her arms over and over with the cloth as if she could erase the war from her skin.

Another closed her eyes as she dunked her hair beneath the water and emerged gasping, not from the heat, but from something deeper.

Resurrection.

That’s what it felt like.

Kiomi bathed slowly, carefully, each part of her body rediscovered beneath the suds.

She had forgotten what it meant to feel clean, not just not dirty, but clean.

Her own scent returned faint under the soap, familiar and startling.

She ran the cloth over the backs of her ears, her neck, her arms.

They were thinner than she remembered, but they were still hers.

When the last of the tubs had gone cool, they dried themselves and dressed again in their borrowed clothes.

The towels were stiff, the fabric strange, but no one complained.

For the first time, they looked at one another, not as shadows or statistics, but as women.

One borrowed a mirror from the messaul and passed it around.

They stared at themselves, not in vanity, in disbelief.

Someone had managed to sneak in a tin of red lipstick, smuggled, gifted.

No one knew.

It made its way down the line like contraband, passed from hand to hand.

Kiomi didn’t use it, but she held it.

That alone was enough, a color from a world she had forgotten.

Then came the sound of boots outside the barn.

cowboys.

Two of them leaning against the doorframe, peeking in, not learing, not laughing at, just curious.

One tipped his hat and said something in English too fast to understand.

The older women stiffened.

Komi tensed, but then he lifted a ridiculous oversized saloonstyle hat off his head, placed it on the other cowboys, and both of them burst into laughter.

The younger one stumbled backward, pretending to dance with an invisible partner tripping over his own boots.

The sound was honest, harmless.

It didn’t pierce like gunfire.

It filled the barn with something disarming.

Some of the women chuckled, quiet at first, then louder.

Not one of them had heard that sound in months.

The cowboys walked off, still laughing, never glancing back.

No threat, just two boys playing with time in a world no longer at war.

Kiomi stared at the leftover soap in her palm.

It was melting now, soft around the edges, but it hadn’t disappeared.

Neither had she.

That evening, a fire was lit just beyond the barn, its glow stretching long fingers across the dirt as dusk settled over the ranch.

The air cooled quickly, carrying with it the smell of smoke and dry grass.

Kiomi sat with the other girls in a loose circle, their blankets wrapped tight around their shoulders.

The fire crackled steady and alive, and for once no one was counting minutes or watching shadows.

The cowboys sat a short distance away, not crowding them, not guarding them, just sharing the same night.

One of the younger men shuffled a deck of cards, the worn edges whispering against each other.

He crouched near Kiomi and held up a card, speaking slowly.

“This is king.” He tapped the face, then handed it to her.

She stared at it, unsure, then nodded.

“Another card.

Queen.” She repeated the word softly, testing it.

The others watched, some smiling, some still cautious.

The game unfolded clumsily, rules explained through gestures and broken phrases, but it didn’t matter.

Winning wasn’t the point.

Sitting together was at some point someone produced a harmonica.

It was small, scratched, clearly loved.

The cowboy held it out to Kiomi without ceremony.

She hesitated.

Instruments back home were reserved for ceremonies, for controlled moments.

This felt informal, dangerous, but she took it.

Her fingers wrapped around the cool metal.

She brought it to her lips and blew.

The sound that came out was sharp and wrong.

The group burst into laughter, not mocking, just surprised.

She tried again.

Another sour note, more laughter, and then, without warning, she laughed, too.

It escaped her before she could stop it, light and startled, as if it didn’t belong to her.

The sound hung in the air for a moment, fragile and unreal.

She clapped a hand over her mouth, eyes wide.

The others stared, then one of the women laughed as well, then another.

The fire light danced across their faces as the sound grew, layering over itself, shaky at first, then stronger.

Kiomi’s chest tightened.

Guilt surged in fast and hot.

How could she laugh when her mother might still be hungry? When her brother was likely dead, when cities lay in ash across the ocean? The laugh caught in her throat and died away.

But the cowboys didn’t stop smiling.

They didn’t hush her.

No one told her to be quiet.

No one punished joy.

That was when the question rose.

Uninvited and unstoppable.

If the enemy valued her life enough to teach her a game, to hand her music, to laugh with her instead of at her, why had her own country treated her as disposable? The thought felt dangerous, treasonous, but it wouldn’t leave.

She looked around the circle.

These girls had been told the same thing she had, that they were tools, that suffering was proof of loyalty, that death was preferable to capture.

And yet here they sat, fed, warm, learning words in another language, laughing by a fire lit by men they had been trained to hate.

One of the older women spoke softly in Japanese, almost to herself.

They see us.

No one argued.

Kiomi met the eyes of the cowboy across the fire.

He didn’t look away.

There was no triumph in his gaze, no hunger, just recognition, as if he were seeing a person, not a uniform.

She lowered her eyes first, her heart pounding.

That simple exchange unsettled her more than any shouted command ever had.

The harmonica made its way back around the circle, this time producing something closer to a tune.

Someone clapped.

Someone else hummed.

The fire popped and shifted.

For a brief stretch of time, the war loosened its grip.

But the reckoning lingered.

If dignity could be offered so easily by strangers, what had been stolen from them by those who claimed to protect them? Kiomi pulled her blanket tighter and stared into the flames.

The fire didn’t judge.

It just burned.

She didn’t know the answer yet.

She only knew that once the question had been asked, it could never be unasked.

Are you finding this story as powerful as we do? If so, please like the video and drop a comment below telling us where in the world you’re watching from.

We’d love to hear your thoughts.

Thousands of miles away across the Pacific and deep within the gray corridors of a Tokyo military intelligence office, a clerk unfolded a letter.

The paper was thin, the ink smudged slightly, and it had passed through many hands.

It had been flagged, intercepted.

A letter written by a former field assistant, now a prisoner, allegedly, held in Texas of all places.

The note was brief, carefully chosen words in a girl’s handwriting.

It said little, but it said everything.

I’m safe.

That was all.

To the Americans, it had seemed like a simple message home.

To the Japanese authorities, it was a warning bell.

The letter had passed the sensors in the states, but not in the broken remains of the Japanese military chain of command, where paranoia still lingered like smoke.

That two-word sentence contradicted everything the empire had taught.

According to the official narrative, American camps were savage and merciless.

Surrender was not survival.

It was death of honor.

But here was a girl alive, safe, writing with her own hand.

The contents were quietly shared among intelligence officials.

Some scoffed, others frowned.

A few said nothing at all.

What disturbed the most wasn’t what the letter said.

It was what it didn’t say.

No complaints, no hunger, no cruelty, no broken bones, just safety, just survival.

The silence between the lines screamed louder than any accusation.

Back in Texas, Kiomi had no idea her letter had traveled so far or caused such ripples.

She had returned to her daily routines, gathering eggs, feeding chickens, sweeping hay.

But something inside her had shifted.

A small invisible revolution had taken place.

One morning while walking past the ranch house, she heard the slam of a screen door and turned to see a small girl, maybe eight or nine, bounding down the steps, her braid flying.

In her hand, she held a thin piece of fabric, pink, bright, alive, a ribbon.

She ran up to Kiomi without hesitation and held it out.

for you,” she said in English, grinning before skipping off toward the paddic.

Kiomi held the ribbon like it was gold.

She didn’t know what to do at first.

“Wear it? Keep it hidden? What did it mean to accept something that had once been unthinkable? That evening, she tied it into her hair, just above her ear, neat and small.

The reaction was immediate.

Some of the women gasped, a few turned away.

One whispered that it was shameful, but no one said it to her face.

They couldn’t because they had seen her change slowly, quietly, openly.

The ribbon was more than decoration.

It was defiance, not against Japan, but against what Japan had told her to be, against the idea that she was only a function, a servant to war, a body to be used and discarded.

She looked into the mirror briefly and saw not a soldier, not a burden, not a tool, but a girl.

That night she walked through the barn and passed a group of Americans playing cards.

One looked up and tipped his hat.

No comment, no mockery, just a glance of recognition.

She nodded back and kept walking because she wasn’t performing.

She wasn’t pretending.

She was becoming slowly, day by day, reclaiming her own shape with a pencil, with soap, with a ribbon, and somewhere in a government office across the sea.

Her quiet rebellion had already landed like a stone in still water.

They had read her letter in Tokyo, but they would never understand the weight behind those two small words.

Not unless they’d stood barefoot in a barn with warm food in their stomach and music in the air and realized for the first time they were allowed to live, to feel, to become, to be.

The notice came quietly, pinned to the board outside the messaul in plain English and careful Japanese, repatriation.

The word looked unreal, like it belonged to another life.

Kiomi stood before it with her hands folded, reading it again and again until the letters settled into meaning.

She would be going home, not back to the girl she had been, not back to the world that had burned and starved her, but back to a country changed beyond recognition.

And she would not be the same either.

On the morning of departure, the medic weighed her one last time.

He checked the scale twice, then smiled to himself.

102 lb.

He wrote it down neatly, as if recording a quiet victory.

When she had arrived, she had weighed 68.

The number itself had been a shock, a fact too stark to argue with.

Now the difference showed everywhere, in her cheeks, in the steadiness of her walk, in the way she met people’s eyes without flinching.

The war had not been kind to her body, but it had not taken everything.

She was issued a new coat, heavy and warm, the fabric smelling faintly of soap and storage.

A pair of glasses followed, fitted carefully by the medic after she admitted she had not seen clearly in years.

The world sharpened instantly.

Edges appeared where there had only been blur.

Faces became distinct.

She blinked hard, overwhelmed by the clarity.

“No one should have to live in a blur,” the medic said gently, repeating words he had used before.

She nodded, understanding more than the language aloud.

“In her small bundle, she packed the things that had become hers.

The diary filled with uneven handwriting, the ribbon now faded from sun and washing, the pencil worn almost to nothing, and folded carefully into the inside pocket of her coat, a letter.

It was short, written by one of the cowboys in awkward, careful words.

He wished her well.

He said he hoped she would remember Texas kindly.

He signed his name and added almost as an afterthought.

You’re tougher than you look.

She boarded the truck with the others as the sun crested the horizon.

The ranch stood quiet behind them, fences stretching out into the distance, cattle lowing softly, as if unaware that anything was ending.

The cowboys lined up near the gate.

No speeches, no salutes, just hats tipped low, one by one.

Kiomi paused, turned, and bowed her head once.

It was not submission.

It was acknowledgment.

Then she climbed into the truck and did not look back.

The ship that carried her home was larger than the one that had brought her across the ocean, but it felt different, lighter.

She stood on deck as the coastline faded, the wind tugging at her coat, and opened her diary.

She read entries she barely remembered writing.

Observations, confessions, questions.

One line stopped her breath.

I do not understand this war anymore.

She closed the book slowly.

She didn’t tear the page out.

She didn’t cross the sentence away.

It was true, and perhaps it always would be.

The voyage back was quieter than the first.

There was no dread coiled in her stomach, no waiting for cruelty to arrive.

Instead, there was a hollow space filled with thought.

What would Japan look like now? Would her mother still be alive? Would there be food? Would there be room for a girl who had been fed and sheltered by the enemy? She did not know, but she knew she would walk onto that shore standing upright.

When the ship finally docked, the port was scarred and subdued.

Buildings leaned like tired men.

Faces were thin.

The air carried the weight of loss.

As she stepped onto Japanese soil, she felt the ground steady beneath her feet.

She touched the ribbon in her hair, then the diary in her coat.

These things anchored her.

They reminded her that dignity was not something a nation could grant or take away.

She blended into the crowd, another survivor among many, carrying no banner, no answers, only memory.

She would never forget the ranch, the barn that was warm, the banjo strings in the night, the bacon she had gagged on and eaten anyway, the pencil, the soap, the laughter that had felt like rebellion.

She had arrived at the ranch weighing 68 lb, barely more than a shadow.

She left weighing 102, carrying something far heavier than flesh.

She carried the knowledge that even in war, humanity could survive.

If this story moved you, please like the video and tell us in the comments where you’re watching from.

And thank you for remembering a piece of history the world nearly forgot.