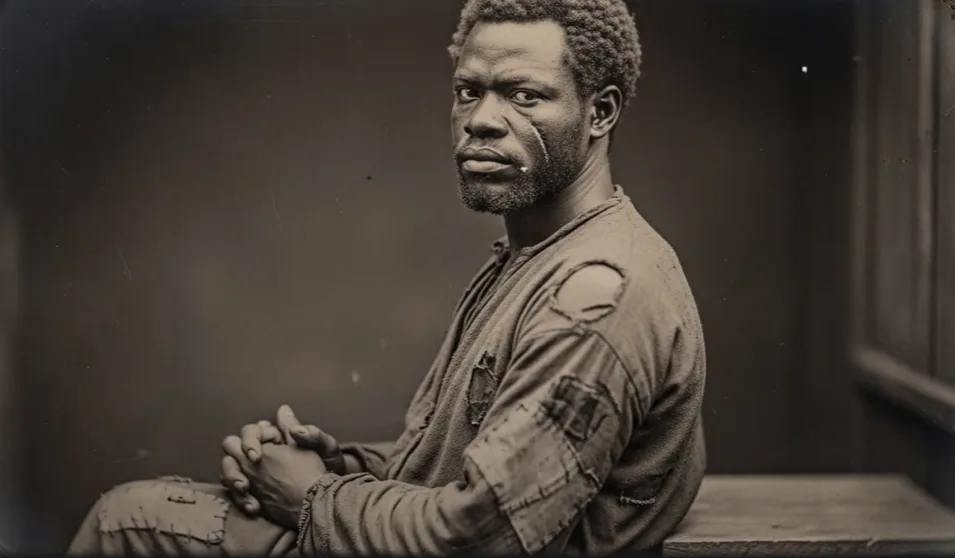

How One Enslaved Man’s Memory Changed the Future of Resistance: The Untold Story of Jabari Mansa

In 2019, a remarkable discovery was made in Bowford County, South Carolina.

Construction workers were demolishing an old plantation house when they stumbled upon a hidden document sealed in oil cloth, tucked away inside the wall.

The ink was faded but still legible, revealing a letter written in 1831 by a white overseer named Edmund Hail to his brother in Charleston.

What the letter contained was something that terrified Hail so deeply that he never sent it.

He had hidden it away, fearing the implications of its contents.

“There is a negro here,” Hail wrote, “who knows things he should not know.

He speaks of events before they happen.

The slaves believe he carries the spirits of his ancestors in his blood.

I have whipped him until my arm ached, and still he looks at me with eyes that see through time itself.

I fear this man, William.

I fear him more than any living thing.”

The negro’s name, according to plantation records cross-referenced with Hail’s letter, was listed as Jim in the ledger.

But that wasn’t his real name.

His real name was Jabari Mansa.

And what happened to him represents one of the most deliberately erased stories in American history.

Because Jabari didn’t just resist slavery through escape attempts or physical rebellion.

He resisted through something far more dangerous to the system that enslaved him.

He refused to let them take his mind.

What you’re about to hear has been buried for nearly two centuries.

The records were destroyed, the witnesses silenced, and the story itself was treated as too dangerous to preserve.

But fragments survived—court documents, auction receipts, letters like Hail’s that were hidden rather than destroyed, and testimony from enslaved people recorded decades after emancipation by researchers who understood that oral history carried truths that official records deliberately omitted.

When you piece these fragments together, they reveal something that plantation owners in the 1800s understood but could never admit publicly: that the most dangerous slave was not the one who ran or fought but the one who remembered.

Jabari Mansa arrived in Charleston Harbor in August 1807, one month before the act prohibiting the importation of slaves would officially end the legal Atlantic slave trade to the United States.

The ship was the Henrietta Marie, a Portuguese vessel that had operated under Spanish registry to circumvent increasing British naval patrols.

Records show that 312 Africans boarded that ship on the coast of present-day Senegal.

127 survived the crossing.

The rest were thrown overboard, their bodies feeding sharks that learned to follow slave ships across the Atlantic like vultures following an army.

But we’re not starting there.

We’re starting 37 years later, in 1844, with what happened in the woods outside Bowfort when Jabari did something that would be investigated by three separate court inquiries and ultimately lead to legislation specifically designed to prevent anyone from ever doing it again.

The incident involved twelve enslaved people from different plantations who met in secret on a Sunday night.

What they did during that meeting depends on who’s telling the story.

The white authorities claimed it was a voodoo ceremony designed to curse plantation owners.

The enslaved community said it was a teaching, that Jabari was passing on knowledge that needed to survive.

But everyone agreed on one detail after that night: two of the white men who discovered the gathering went slowly insane, speaking in languages they’d never learned, describing places they’d never seen, unable to distinguish their own memories from visions of events that hadn’t happened yet.

The courts called it hysteria; the enslaved people called it justice.

And Jabari Mansa, when questioned under torture about what he’d done, said only this: “I showed them what we remember.

And memory is a weapon they cannot take.”

To understand what he meant, you need to understand where Jabari came from and what he carried with him that proved more dangerous than any knife or gun.

The Wolof Empire in what is now Senegal maintained an oral tradition stretching back centuries.

They had griots—master storytellers who memorized the complete history of kingdoms, the genealogy of ruling families, and the wisdom accumulated across generations.

These men weren’t just entertainers.

They were living libraries, their minds containing information that would take years to transcribe if anyone had written it down.

But the Wolof deliberately kept this knowledge oral because written documents could be destroyed, stolen, or altered.

Human memory, trained and disciplined, proved more reliable than any archive.

Jabari’s grandfather had been a griot.

Not the highest rank, but respected enough that his family carried status.

They weren’t royalty, but they weren’t farmers or laborers either.

They existed in that middle tier of African society that white slave traders found most profitable—educated enough to be valuable but not powerful enough to be protected.

Jabari was 17 when the raiders came.

This wasn’t a random attack or village raid.

This was business.

The local chief, whose name history has conveniently forgotten, had signed a contract to provide 50 young men to a Portuguese trader named Valentim Da Silva.

The contract specified ages between 15 and 25, physically healthy, no visible diseases or disabilities.

Da Silva paid in textiles, rum, and iron bars, the standard currency of the slave trade, and the chief’s men selected their targets with the precision of people fulfilling a commercial order.

They took Jabari during the dry season when young men traveled to fishing villages near the coast to trade goods.

There were six of them, all from families with some education or skill.

The chief’s men didn’t capture random villages; they captured future leaders—people who would have become teachers, administrators, merchants, people whose knowledge and intelligence could be converted into labor value on American plantations.

The holding facility near the coast was a stone fortress the Portuguese had built specifically for processing human cargo.

It wasn’t a prison in the traditional sense.

It was a warehouse.

The captives were chained in large rooms, given minimal food and water, and kept alive just long enough to be transported to the ships waiting offshore.

During those three weeks in the fortress, Jabari watched as the psychological destruction began before the physical journey even started.

Some captives broke immediately, retreating into catatonic silence.

Others became violent, attacking the guards even though it meant immediate death.

But most did what Jabari did.

They observed.

They memorized details.

They tried to understand the system that had swallowed them so they might find some way to survive or exploit a weakness.

This wasn’t heroic; it was practical.

Warriors who didn’t study their enemies died quickly.

During those three weeks, Jabari met a man who changed his understanding of what resistance could mean.

The man was older, perhaps 40, and had been a griot of much higher rank than Jabari’s grandfather.

His name was Bubakar, and he’d been captured, deliberately taken because a rival political faction had sold him to Portuguese traders to eliminate his influence.

Bubakar understood something that Jabari at 17 hadn’t fully grasped yet.

They weren’t just stealing people’s bodies; they were attempting to erase cultures, languages, entire civilizations worth of accumulated knowledge.

“Listen to me carefully,” Bubakar said during one of the few moments when the guards weren’t watching.

“They will try to make you forget your name.

They will try to take your language.

They will beat you until you believe you are what they call you.

But if you can keep your memories intact, if you can preserve what you know about who you were before they took you, you carry something they cannot destroy.

Memory is not weakness.

Memory is the only weapon that survives every torture.”

This wasn’t a speech about hope or eventual freedom.

Bubakar was too practical for that.

He was teaching a specific survival technique, the preservation of identity through deliberate memory work.

The way a griot memorizes thousands of lines of genealogy, Jabari would need to memorize everything about himself that the slave system would try to erase.

His family’s lineage, the geography of his homeland, the stories his grandfather had told him, the taste of foods he’d eaten, the sound of his mother’s voice, the specific way sunlight looked at dawn over the Senegal River.

“They will take your freedom,” Bubakar continued.

“They will take your body, but your mind remains your own until you surrender it.

And if enough of us refuse to surrender, if we keep remembering and teaching what we remember, they cannot fully win.

They can enslave us, but they cannot erase us.”

Three days later, Bubakar died.

The official cause was listed as dysentery, but the other captives knew better.

He’d simply stopped fighting to survive, his body giving up even though his mind remained clear until the end.

Before he died, he made Jabari promise something specific.

“Remember everything, not just your own story, but mine.

My name was Bubakar Dio, son of Madu Dio, griot of the Wolof court.

I was born in 1767 during the reign of…” and he recited his complete lineage going back seven generations.

Jabari memorized every word.

When the Henrietta Marie departed the African coast with its cargo of 312 captives, Jabari carried something in his mind that the ship’s captain, Antonio Fernandez, would never know existed.

He carried complete genealogical records of two Wolof families, oral histories of Senegalese kingdoms, and the systematic knowledge of how to preserve memory under conditions designed to destroy it.

This knowledge would prove far more dangerous to American slavery than any weapon.

The Middle Passage was exactly what you’ve read about in every account of the slave trade: systematic horror designed to maximize the number of surviving bodies while minimizing the cost of transport.

Jabari was chained in the cargo hold for 11 weeks.

His movement so restricted that muscles atrophied.

The ship’s surgeon, a man named Dr. Henrik Costa, kept detailed logs of the crossing.

These logs survived and were later acquired by abolitionist researchers.

They make for disturbing reading, not because of any explicit description of violence, but because of their clinical detachment.

Day 23. Five negroes died overnight, likely from dysentery, threw bodies overboard at dawn.

Day 30. Storm damage to forward cargo hold. Water contamination affecting approximately 40 negroes. Expect mortality increase.

Day 47. Fever spreading in a hold separated sick negroes to prevent wider contagion. 12 died.

Day 66. Food stores adequate. Water stores low but sufficient for estimated arrival date.

What these logs don’t record is what happened in the minds of the people chained in that darkness.

The psychological destruction that comes from sustained sensory deprivation, the smell of death and waste, the sounds of people losing their sanity, the knowledge that you’re being transported to something worse than this hell.

But Jabari had Bubakar’s teaching.

During those 11 weeks, while his body weakened nearly to death, his mind engaged in an act of defiant preservation.

He recited everything he’d memorized, every name in his family lineage, every story his grandfather had told him, every geographical detail of his homeland.

When he finished his own memories, he recited Bubakar’s lineage, the one he’d memorized before the old griot died.

When he finished that, he began memorizing new things.

The faces of people chained near him, the patterns of the ship’s daily routines, the specific phrases the Portuguese crew used when bringing food or inspecting cargo.

This wasn’t optimism.

It was technique.

He was deliberately exercising his mind the way an athlete exercises muscles, keeping it functional despite conditions designed to destroy cognition.

Other captives noticed what Jabari was doing.

A woman chained near him, whose name he would later learn was Aminata, asked him why he was whispering constantly.

When he explained, she understood immediately.

She’d been a merchant’s daughter, educated in calculation and recordkeeping.

She began her own memory work, reciting prices and trade routes and customer names from her father’s business.

Then she taught these to Jabari, and he taught her his genealogies without discussing it explicitly.

They were creating a small resistance network of shared memory, ensuring that if one of them died, the other would carry both sets of knowledge forward.

When the Henrietta Marie reached Charleston Harbor in August 1807, 127 captives had survived.

Jabari was so physically weakened that the ship’s surgeon initially categorized him as possibly unsuitable for sale.

But after three days of increased rations and forced exercise on the ship’s deck, Jabari recovered enough functionality to be moved to the auction block.

The slave traders had learned that buyers wanted to inspect merchandise carefully, so there was always a recovery period between arrival and sale, time for the cargo to regain enough strength to be presented as viable labor.

The auction happened at Ryan’s Mart on Charmer’s Street in Charleston.

The building still stands, now a museum, but in 1807 it was one of the busiest slave markets on the Atlantic coast.

The procedure was efficient and thoroughly documented.

Each captive was assigned a lot number, examined by potential buyers, and sold to the highest bidder.

The examinations were dehumanizing in ways that historical accounts often sanitize.

White men inspected teeth, felt muscles, examined genitals, looking for any sign of disease or defect that might reduce value.

Jabari was purchased by a rice plantation owner named Marcus Whitfield for $720, which was slightly above average price for a young male field slave.

Whitfield owned a large plantation on the coast near Bowurt, where rice cultivation required extensive labor in conditions that killed enslaved people at horrifying rates.

The flooded rice fields bred malaria and yellow fever.

The work was physically devastating, and the isolation of these coastal plantations meant overseers faced less scrutiny than on properties near towns.

The plantation records still exist, housed in the South Carolina Historical Society.

They show Jabari’s arrival, listed as “Negro Jim,” purchased in Charleston, August 1, 1807, assigned to fieldwork, no known skills.

That entry represents everything wrong with how slavery attempted to document human beings.

Jabari arrived with 17 years of education in oral tradition, the equivalent of a university-level training in his grandfather’s field.

He spoke three languages.

He could recite historical chronicles that would fill volumes if transcribed.

But to Marcus Whitfield, he was just “Negro Jim.” No known skills.

What happened next?

The way Jabari began his specific form of resistance started not with a dramatic action but with a quiet choice during his first week on the Whitfield plantation.

The overseer, a man named Thomas Brennan, was explaining work assignments through a combination of demonstration and violence.

He didn’t speak any African languages, and none of the newly arrived Africans spoke English.

So he communicated through beating anyone who failed to immediately understand what was required.

On the third day, Brennan was demonstrating how to plant rice seedlings in the flooded fields.

He showed the motion once, then shoved an African captive into the water and beat him with a wooden rod until the man attempted to replicate the action.

When it was Jabari’s turn, he performed the motion perfectly on the first try, having observed carefully what Brennan wanted.

This should have satisfied the overseer.

Instead, it unsettled him.

The look in Jabari’s eyes suggested understanding that went beyond simple imitation.

It suggested intelligence actively learning, not a beast being trained through repetition.

“You watching me, boy?” Brennan said, though Jabari couldn’t understand the English words yet.

“You think you’re smart?”

Jabari maintained eye contact, which was itself an act of defiance.

Enslaved people were supposed to lower their eyes when white men addressed them.

But Jabari had been taught by his grandfather that a man who lowers his eyes has already surrendered his dignity.

So he looked directly at Brennan, his expression neutral, giving away nothing but refusing to perform the submission that was expected.

Brennan struck him across the face.

Jabari didn’t flinch or cry out.

He simply continued to maintain eye contact.

Brennan struck him again harder.

Jabari’s expression didn’t change.

This confrontation continued for perhaps 30 seconds before Brennan realized he was losing something more important than physical dominance.

The other enslaved people were watching.

If he continued beating a man who refused to show pain or submission, he would demonstrate that violence had limits, that some things couldn’t be beaten out of people.

So Brennan made a strategic retreat, ordering Jabari back to work and making a mental note that this particular African needed special watching.

That evening, Brennan wrote in his daily log, “New negro from Charleston auction shows defiant character. Recommend strict discipline to prevent influence on other slaves.”

This entry would be the first of dozens documenting the overseer’s growing fear of a man who worked as required but somehow maintained an inner world that no amount of violence could reach.

That night, chained in the slave quarters, Jabari began teaching.

He spoke softly in Wolof to the other African-born captives nearby.

Not all of them understood his language, but several did.

And to those who understood, he explained what Bubakar had taught him.

They would try to take everything—your name, your language, your sense of who you were before they captured you.

But memory was territory they couldn’t fully occupy.

If you deliberately remembered and taught what you remembered to others, you created spaces of resistance that existed entirely in the mind.

“My name is Jabari Mansa,” he said, “son of Wame Mansa, grandson of Fod Mansa, who was a griot of the Wolof people.

I was born in…” and he recited his complete lineage the same way he’d been practicing during the Middle Passage.

Then he recited Bubakar’s lineage.

Then he asked each person there to tell him their real names, where they came from, and anything they remembered about their families.

And he memorized every word.

This was how it started.

Not with an escape attempt or a violent rebellion, but with the systematic preservation of identity through shared memory.

Within two weeks, there were 15 people on the Whitfield plantation engaged in this practice.

They would work in the rice fields during the day, performing the brutal labor required.

But at night they recited their histories to each other, creating a collective archive of African identity that existed only in their minds.

Marcus Whitfield had no idea this was happening.

Neither did Brennan.

They saw slaves who obeyed commands and performed their work.

They didn’t see the nightly gatherings where people spoke in African languages, preserving knowledge that the plantation system assumed would die with the first generation of African-born captives.

They didn’t understand that resistance could take forms that looked nothing like rebellion.

And they definitely didn’t anticipate what would happen when Jabari started teaching the children.

The Whitfield plantation had approximately 80 enslaved people, including children born there to African mothers and American-born fathers.

These children grew up speaking English as their primary language, Christianity as their only religion, and plantation life as the only reality they knew.

From the white perspective, second-generation slaves were ideal.

They had no direct memory of Africa, no alternative cultural framework, and could be shaped entirely by the plantation system.

But Jabari recognized these children as the actual battlefield.

If African culture could be preserved and transmitted to American-born children, the system’s ability to erase African identity across generations would fail.

So he began a patient, systematic campaign of education that would take years to show results and decades to reach its full dangerous potential.

I need you to understand something before we continue with what happened next.

Make sure you like this video and share it with someone who needs to hear this story.

Drop a comment telling me where you’re watching from and subscribe because what happens next in Jabari’s story is darker than anything we’ve covered so far.

The education happened in fragments, never in ways that white overseers would recognize as teaching.

Jabari would be working in the rice fields next to a 10-year-old child born on the plantation.

And he would say seemingly to himself, but loud enough for the child to hear, “In my homeland, we called this plant something different.

We called it Malo.”

And the way we prepared it for eating was…” and he would describe in careful detail West African cooking methods while appearing to simply talk to himself during work.

Or he would be walking past the children’s quarters in the evening and pause to tell a story, framing it as entertainment.

“Let me tell you about a warrior named Sundiata,” he would say, and then recite the epic of the Mali Empire’s founder, a story his grandfather had taught him.

To white observers, if they noticed at all, it looked like an old African telling fairy tales.

To the children listening, it was something far more powerful—evidence that there was a world and a history beyond the plantation, that their ancestors had been something other than slaves.

The plantation system had a fatal flaw built into its foundation.

It required treating enslaved people as property rather than human beings, which meant white owners rarely paid attention to the complex social and cultural lives that enslaved communities developed in their private spaces.

As long as work got done and no obvious rebellion occurred, overseers didn’t concern themselves with what slaves talked about among themselves.

This blindness created spaces for resistance that the system’s architects never anticipated.

Within five years of Jabari’s arrival at the Whitfield plantation, something remarkable had happened.

Approximately 30 people, including 15 children, could recite substantial portions of West African oral history.

They knew the genealogies of multiple families.

They could speak basic phrases in Wolof, Mandinka, and Fulani languages that most of them had never heard before.

Jabari’s teaching.

And most dangerous of all, they understood that their enslaved status was not a natural condition but a crime committed against them by people who had no moral right to their labor.

This last point was what truly terrified white plantation owners when they eventually discovered what was happening.

The system relied on enslaved people internalizing their inferior status, believing on some level that their enslavement was divinely ordained or naturally justified.

Education that explicitly taught otherwise was more dangerous than any weapon because it undermined the psychological foundation that made mass enslavement possible with relatively minimal physical force.

Marcus Whitfield didn’t notice the change at first, but Thomas Brennan, who spent every day directly supervising fieldwork, began to sense something shifting in the plantation’s social dynamics.

The slaves were performing their work adequately, but there was a quality to their obedience that felt different—less defeated, more like people choosing to cooperate temporarily rather than people who’d accepted their permanent status.

He couldn’t articulate this observation clearly enough to report it to Whitfield.

It was more intuition than evidence, but it made him nervous.

In 1812, five years after Jabari’s arrival, Brennan finally identified what was disturbing him.

He overheard a conversation between two children born on the plantation, maybe 8 and 10 years old, speaking in a language that definitely wasn’t English.

When he confronted them, asking where they’d learned an African language, the children claimed they didn’t know what he meant.

But Brennan wasn’t stupid.

He understood immediately that someone was teaching, and he had a strong suspicion who that someone was.

The African he’d noted as defiant during the first week, the one who maintained eye contact, who showed no fear during beatings, who worked competently but somehow never seemed broken—that African had been conducting a five-year campaign of cultural preservation right under the plantation’s nose.

Brennan brought this observation to Whitfield, who initially dismissed it as paranoid fantasy, but Brennan insisted on a test.

He brought several of the children to the main house and had them questioned separately about where they’d learned African words.

The children, with the survival instincts that enslaved people developed from birth, lied skillfully.

They claimed they’d heard their mothers singing songs in African languages they didn’t understand, that they were just repeating sounds without meaning, that they had no idea what the words meant.

This defense was plausible enough that Whitfield couldn’t conclusively prove deliberate teaching was occurring, but it raised his suspicions sufficiently that he ordered increased surveillance of Jabari specifically.

For the next two months, Brennan watched Jabari constantly.

He assigned him to isolated work details to separate him from other slaves.

He moved his sleeping quarters to a different building.

He implemented rules prohibiting conversation during work hours.

None of it made a difference.

The teaching had already taken root.

Thirty people had memorized what Jabari taught them, and they continued teaching each other even when Jabari couldn’t directly participate.

The network had become self-sustaining.

This was Jabari’s real genius as a resistance organizer.

He hadn’t created a system that depended on his personal leadership.

He taught a method that others could practice independently.

Every person who learned his memory techniques became a teacher capable of preserving and transmitting knowledge.

The plantation system could beat Jabari to death, and the resistance would continue because it existed in dozens of minds rather than one.

In 1814, Marcus Whitfield sold Jabari to a slave trader named Harrison Webb.

The sale wasn’t punishment for any specific offense.

Whitfield simply wanted this particular African off his property.

He’d become convinced, without being able to prove it, that Jabari’s presence was somehow contaminating the other slaves, making them less manageable.

Better to sell him at a small loss than risk whatever influence he was exerting.

The sale separated Jabari from the community he’d spent seven years building.

This was one of slavery’s most effective weapons—the constant threat of family separation and forced relocation that prevented long-term organizing.

But Jabari had anticipated this possibility.

Before the sale happened, he’d spent months preparing the others for his absence.

“Memory doesn’t require my presence,” he told them.

“Everything I’ve taught you lives in your minds now.

Teach your children.

Teach anyone who will listen.

And if we never see each other again, we’re still connected through the knowledge we share.”

Harrison Webb operated what was called a slave coffle, a mobile prison that transported enslaved people from coastal areas to inland plantations where demand and prices were higher.

Webb’s business model was simple and brutal.

Purchase slaves in Charleston or Savannah, chain them together in a line, and march them several hundred miles to markets in Georgia, Alabama, or Mississippi.

The journey typically took six to eight weeks and killed approximately 10% of the merchandise through disease, injury, or exhaustion.

Jabari was chained in a coffle with 43 other enslaved people.

Most of them were recently arrived Africans who spoke no English and had no understanding of where they were being taken or why.

The march began in Charleston and headed west toward Alabama, following routes that deliberately avoided major towns where abolitionists might try to interfere.

Webb’s method was to move the coffle primarily at night, rest during the day in isolated camps, and keep everyone chained except during brief exercise periods.

During this two-month journey, Jabari conducted what might be the most remarkable act of his resistance campaign.

He systematically memorized the story of every person in that coffle—43 people’s names, origins, families, skills, and memories.

He created a mental archive of 43 African identities that the slave system intended to erase.

And he began teaching them his memory preservation techniques during the evening rest periods when Webb allowed minimal conversation.

Most of these people would die on Alabama cotton plantations within a decade.

Their bodies would be worked to death and buried in unmarked graves.

Their names would be forgotten.

Their families would never know what happened to them.

And history would record them as nothing but inventory losses in plantation ledgers.

But for two months in 1814, they had someone who listened to their stories and remembered, someone who treated them as complete human beings with histories worth preserving.

And many of them learned enough of Jabari’s techniques to carry that practice forward, creating small networks of resistance on whatever plantations they ended up.

The coffle reached Montgomery, Alabama in October 1814.

Webb sold most of his merchandise at an auction there, but Jabari and seven others were transported an additional 100 miles to a cotton plantation owned by a man named Samuel Crawford.

Crawford’s plantation was large, even by Alabama standards.

Nearly 3,000 acres worked by over 200 enslaved people.

The scale was staggering.

This wasn’t a farm.

It was an industrial operation that processed human beings into cotton with mechanical efficiency.

The conditions on Crawford’s plantation were noticeably worse than what Jabari had experienced at Whitfield’s rice operation.

Cotton cultivation required year-round labor.

During planting season, enslaved people worked 16-hour days preparing fields and planting seeds.

During growing season, they maintained fields through constant weeding and pest control.

During harvest, they picked cotton from dawn until they literally collapsed from exhaustion with daily quotas that increased every year as overseers developed more efficient exploitation techniques.

And during processing season, they jinned and baled cotton in conditions that permanently damaged lungs from cotton fiber inhalation.

The plantation’s overseer was a man named Jacob Reeves, and he ran the operation with a level of systematic violence that made Thomas Brennan look gentle by comparison.

Reeves had developed a theory that maximum productivity came from keeping slaves in a constant state of fear, just below the threshold of rebellion.

He maintained detailed records of every enslaved person’s output, punished anyone who failed to meet quotas, and conducted random beatings to ensure that even high performers never felt safe.

His journals, which somehow survived and are now housed at Orburn University’s archives, make for genuinely disturbing reading—pages and pages of calculated cruelty documented with the same attention to detail that a scientist might give to an experiment.

Jabari’s arrival at Crawford’s plantation happened to coincide with an incident that would establish his reputation among the enslaved community there.

During his first week, a young woman named Sarah collapsed in the cotton fields from heat exhaustion.

Reeves’s response was to have her dragged to the side of the field and beaten for malingering, a standard punishment designed to discourage other slaves from attempting to avoid work through fake illness.

Jabari, who was working nearby and had witnessed Sarah’s collapse, said something that none of the other slaves had ever heard an African say to a white overseer.

“She needs water and shade.

She will die otherwise.”

Reeves turned to Jabari with an expression of genuine shock.

New slaves, especially African-born ones who barely spoke English, did not offer medical assessments or instructions to white men.

The social order required absolute deference.

By speaking at all without permission, Jabari had committed an offense that would normally earn severe punishment.

“What did you say, boy?” Jabari repeated himself, this time in clearer English that showed seven years of language learning.

“The woman needs water and shade.

What you call heat exhaustion will kill her within an hour if not treated.

I have seen this before.”

The purely economic argument convinced Reeves.

He ordered water brought and had Sarah moved to shade.

She survived, and that evening, Jabari had established something that would prove crucial to his continued survival and influence.

He demonstrated specialized knowledge that had commercial value to the plantation system.

Slaves who possessed useful skills received marginally better treatment because killing them meant losing their expertise.

Over the next several months, Jabari carefully cultivated a reputation as someone who understood health and could predict when slaves were actually sick versus malingering.

He couldn’t save everyone.

The work regime was designed to kill people regardless of medical care.

But he saved enough lives that Crawford and Reeves began consulting him regularly, pulling him out of fieldwork to examine sick slaves and advise on treatment.

This role gave Jabari something invaluable: access to nearly every enslaved person on the plantation and time to talk with them privately.

The conversations happened during medical consultations.

Jabari would be examining someone for malaria symptoms or treating an infected wound.

And while he worked, he would speak quietly, “What is your name?

Your real name, not what they call you.

Where were you born?

Do you remember your mother’s name?”

And he would memorize everything they told him, adding it to the mental archive he’d been building since 1807.

But he did something more than just collect information.

He taught the same memory preservation techniques he’d developed at Whitfield’s plantation.

“The stories you remember, teach them to your children,” he would say.

“The names of your ancestors.

Speak them aloud when you’re alone so you don’t forget.

They are trying to erase who we were before they took us.

Don’t let them succeed.”

By 1820, Jabari had been on Crawford’s plantation for six years and had created another network of cultural preservation involving at least 50 people.

They met in small groups during Sunday rest periods, ostensibly for Christian worship services, but actually conducting what amounted to classes in African history, language, and identity preservation.

The cover was nearly perfect.

White plantation owners actively encouraged slave Christianity, believing it made people more docile.

They never considered that enslaved people might use religious gatherings to maintain precisely the kind of cultural knowledge that Christianity was supposed to replace.

But Samuel Crawford was more observant than Marcus Whitfield had been.

In 1821, he noticed something that troubled him deeply.

The older African-born slaves on his plantation seemed to be teaching something to the younger American-born slaves.

He couldn’t quite identify what was being taught, but he noticed that children who’d grown up speaking only English were suddenly using African words.

That enslaved people who should have been thoroughly broken by the system showed signs of not exactly rebellion, but something more subtle—pride maybe, or just the absence of the complete psychological defeat that efficient plantation management required.

Crawford didn’t connect this observation directly to Jabari.

The plantation had over 200 enslaved people, and tracking the influence patterns of any single individual was nearly impossible.

But he did recognize that something needed to change.

So in 1822, he implemented a new rule.

No gatherings of more than five slaves outside of supervised work details, no private conversations during Sunday services, and random inspections of slave quarters to ensure nothing forbidden was being kept or taught.

These measures slowed Jabari’s teaching but didn’t stop it.

The network simply adapted, meeting in smaller groups, teaching more carefully, developing coded language for discussing African history that sounded like Christian theology to white observers.

The Kingdom of Our Fathers meant West African empires.

The crossing meant the Middle Passage.

The time before captivity meant pre-slavery African life.

White overseers heard what they expected—slaves discussing biblical kingdoms and spiritual journeys while completely missing that actual history and geography were being preserved.

In 1825, something happened that would eventually lead to the incident in 1844 that we started with.

A Methodist minister named Reverend Thomas Witmore began conducting missionary work among enslaved people on plantations throughout the region.

Witmore was a complicated figure.

He genuinely believed slavery was divinely ordained, but also believed that enslaved people had souls that required Christian salvation.

So he traveled from plantation to plantation, conducting services, teaching Bible verses, and trying to ensure that slaves received proper religious instruction.

Witmore’s visits to Crawford’s plantation created an opportunity that Jabari immediately recognized.

Here was a white man who actively wanted to teach enslaved people to read, specifically to read the Bible.

Witmore conducted literacy classes for any slaves their owners would permit to attend, believing that direct access to scripture was essential for genuine conversion.

Samuel Crawford, who was himself a devout Methodist, allowed approximately 20 slaves to participate in these classes, including Jabari.

This decision would prove to be one of the most catastrophically wrong judgments Crawford ever made.

Jabari learned to read with the focus of someone who understood this skill’s revolutionary potential.

The plantation system deliberately kept enslaved people illiterate because literacy enabled forgery of traveling passes, access to abolitionist literature, and the ability to learn about slave rebellions in other states.

A slave who could read was a slave who could educate himself about the world beyond the plantation and potentially organize others more effectively.

Reverend Witmore, like most white missionaries, never considered that teaching slaves to read might have consequences beyond religious education.

He assumed that enslaved people who could read would naturally accept the biblical passages that appeared to justify slavery—the ones about servants obeying masters, about accepting earthly suffering for heavenly reward.

He never anticipated that those same slaves might also pay attention to Exodus, to the prophets condemning injustice, to Jesus’s statements about freedom for captives.

By 1827, Jabari could read fluently.

More importantly, he could teach reading to others covertly.

The skills spread through the network he’d built slowly, carefully, with everyone understanding that discovery meant punishment.

Within three years, approximately 30 enslaved people on Crawford’s plantation were literate, a number that would have terrified any white person who knew about it.

And then Jabari did something that would be investigated by three separate court inquiries and eventually become the subject of legislation throughout the South.

He started writing everything down—not on paper, which would be discovered and destroyed.

He wrote in places white people never looked—on the walls of slave quarters using charcoal that could be wiped away if inspectors came, on the inside of buildings where freed slaves would eventually find it.

And most remarkably, he taught other literate slaves to do the same, creating a distributed archive of African-American memory that existed in fragments throughout the plantation.

The writings documented names, genealogies, memories of Africa, and something more dangerous—accurate records of the violence inflicted by the plantation system, dates of beatings, names of people who’d been sold and separated from families, documentation of sexual violence committed by white overseers.

This wasn’t just cultural preservation anymore.

This was evidence, testimony that could potentially be used against plantation owners if slavery ever ended or if abolitionists gained access to these records.

In 1831, something happened that changed everything.

Nat Turner led a rebellion in Virginia that killed approximately 60 white people before being suppressed with extreme violence.

The rebellion terrified white southerners throughout the region because it demonstrated that enslaved people could organize, plan, and execute coordinated violence despite the surveillance system designed to prevent exactly that.

The response was predictable: harsher laws, increased surveillance, and systematic campaigns to eliminate any education or organizing among enslaved populations.

One of the new laws prohibited teaching slaves to read or write under any circumstances.

Reverend Witmore’s literacy classes were immediately banned.

Any enslaved person found with written materials faced severe punishment, and plantation owners began conducting thorough searches of slave quarters to ensure nothing forbidden was being kept.

During one of these searches in 1832, an overseer at Crawford’s plantation found writing on the wall of a storage building.

It was in English, which meant someone literate had written it, and the content was devastating.

A list of names, dates, and descriptions of punishments inflicted over several years.

Evidence of systematic violence documented by people who’d been told they were property incapable of sophisticated thought.

The investigation that followed was extensive and brutal.

Every enslaved person on the plantation was questioned under torture about who’d written the documentation.

Several people died during these interrogations without revealing anything useful.

The white authorities were convinced this had to be the work of an outside agitator, possibly an abolitionist who’d infiltrated the plantation, because they couldn’t conceive that enslaved people might organize something this sophisticated independently.

But Samuel Crawford had a suspicion.

He remembered the African who demonstrated medical knowledge, who’d learned to read with unusual speed, who somehow seemed to be at the center of social networks among the enslaved population.

He ordered Jabari brought to the main house for questioning.

What happened during that interrogation was documented in court records from the subsequent legal proceedings.

Crawford, along with Jacob Reeves and two other white witnesses, spent three hours trying to get Jabari to confess to writing the forbidden documentation.

They used every interrogation technique available—beatings, threats, psychological pressure—and Jabari’s response was the same thing he’d been doing since 1807: he remembered.

During the interrogation, when Crawford demanded to know who had written the forbidden documentation, Jabari looked at him with the same direct eye contact that had disturbed Thomas Brennan 20 years earlier and said something that the court records preserved verbatim because everyone present found it so unsettling:

“I wrote nothing, but I remember everything.

Every name of every person you’ve brutalized, every date of every beating, every child torn from their mother’s arms and sold, every woman raped by your overseers, every man worked to death in your fields.

I carry all of it here.”

And he pointed to his head.

“You can destroy paper.

You can burn books, but you cannot burn memory.

And memory is a weapon you will never take from us.”

The room went silent.

What disturbed Crawford and the others wasn’t the defiance—they’d dealt with defiant slaves before.

What disturbed them was the implication of what Jabari was claiming.

If he’d actually memorized years’ worth of detailed records—dates, names, specific incidents—then he possessed something far more dangerous than written documentation.

He was a living archive that couldn’t be destroyed without killing him.

And even then, he’d clearly taught his methods to others.

Jacob Reeves, who’d been present during the interrogation, later wrote in his personal journal, “The Negro speaks with a clarity that suggests genuine recall rather than fabrication.

If what he claims is true, if he and others like him have systematically memorized records of plantation operations, then we face a threat unlike any rebellion.

These are witnesses who will testify against us if abolition ever comes.”

They are building a case in their minds that will condemn us.

Crawford’s response was to sell Jabari immediately, not as punishment, but as removal of a problem too complex to solve.

If Jabari was teaching memory techniques to other slaves, then killing him wouldn’t stop the spread.

But removing him from the plantation might contain the damage.

So in 1832, Jabari was sold to a slave trader named Richard Moss, who transported him to South Carolina.

This was Jabari’s third forced relocation, and he was now in his early 50s—old for an enslaved field worker.

Most enslaved men who survived to 40 had accumulated enough injuries and health problems from brutal labor that their commercial value decreased significantly.

But Jabari’s medical knowledge and his reputation for being intelligent, even if disturbingly so, meant he still commanded decent prices from buyers looking for skilled slaves rather than field hands.

The plantation he ended up on was owned by a man named George Bellamy, located about 20 miles outside Bowfort.

Bellamy ran a smaller operation than Crawford’s, only about 60 enslaved people working on mixed crops.

But he had a particular interest in what he called “negro management theory.”

Bellamy believed that the most efficient plantations weren’t those with the most brutal overseers but those that understood slave psychology and manipulated it scientifically.

When Bellamy purchased Jabari, he’d been explicitly told that this particular slave had been sold for being too intelligent and potentially corrupting other negroes with seditious ideas.

Most buyers would have avoided such a purchase.

Bellamy was fascinated by it.

He wanted to understand what made certain slaves mentally resistant to the psychological breaking that slavery required.

So he brought Jabari to his plantation, not primarily for labor, but as a kind of study subject.

The dynamic that developed between Bellamy and Jabari over the next several years was genuinely bizarre.

Bellamy would have Jabari brought to the main house several times per week for conversations where he would ask questions about African culture, slave psychology, and resistance techniques.

Bellamy framed these conversations as academic inquiry.

He was writing what he hoped would be a comprehensive manual on plantation management based on scientific understanding of negro behavior.

Jabari recognized these conversations as an opportunity.

He began teaching Bellamy deliberately false information mixed with enough truth to seem credible.

He would explain that African-born slaves were naturally incapable of complex planning, that they responded best to consistent routine and moderate discipline, that second-generation slaves who’d been properly Christianized showed no interest in African culture.

All of this was calculated to make Bellamy believe that the threat of slave intelligence and organization was overblown, that proper management techniques could eliminate any risk.

Meanwhile, Jabari was conducting his actual work among the enslaved community on Bellamy’s plantation.

Within six months, he’d established the same network he’d built on previous plantations—systematic teaching of memory preservation, African cultural education, and the creation of living archives of enslaved people’s identities and experiences.

But he added something new, something he’d been developing since his interrogation at Crawford’s plantation.

He began teaching people how to weaponize their memories.

The technique was sophisticated and drew on practices his grandfather had taught him about griot training.

A properly trained griot could recite information in ways that affected listeners psychologically, using rhythm, repetition, and emotional resonance to make stories memorable and impactful.

Jabari adapted these techniques for a specific purpose: teaching enslaved people to remember trauma so completely, so vividly that they could describe it in ways that would psychologically devastate white listeners.

This wasn’t about accuracy of facts, though that mattered.

This was about emotional truth, teaching people to access and articulate their suffering in ways that forced listeners to confront the full human cost of slavery.

The goal was to create witnesses who could testify not just to what happened, but to what it felt like to be enslaved in language so powerful that no white person could dismiss or rationalize it.

The twelve people who met with Jabari in the woods outside Bowfort in 1844 had all been trained in these techniques.

They weren’t conducting a voodoo ceremony, despite what white authorities later claimed.

They were practicing testimony, rehearsing how to describe their experiences of slavery in ways that would haunt any listener who heard them.

The two white men who discovered the gathering were brothers named Daniel and William Harding.

They’d been hunting in the woods and heard voices speaking in what they initially thought was an African language.

Curious, they approached quietly to investigate.

What they witnessed was Jabari leading what appeared to be some kind of ritual where each person stood and recited their life story in vivid, emotionally devastating detail.

The court records from the subsequent investigation include testimony from Daniel Harding describing what he heard.

The Negroes spoke about their enslavement with a precision and emotional force that seemed unnatural.

One woman described being separated from her children with such detail—the specific sounds they made when crying, the feeling of her breasts still full of milk days after they took her babies, the nightmares she still had decades later—that I found myself physically ill listening.

Another man described the Middle Passage in language so vivid that I could smell the ship’s hold, hear the chains rattling, feel the terror.

It was as if they were forcing their suffering directly into my mind.

What disturbed the Harding brothers most wasn’t the content of these testimonies, troubling as that was.

What disturbed them was the effect.

After listening for perhaps 20 minutes before revealing their presence, both men reported experiencing vivid intrusive thoughts about the experiences they’d heard described.

Daniel Harding testified that for weeks afterward, he would suddenly find himself experiencing fragments of memories that weren’t his—sensations of being chained in darkness, emotional states of grief over lost children, phantom pain from beatings he’d never received.

William Harding’s experience was more severe.

According to multiple witnesses, he began speaking in African languages he’d never learned, describing places he’d never seen, and experiencing what a doctor later diagnosed as “negro delusions,” believing himself to be an enslaved African rather than a free white man.

His condition deteriorated over several months until he required institutionalization.

The white community’s response to this incident was immediate panic.

If enslaved people had developed some kind of psychological technique that could affect white people’s minds, that could transmit trauma through mere description, then the entire foundation of slavery was threatened.

The system depended on white people being able to inflict and witness suffering without experiencing empathy or psychological consequences.

If that barrier could be broken, if slaves could make their owners feel what slavery actually meant, the moral sustainability of the institution would collapse.

Three separate investigations were launched.

The first was a local inquiry by the Bowfort County Sheriff to determine whether Jabari and the others had used some kind of African witchcraft or poison to affect the Harding brothers.

This investigation included testimony from multiple witnesses but ultimately concluded that no physical substances or supernatural forces were involved.

The second investigation was conducted by the South Carolina Medical Society, which examined William Harding and tried to understand his condition.

Their report, which still exists in the society’s archives, is remarkable for its honesty about what they found.

The patient exhibits symptoms consistent with having experienced traumatic events he could not have personally lived through.

When questioned about this capability, several mentioned having been taught memory techniques by an African man they refer to respectfully as “the teacher” or “the rememberer.”

They describe him as someone who believed that preserving accurate testimony was a moral obligation and a form of resistance.

The third investigation was conducted by the state legislature, which convened a special committee to assess whether new laws were needed to prevent whatever Jabari had done.

This committee heard testimony from plantation owners throughout the region, consulted with ministers and doctors, and ultimately produced a report that recommended sweeping changes to how enslaved people were managed.

The report’s key finding was buried in the middle of a long document, but it was devastating in its implications.

We conclude that the teaching of memory techniques to slaves, combined with their systematic documentation of plantation operations and their development of methods for vividly describing their experiences, represents a threat to public order that requires immediate legislative action.

If enslaved populations can preserve detailed records of their treatment and transmit these records through oral tradition, they create evidence that could be used against slaveholders in the event of abolition or federal intervention.

More immediately, if slaves can affect white citizens psychologically through sufficiently vivid descriptions of their suffering, they possess a weapon that conventional plantation management cannot neutralize.

The legislation that followed, passed in South Carolina in 1845 and adopted in modified form by several other southern states, included provisions that specifically targeted the kind of resistance Jabari had pioneered.

It prohibited teaching enslaved people any memory techniques or mnemonic systems.

It made it illegal for more than three slaves to meet privately without white supervision.

It required plantation owners to rotate slave populations regularly to prevent the formation of long-term communities where knowledge could be preserved across generations.

And most tellingly, it mandated the separation or sale of any enslaved person identified as possessing unusual intelligence or capability for organized resistance.

George Bellamy, whose plantation had been the site of the 1844 incident, faced significant social pressure from other plantation owners.

They viewed him as having been dangerously naive in allowing Jabari extended contact with other slaves and access to the kind of freedom that enabled organizing.

The expectation was that Bellamy would make an example of Jabari—a public execution or at minimum a punishment severe enough to terrify any other enslaved people considering similar resistance.

But Bellamy did something that surprised everyone.

He refused to have Jabari killed.

His reasoning, preserved in a letter to his brother, revealed something important about how certain white people understood the threat Jabari represented.

“If we kill him, we make him a martyr and confirm that his methods are powerful enough to frighten us.

If we torture him publicly, we prove that psychological resistance warrants the same violent response as physical rebellion, which validates his approach.

The most effective response is to contain him while publicly dismissing his influence as overblown hysteria.”

So instead of execution, Bellamy sold Jabari to a man named Edmund Hail, who ran a small plantation in the interior of South Carolina with only about 20 enslaved people.

The expectation was that Jabari would be isolated on a small plantation where his influence would be minimal and where Hail, who’d been warned about Jabari’s history, would keep him under strict surveillance.

This was 1845.

Jabari was now in his mid-50s.

He’d been enslaved for 38 years, survived four different plantations, witnessed countless acts of brutality, lost contact with everyone he taught in previous locations, and endured decades of systematic attempts to break his will.

Any reasonable person would have been psychologically destroyed by this accumulation of trauma.

Any normal human being would have surrendered to despair.

But Jabari wasn’t normal.

He’d spent 38 years practicing and refining techniques for psychological resistance that transcended anything the slave system had encountered before.

And Edmund Hail’s plantation, small and isolated as it was, would become the site of the final phase of Jabari’s life work, something that would be talked about in whispers among enslaved communities throughout the South for generations afterward.

Edmund Hail’s plantation was different from the large industrial operations Jabari had experienced.

With only 20 enslaved people, everyone knew each other intimately.

There was no anonymity, no way to conduct secret meetings or organize without Hail becoming aware of it.

Hail himself lived on the property in a house that overlooked the slave quarters, and he personally supervised most work rather than relying on overseers.

For someone trying to organize resistance, this surveillance state should have been impossible to work within.

Jabari’s solution was brilliant in its simplicity.

He stopped trying to organize anything that looked like resistance from an external perspective.

Instead, he focused entirely on teaching a single practice that could be done individually, silently, and in ways that no surveillance could detect.

He taught people how to meditate on their memories in ways that preserved identity while processing trauma.

This practice drew on techniques his grandfather had taught him, adapted through nearly four decades of experience with slavery’s psychological impact.

The core principle was that memories of trauma needed to be acknowledged and preserved rather than suppressed, but they needed to be held in ways that didn’t destroy the person carrying them.

You had to remember the Middle Passage without letting that memory prevent you from experiencing joy.

You had to preserve the knowledge of family members sold away without being paralyzed by grief.

You had to maintain awareness of systematic injustice without succumbing to hopelessness.

The technique involved what Jabari called witnessing, a practice where you would sit quietly, typically late at night when no one was watching, and deliberately recall specific traumatic memories while maintaining emotional distance.

You would describe the memory to yourself in detail, acknowledging what happened and how it felt, but framing yourself as an observer documenting events rather than a victim being destroyed by them.

This created psychological space between your core identity and the trauma you’d experienced, preventing the trauma from completely defining who you were.

Western psychology wouldn’t develop similar techniques until more than a century later, when therapists working with trauma survivors would independently discover that controlled exposure to traumatic memories in safe contexts could reduce their psychological impact.

But Jabari had developed this practice through his own experimentation with managing the psychological damage of slavery, refined through decades of teaching others and observing what worked.

The 20 enslaved people on Hail’s plantation learned this practice from Jabari over the course of several years.

It required no group meetings, no suspicious gatherings, no obvious organizing.

Jabari would simply work alongside someone in the fields and speak quietly about the technique.

“Tonight, when you’re alone, think about the worst thing that ever happened to you.

Not to dwell in the pain, but to witness it.

Tell yourself the story as if you’re describing it to someone who needs to understand.

And then remind yourself that happened to you, but it is not all of you.

You exist beyond what they did to you.”

The practice spread because it worked.

People who engaged in this systematic witnessing reported feeling less crushed by their memories, better able to maintain hope despite their circumstances, more connected to who they’d been before enslavement.

And crucially, the practice was self-sustaining.

Once you learned it, you could continue independently.

You didn’t need Jabari’s presence or anyone else’s.

The resistance existed entirely within your own mind.

Edmund Hail noticed changes in his enslaved population that troubled him.

They weren’t rebellious or defiant in any obvious way.

They worked adequately and followed instructions, but there was something about their psychological state that felt wrong to him.

They seemed less broken than slaves should be, less defeated.

They maintained a kind of dignity that properly managed slaves weren’t supposed to have.

Hail’s letter to his brother, the one found hidden in the wall of his demolished house in 2019, was written during this period.

The fear he expressed wasn’t about physical rebellion.

Jabari was in his 50s and didn’t seem to be plotting escape or violence.

The fear was about something more fundamental.

Hail had begun to suspect that this particular African possessed knowledge about psychological resistance that made conventional slavery impossible, that the very presence of someone who could teach others how to preserve their minds despite enslavement represented an existential threat to the system.

“I cannot explain it clearly,” Hail wrote.

“But this negro looks at me with eyes that have seen things I cannot imagine and remembers things I would prefer forgotten.

He makes me feel that I am the one being judged.

That history will view my actions differently than I view them myself.

And worse, he has taught this same awareness to the others.

They are slaves in body but free in mind.

And I do not know how to break something I cannot physically touch.”

The letter ended with a confession that revealed more about the psychological cost of slavery to white people than most historical documents ever acknowledged.

“I dream about the things they have experienced.

I wake in the night convinced I am chained in darkness, that I am being beaten, that my children are being sold.

I think he has cursed me somehow.

But the curse is simply forcing me to imagine what slavery means to those who endure it.

I cannot continue this way.

I must sell him before he drives me mad.”

But Hail never sent the letter.

And he never sold Jabari because by the time he’d written it, something had shifted in him that made it impossible to continue plantation operations as before.

Within a year of writing that letter, Hail freed all 20 enslaved people on his plantation, sold his property, and moved to Pennsylvania, where he became a vocal abolitionist.

His explanation for this radical transformation, given in speeches he delivered throughout the 1850s, was remarkably simple.

“I met a man who taught me to see what I had been deliberately refusing to acknowledge.

And once I saw it clearly, I could no longer participate in the system.”

Jabari Mansa was freed in 1846 at age 56.

He was one of approximately 20,000 free black people living in South Carolina at that time, navigating a society that viewed their existence as dangerous and their freedom as provisional.

Free black people in the antebellum South faced constant surveillance, restrictions on travel and assembly, and the ever-present threat of being kidnapped and sold back into slavery if they couldn’t prove their free status.

But Jabari had something most free black people lacked: decades of practice in organizing and teaching under surveillance, a vast network of knowledge that existed in the minds of hundreds of people he taught across four plantations, and a skill set for psychological resistance that he could now share more openly.

The final 18 years of Jabari’s life—from 1846 until his death in 1864—are documented in fragments that historians have pieced together from various sources.

He lived in Bowfort, working as what would now be called a community organizer and educator.

He taught literacy to free black children and adults who sought him out.

He conducted what he called “remembering circles,” where people would share their experiences of slavery and practice the witnessing techniques he developed.

And he served as what amounted to a living library.

Anyone who wanted to know about African culture, about their family history, or about the realities of slavery that white historians were already beginning to sanitize could come to Jabari and learn.

More importantly, he trained others to continue his work.

By the time of his death in 1864, months before the Civil War ended slavery throughout the United States, Jabari had created a network of approximately 200 people across three states who practiced his memory preservation techniques and who taught them to others.

These people became the foundation for what would eventually evolve into the oral history tradition that kept African-American experiences alive despite systematic attempts to erase them from official records.

Jabari Mansa died on March 15, 1864, in a small house in Bowfort, South Carolina, surrounded by people he’d taught.

The cause of death was recorded as pneumonia, but several witnesses later said he’d simply decided it was time to stop.

He’d lived 57 years as an enslaved person and 18 years as a free man.

He’d survived the Middle Passage, four different plantations, countless beatings, and decades of systematic attempts to break his mind.

And in the end, he died with something that most enslaved people never got: the certainty that his life’s work would outlast his body.

The funeral was attended by nearly 300 people—a gathering large enough that local authorities considered breaking it up as a potential security threat.

Free black assemblies of that size were illegal in South Carolina, but the local sheriff made a calculated decision not to intervene.

The war was clearly ending.

Slavery’s days were numbered, and creating martyrs at this point seemed counterproductive.

So the funeral proceeded, and what happened during that gathering would be remembered and repeated in black communities throughout the South for the next century.

Seventeen different people stood and recited portions of what Jabari had taught them—not speeches or eulogies in the traditional sense.

They recited genealogies, the complete family histories of enslaved people that Jabari had memorized and preserved.

Names going back generations, origins in specific African regions, cultural practices that had been maintained despite slavery’s attempts to erase them.

Each recitation took 10 to 15 minutes, and collectively they represented something unprecedented: a public demonstration that enslaved people’s histories had not been lost, that the cultural genocide slavery intended had failed, that witnesses existed who would testify to what had been stolen.

A woman named Charlotte, who’d been freed two years earlier, stood and recited the names of 47 people who’d been sold from George Bellamy’s plantation between 1832 and 1845.

She spoke each name clearly, gave the date of their sale, described where they’d been taken, if that information was known, and listed family members they’d been separated from.

The recitation took 20 minutes.

When she finished, she said simply, “Jabari taught me to remember these people so they would not disappear from history.

They were here.

They existed, and we bear witness.”

A man named Isaac, who’d learned to read through Jabari’s teaching, read from a document he’d written, a detailed account of punishments inflicted on Crawford’s plantation in Alabama over a 15-year period—names of people who’d been whipped, dates of the beatings, descriptions of injuries.

He’d compiled this document based on what Jabari had taught him and what he’d remembered himself.

And he announced that copies of this testimony would be preserved and eventually delivered to federal authorities investigating slavery’s conditions.

One after another, people demonstrated what Jabari had created: a systematic archive of slavery’s realities, preserved in human memory and now being transferred to written records that could survive permanently.

This wasn’t celebration or mourning in the conventional sense.

This was documentation.

Evidence presented publicly for the first time because the people carrying it finally felt safe enough to speak.

The local white community’s response to this funeral tells you everything about why Jabari’s story had to be erased.

Several people who attended wrote letters to relatives or kept diary entries describing what they’d witnessed.

These documents scattered across various historical archives revealed genuine terror at what they’d seen.

A plantation owner named Robert Hutchinson wrote to his brother, “They have been keeping records—detailed, accurate records of everything that has been done to them, names, dates, specific incidents.

If this information reaches northern authorities or is published in abolitionist newspapers, every slaveholder in the South could face criminal prosecution.

More immediately, if this is what one African accomplished through teaching memory techniques, we must confront the possibility that hundreds or thousands of enslaved people possess similar knowledge.

We have been documenting our own crimes without realizing our victims were doing the same.”

A Methodist minister named Reverend James Sullivan, who’d attended the funeral out of curiosity, wrote in his diary, “I witnessed something today that shook my understanding of what we have done.

These people spoke about their enslavement with a precision and detail that made clear they have been conscious witnesses to their own oppression, not the unthinking laborers we convinced ourselves they were.”

And the African who taught them this witnessing, who spent decades training people to remember and testify, has created something we have no defense against.

Truth preserved beyond our ability to suppress it.

Within two weeks of Jabari’s funeral, a coordinated campaign began to suppress any discussion of what had happened there.

Local newspapers that had initially reported on the funeral were asked to print corrections, suggesting the crowd had been smaller and the testimonies less detailed than initially reported.

Ministers were instructed not to discuss the incident from their pulpits.

And most tellingly, plantation records throughout the region began to be systematically destroyed.

Ledgers that documented punishments, sales, and operational details were burned or lost in ways that suggested deliberate elimination of evidence.

This suppression campaign extended beyond South Carolina.

In Alabama, when authorities learned that enslaved people trained by Jabari had been documenting plantation operations, multiple properties experienced mysterious fires that destroyed their record-keeping buildings.

In Georgia, several free black people who’d been known to practice Jabari’s memory preservation techniques were arrested on fabricated charges and forcibly relocated to areas where they had no existing community connections.

The goal wasn’t just to prevent prosecution of individual plantation owners.

The goal was to erase evidence that enslaved people had maintained consciousness throughout their bondage, had been witnesses rather than victims, had preserved testimony that could be used against the entire system.

Because if that evidence became public, if northern abolitionists and federal authorities gained access to the kind of detailed accounts that Jabari had taught people to preserve, the South’s defense of slavery as a benign institution that enslaved people accepted as natural would collapse completely.

But here’s what the people trying to suppress this story didn’t understand.

You can’t erase something that exists in hundreds of minds scattered across multiple states.

You can burn documents.

You can silence individual witnesses, but you can’t destroy knowledge that’s been distributed through a network designed specifically to survive exactly this kind of suppression attempt.

The memory preservation network Jabari created continued functioning after his death, and it evolved in ways that even he probably didn’t anticipate.

During Reconstruction, when formerly enslaved people began testifying before federal authorities about slavery’s conditions, an unusual number of witnesses from South Carolina, Alabama, and Georgia provided testimony that was remarkably detailed and consistent.

They could recite specific dates, name individual perpetrators, describe incidents with the kind of precision that made their accounts legally credible rather than dismissible as emotional exaggeration.

Federal investigators noticed this pattern but couldn’t quite understand it.

How were formerly enslaved people, most of whom were illiterate and had been deliberately isolated from information, able to provide testimony that read like legal depositions?

The answer, which a few investigators eventually pieced together, was that they’d been trained by someone who understood that memory could be weaponized, that witnessing could be a form of resistance, and that the best way to ensure justice was to create witnesses who couldn’t be discredited.

In 1872, a federal investigator named Samuel Harrison interviewed approximately 50 formerly enslaved people in South Carolina about their experiences.

His report, buried in the National Archives until a historian rediscovered it in 1998, includes this observation.

“I have encountered an unusual phenomenon among the freed people in this region.

Many possess an ability to recall details of their enslavement with extraordinary precision.

When questioned about this capability, several mentioned having been taught memory techniques by an African man they refer to respectfully as ‘the teacher’ or ‘the rememberer.’

They describe him as someone who believed that preserving accurate testimony was a moral obligation and a form of resistance.”

The impact of his teaching appears to have created a generation of witnesses whose accounts will prove invaluable in documenting slavery’s true nature.

But Harrison’s report was never published.

The political climate of the 1870s was shifting against Reconstruction.

Northern commitment to protecting freed people’s rights was weakening.

Southern whites were regaining political power.