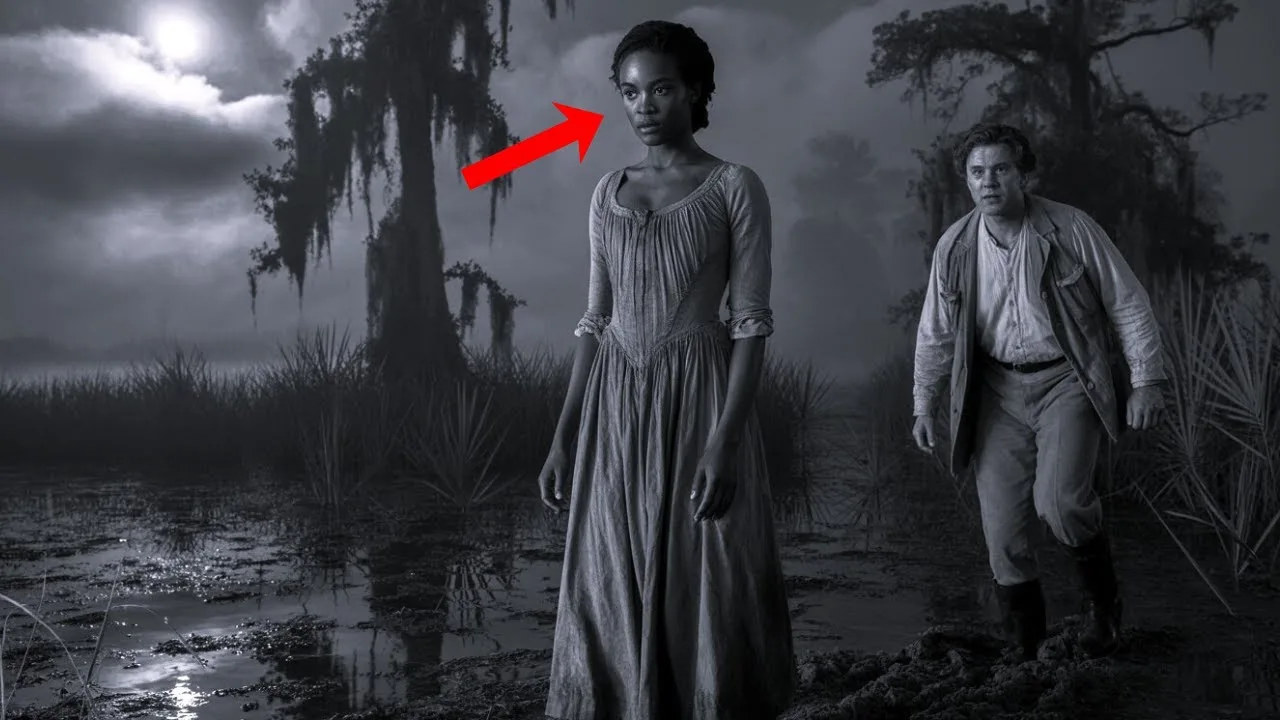

A slave girl pretended to love the overseer, but every word, every touch, every whispered promise was a calculated weapon designed to lead him into a swamp of psychological traps he’d never escape. This is the story of how she turned the tables on the man who held her captive, using the one thing he never saw coming, his own loneliness and desperate need to be loved.

What starts as a dangerous game of manipulation becomes something far more complex. tale of survival, sacrifice, and the devastating question of whether love can exist in the midst of calculated deception. The plantation stretched across endless acres of red clay and suffering. The sun beat down mercilessly, turning the earth into an oven, and the air tasted like sweat and desperation.

Marcus Thorne ruled this hell with an iron fist and a cruel smile. He was the overseer, the man who stood between the enslaved people and whatever scraps of mercy might exist in this god-for-saken place. But mercy was a language he never learned. Every morning he woke up and chose violence.

Every evening he fell asleep satisfied with the destruction he caused. He was 47 years old, weathered by years of brutality, and he carried the weight of his cruelty like a badge of honor. But here’s what nobody knew about Marcus Thorne. Beneath the cruelty, beneath the whip and the commands and the absolute power he wielded, he was profoundly, devastatingly lonely. He had no friends.

The plantation owner kept him at arms length. The enslaved people feared him rightfully so, and the few women he de pursued had either fled or been broken by his approach. He didn’t he know how to connect with people. He only knew how to dominate them. So every night he sat alone in his quarters drinking whiskey that burned his throat, wondering why power felt so empty.

This is where entered his life. She was 24 years old, born into slavery on this very plantation. Her mother had died when she was 12. Her father had been sold away before she could even remember his face. She watched friends get whipped for minor infractions. She de seen children separated from their mothers.

She des survived things that should have broken her mind. But had something that most people didn’t t she was a reader of people. While other enslaved workers focused on survival on getting through the day without attracting attention to studied. She watched Marcus. She observed his patterns, his moods, his vulnerabilities.

She noticed how he lingered near the quarters in the evening. She saw how his eyes would soften when he thought no one was looking. She understood that beneath the brutality, there was a man starving for connection. And she made a decision that would change everything. She decided to give him exactly what he was starving for. It started small.

A glance, a moment where their eyes met across the plantation, and she didn’t te look away immediately. She held his gaze for just long enough to make him wonder if he deimagined it. Then came the conversations. Allah began positioning herself where Marcus would encounter her. When he passed, she speak not with submission but with intelligence.

She dee asked him questions about his day. She listened to his complaints about the plantation owner with genuine interest. She laughed at his jokes, even the ones that weren’t tea funny. Marcus had never experienced this before. A woman who seemed genuinely interested in him.

A woman who didn’t he flinch when he approached. A woman who made him feel like maybe just maybe he wasn’t he completely irredeemable. But what Marcus didn’t he know was that had been studying him for months, waiting for the perfect moment to strike. She knew his schedule better than he did. She knew which days he drank more heavily.

She knew when he was vulnerable. She knew exactly how to position herself to catch his attention and more importantly, she knew how to keep it. The psychological game had begun and Marcus was already losing. By the third week, Marcus was seeking her out. He defined reasons to be near the quarters where worked.

He did linger longer than necessary during morning inspections. He dee manufacture excuses to speak with her asking about her tasks, her well-being, her thoughts on trivial matters. It was transparent to everyone watching, but Marcus didn’t he care. For the first time in years, he felt alive. All played her role flawlessly.

She mirrored his emotions with surgical precision. When he was angry about the plantation owner s demands, she validated his frustration. When he boasted about his authority, she listened with admiration in her eyes. when he complained about his loneliness, which he eventually did, she made him feel understood in a way no one had ever managed before.

“You carry so much weight,” she told him one evening when he de called her to his quarters under the pretense of discussing work assignments. Everyone sees the overseer. No one sees the man beneath. Marcus stared at her, his whiskey glass frozen halfway to his lips. No one had ever said anything like that to him.

No one had ever looked at him the way she was looking at him now. Not with fear, not with contempt, but with something that looked remarkably like compassion. “You understand me,” he said quietly. “I do,” Ara replied. “And she meant it. She understood him perfectly. She understood his need for validation.

She understood his desperate hunger to be seen as something other than a monster. She understood that he was a man built entirely on the foundation of power, and without it, he would crumble.” She was right. Over the following weeks, Marcus became emotionally dependent on her. He granted her privileges that other enslaved people could only dream of lighter work assignments, extra rations of food, protection from the worst of the plantation as cruelties.

He gave her access to his quarters. He began sharing his secrets with her. He told her about the embezzlement scheme he was running, skimming money from the plantation. Owner s profits. He told her about his fears that one day he’d be discovered and cast out with nothing. He told her about the swamp that bordered the plantation, how he explored it extensively.

How he knew its hidden paths and secret clearings where a man could disappear if he needed to. Every confession was a gift to Ara. Every secret was another thread in the trap she was weaving. But something unexpected happened. As Allara performed her role with increasing perfection, the performance began to crack her own sense of self.

She found herself thinking about Marcus when she wasn’t tea with him. She dee catch herself smiling at something he de said days earlier. She do wonder what he was doing, how he was feeling, whether he was thinking of her. One night, lying on her thin mattress in the quarters she shared with other enslaved women, Allar realized with terrifying clarity that she was losing track of where the act ended and reality began.

This wasn’t tea supposed to happen. The plan was simple. Seduce the overseer, gain his trust, gather intelligence, and then execute the escape that had been years in the making. There was no room in the plan for genuine feeling. There was no space for complications. But Marcus had somehow managed to slip past her defenses.

He wasn’t te just a target anymore. He was becoming a person to her a lonely, broken person who had done terrible things, but who was in his own way a victim of the system that had shaped him. All caught herself thinking dangerous thoughts. What if they could actually escape together? What if she could help him become someone better? What if the love she was pretending to feel could somehow become real? She knew these thoughts were poison.

They would destroy everything, but she couldn’t te stop them. One evening, Marcus held her close in his quarters, and he whispered something that made her heart stop. I want to take you away from here. I’ve been saving money. In another year, maybe two, we could disappear into the swamp.

We could start a new life somewhere no one knows us. We could be free together. Elara s breath caught in her throat. This was it. This was the moment she’d been working toward. Marcus was offering her the key to escape, wrapped in the fantasy of romantic destiny. But as she looked into his eyes, she saw something that made the trap she deconstructed feel suddenly fragile. Hope.

Pure, desperate, beautiful hope. And she realized that the bigger problem wasn’t t maintaining the act. The bigger problem was that she was starting to feel something genuine for the man she was about to destroy. Allah didn’t te answer him that night. She couldn’t tee. Instead, she rested her head against his chest and listened to his heartbeat.

Each pulse a reminder of the humanity she’d been trying to ignore. The next morning, everything changed. A messenger arrived from the state capital with news that rippled through the plantation like poison through water. New laws were being enacted. stricter regulations on enslaved people, harsher punishments for escape attempts, and most importantly, a mandatory audit of all plantation finances within the month.

Marcus s face went white when he heard the embezzlement scheme he confessed to the one that was supposed to fund their escape was about to be discovered. The plantation owner would find the discrepancies. There would be investigations. Marcus would be ruined, possibly arrested, certainly cast out without a penny.

He came to Ara that evening in a state of panic she’d never seen before. “We have to leave,” he said, gripping her shoulders. “Not in a year, not in 2 years. Now, tonight we take what we can carry and we disappear into the swamp. I know the way. I know places where no one will ever find us.” This was the moment.

This was exactly what had been orchestrating all along. But when she looked at Marcus really looked at him, she saw a man on the edge of destruction. Not the cruel overseer, not the calculating manipulator, just a man who was about to lose everything and who believed that she was the only thing worth saving. “Okay,” she said softly.

“We leave tonight.” They made their preparations in secret. Marcus gathered supplies, food, water, a rifle, ammunition, money he dee hidden away. He forged travel papers in case they encountered anyone on the road. He moved with the efficiency of a man who dee clearly thought about escape before, even if he dee never believed he actually do it.

As darkness fell, they slipped away from the plantation. But carried a secret that Marcus didn’t he know. She wasn’t te running away with him. She was running away from him. Hidden in her small bundle of possessions was a detailed map of the plantation written in her careful hand. It documented every building, every path, every vulnerable point.

She d been creating it for months, gathering information through careful observation and through the conversations she extracted from Marcus during their intimate moments. She also carried the names and locations of three other enslaved people who were ready to escape people she’d dee been quietly organizing while performing her role as the devoted lover.

They were waiting at a predetermined meeting point in the swamp, armed with the knowledge that would help them navigate to freedom. The plan had never been to escape with Marcus. The plan had always been to use him. They walked through the darkness for hours, moving deeper into the swamp. Marcus led the way with confidence, following paths only he seemed to know.

Ara followed, her mind racing through the logistics of what came next. When they reached the clearing where she de arranged to meet the others, Marcus finally understood. The three figures emerged from the shadows. Two men and one woman, all enslaved people from the plantation.

They were carrying supplies and weapons. They looked at Marcus with expressions ranging from fear to anger to grim determination. “What is this?” Marcus asked, his hand instinctively, moving to the rifle he carried. “This is freedom,” Allar said quietly. “But not the kind you imagined.” She explained it to him then all of it.

How she’d been studying him for months before she ever approached him. How every conversation, every touch, every moment of intimacy had been calculated. How she dee used his loneliness against him. How she de extracted information that would help dozens of people escape. How the three people standing before them were just the first group there would be others guided by the knowledge she de gathered.

“I used you,” she said, and there was no apology in her voice, only truth. “I used your need to be loved. I used your desire to escape. I used every vulnerability you showed me, and I would do it again because what I’ve accomplished will help more people find freedom than you could ever understand.

” Marcus stared at her, and the expression on his face cycled through shock, betrayal, anger, and final something that might have been recognition. “You never loved me,” he said. “No,” Arara replied. I didn’t te but I understand you better than anyone ever has and that understanding was the most powerful weapon I could have used against you.

There was a moment of terrible tension. Marcus s hand tightened on the rifle. The others tensed, ready for violence. The air seemed to hold its breath, but Marcus lowered the weapon. What happens now? He asked. Now, said, you have a choice. You can come with us and help us guide others to freedom.

You can use your knowledge of these lands to save lives instead of destroy them. Or you can go your own way and we’ll part as enemies. Marcus looked at the three people standing with Aara. He looked at the woman he thought he loved who had systematically dismantled his entire sense of self.

He looked at the rifle in his hands, at the swamp stretching out before them. At the life he’d denown crumbling away behind them. If I come with you, he said slowly. What does that make me? A man who finally has the chance to become something other than what he was, ara answered. Marcus was quiet for a long moment.

Then he set down the rifle. Show me the way, he said. The swamp was a living thing breathing, shifting, dangerous in ways that went beyond the physical. As they moved deeper into its heart, Marcus began to understand that escaping the plantation was the easy part. The real escape was learning to exist in a world where the rules he deived by no longer applied.

For the first 3 days, they traveled in silence. The group moved cautiously, following routes that Marcus had once used for solitary exploration, but had never imagined using for something like this. Ara walked near the back, occasionally consulting the mental map she deconstructed of the surrounding territories. The swamp seemed to recognize them as intruders, constantly testing their resolve with obstacles fallen trees that blocked their path, water that rose unexpectedly, insects that swarmed without warning. Marcus led them through it all with the precision of someone who had spent years studying this landscape. He knew which water was safe to drink and which was brackish and poisonous. He knew which plants could be eaten and which would cause hallucinations or death. He knew the sounds of the swamp which were natural and which signal danger. But knowledge wasn’t tea the same as belonging. And Marcus was beginning to realize that he would never

truly belong anywhere again. The other three, Samuel, Thomas, and Grace watched Marcus constantly. They didn’t he trust him? Why would they? He was the man who had wielded the whip. He was the embodiment of their oppression. That he was now walking with them toward freedom. Didn’t he erase years of cruelty? Samuel was older than the others, maybe 50, with scars on his back that told stories of decades of brutality.

He moved with the careful deliberation of someone who had learned that one wrong step could mean death. Thomas was lean and muscular with the coiled tension of someone who de learned to survive through constant vigilance. Every sound made him tense. Every shadow made him ready to run or fight.

Grace was younger, perhaps 20, with sharp eyes that missed nothing. She had been born into slavery on the plantation, had never known freedom, and yet she moved through the swamp with a kind of grace that suggested she had been preparing for this moment her entire life. On the fourth night, they made camp on a small island of dry ground.

Surrounded by murky water, a fire burned low, casting shadows that made everyone look like ghosts of themselves. The mosquitoes were relentless, and the air hung heavy with moisture and decay. The sounds of the swamp at night were unlike anything Marcus had experienced during his daytime exploration’s distant calls that might have been animals or might have been something else entirely.

splashes in the water that suggested movement just beyond the reach of their fire light. “We need to talk about what comes next,” Samuel said, his voice cutting through the ambient noise of the swamp. He settled himself carefully on a log, his movements deliberate and economical. “We can te just wander the swamp forever. We need a destination.

We need a plan. Otherwise, we were just postponing the inevitable.” “The inevitable being what?” Marcus asked, though he already knew the answer. Capture, Thomas said bluntly. Death, recapture, and a worse fate than death. The plantation owner one te stopped looking for us. El send hunters. He’ll offer rewards.

Eventually, they’ll find us. There are safe houses, Grace said. She was sitting closest to the fire, her face illuminated by the flickering flames. Communities of free people up north. I’ve heard stories whispered conversations between enslaved people when the overseers weren’t tea listening. There are places where people like us can disappear, where we can build new lives.

How far north? Marcus asked. Weeks of travel, Grace replied. Maybe months. The journey itself is dangerous. There are slave catchers everywhere. There are towns that are hostile to runaways. But there are also people who help, people who believe in freedom. All eyes turned to Marcus as if he were supposed to have the answers.

“What?” he asked, though he already knew. “You have money?” Thomas said bluntly. He leaned forward, his voice low and intense. “The money you stole from the plantation owner. Money that came from the labor of people like us people who worked without compensation, without choice, without hope. That money is our way north.

That money is our chance at freedom. I don’t te have it with me. Marcus said it’s his hidden on the plantation. Then we go back. Samuel said it wasn’t he a question. It was a statement of fact delivered with the certainty of someone who had already made the decision. That is suicide. Marcus replied, his voice rising slightly.

The moment we return, we’ll be captured. The plantation owner will have guards posted everywhere by now. He’ll know we’ve have escaped. He’ll be expecting us to come back for supplies, for money, for something. It’s a trap. Then we retrapped, Grace said flatly. She said it without emotion, as if she were simply stating an obvious truth.

We were trapped in this swamp with no money, no resources, and no way to reach the communities up north. We all die here slowly from hunger or disease or exposure. Allah had been silent throughout this exchange, sitting on the edge of the group, seemingly absorbed in the task of sharpening a knife on a stone.

But now she spoke, her voice cutting through the tension like that knife through flesh. We renot trapped. I know where he keeps it. Everyone turned to look at her during one of our times together. she continued, her voice steady. And matter of fact, Marcus showed me he was drunk and wanted to impress me with how clever he was.

He wanted me to understand how resourceful he was, how he D managed to accumulate wealth despite his position. There’s a loose floorboard in his quarters beneath the bed. He keeps the money in a metal box. He showed me exactly where it was, even demonstrated how to remove the board without making noise.

Marcus felt something twist in his chest. A sensation that was part shame, part rage, part something he couldn’t te quite identify. Even now, even after everything, she was using information he de given her in moments of vulnerability and intimacy. I can get it. All said, I can go back alone. I’m less likely to be suspected than any of you.

The plantation owner knows that I escaped with Marcus, but he doesn’t he know how far I’ve gone. If I return alone with a story about how I was separated from the group, how I managed to escape back to the plantation seeking shelter and forgiveness, they might believe me. They might let me back in.

And once I am inside, I can retrieve the money. That’s too dangerous, Marcus said immediately. His voice was sharp, almost desperate. You don’t te know what they’ll do to you if they catch you. They’ll punish you for escaping. They’ll make an example of you. They might. He couldn’t te finish the sentence. He couldn’t te articulate all the horrible things that might happen to her if she was captured.

Ara looked at him with an expression that was almost pitying. You don’t te get to protect me anymore, Marcus. You never really did. You only ever controlled me. You made decisions that affected my life based on what you wanted, what you needed, what made you feel powerful. There’s a difference between protection and control.

And you never learned that difference. She was right, and he knew it. Everything she said was true, and the truth of it cut deeper than any physical wound could have. Samuel cleared his throat. If you go back, he said to Arara, “You need to understand the risks. They might recognize you immediately as a runaway. They might torture you for information about where we are.

They might use you as bait to trap us. I understand the risks, said calmly. I’ve thought about this extensively. I’ve been planning for this possibility since the moment I decided to escape. I have a story prepared. I have details that will support my story. I know the plantation s routines, the guards schedules, the best time to move through the buildings without being seen.

I can do this. And if you can, T Grace asked quietly. If something goes wrong and you recaptured, then I’ll die knowing I tried to do something that mattered. All said simply, “And you will have to find another way north. But I believe I can do this. I believe I can get the money and escape again.

” They argued for hours. Thomas insisted it was too risky. Samuel wanted to find another way to move north without the money to rely on the goodwill of the communities that supposedly helped runaways. Race was quiet, but her silence suggested she understood the logic of Arara s plan even if she didn’t te like it.

Marcus argued the hardest. He argued from a place of genuine fear, not fear for himself, but fear for Ara. Hedi spent so long thinking of her as a tool, as a means to an end that Hedi almost forgotten she was a person, a person who could be hurt, a person who could die. But was unmoved by his arguments.

She listened to them all, acknowledged them, and then calmly explained why they didn’t he matter. The only way forward, she said, is through. And the only way through is if we have resources. The money is necessary. I am the only one who can get it. Therefore, I have to go back. The logic was airtight.

And by the time the night ended, even Marcus had to admit that she was right. Before she left the next morning, Marcus tried to speak with her privately. He waited until the others were occupied with breaking camp and preparing supplies. Then he approached her at the edge of the small island. “Why are you doing this?” he asked.

“You have your freedom now. You could disappear. Start a new life somewhere far away. You could vanish into the wilderness and never look back. Why risk going back to the plantation? Why put yourself in danger? All was checking her supplies, a small knife, a change of clothes, a bundle of food wrapped in cloth.

She didn’t te look up at him as she answered. Because, she said, freedom for three people isn’t tea freedom. It’s just survival. And I am done surviving. I want to build something. I want to help others escape. I’ve been thinking about this for years, Marcus. I’ve been thinking about how to create a network, a system of safe houses and guides and resources that could help people like us find their way to freedom.

The money is just the beginning. With the money, we can establish ourselves in a community up north. We can create a station on the Underground Railroad. We can become part of something larger than ourselves. She finally looked up at him and her eyes were bright with purpose. I want to free hundreds of people, Marcus. Maybe thousands.

I want to create something that will outlast me that will continue to help people long after I am gone. The money is the key to that and I’m willing to risk my life for it because it s worth more than my life. It’s worth more than any individual life. And if you recaught, Marcus pressed, if you recaptured and tortured and executed, what happens to your grand plan then? Then someone else will take it up.

Ara said the work is bigger than any one person. That’s the whole point. If I fail, others will succeed. If I die, my death will mean something because it will have been in service of something real. Marcus reached out to touch her face, but she stepped back. Dante, she said. Dante tried to make this romantic.

Danty tried to pretend that what we had was real or meaningful in some transcendent way. We both know the truth. You loved the woman you thought I was. I used the man you were. I manipulated you, deceived you, and extracted information from you that I am now using to escape and to help others escape.

That’s the only honest thing between us. That’s the only truth that matters. I could have loved the real you,” Marcus said quietly. “If I did known who you really were, if you de let me see the real you, I could have.” No, interrupted. You couldn’t he have? Because the real me is someone who would manipulate you without hesitation to save her people.

The real me is someone who sees you as a tool, not a person. The real me is someone who would do it all again exactly the same way without a moment of regret or hesitation. That’s not someone you could love. That’s someone you should fear. That’s someone you should respect for her willingness to do what needs to be done, but never love.

She picked up her bundle of supplies and turned to leave. Wait, Marcus said, “Please, I need to know something. When you were with me, when we were together in my quarters, was any of it real? Was there any moment where you felt something genuine?” All paused. And for just a moment, something flickered across her face, a shadow of something that might have been regret or might have been pity.

“No,” she said finally. “There wasn’t tea. It was all performance. Every kiss, every touch, every word of affection was calculated. I was always thinking about my next move. Always analyzing your reactions. Always adjusting my approach based on what I learned. I never stopped performing. Not for a moment. And I never will.

She left before dawn, disappearing back toward the plantation like a ghost returning to haunt the living. The days that followed were the longest of Marcus S’s life. Samuel, Thomas, and Grace barely spoke to him. They maintained a distance both physical and emotional. They made it clear through their actions that they were tolerating his presence only because Aara had vouched for him and because they needed him to guide them through the swamp if something went wrong. Samuel in particular seemed to regard Marcus with a mixture of contempt and curiosity. One evening as they sat around the fire, Samuel asked him a question. Why didn’t TU stop her? You were the one with the rifle. You were the one with the power. Why didn’t TU just refuse to let her go back? Because, Marcus said slowly, she was right. And because I don’t he have the right to make decisions for her anymore. I spent years making decisions for other people, using my power to

control them. I’m not going to do that anymore. Not even for someone I He paused, searching for the right word. Not even for someone I care about. That as a convenient philosophy, Thomas said bitterly. Developed after you’ve already used your power to hurt everyone around you. Yes, Marcus agreed.

It is convenient and it’s also too late. I can te undo what I’ve done. I can te bring back the people I’ve hurt. I can te erase the suffering I’ve caused. All I can do is try to be better going forward. And that starts with respecting other people s autonomy even when it scares me. Grace who had been quiet finally spoke.

Do you think she l make it back? I don’t he know Marcus said honestly. She is smart and resourceful, but she’s also taking an enormous risk. Anything could go wrong. And if she doesn’t in make it, Grace pressed, if she has captured or killed, what then? Then we grieve, Marcus said. And we continue north, and we try to build the life she was trying to build for us.

The days stretched on. They moved cautiously through the swamp, always moving north, always putting distance between themselves and the plantation. But they moved slowly, waiting, waiting for Allah to return. Waiting for news, waiting for hope. On the seventh day, just as they were beginning to lose faith, Ara emerged from the swamp.

She appeared like she never left, moving through the murky water with the same grace she always possessed. But there were signs of her ordeal. Her clothes were torn and muddy, and there was a long scratch down her arm that looked infected. Her hair was matted and her eyes had a wild quality that suggested she d been running hard.

She was carrying a small canvas bag. “I got it,” she said, holding up the bag. Her voice was breathless, but triumphant. “All of it, every penny. Enough to get us north and establish ourselves in a community of free people. Enough to start building the network I’ve been dreaming about.” How did you Samuel began but Allar cut him off. I don’t he need to explain.

She said what matters is that we have what we need. We can leave the swamp tomorrow. We can start moving toward freedom. We can start building something real. That night as they prepared to move out. As they celebrated quietly around the fire, Marcus finally understood something fundamental about that he should have understood from the beginning.

She had never needed him to save her. She had never needed his love or his protection or his sacrifice. What she had needed was his weakness, his loneliness, his desperate hunger to be seen as something other than a monster. She had needed him to be vulnerable so she could exploit that vulnerability for a greater purpose.

And she had used it perfectly. The question that haunted him as they moved north through the darkness was whether she had been right to do so. Whether the ends the freedom of these people, the potential to help others escape, the establishment of a network that could liberate hundreds or thousands justified the means of her manipulation.

He didn’t he have an answer, but he suspected. That was the point. Some questions, didn’t he have answers? Some moral questions could only be lived with, never resolved. They were the kind of questions that would follow him for the rest of his life, demanding examination, resisting easy answers, forcing him to confront the complexity of human morality.

Marcus realized that this was perhaps his real punishment, not death or capture or even exile. His real punishment was understanding finally and completely what he had done to people like understanding how his cruelty had forced her to become someone cruel in return. Understanding how his power had necessitated her cunning.

Understanding that in breaking her spirit, he had created a weapon that would eventually be turned against him. As they walked through the darkness toward an uncertain future, Marcus understood that redemption, if it was even possible, would be a long and difficult journey. It would require more than good intentions.

It would require genuine transformation. It would require him to become someone entirely different from who he had been. And he would spend the rest of his life trying to become that person, knowing that he might never fully succeed. The swamp eventually gave way to forests, and the forests gave way to rolling hills.

As they traveled north, the landscape transformed around them. Each mile putting distance between them and the plantation. Each day bringing them closer to the uncertain promise of freedom. But the physical journey was only one part of their escape. The real journey was internal, slow, painful process of learning to exist as free people in a world that still wanted to enslave them.

They traveled mostly at night, hiding during the day in barns and abandoned cabins. Marcus had money now s money taken from the plantation owner s hidden cash. They used it sparingly to purchase supplies from merchants who asked no questions. There was an underground network, Ara explained, of people who helped runaways.

Some were white abolitionists who believed slavery was a moral abomination. Others were free black people who remembered slavery or had families still trapped within it. Still others were formerly enslaved people who had escaped and now dedicated their lives to helping others do the same. The first safe house was a small farm operated by an elderly white couple named the Hendersons.

They lived in a remote area surrounded by dense forest far enough from any town that they could help runaways without drawing suspicion. The Hendersons asked no questions about who they were or where they came from. They simply provided food, shelter, and directions to the next safe house. You were not the first to come through here, Mrs.

Henderson said as she prepared a meal of beans and cornbread. And you one t be the last. As long as I am alive, this house will be a place of refuge. Why do you help us? Grace asked. She was still wary, still suspicious of white people, and her question carried an edge of challenge. Because it’s the right thing to do, Mrs. Henderson said simply.

And because my conscience one te let me do anything else. Samuel, who had been quiet, spoke up. That’s a luxury. Having a conscience that you can afford to listen to. Mrs. Henderson didn’t he argue? She simply nodded, acknowledging the truth of his words. As they moved from safe house to safe house, Marcus began to understand the scope of what Aara had been part of.

There was an entire network of people, black and white, free and formerly enslaved, working together to help people escape bondage. They had roots planned, safe houses established, and a system of communication that allowed them to coordinate efforts across multiple states. At one safe house, they met a man named Frederick, who had escaped slavery himself 15 years earlier.

He was now working with the Underground Railroad, helping to guide people north. The work is never finished, Frederick said as he showed them maps and roots. For every person we help escape, there are a hundred more still in chains. But we keep working because the alternative is to accept that slavery is inevitable, that it’s the natural order of things.

And I, one t accept that none of us will. Marcus found himself increasingly drawn into conversations about the morality of slavery, about the possibility of a world without it, about what freedom actually meant. One night, unable to sleep, he sat with Thomas by a dying fire at one of the safe houses.

“Why do you hate me so much?” Marcus asked. It wasn’t tea a confrontational question. It was genuine curiosity. Thomas was quiet for a long moment before responding. I don’t tea hate you, he said finally. Hate requires energy and I’ve learned not to waste energy on things I can tea control.

You are what you area man who participated in a system of brutality. That’s a fact. But I don’t he hate you for it. Then what do you feel? Marcus pressed. Indifference. Thomas said you re irrelevant to me now. You are just a man who happens to be traveling north with us. What you did in the past doesn’t seem matter to me anymore.

What matters is what you do now in the present. And so far, you haven’t he done anything to suggest you reworth caring about one way or another. It was a harsh assessment, but it was also, Marcus realized, more merciful than hatred would have been. Hatred would have meant Thomas cared enough to be angry.

Indifference meant Thomas had already moved past him, had already relegated him to insignificance. The journey north took three weeks. They traveled through Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana, always moving toward the communities that had been established by free black people and abolitionists. The landscape changed constantly from farmland to forests to small towns that they had to navigate carefully, avoiding the slave catchers who sometimes patrolled the roads.

There was one close call about 2 weeks into their journey. They were staying at a safe house near the Ohio border when riders came through the area searching for runaways. The family who owned the safe house see a free black family named the Johnson quickly hid Samuel Thomas and Grace in a hidden room beneath the floorboards of the cabin.

Marcus they dressed in the clothes of a free man and had him sit on the porch reading a newspaper. The slave catchers didn’t even look at him. To them, a white man sitting on a porch was invisible, unremarkable, not worth investigating. That night, after the danger had passed, Marcus understood something crucial.

His whiteness was a privilege that had allowed him to participate in brutality without consequence. And now, that same whiteness was allowing him to escape in ways that Samuel, Thomas, and Grace never could. When they finally reached their destination, a small town in Michigan where Alara had arranged for them to stay. It was almost anticlimactic.

The town was called Cass and it had been established as a community of free black people and abolitionists. There were schools, churches, businesses owned by black people. There was a sense of possibility and hope that Marcus had never experienced before. All had already arrived a few days earlier.

She was staying with a family that operated a station on the Underground Railroad, and she was already making plans for the next phase of her work. When Marcus saw her, he barely recognized her. She had cut her hair short, dyed it a different color, and she was wearing clothes that suggested a different social status. She had transformed herself again, but this time not to seduce or manipulate.

This time, she was transforming herself to survive and to work more effectively. Welcome to freedom,” she said when she saw him. Her tone was business-like, professional. “I trust your journey was uneventful. As uneventful as a journey like that can be,” Marcus replied. “You’ve done remarkable work here.

This community, the network you vivve, helped establish it s extraordinary. It s necessary,” Ara corrected. “And it’s far from complete. There are still thousands of people enslaved in the south. There are still slave catchers operating in the north. There’s still so much work to be done.

Over the following weeks, as they settled into their new lives in Cass, Marcus began to understand the true scope of Ara s vision. She was in te just helping individual people escape. She was building an infrastructure for liberation. She was training guides who could lead people through dangerous territory. She was establishing safe houses along routes that stretched from the deep south all the way to Canada.

She was coordinating with abolitionists, with free black communities, with formerly enslaved people who had escaped and now dedicated themselves to helping others do the same. And she was doing it all with the same strategic brilliance that she had once used to manipulate Marcus. Samuel and Thomas found work as carpenters, helping to build new structures in the growing community.

Grace enrolled in a school for free black children, determined to get the education that had been denied to her under slavery. Marcus found himself working with Ara, helping to coordinate the logistics of the Underground Railroad. It was ironic the man who had once been an overseer, who had once wielded power through brutality, was now using his organizational skills to help people escape the very system he had once served.

One day as they were reviewing maps and planning routes, Ara asked him a question. Do you regret it? Coming with us? I mean, leaving behind everything you had? Marcus considered the question carefully. No, he said finally. I don’t t regret it. What I had wasn’t tea worth having. It was built on suffering.

It was built on the pain of people like you. I don’t te regret leaving that behind even knowing that you will never be able to go back that you were now a fugitive yourself that there’s a price on your head especially knowing that Marcus said because it means I am finally experiencing something like what you experienced I am finally understanding what it means to live in fear to have to hide to have to constantly be aware of the danger around me it’s a small taste of what you’ve lived with your entire life and I deserve to live with that fear. I deserve to understand at least in some small way what I’ve inflicted on others. All nodded slowly. That’s good. She said that’s the beginning of real understanding. Not guilt. Guilt is self-indulgent, but understanding the recognition that you participated in a system of evil and that you can never fully atone for that

participation. All you can do is work towards something better. As the weeks turned into months, Marcus began to settle into his new life. He was no longer the overseer. He was no longer the man who wielded power through fear and brutality. He was simply Marcus, a man with a past that he couldn’t he change, working toward a future that might in some small way balance the scales of his previous cruelty.

But remained distant from him, professional and cordial, but never warm. She had moved on from their encounter, had relegated it to the past where it belonged. She was focused entirely on her work, on the mission of liberation that had always been her true purpose. One evening, as the sun was setting over the Michigan landscape, Marcus found her sitting alone on a bench outside the community center.

“I’ve been thinking about what you said,” he began. “About how you manipulated me, used me, never felt anything genuine for me.” And asked, not looking at him. I think I finally understand why, Marcus said. You couldn’t he afford to feel anything genuine. You couldn’t he afford to care about me as a person because that would have compromised your mission.

Your mission was always bigger than any individual relationship. It was always about liberation, about freedom for your people. Compared to that, my feelings are your feelings. Didn’t he matter? All turned too. Look at him then. Now you were beginning to understand. She said the personal is political.

The intimate is revolutionary. When you reighting against a system of oppression, you can te afford to be sentimental. You can te afford to put individual relationships above the collective good. But doesn’t te that cost something? Marcus asked. Doesn’t t it cost you something to live that way. to never allow yourself to feel anything genuine, to always be calculating, always be strategic. Yes, said quietly.

It costs a great deal. But the alternative is to be destroyed by the system. The alternative is to let your humanity be used against you the way it was used against you. I chose to harden myself. I chose to become a weapon and I don’t t regret that choice. She turned back to watch the sunset. You should go, she said.

There are people arriving from the south tonight. We need to prepare the safe house. You can help with that. Marcus stood, understanding that this was a dismissal and that there would be no more personal conversations between them. Aar had moved on. She had accomplished what she set out to accomplish with him.

And now he was simply another worker in her vast network of liberation. As he walked toward the safe house, Marcus realized that this was perhaps the most important lesson had taught him. That freedom wasn’t te about individual happiness or personal fulfillment. It was about justice. It was about building a world where no one had to be used.

The way had been used, where no one had to harden themselves into a weapon in order to survive. And if that meant living with loneliness with the knowledge that the one person who understood him best would never care for him well, that was a small price to pay. That was a small price to pay for the possibility of a world without slavery.

The safe house in Cass became a hub of activity as winter approached. People arrived almost daily. Families fleeing the south, individuals with nothing but the clothes on their backs, children who had never known anything but bondage. Each arrival represented a story of desperation, courage, and the human will to survive against impossible odds.

Marcus found himself working longer hours than he had ever worked at the plantation. But this work was different. This work was purposeful. This work was about building something rather than destroying it. The safe house was a large farmhouse on the outskirts of town, hidden from the main road by a dense grove of trees.

It had been converted to accommodate multiple people with hidden rooms and secret passages that had been designed by Ara herself. She had studied the architecture of similar houses along the underground railroad network, learning from the innovations of others and then improving upon them.

The kitchen was the heart of the operation. It was where people were fed, where information was shared, where the exhausted and traumatized were slowly reintegrated into the world of the Marcus found himself spending much of his time there, helping to prepare meals, listening to stories, trying to provide comfort to people who had endured unimaginable suffering.

One woman named Sarah had escaped with her two children after her husband had been sold to a plantation in Mississippi. She had walked for 3 weeks, hiding during the day, traveling at night, sustained by the hope that she might find her way to freedom. “I [clears throat] didn’t he know if we would make it,” she told Marcus as he prepared food for her and her children.

I didn’t he know if there really were places like this. Id heard stories, whispered conversations, but I wasn’t too sure if they were real or just something people told themselves to survive. “This is real,” Marcus said. All of it. The network, the people helping you, the possibility of freedom, it’s all real. But why? Sarah asked.

Why do people help us? What do they get out of it? Marcus considered the question. Some believe it’s morally right, he said. Some have religious convictions. Some have experienced slavery themselves. Some are just good people who can te accept injustice. The reasons are different for different people, but the result is the same. A help.

Sarah’s children, a boy of about eight and a girl of about six, were eating quietly, their eyes wide with wonder at the abundance of food before them. They had never known anything but scarcity, and the simple act of having enough to eat was almost incomprehensible to them. “Will we be safe here?” the boy asked, looking up from his plate.

“For now,” Marcus said. and eventually you will go to another safe house and then another until you reach Canada. In Canada, slavery is illegal. You will be safe there. How long will it take? The girl asked. Weeks, Marcus said. Maybe months, but you will make it. People have made this journey before you, and people will make it after you.

You are part of something larger than yourself. As the weeks passed, Marcus began to understand the true human cost of the system he had once served. Every person who arrived at the safe house carried trauma, physical scars from whippings, psychological scars from separation from loved ones, the deep spiritual damage that came from being treated as property rather than as a human being.

There was an old man named Jacob who had been enslaved for 60 years. He had escaped after his master died, and the new owner had planned to sell him south. Jacob was so traumatized by decades of brutality that he could barely speak. He would sit in the corner of the safe house, rocking back and forth, his eyes staring at something that only he could see.

“What happened to him?” Marcus asked one day. “Everything,” Aara said simply. “Slavery happened to him. It happened day after day for 60 years. He survived. But survival isn’t te the same as living. He l need time to heal, if healing is even possible.” Do you think he’ll ever recover? Marcus asked.

I don’t he know, said. Some people do. Some people find ways to rebuild their lives, to find joy and meaning and freedom. Others are too broken. The damage is too deep. All we can do is give them the space and support to try. It was during this period that Marcus began to understand the true nature of Ara s work.

It wasn’t te just about moving people from place to place. It was about healing, about restoration, about helping people reclaim their humanity after it had been systematically stripped away. And was remarkably skilled at this work. She had a gift for understanding what each person needed, whether it was practical help with logistics, emotional support, or simply someone to listen to their story without judgment.

But there was a cost to this work. Marcus began to notice that was becoming more and more withdrawn. She was working constantly, often late into the night, reviewing maps, coordinating with other stations on the Underground Railroad, planning routes for the next groups of people. One night, unable to sleep, Marcus found her in the office, surrounded by papers and maps. “You need to rest,” he said.

“There’s no time for rest,” Aara replied, not looking up from the map she was studying. “Every day that passes, more people are suffering under slavery. Every day that I rest is a day that someone else remains in chains. But you will burn yourself out. Marcus said you well destroy yourself in service of this cause.

Then I’ll be destroyed in service of something that matters. Ara said I’d rather burn out fighting for liberation than live a comfortable life while others suffer. Marcus wanted to argue with her. Wanted to tell her that she couldn’t te help anyone if she destroyed herself. But he understood finally and completely that arguing with Ara was feudal.

She had made her choice. She had dedicated herself entirely to the cause of liberation. And nothing he could say would change that. By early winter, the network had successfully moved over 200 people to freedom. 200 people who were no longer enslaved. 200 people who now had the possibility of building lives of their own choosing.

But there were also failures. There were people who were captured before they reached safety. There were routes that were discovered by slave catchers. There were stations that had to be abandoned because they had been compromised. One such failure came in late November. A family of five parents and three children had been captured just 20 m south of the Michigan border.

They had been spotted by a slave catcher who recognized them from wanted posters. The slave catcher had alerted authorities and the family had been apprehended and were being held in a jail awaiting transport back to the south. The news hit the community hard. Everyone at the safe house knew that there was nothing they could do.

The family was in the hands of the law now. Any attempt to rescue them would be feudal and would likely result in the capture of the rescuers as well. That night, the community gathered in the main room of the safe house, and addressed them. “We failed,” she said simply.

“We failed to get that family to safety. They will be returned to slavery and there’s nothing we can do about it. But we cannot allow this failure to paralyze us. We cannot allow it to stop us from continuing the work. Tomorrow we will review the routes and find out how the slave catchers discovered the family.

We will identify the weak points in our network and strengthen them. And we will continue to help people escape. But what about the family? Someone asked. Shouldn’t he we try to rescue them? We can tee, Allara said, her voice hard. Any attempt to rescue them would be suicide. It would result in the capture of more people and the compromise of more of our network.

We have to accept that we can te save everyone. We have to focus on saving as many people as we can. It was a brutal calculus, but it was also Marcus realized the only way to operate when you were fighting against a system as powerful and entrenched as slavery. As winter deepened, the work continued. The safe house became a place of constant activity.

People arriving, people departing, people healing from the trauma of their escape. The community that had formed around the work of liberation became tighter, more committed, more willing to sacrifice for the cause. Samuel and Thomas had become integral to the operation. They were using their skills as carpenters to build and maintain the hidden rooms and passages that were essential to the safe house s function.

Grace had become an assistant teacher at the school for free black children, and she was using her own experience of slavery to help other children understand that freedom was possible. And Marcus continued his work in the kitchen and in coordinating logistics, slowly becoming less of an outsider and more of a genuine member of the community.

But there was always a distance between him and Aara. She treated him with professional courtesy, but there was no warmth, no personal connection. She had moved on from their encounter completely, had relegated it to the past where it belonged. One day in early December, as Marcus was helping to prepare the safe house for the arrival of a new group of refugees, Aara pulled him aside.

“I’m leaving,” she said. The words hit Marcus like a physical blow. What do you mean? He asked. I mean, I am leaving Cass, Ara explained. IV established this station and IV trained people to run it. It’s functioning well now, but there’s more work to be done. There are other communities that need to be established, other routes that need to be developed.

I’m going to move on. Where? Marcus asked. South, Aara said. I’m going to go back to the south and work from within. I’m going to help organize escapes from the inside the way I did at the plantation. I’m going to build a network of people who are willing to help others. Escape? That is incredibly dangerous, Marcus said.

If you re caught, if I am caught, I will be executed. All said matterofactly. But I won to be caught. I am too good at what I do. I can blend in, disappear, become invisible. I can do more good working from within the south than I can do here in the north. When are you leaving? Marcus asked. Tomorrow, Aara said.

I arranged for a guide to take me south. I’ll be traveling in disguise, posing as a free woman of color looking for work. I ll make my way to Louisiana where I have contacts who can help me establish the network. Marcus wanted to beg her not to go. He wanted to tell her that she was too valuable to risk, that the work she was doing in Cass was important, that she didn’t he need to put herself in such danger.

But he didn’t he say any of those things. He had learned finally that Allara s choices were her own to make. He had no right to try to control her or influence her decisions. “I’ll help you prepare,” he said instead. That night, they worked together to pack supplies and prepare for her departure.

They didn’t te speak much. There wasn’t tea much to say. Everything that needed to be said between them had already been said. As dawn broke, Ara prepared to leave. She was dressed in the clothes of a free woman of color simple dress, a bonnet, nothing that would draw attention. She carried papers that identified her as a free person, papers that had been forged by an expert in the community.

“Take care of the people here,” she said to Marcus as she prepared to mount the horse that would carry herself. “Help them heal. Help them build new lives. That’s the real work of liberation. Not just helping people escape but helping them become whole again. I will Marcus promised and Marcus Allar added dant tried to follow me.

Dant tried to find me. Dant tried to contact me. This is where our paths diverge. You have your work to do here and I have mine in the south. We one team meet again. I understand. Marcus said and he did understand. He understood that Ara had never been his. She had been a tool that he had tried to use, and she had turned that tool against him.

And now she was moving on to the next phase of her work, leaving him behind. As he watched her ride away into the morning mist, Marcus felt something shift inside him. It wasn’t tea quite grief, though there was an element of that. It was more a sense of finality, of closure, of the end of a chapter in his life.

He had come to the north seeking redemption. He had thought that by helping others escape slavery, he could somehow balance the scales of his previous cruelty. But he was beginning to understand that redemption wasn’t te something you could achieve. It was something you worked toward every day for the rest of your life, knowing that you might never actually achieve it.

And perhaps that was the point. Perhaps the work itself was the redemption, not the achievement of it. As Marcus turned back toward the safe house, he saw Samuel standing in the doorway, watching him with an expression of understanding. “She’s gone,” Samuel said. “It wasn’t he a question?” “Yes,” Marcus confirmed.

“She’s gone back to the south. She’s going to continue the work from there.” Samuel nodded slowly. “She’s remarkable,” he said. dangerous and remarkable. The kind of person who changes history. Yes, Marcus agreed. She is. And you let her go, Samuel said. Even though you could have tried to stop her.

I had no right to stop her. Marcus said her life is her own. Her choices are her own. All I can do is respect that, even if it means losing her. Samuel studied him for a moment and then nodded as if he had come to some conclusion about Marcus s character. Come on, Samuel said. There’s work to be done.

A new group is arriving this evening, and we need to prepare the safe house. As Marcus followed Samuel back into the house, he understood that this was his life now. This was his purpose. Not seeking redemption for his past, but working toward justice in the present. Not trying to reclaim Aara or win her affection, but honoring her by continuing the work she had started.

The work of liberation, the work of freedom. The work that would continue long after all of them were gone, carried forward by others who would take up the cause. And perhaps that was the greatest legacy anyone could lean on their own redemption.