May 5th, 1945.

0720 hours.

Wageningan, Western Netherlands.

Staff Sergeant William Cooper of the 101st Airborne Division stood at the edge of the small Dutch town, watching civilians emerge from their homes as American forces rolled through the streets.

He’d seen liberated populations before, France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and expected the usual celebrations, flags waving, people cheering, perhaps some wine and kisses from grateful locals.

What he saw instead stopped him cold.

The people moving slowly toward the American convoy weren’t celebrating.

They were shuffling.

elderly moving like they were ancient adults supporting each other and children who looked more like ghosts than human beings.

A little girl, maybe 7 years old, stood by the roadside in a dress that had been altered multiple times to fit her shrinking frame.

Her face was skeletal, her eyes enormous in hollowed sockets, her legs like sticks in wooden clogs that were probably the only shoes she owned.

When Cooper’s Jeep stopped, the girl took a tentative step forward, staring at the Americans with an expression that mixed desperate hope with the caution of someone who’d learned not to expect kindness.

She didn’t wave or smile.

She just stood there, swaying slightly, too weak for anything more energetic than standing.

Cooper reached into his pack and pulled out a d-ration chocolate bar.

He knelt down and extended it toward the girl who stared at it without moving.

For a moment, he thought she didn’t recognize what it was.

Then her hand shot out, grabbed the chocolate, and clutched it to her chest like it was the most precious thing in the world.

Tears began streaming down her hollow cheeks.

“Thank you,” she whispered in English, her voice barely audible.

“Thank you.

Thank you.

Thank you.

Behind her, more children were appearing.

20, 30, 40 of them, all skeletal, all staring at the Americans with that same mixture of hope and disbelief.

Cooper looked at his men, saw the shock on their faces as they registered what months of starvation had done to an entire population of children.

Break out all the rations, Hooper ordered quietly.

everything we’ve got.

These kids are starving to death.

What followed was chaos of the best kind.

American soldiers distributing every scrap of food they carried.

Children crying as they held chocolate and crackers and canned meat.

Dutch parents collapsing to their knees in gratitude.

And hardened combat veterans discovering that feeding starving children felt more meaningful than any battle they’d won.

For the Dutch civilians of Western Netherlands who’d survived the hunger winter of 1944 45, American liberation meant more than military victory or political freedom.

It meant food for children who’d been dying of starvation.

It meant the end of watching your own sons and daughters waste away while you were powerless to save them.

It meant the moment when hope which had died slowly over months of systematic deprivation suddenly miraculously returned.

The deliberate starvation.

The hunger winter that devastated western Netherlands from September 1944 through May 1945 was neither natural disaster nor unfortunate consequence of warfare.

It was deliberate German policy designed to punish Dutch civilians for supporting Allied operations and to maximize suffering during occupation’s final months.

The numbers documented systematic atrocity.

Dutch civilians in Western Netherlands affected approximately 4.5 million.

Deaths directly attributable to starvation 18,000 22,000.

Children who died estimated 2500 3,000.

Children showing severe malnutrition symptoms at liberation, approximately 200,000.

Daily caloric intake by February 1945, 400 800 calories per person.

Food distribution ceased entirely, multiple weeks in early 1945.

Fuel available for heating, essentially none by January 1945.

The crisis began in September 1944 when the Dutch government in exile called for a railway strike to support Allied operations following the failed market garden offensive.

German authorities retaliated by imposing food embargo on western Netherlands, cutting off supplies to the most densely populated region of the country.

The timing was catastrophic.

The embargo began just as winter approached when stored food from harvest would normally sustain populations through cold months.

With railway system paralyzed and German forces blocking road transport, Western Netherlands became isolated food desert where existing stocks were consumed within weeks and no resupply was possible.

German occupation authorities demonstrated systematic indifference to Dutch civilian suffering.

Requests for food relief were ignored or denied.

Appeals to international humanitarian organizations were blocked.

The deliberate policy was clearly articulated in German military communications.

Dutch support for Allied operations would be punished through deprivation that would create object lesson about costs of resistance.

the descent into hunger.

The progression of starvation followed predictable patterns that Dutch civilians documented in diaries, letters, and testimonies that survived the war.

The decline from adequacy to crisis to catastrophe happened gradually.

Then suddenly, as each threshold of desperation was crossed, September October 1944, rationing tightened, but remained minimally adequate.

Families consumed stored food, hoped embargo would end quickly, maintained relative normaly despite shortages.

November December 1944, rations dropped below subsistence levels.

Families began consuming everything.

Furniture burned for fuel.

Gardens stripped of anything edible.

Pets killed for meat.

First starvation deaths reported, primarily elderly and infirm.

January March 1945, full catastrophe.

Ration distribution became sporadic, then ceased entirely for weeks at a time.

Families boiled tulip bulbs, which were toxic but provided minimal calories.

Sugar beats, normally livestock feed, became precious food.

Deaths accelerated dramatically.

April 1945, peak suffering.

With spring approaching but no food reserves surviving winter, death rates reached their highest.

Parents watched children waste away, unable to provide even minimal nutrition.

Mass graves were dug for starvation victims.

Entire communities hovered at edge of collapse.

The psychological impact of watching children starve was documented in countless testimonies.

Parents described the agony of having nothing to feed hungry children, of watching them grow weaker daily, of making impossible choices about dividing inadequate food among multiple children.

The despair was absolute.

Knowing your children were dying and being powerless to save them.

Anna Vandenberg, a mother of three in Amsterdam, wrote in her diary in March 1945, “Today, my youngest asked for bread.

I had none.

She cried, then stopped crying because she’s too weak to cry for long.

She’s 7 years old and weighs perhaps 30 lb.

I watch her dying and can do nothing.

If Americans don’t come soon, she won’t survive.

None of them will.

I pray to God for food, but God seems as far away as the Americans.

The children’s suffering.

Children bore the heaviest burden of hunger winter because growing bodies required nutrition that simply wasn’t available.

The physiological effects of severe childhood malnutrition were documented by Dutch doctors who maintained medical records despite impossible conditions.

The symptoms followed predictable progression.

Initial weight loss, then muscle wasting, then edema from protein deficiency, then organ system failures that preceded death.

Children’s bodies cannibalized their own tissues to sustain basic functions.

Their immune systems collapsed, making them vulnerable to diseases that would be minor under normal circumstances.

Schools that remained nominally open became showcases of horror.

Teachers reported children fainting from hunger during lessons.

Some children were too weak to walk to school.

Others fell asleep at desks because conserving energy had become more important than education.

The few teachers who still had food would share tiny portions with students who looked closest to death.

Dr.

Henrik Moulder, a pediatrician in Rotterdam who treated starving children throughout the crisis, documented the medical reality.

By March 1945, I was seeing children in conditions I’d only read about in medical texts on famine, quashior, morasmus, severe vitamin deficiencies causing blindness and bone deformities.

Children aged 10 who weighed what healthy 5-year-olds should weigh.

Some were past the point where food could save them.

Their organs had been too damaged by months of starvation.

All I could do was make them comfortable while they died.

The psychological effects on children were equally devastating.

Chronic hunger consumed their consciousness.

They became listless, withdrawn, unable to play or engage in normal childhood activities.

Some became obsessed with food.

Talking constantly about meals they remembered from before the embargo.

Others stopped talking about food because discussing what they couldn’t have was too painful.

The Allied dilemma.

Allied forces advancing through Europe in early 1945 faced strategic priorities that delayed liberation of Western Netherlands.

The region wasn’t directly on the path to Germany.

German forces there weren’t posing significant military threat.

Diverting resources to liberate Western Netherlands would slow the advance into Germany proper and potentially prolong the war.

But Allied commanders were aware of the humanitarian crisis developing behind German lines.

Intelligence reports, communications from Dutch resistance, and information from refugees described the starvation conditions.

The strategic calculus became deeply uncomfortable.

Pursue fastest military victory while Dutch civilians starved or divert resources to humanitarian relief while the war continued.

The initial decision was to prioritize military advance.

Western Netherlands would be liberated as part of final operations after Germany’s defeat.

In the meantime, Allied forces attempted to provide some relief through airdrops of food supplies to starving regions.

Operation Mana by the RAF and Operation Chow Hound by the USAF.

The airdrops began in late April 1945 after negotiations with German commanders who agreed not to fire on Allied aircraft flying humanitarian missions.

British and American bombers that had carried death to German cities now carried food to Dutch civilians, dropping supplies over designated zones where starving populations could retrieve them.

The airdrops provided crucial relief, but couldn’t solve the crisis.

Supplies reached only fraction of affected population.

Distribution was chaotic and most critically children who were already dying of starvation needed immediate sustained nutrition that occasional airdrops couldn’t provide.

Full liberation and systematic food relief remained necessary.

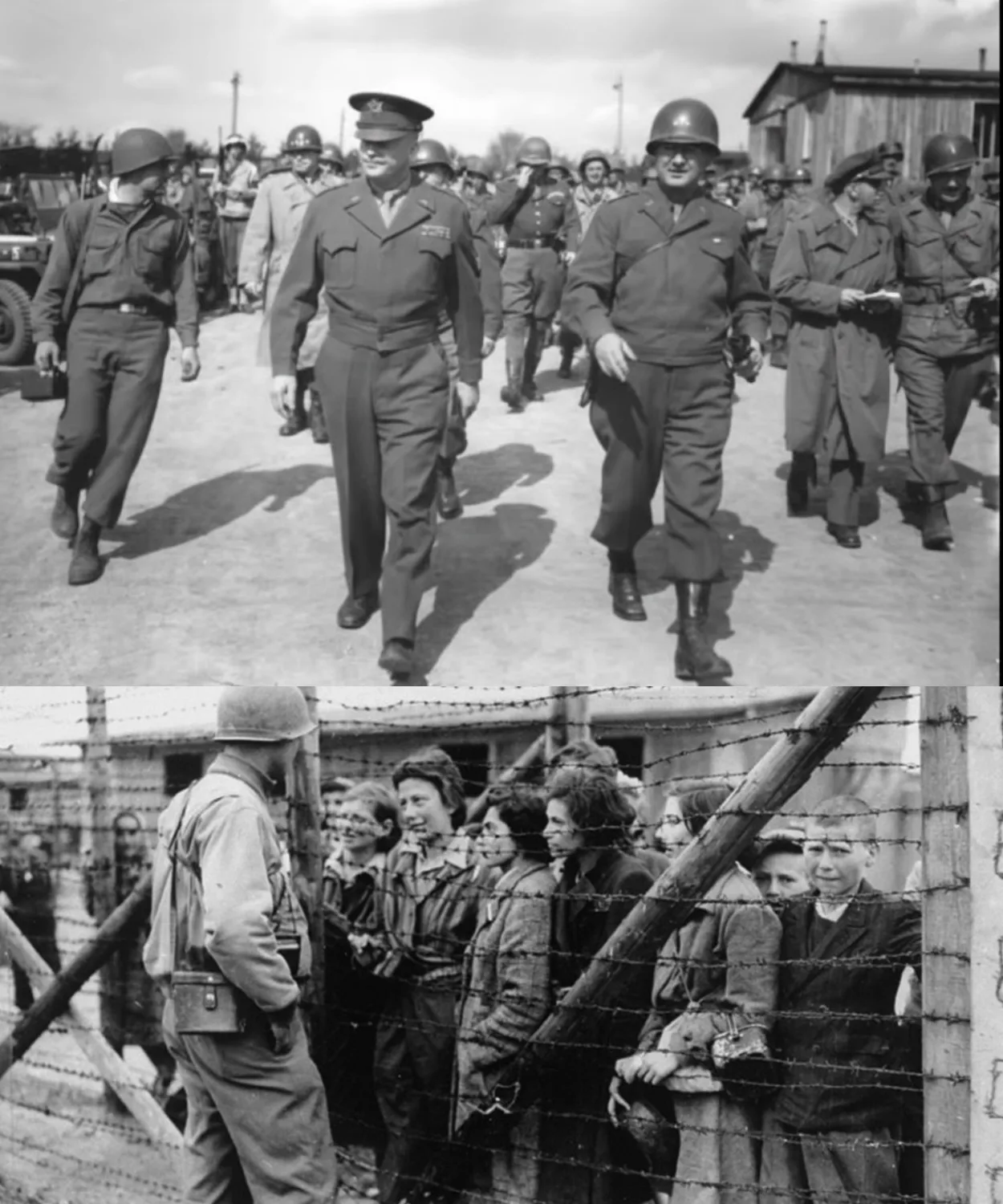

The ground liberation.

When Allied ground forces finally liberated Western Netherlands in early May 1945, simultaneously with German surrender, they discovered humanitarian crisis that exceeded anything intelligence reports had fully conveyed.

The statistics had documented deaths and malnutrition.

They hadn’t captured the visceral reality of entire communities on the edge of collapse.

American and Canadian forces advancing into Western Netherlands encountered populations that were simultaneously desperate for liberation and too weak to properly celebrate it.

The traditional scenes of joyous liberation, dancing in streets, cheering crowds, flowers thrown at soldiers were replaced by more subdued but profoundly emotional responses from people who’d been starved for months.

Captain Thomas Morrison, whose company was among the first American units into Vaganingan, described the scene.

We expected celebrations.

We got something more moving and more heartbreaking.

People came out of their homes slowly, carefully, like they weren’t sure they had energy to spare on celebration.

When they saw we had food, that we were distributing it immediately, many just broke down crying.

Grown men weeping, women collapsing to their knees in gratitude, children staring at chocolate bars like they’d forgotten such things existed.

It was the most emotional liberation I’d experienced in the entire war.

The immediate priority became feeding starving populations as quickly as possible.

Combat units that had been focused on military objectives suddenly found themselves running humanitarian operations on massive scale.

Every available food supply was broken out and distributed.

Field kitchens prepared meals continuously.

Medical personnel triaged the most severely malnourished for urgent treatment.

The American response.

American soldiers who participated in feeding operations in the Netherlands experienced the work as among the most meaningful of their entire military service.

They’d fought across Europe, won battles, defeated German forces.

But feeding Dutch children who were starving to death felt more significant than any combat victory.

The soldiers response went beyond following orders or completing assigned missions.

They gave away personal supplies, shared their own rations, spent offduty time playing with Dutch children and helping families.

The humanitarian work became personal investment in helping people they’d come to care about.

Private First Class Eugene Henderson wrote to his family in Massachusetts in May 1945.

We’re feeding Dutch families who haven’t had real food in months.

The children cry when you give them chocolate, not because they’re sad, but because they’re so grateful they can’t contain the emotion.

Yesterday, a little girl gave me a flower she’d picked.

It was the only thing she had to give, and she wanted me to have it because I’d given her food.

I cried.

I’m not ashamed to admit it.

This is why we fought the war, so children like her could have flowers instead of starvation.

The cultural connections formed between American soldiers and Dutch civilians were immediate and deep.

The Netherlands was Western European nation with cultural similarities to America, democratic traditions, and populations that spoke some English.

The connection was easier and more natural than in some other liberated territories.

Dutch families opened their homes to American soldiers, sharing what little they had recovered.

Americans responded with food, supplies, and friendship.

Children followed American soldiers everywhere, practicing English, asking about America, showing them around recovered towns.

The relationships transcended military occupation to become genuine cross-cultural friendships.

The children’s recovery, the physical recovery of Dutch children from severe malnutrition required months of careful nutrition and medical care.

Bodies that had been systematically starved couldn’t simply resume normal function when food became available.

The rehabilitation process was gradual, supervised, and often complicated by medical issues resulting from prolonged deprivation.

American and allied medical personnel established specialized clinics for treating childhood malnutrition.

The facilities provided supervised feeding, vitamin supplementation, treatment for diseases that had flourished during starvation periods, and monitoring for complications.

The care was comprehensive and represented significant commitment of medical resources to civilian population.

The psychological recovery was equally important and equally complex.

Children who’d spent months or years living with chronic hunger.

Watching people die of starvation and experiencing the terror of not knowing if they’d survive needed more than just food.

They needed safety, stability, and time to process trauma.

Allied personnel organized schools, recreation programs, and activities designed to help Dutch children begin recovering normal childhood experiences.

American soldiers played baseball with Dutch kids, taught them American songs, organized games and events.

The activities were more than entertainment.

They were psychological rehabilitation through normal childhood experiences.

The closing truth.

The story of Dutch civilians breaking down when American soldiers saved their children was never primarily about military strategy or political liberation.

It was about the most basic human obligation, feeding hungry children, and what happens when nations with resources choose to use those resources for humanitarian purposes rather than exclusively military objectives.

The American soldiers who broke out their rations and fed starving Dutch children weren’t following orders or completing missions.

Most were violating regulations about conserving military supplies.

They were making moral choices to prioritize human suffering over logistical efficiency.

Deciding that feeding dying children mattered more than maintaining supply reserves for combat units.

The Dutch civilians who broke down crying when Americans arrived with food weren’t celebrating political liberation or military victory.

They were experiencing the overwhelming relief of parents who’d watched their children dying of starvation.

and suddenly miraculously had food to give them.

The tears were about life and death at the most fundamental level.

Children who would live instead of die because strangers with resources chose to share them.

The liberation of the Netherlands demonstrated that victory could mean more than defeating armies.

It could mean saving children from starvation.

It could mean demonstrating that democratic societies valued human life enough to mobilize massive resources for humanitarian purposes.

It could mean creating bonds between nations that would last generations because one nation remembered that another nation had saved its children when they were dying.

For the Dutch children who survived hunger winter because American soldiers gave them food, the experience shaped their entire understanding of what America represented.

They grew up knowing that Americans had saved them, that democratic societies could be both militarily powerful and deeply compassionate, that enemies could become liberators who cared whether children lived or died.

And for American soldiers who participated in feeding operations, the experience provided meaning that transcended military service.

They’d helped win a war, but more importantly, they’d saved children’s lives.

They’d been part of something that demonstrated humanity’s capacity for compassion, even amid total wars brutality.

The skeletal children in wooden clogs who’d stared at chocolate bars like they were miracles.

who’d cried because strangers were kind to them, who’d experienced hope returning after months of despair.

They lived.

They grew up healthy.

They raised their own children in prosperity and peace.

They became living evidence that mercy could triumph over systematic cruelty, that civilization could choose to feed the hungry rather than ignore their suffering, and that even in war’s darkest moments, individuals who chose compassion could change the world one chocolate bar, one can of rations, one moment of kindness at a Five.