The American doctor’s hands were inside her body and Dr.

Ko Tanaka realized with horror that she was still conscious.

Blood pulsed against his fingers in rhythmic waves.

Thump, thump, thump.

Each beat weaker than the last.

Each one counting down to an ending she had accepted 18 hours ago when the transport plane went down in the Texas desert.

Above her surgical lights burned white hot, blurring into halos that merged with the pain radiating from her abdomen.

The smell hit her next.

Antiseptic, sharp and chemical, so different from the smell of burning metal and her own blood that had filled her nostrils for 3 days while she lay buried in wreckage waiting to die.

American voices shouted medical terms she recognized from her training at UC San Francisco 7 years ago.

When the world was different, when she believed medicine could transcend borders, when she was young and foolish enough to think an oath meant something more than words on paper.

Her vision sharpened for a moment.

She saw the American flag hanging on the concrete wall behind the surgical theater.

Red, white, and blue.

The enemy’s colors, the colors of the men who had dropped atomic fire on her homeland, on her family, on everything she had ever loved.

Why were they operating on her? Why hadn’t they let her die in that Texas dust where enemy soldiers belonged? The pain flared again, white hot in total, dragging her back under consciousness like an anchor, pulling a ship to the ocean floor.

In that descent, memories surfaced.

Not the memories she wanted, not the good ones.

The memories that haunted her in the dark moments between waking and sleep.

18 hours earlier, August 14th, 1945, in the morning, when the summer sun was already punishing the earth below.

The transport plane carrying her from Crystal City internment camp back to California had been old, unreliable, held together by welds and prayers and the desperate hope that the war would end before it killed anyone else.

She remembered the moment the engine coughed, a sound like a man drowning, then silence, then the screaming of metal tearing itself apart as they dropped from the sky like a stone.

The impact came hard and fast and wrong.

Her body thrown against restraints.

Her medical kit flying from her hands.

The sound of breaking bones.

Not hers.

The pilots.

Then fire.

Smoke.

The smell of aviation fuel burning.

She had crawled through wreckage.

Her abdomen screaming in protest, feeling the wetness spread across her uniform.

Blood.

Her blood.

Shrapnel lodged somewhere deep inside where her hands could not reach.

where only another surgeon’s skill could save her.

But she was the enemy, and enemies did not deserve saving.

For three days, she lay in the rubble of the crash plane two miles from anywhere buried under twisted metal in the merciless August heat of West Texas.

The sun beat down like a punishment, like divine retribution for wearing the uniform of the Imperial Japanese Army.

For serving the regime that had brought war to the Pacific, for standing by while atrocities were committed in the name of empire and honor, and all the lies that men tell themselves when they want to justify cruelty, her hand found the metal medical box, even as consciousness slipped away.

Waterproof, battered, but intact.

Inside it, wrapped in oil cloth, lay a journal.

237 names.

237 Allied prisoners she had treated in secret at Crystal City.

Men she had saved when her commanders ordered her to let them die.

Men whose families thought they were lost forever.

Men whose locations she had documented with meticulous precision so that someone someday might bring them home.

If the Americans found this journal, they would know what she had done.

They would know she had betrayed her own command to honor her oath.

They would know she had risked execution to save enemy soldiers because she believed foolishly that the hypocratic oath meant something.

That medicine transcended nationality, that her hands were meant to heal, not harm.

But if they found the journal, would they believe it? Or would they see only another enemy trick another deception from the nation that had attacked Pearl Harbor, that had committed the atrocities at Baton, that had tortured prisoners of war with casual cruelty she did not know.

And in that moment, buried in wreckage with shrapnel tearing her apart from the inside, she thought.

Perhaps it did not matter.

Perhaps justice meant dying here in the Texas desert, anonymous and alone.

Her good deeds buried with her body.

That would be fitting, she thought.

That would be right.

But then the voices came.

American voices.

Soldiers, young men speaking English with accents that reminded her of her medical school classmates.

Hands reaching into the wreckage.

Strong hands, careful hands, lifting debris away, finding her.

Seeing her uniform, the Imperial Japanese Army insignia, the Medical Corps designation, she waited for the hands to stop, waited for them to leave her there, waited for the justice she deserved.

Instead, they lifted her free, carried her to a jeep, drove her through desert heat toward Fort Bliss Army Hospital while she bled into their seats, and wondered what kind of men saved their enemies.

The present crashed back into focus.

The surgical theater, the American doctor’s hands still moving inside her abdomen with careful precision.

A woman’s voice tight with controlled anger.

She’s coding.

Blood pressure 60 over 40 and dropping.

The kerosene lamps flickered despite the electric lights overhead.

A backup system perhaps.

Everything in wartime was backup systems and desperate measures and making do with what remained.

Rain hammered against the corrugated tin roof of the converted aircraft hanger with such violence that the sound drowned out Ko’s heartbeat in her own ears.

She could barely hear her thoughts, but she heard the voice from somewhere near the doorway.

Male, tired, resigned.

She won’t survive the night.

The American surgeon did not look up.

Did not acknowledge the speaker.

His eyes stayed fixed on her face, watching the color drain from her skin like water from a broken vessel.

Every instinct must have screamed at him to walk away.

Ko thought she knew that struggle.

She had faced it a hundred times at Crystal City.

Every time she snuck into the prisoner section after dark, every time she dug shrapnel from an American soldier’s shoulder, every time she gave her own food rations to men who wore the uniform of her enemy, but his hands remained pressed against her abdomen, feeling the pulse of her failing life beneath his palms.

He was perhaps 38, 40 years old, sandy hair going gray at the temples, lines around his eyes that spoke of too many surgeries, too many young men dying on tables just like this one.

He wore the insignia of an army captain.

His name tag read Hayes.

Dr.

Daniel Hayes.

She tried to remember if she had heard that name before.

Tried to place it in the fog of her memory, but the pain made thinking impossible.

His jaw clenched so hard she could see the muscles jumping beneath his skin.

Then he spoke and his words sounded like they came from someone else.

Someone who still believed in oaths and honor and the idea that mercy meant something.

Then we have until morning prep or get me four units of O negative.

All the gauze we have left and someone find me an anesthesiologist who hasn’t been drinking.

He paused, the silence stretched.

Then he added his voice hardening into steel.

I’m not letting her die to my watch.

The silence that followed was broken only by the rain and the distant rumble of artillery from the training ranges.

Or perhaps it was thunder.

In Texas in August, the two sounds were often indistinguishable.

The nurse stared at him like he had lost his mind.

Somewhere in the doorway, a corman took a step back.

And in the darkness outside, a soldier laughed, bitter, disbelieving.

The sound of a man watching his commander make a decision that would cost them all something precious.

Ko closed her eyes.

She wanted to tell him to stop.

Wanted to tell him to save his supplies for American boys who deserve them.

wanted to tell him that she understood hatred, that she carried it herself, that mercy was a luxury neither of them could afford in a world that had just dropped atomic bombs on cities full of civilians.

But the anesthesia pulled her under before she could form the words, for she could release him from the burden of saving her life.

The last thing she heard was the sound of surgical instruments being laid out on steel trays.

The click and scrape of metal on metal.

The sound of preparation.

The sound of a man choosing to honor his oath even when everything argued against it.

Then darkness took her.

And in that darkness she dreamed.

She dreamed of San Francisco.

1938.

A different world.

A world where war was still something that happened to other people in distant countries.

She had been 24 years old, the only woman in a medical school class of 47 men, the only Japanese student in a program that prided itself on diversity while practicing exclusion in a thousand subtle ways.

Her anatomy professor, Dr.

William Harrison, had called her to his office after the first examination.

She remembered standing in front of his desk, handsfolded, waiting for the criticism she knew was coming, waiting for him to tell her that perhaps medicine was not the right path for a woman, for a foreigner, for someone who would never truly belong in American hospitals.

Instead, he had smiled, a genuine smile that reached his eyes.

Miss Tanaka, he had said, “You scored the highest in the class, 96%.

Exceptional work.” She had not known what to say.

Thank you seemed inadequate.

Dr.

Harrison had leaned back in his chair regarding her with an expression she could not quite read.

Then he spoke words that would echo through her life like a bell tolling across water.

Medicine transcends borders, Miss Tanaka.

Your oath is to humanity, not to nations.

Remember that when the world tries to make you choose between your heritage and your calling, remember that healing knows no flag, no allegiance, no boundary except the one between life and death.

We are physicians first.

Everything else is secondary.

She had believed him then.

Believed it with the fierce certainty of youth.

Believed it through graduation in 1939.

Believed it when she returned to Japan to serve her country as a military surgeon.

believed it even as war clouds gathered and the politicians spoke of destiny and empire and all the pretty words that disguise the ugly truth of conquest.

She believed it still at Crystal City in 1943 when she was assigned to treat Japanese American interneees held by the United States government.

The irony was not lost on her.

a Japanese military surgeon sent to care for American civilians of Japanese descent imprisoned by their own country for the crime of their ancestry.

The camp set in South Texas, not far from the Mexican border.

Harsh land, unforgiving, the summer heat could kill.

The winter cold could do the same.

But Crystal City held more than just internes.

In a separate section behind additional fences and guard towers, Allied prisoners of war were kept.

men captured in the Pacific theater, Americans, British, Australians, Filipinos, all of them held in conditions that violated the Geneva Convention they were supposedly protected by.

The camp commander, a man whose name she had tried to forget but never could, had made his position clear on her first day.

You treat our people, you do not treat theirs.

They are enemy combatants.

They receive minimal care, just enough to keep them alive for labor details.

Nothing more,” she had nodded.

Agreed.

What else could she know but that night, unable to sleep in the suffocating heat of her quarters, she heard the sounds from the prisoner section, moaning, crying, the sound of men dying slowly from infected wounds because no one would waste medicine on enemies.

She remembered standing at the fence, separating the sections, looking across at the dark barracks where Allied prisoners lay suffering.

Remembered the weight of her medical kit in her hands.

remembered thinking about Dr.

Harrison’s words.

Medicine transcends borders.

The first time she crossed that line, she thought she would be caught immediately.

Thought the guards would shoot her.

Thought she would die for the crime of showing mercy to enemies.

Instead, she found a young Marine from Virginia, 22 years old, gunshot wound to the left shoulder, 3 weeks old, infected beyond recognition.

The tissue had gone black with gang green.

Without intervention, he would lose the arm.

probably lose his life.

His name was John Mitchell.

She operated on him by candle light in a storage shed using instruments she had smuggled from the medical building using techniques she had learned at UC San Francisco under professors who taught her that all patients deserve the same quality of care regardless of who they were or where they came from.

John Mitchell had been delirious with fever and infection.

But as she worked digging out the bullet fragments, debriding the dead tissue, cleaning the wound with precious antiseptic, he had opened his eyes, met her gaze, seen her Japanese features, her military uniform.

Why? He whispered, “Why help me?” Because she had answered in broken English because hypocratic oath.

Same for all.

She saved his life that night.

Then she saved another and another, 237 in total over two years, operating in secret, hiding from guards, giving her own food rations to help men heal faster.

Documenting everything in a leather journal she kept hidden in her medical kit.

Names, service numbers, injuries, treatments, transfer locations.

She documented because she knew that many of these men were listed as missing in action.

Their families thought them dead.

But if someone found this record, if someone who cared about bringing men home found this list, they could use it.

They could reunite families.

They could bring a closure to mothers and wives and children who waited in agony for news that never came.

It was a fool’s hope, a desperate gamble.

But it was all she could offer.

The gamble almost killed her.

The guards caught her eventually.

Not in the act, but close enough.

They found antiseptic missing.

found surgical instruments that should have been in the medical building hidden in her quarters.

The camp commander had her beaten publicly in front of both the internees and the prisoners, a warning to anyone else who might think about showing mercy to enemies.

Then he transferred her, sent her back to California for reassignment, punishment disguised as standard rotation.

She would have been sent to Japan to the front lines to field hospitals where surgeons died alongside soldiers.

But the war was ending.

Everyone knew it, even if no one said it out loud.

The atomic bombs had fallen.

Hiroshima on August 6th.

Nagasaki on August 9th.

Her family had lived in Hiroshima.

Past tense had lived.

The telegram came 3 days after Nagasaki.

Brief clinical.

Every word a knife.

Tanaka family.

Hiroshima.

Deceased.

All members.

Atomic blast.

August 6th, her father, her mother, her two younger brothers, everyone she had loved, everyone who mattered, gone, vaporized in an instant by a weapon that made conventional warfare look merciful by comparison.

She had not cried when she read the telegram, had not screamed or raged or broken down.

She had simply folded the paper carefully, placed it in her medical kit next to the journal of names, and continued her duties.

What else was there to do? grief was a luxury she could not afford.

Not while men were still dying.

Not while her hands could still save lives.

The transport plane was supposed to take her to San Francisco.

From there, she would have been repatriated to Japan, to a country that no longer existed as she had known it, to cities reduced to ash, to a culture shattered by total defeat.

Instead, the plane crashed and she ended up here on an American operating table under the hands of an American surgeon who chose to save her life despite every reason to let her die.

The dream shifted, became darker, became the fever dream of a woman hovering between life and death.

While a surgeon fought to keep her in the world, she saw her father’s face.

kind, gentle, a professor of literature who had never understood why his daughter wanted to be a doctor instead of a teacher or a wife.

But he had supported her anyway, paid for her education in America, told her to be proud of what she accomplished.

She saw her mother, small, fierce, the kind of woman who could run a household with military precision while maintaining the grace and elegance expected of her station.

She had taught KO tea ceremony, calligraphy, all the traditional arts that were supposed to define a proper Japanese woman.

But she had also taught her daughter to be strong, to stand up for what she believed, to never let anyone tell her she was less than equal.

She saw her brothers, twins, 16 years old when the bomb fell, still children, really, still believing the propaganda about honor and sacrifice in the divine destiny of the empire.

They had wanted to be soldiers, had romanticized war the way boys do when they have never seen what bullets do to human bodies.

Now they would never grow old enough to learn that lesson, would never experience disillusionment, would never come home from war carrying scars.

is both visible and invisible.

They were simply gone as though they had never existed.

Ko’s dreaming mind tried to reach for them, tried to apologize for not being there, for being in America when her family needed her most.

For choosing medicine over duty to her parents, for all the ways she had failed them.

But they were beyond her reach now, beyond anyone’s reach.

And all she could do was continue, continue healing, continue fighting for the idea that life mattered more than nationality.

That mercy transcended politics.

That her oath meant something.

Even in a world gone mad with hatred, the dream faded.

Consciousness returned in fragments.

Pain, beeping monitors, voices speaking in controlled urgency.

She tried to open her eyes.

Failed.

Tried again.

Succeeded partially.

Blurred shapes resolved into people.

The American surgeon, the angry nurse, a young soldier who looked barely old enough to shave.

Others she could not identify.

All of them moving with the practice choreography of a surgical team working in sink.

How long had she been under days? She had no way to know.

The surgeon’s voice cut through the fog.

Vitals.

A male voice responded.

Older, weathered by experience.

Blood pressure 92 over 58, heart rate 108.

She’s stabilizing against every law of medicine and common sense.

Daniel, she’s actually stabilizing.

The surgeon called Daniel Hayes stepped back from the table.

His surgical gown was soaked with blood.

Her blood.

His face showed exhaustion beyond measure, but his eyes showed something else.

Something that looked almost like hope.

Then she’s going to live, he said quietly.

Against all odds, against all expectations, she’s going to survive.

And in that moment, hearing those words spoken by an enemy who had become her unlikely savior, Dr.

Ko Tanaka understood something profound.

Understood why Dr.

Harrison had been right all those years ago.

Understood why she had risked everything to save 237 allied prisoners.

understood why the oath mattered more than flags or nations or all the artificial divisions humans created to justify cruelty to each other.

Medicine transcended borders.

Mercy transcended hatred.

And sometimes in the darkest moments of human history, a single decision to choose compassion over vengeance could change everything.

She closed her eyes again, not from pain this time, from something else.

something that felt dangerously close to gratitude, to wonder, to the recognition that the world might be more complicated than propaganda allowed, that enemies might be capable of mercy, that the Americans she had been taught to hate might be capable of seeing past her uniform to the human being beneath.

The anesthesia pulled her under once more, but this time she did not dream of loss.

She dreamed of possibility, of a future she had not allowed herself to imagine, of a world where her hands could continue healing, where the journal of names might actually bring soldiers home, where mercy might prove stronger than hatred.

After all, outside the surgical theater, as Dr.

Ko Tanaka drifted in medicated sleep, and her vital signs slowly stabilize, Sergeant Luis Morales stood in the rain and smoked a cigarette, his third of the night.

Or was it morning now? He had lost track of time somewhere around hour five of the surgery around the moment when he realized that Captain Hayes was actually going to save the Japanese woman’s life was actually going to use up precious resources on an enemy combatant while American soldiers waited for treatment in the main ward.

The men were angry.

Morales could feel it like electricity in the air before a lightning strike.

They whispered in the barracks, muttered in the messaul, questioned Hayes’s judgment, questioned his loyalty, questioned whether a man who would save an enemy could be trusted to lead them.

Morales understood their anger, shared it even.

His cousin had died at Guadal Canal, shot by Japanese soldiers while trying to surrender.

His body never recovered.

His mother still kept a photograph of him on the mantel, still set a place for him at family dinners, still refused to accept that her son was gone forever.

How could Morales explain to her that the army doctor at Fort Bliss had spent 9 hours saving a Japanese surgeon’s life? How could he make her understand that Hayes had used plasma and instruments and supplies that could have saved American boys he could not? There was no explanation that would make sense, no justification that would satisfy the grief and rage that came from losing someone you loved to an enemy’s bullet.

But but Morales had been in the surgical theater when they brought in the Japanese woman’s medical kit.

Had been there when Major Frank Cooper from intelligence opened the metal box and found the journal.

Had watched Cooper’s face change as he read the entries.

Had seen the names, the American names, the British names, the Australian names, all of them prisoners.

All of them treated by the woman on the operating table.

John Mitchell, Norfolk, Virginia, Thomas O’Brien, Boston, Massachusetts.

Robert Chen’s aunt, Cheni Ling, Shanghai, China.

237 names.

237 soldiers who might still be alive because a Japanese surgeon had risked her life to save theirs.

Morales took another drag on his cigarette, watched the rainfall, thought about his cousin, about how his mother would give anything to know where her son was buried.

To have some kind of closure, some kind of answer.

If this Japanese woman’s journal could give that gift to other mothers, other wives, other children waiting for news, then maybe Hayes was right.

Maybe she deserved to live.

Maybe mercy was not weakness after all.

Maybe it was the only thing that separated them from the monsters they were fighting.

Maybe the rain continued to fall.

Morning would come soon, and with it questions, accusations, demands for explanation.

But for now, in the quiet hours before dawn, a Japanese surgeon slept under American guard in an American hospital.

Her life saved by an American doctor who chose to honor his oath over his hatred.

And somewhere in the darkness, the ripples of that choice began to spread outward like waves on still water, touching lives in ways that no one could yet imagine.

237 names in a journal, nine hours of surgery, one decision to choose mercy, and somewhere in that equation, something larger than any individual, larger than war, larger than nationality.

Humanity, raw and imperfect, incapable of both terrible cruelty and unexpected grace.

The war would end in ours.

The emperor would announce Japan’s surrender.

The killing would stop.

But the consequences of the choices made in wartime would echo for generations.

For better or worse, this night at Fort Bliss Army Hospital would become part of that echo.

Part of the story of what humans could be when they chose compassion over hatred.

When they chose to see the person behind the uniform.

When they chose to honor the oaths that bound them to something greater than nations or flags or all the temporary divisions that war created.

Morales finished his cigarette, dropped it in the mud, crushed it under his boot.

Then he turned and walked back into the hospital, ready to face whatever consequences came from the night’s events.

Ready to stand with Hayes even if the rest of the camp turned against them.

Ready to defend the decision to save an enemy’s life because sometimes the right choice was also the hardest one.

And sometimes mercy required more courage than hatred ever could.

Inside, Dr.

Ko Tanaka continued to heal, continued to breathe, continued to live, and with each breath, the impossible became real.

The enemy became human.

And the world tilted just slightly toward grace.

Ko awoke to whiteness.

Pure, clean, impossible whiteness that could not exist in the world, she remembered.

Not in the wreckage of a crashed plane.

Not in the dust of a Texas desert.

Not in the fever dreams of a dying woman who had made peace with her ending.

The ceiling above her was concrete painted white, unmarked, except for a single crack running from corner to corner like a river on a map.

She traced its path with her eyes the small geography of imperfection in an otherwise sterile world and tried to remember where she was.

Tried to assemble the fragments of memory into something coherent.

Pain arrived first, sharp and immediate in her abdomen, radiating outward in waves that made breathing difficult.

But it was clean pain, surgical pain, the kind that came from healing, not dying.

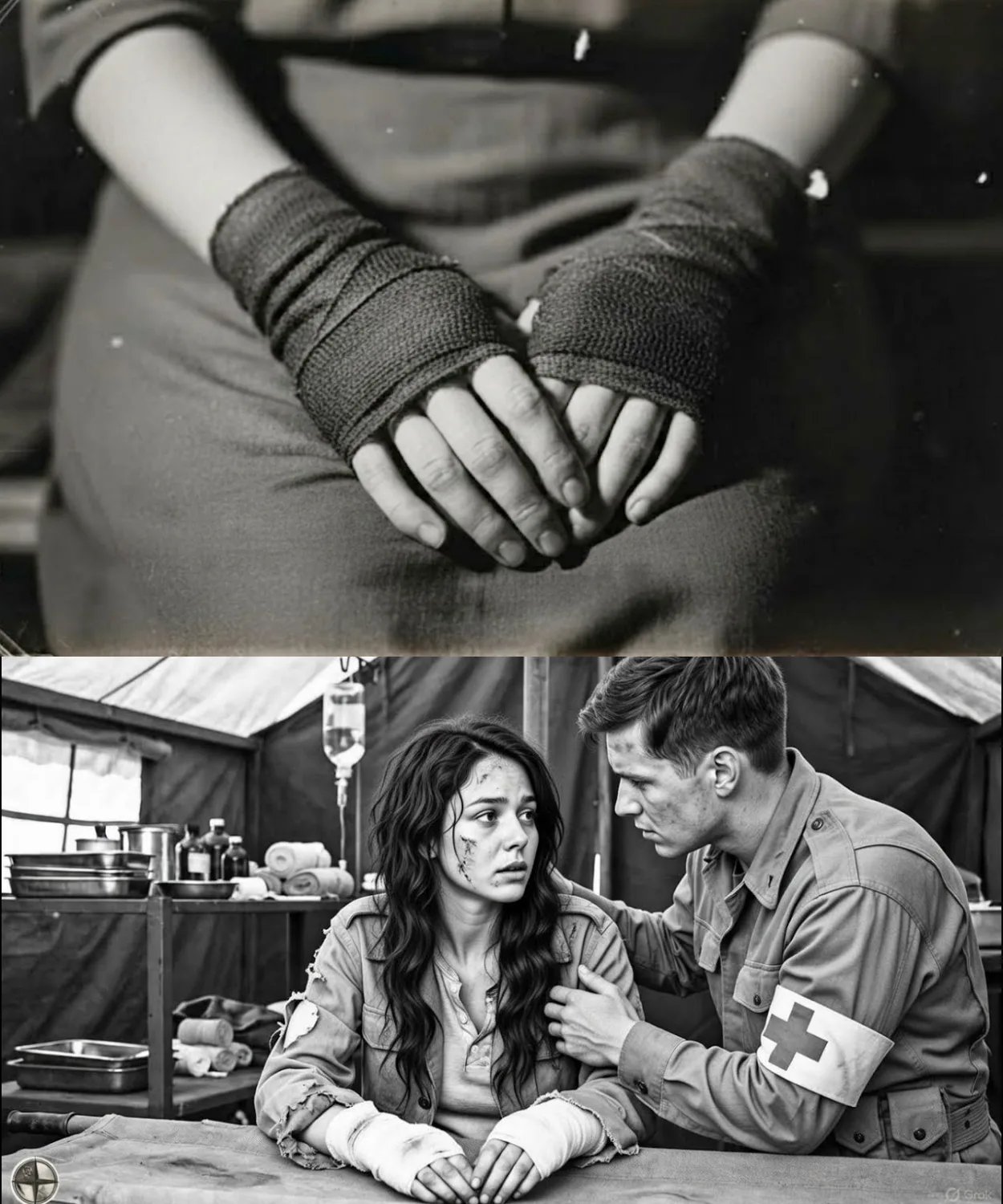

Her hands moved instinctively to the source, found thick bandages wrapped around her torso, felt the tightness of sutures beneath layers of gauze.

Someone had operated on her.

Someone had saved her life.

The second sensation was sound.

A steady beeping that matched her heartbeat.

monitors, medical equipment, the ambient hum of a hospital ward, and beneath it all, voices speaking English in the corridor outside her room.

American voices, relaxed, casual, the kind of conversation that came from people who believed the danger had passed.

Memory returned in a rush.

The crash, the wreckage, American soldiers pulling her from twisted metal, the surgical theater, Dr.

Daniel Hayes’s hands inside her body, fighting to stop the bleeding, fighting to save a life that by all rights he should have let slip away into darkness.

Terror flooded through her system like ice water in her veins.

She was alive in an American hospital under American guard, a Japanese military surgeon who had served at an internment camp, who had access to Allied prisoners, who could be tried for war crimes, who could be executed for wearing the uniform of the enemy.

Ko tried to sit up.

Her abdomen screamed in protest.

She gassed the sound escaping before she could stop it and fell back against the thin pillow.

Sweat broke out across her forehead.

Her vision blurred.

The white ceiling became a white fog that threatened to pull her under again.

A door opened.

Footsteps approached.

She turned her head, the movement sending fresh spikes of pain through her midsection and found herself looking at the man who had saved her life.

Dr.

Hayes appeared older in daylight than he had looked under surgical lamps.

The lines around his eyes were deeper, the gray in his hair more pronounced.

He carried himself with the careful posture of someone who had been standing for too many hours, whose back achd from hunching over operating tables, whose hands cramped from holding instruments in positions that human anatomy was not designed to maintain.

But his eyes were kind, tired, but kind.

He moved to her bedside with the practiced efficiency of a physician checking on a patient.

No wasted motion, no unnecessary flourish, just competent care delivered with the matter of fact professionalism that came from years of practice.

Easy, he said.

His voice was softer than she remembered.

Less steel, more compassion.

You’ve been through major surgery, 9 hours.

You’re going to survive, but you need to stay still.

Those sutures won’t hold if you try to move too soon.

Ko stared at him, tried to find words in English.

Her mind felt sluggish, wrapped in cotton, still fighting through the aftermath of anesthesia and trauma and three days of dehydration in the desert heat.

Why, she finally managed.

The single syllable came out as a croak.

Her throat was raw from the breathing tube they must have used during surgery.

Hayes pulled a chair closer to the bed, sat down with a slight wse that suggested his own body was protesting the long night.

He regarded her for a long moment before answering.

And in that moment, Ko saw something in his face that terrified her more than anger would have.

She saw understanding, recognition, the look of one physician seeing another and acknowledging the burden they both carried.

Because you’re a surgeon, Hayes said quietly.

Like me.

And because we found your journal.

The world stopped.

Ko’s breath caught in her chest.

The metal box.

The journal.

237 names written in her careful handwriting.

evidence of every law she had broken, every order she had disobeyed, every risk she had taken to save enemy lives.

They knew her face must have shown her terror because Hayes raised a hand in a placating gesture.

“You’re not in trouble,” he said.

“At least not the kind you’re thinking.” Major Cooper from intelligence has the journal now.

“He’s been going through it since we found it in your medical kit, reading the entries, cross-referencing names with missing person’s reports.” Hayes paused.

Something shifted in his expression, something that looked like respect.

You saved a lot of American lives, Dr.

Tanaka.

237 documented cases.

Allied prisoners that you treated in secret at Crystal City.

Men who were supposed to die from neglect or infection or simple cruelty.

You risked your life to honor your oath.

That counts for something.

Ko closed her eyes, felt tears sliding down her temples into her hair.

She had not cried when her family died.

Had not cried when the guards beat her at Crystal City.

Had not cried through three days of slowly dying in airplane wreckage.

But now hearing an enemy soldier acknowledge what she had done.

Hearing him say it mattered.

The damn broke.

I am sorry, she whispered.

For everything my countrymen did.

For all the pain.

I cannot undo it.

I can only try to heal what I can reach.

You did more than try.

Hayes said.

His voice was gentle but firm.

You succeeded.

And now we’re going to make sure your work wasn’t in vain.

In a windowless office three buildings away from the isolation ward where Ko recovered, Major Frank Cooper spread the journal pages across a metal desk and tried to comprehend what he was reading.

22 years in army intelligence had taught him to approach everything with skepticism, to question sources, to verify information, to assume deception until proven otherwise.

But this journal was different.

The level of detail was extraordinary.

Each entry contained not just names and service numbers, but specific medical information, injuries, treatments, dates, and most critically transferred locations.

Every prisoner that Dr.

Tanaka had treated.

She had documented where they were sent after Crystal City, Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Cabanatuan Camp in the Philippines, Andersonville in Georgia, a dozen other locations scattered across the American Southwest and the Pacific Theater.

Cooper’s assistant, Lieutenant Sarah Mitchell, stood across the desk with a telegram clutched in her hand.

Her face was pale.

Her engagement ring caught the fluorescent light as her fingers trembled against the yellow paper.

Sir,” she said.

Her voice was steady despite the tears streaming down her face.

“My fiance, John Mitchell.

He’s on this list.” Cooper looked up sharply.

Mitchell had been engaged to a Marine who went missing at Eoima, listed as MIA, presumed dead.

The service had sent condolence letters.

His personal effects had been returned to his family.

Everyone assumed he was gone.

“Show me,” Cooper said.

Sarah crossed to the desk, placed the telegram beside the journal, pointed to an entry dated July 15th, 1944.

John Mitchell, Norfol, Virginia.

Gunshot wound left shoulder treatment shrapnel removal infection debridement.

Transferred to Fort Sam Houston, San Antonio, Texas.

Condition stable.

Cooper picked up the telegram.

Read it once.

Read it again.

The words did not change.

John Mitchell, Sergeant USMC, alive.

Fort Sam Houston Hospital, San Antonio, requesting immediate contact with fiance Sarah Mitchell, Lieutenant US Army Nurse Corps.

Alive after 2 years of believing him dead.

After mourning, after accepting that she would never see him again.

After learning to live with the hollow ache of loss that came from loving someone who went to war and never came home.

He was alive.

and he was alive because a Japanese surgeon had documented his transfer location in a secret journal that she kept at the risk of her own execution.

Sarah’s legs gave out.

Cooper caught her elbow, guided her to a chair.

She sat heavily, the telegram still clutched in her hand, her entire body shaking with the force of emotions too large to contain.

She saved him, Sarah whispered.

That woman, that enemy, she saved Jon and she documented where he went.

And now I know after all this time I know.

Cooper returned to the journal, started counting entries, started calculating the magnitude of what Dr.

Tanaka had done.

237 prisoners documented.

How many of them were still listed as missing? How many families were waiting for news that this journal could provide? He reached for the phone, started making calls.

Red Cross, Missing Person’s Bureau, theater commands across the Pacific.

Every entry in this journal was a thread that could be pulled, a connection that could be traced, a possibility that someone’s son or husband or father might still be alive.

The ripples were just beginning.

Ko woke again to find a young man standing at the foot of her bed.

He could not have been more than 19 with the kind of face that had probably looked 12 until very recently.

Sandy hair cut military short, freckles across his nose.

A Texas accent thick as honey when he spoke.

“Ma’am,” he said nervously.

“Doc says you can eat now.

I uh I brought you breakfast.” He held a tray like it contains something precious and fragile.

Set it carefully on the bedside table.

Stepped back with the uncertain posture of someone who did not know if his offering would be accepted or rejected.

Ko pushed herself into a sitting position.

The movement hurt, but less than before.

Her body was healing, knitting itself back together with the resilience that had allowed her to survive 3 days in wreckage and 9 hours on an operating table.

She looked at the tray and stopped breathing.

Bacon, six strips, perfectly cooked, crispy at the edges, but still tender in the center.

The fat glistening, the smell rich and smoky and utterly overwhelming after months of eating rice and fish scraps at Crystal City.

Beside it, scrambled eggs, fluffy and golden, real eggs, not powdered, folded over themselves in soft waves, toast with butter melting into the bread, turning it glossy, orange juice in a glass that caught the morning light, and a small green bottle with familiar script.

CocaCola.

The young man saw her staring, shifted his weight from foot to foot.

It’s what we eat, he said.

Texas breakfast.

My mama makes it every Sunday after church.

I thought, well, I thought you might be hungry after surgery and all.

Ko could not speak.

Could not find words at adequate to the moment.

This boy, this American soldier who should hate her, who had every right to refuse her even basic sustenance, had brought her a meal from his own culture, had shared something precious, had offered kindness where he could have offered cruelty.

Her hand reached for the bacon before her mind fully engaged, picked up a strip, felt the texture, crispy exterior, the give of meat beneath.

She raised it to her lips.

The first bite exploded across her senses like a revelation.

Salt, smoke, fat rendered to the perfect balance between liquid and solid.

Richness that coated her tongue.

Flavor so intense after months of bland rations that it felt almost painful.

She chewed slowly, savoring every molecule, feeling tears streaming down her face again.

The young man panicked.

Ma’am, did I do something wrong? Is it bad I can get you something else I can? Ko shook her head, swallowed, found her voice.

No, you did something kind.

After everything, you give me kindness.

She took another bite.

Let the bacon crunch between her teeth.

Let the flavor fill her mouth.

Let herself experience this small miracle of generosity from an enemy who chose to be human instead.

The soldier relaxed slightly, managed a small smile.

Name’s Billy Carter.

Ma’am, private from a ranch outside Abalene.

My folks raise cattle, so I know good bacon when I taste it.

He paused, looked uncomfortable again.

Dr.

Hayes told us what you did at Crystal City.

How you saved all those prisoners.

My daddy always says you judge a person by what they do when nobody’s watching.

When it cost them something, I reckon you paid a price for being decent.

Ko finished the bacon, moved to the eggs, soft and rich and perfect.

Then the toast.

The butter had soaked in, making each bite an exercise in simple pleasure.

Finally, she picked up the Coca-Cola, twisted the cap, heard the hiss of carbonation, escaping, raised the bottle to her lips.

The first swallow was cold fire, sweet and sharp, and fizzing on her tongue.

The bubbles tickled her throat.

The sugar hit her system like electricity after months without.

She had drunk Coca-Cola in San Francisco during medical school.

had loved it then, but this bottle in this moment tasted like more than sugar water and carbonation.

It tasted like acceptance in Japan, she said softly, we heard propaganda.

Americans are cruel, they said.

Americans are devils.

They will torture you.

They will show no mercy.

She took another sip of Coca-Cola cola.

Let the sweetness linger, but you give me bacon and eggs and this and mercy.

The propaganda was lies.

Billy Carter’s expression shifted.

Something proud and sad at the same time.

Well, ma’am, reckon every side tells lies in wartime.

Makes it easier to kill people if you think they’re devils instead of just folks who happen to be on the other team.

He collected the empty tray, paused at the door.

You rest up now.

Doc says you’re healing good, but you got a ways to go yet.

He left.

The door clicked shut.

And Ko sat alone in the white room with a taste of bacon and Coca-Cola cola still lingering on her tongue, feeling the world she thought she understood shifting beneath her like sand.

The door opened again an hour later, this time a different visitor.

Robert Chen entered slowly, his face a mask of controlled emotion.

He stood at the foot of the bed without speaking, just looking at her with eyes that held depths of pain she recognized because she carried the same burden.

Finally, he spoke.

His voice was tight.

Each word carefully chosen.

My aunt Chen Ling, Shanghai.

You documented her death.

Ko went very still.

Remembered a woman in her 40s.

Dysentery.

No medicine available at Crystal City because the camp commander diverted supplies to American internees and let the foreign prisoners suffer.

Ko had tried everything.

Clean water, rehydration, basic nursing care.

But without proper medicine, Dysentery killed slowly and horribly.

Chenuing had died in Ko’s arms on a March morning in 1942, and Ko had written down her name.

Had documented her existence, had tried to give her the dignity of being remembered.

“I remember her,” Ko said quietly.

“I had no medicine, only water, clean cloth.

She died.” “I am sorry.

I wrote her name so someone would remember.

So she would not be forgotten.” Chen’s jaw worked.

His hands clenched at his sides.

You’re Japanese.

Your soldiers killed her.

Raped Nang King.

Destroyed Shanghai.

Murdered my family.

Yes, Ko said.

She did not look away.

Did not try to justify or explain.

Just acknowledge the truth.

Chen took a shaking breath.

But you wrote down her name.

You cared enough about a Chinese woman to remember her, to document her death with respect, to treat her like she mattered.

His voice broke.

I don’t know how to hate you and thank you at the same time.

Ko met his eyes, saw the war there, the struggle between rage and gratitude, between the desire for revenge and the recognition of shared humanity.

Then do not, she said softly, just remember her.

That is all I could give her memory.

Chen stood silent for a long moment.

Then he nodded once.

Sharp and melodistry turned and left without another word.

But something had shifted.

Something had changed.

One more connection made across the divide of nationality and uniform and all the lies that war told to make killing easier.

One more small victory for the idea that people were more than the flags they served.

August 15th, 1945.

The day the world changed.

Ko heard the commotion before she understood what it meant.

Shouting in the corridors, running footsteps, the sound of celebration.

Men’s voices raised in joy and relief and the kind of primal release that came when fear finally ended.

A nurse burst into her room, young, pretty, face flushed with excitement.

It’s over, though.

The war’s over.

Emperor Hirohito just announced Japan’s surrender.

She was gone before Ko could respond.

Gone to join the celebration.

To kiss soldiers, to throw her cap in the air, to scream with joy that the killing had finally stopped.

Ko lay in bed and listened to the sounds of American victory.

Heard bottles clinking.

Heard someone playing a trumpet badly.

Heard laughter and singing and all the noises that accompanied the end of the worst war in human history.

And she wept not from joy, from devastation.

Her country had surrendered, had accepted total defeat, had bowed to terms that would reshape Japan forever.

The empire was gone.

The military was dismantled.

Everything her father’s generation had built, everything they had believed in reduced to ash and rubble and the bitter taste of unconditional surrender.

Hiroshima, Nagasaki, two cities erased in atomic fire.

Her family among the hundreds of thousands dead.

Her home destroyed.

Her culture shattered.

She had no country to return to.

No family waiting.

No place in the world that wanted her.

Dr.

Hei found her curled on her side, sobbing silently into the thin pillow.

He entered without knocking, stood by the bed, said nothing, just pulled the chair close and sat down.

He did not offer platitudes.

Did not tell her it would be okay.

did not try to minimize her grief with hollow words about necessary sacrifice or justified violence.

He just stayed.

Sometimes she would realize later presence was the only medicine that mattered.

Sometimes the greatest gift one human could give another was simply to witness their pain without trying to fix it or explain it away.

Hayes sat with her for an hour while she cried for everything she had lost.

for her family, for her country, for the world that had existed before atomic bombs taught humanity what total war truly meant.

“When the tears finally stopped when her body had exhausted itself and left her hollow and empty,” Hayes spoke.

“The tribunal convenes next week,” he said quietly.

“You’ll be questioned about your service at Crystal City, about the prisoners you treated, about the journal.” Ko closed her eyes, waited for the rest, waited for him to tell her she would be tried for war crimes, executed for serving the enemy, punished for wearing the wrong uniform in the wrong war.

But Hayes continued in that same quiet voice.

I’m testifying on your behalf.

So is Lieutenant Mitchell.

So is Corman Chen.

So are 47 liberated prisoners who were found using coordinates from your journal.

Men who are alive because you documented where they were transferred.

Families who are reunited because you cared enough to keep records.

He paused.

You won’t be convicted, Ko.

You’ll be recognized as what you are.

A physician who honored her oath even when it meant risking everything.

A humanitarian who chose mercy over obedience.

A surgeon who saved lives regardless of nationality.

Ko opened her eyes, looked at him through the blur of tears.

Why do you do this? Why fight for enemy? Hayes smiled.

Tired but genuine.

Because you’re not the enemy anymore.

The war’s over.

Now you’re just a doctor who saved lives.

Same as me.

And doctors look out for each other.

He stood, moved toward the door, paused with his hand on the handle.

Rest up.

The tribunal will want you strong enough to testify.

And after that, we’ll figure out what comes next.

He left.

And Ko lay in the white room processing the impossible idea that she might survive not just the surgery but the war itself.

That mercy might prove stronger than hatred.

That the oath she had honored at such cost might actually mean something in a world that had just learned what atomic weapons could do to cities full of civilians.

Outside the celebration continued.

America had won.

Japan had lost.

But in the spaces between victory and defeat, in the gray areas where propaganda gave way to truth, something else was happening.

Something quieter, but perhaps more important.

Enemies were becoming humans again.

Hatred was giving way to understanding.

And the ripples of one insurgent’s decision to save another surgeon’s life were spreading outward in ways that no one could yet fully comprehend.

237 names in a journal, nine hours of surgery, one decision to choose mercy, and now the beginning of something new, something that looked almost like redemption, almost like hope.

The war was over, but the work of healing had only just begun.

The San Antonio military court convened on September 23rd, 1945 in a limestone building that had witnessed a 100red years of Texas justice.

Ko sat in the defendant’s chair wearing a borrowed dress that hung loose on her frame, still 20 lbs underweight from the crash and surgery in months of inadequate rations before that.

Her hands rested folded in her lap, trembling slightly despite her efforts to keep them still.

The charges were read in English that she understood perfectly from her years at UC San Francisco.

Serving enemy military forces at an interment facility, potential collaboration with hostile regime, possible war crimes committed against Allied prisoners of war.

Each charge carried the possibility of execution.

The tribunal consisted of three officers, a colonel, a Navy captain, a brigadier general with more medals on his chest than Ko could count.

They looked at her with faces that revealed nothing.

professional, clinical, the expressions of men trained to make difficult decisions based on evidence rather than emotion.

The prosecution presented first, documented her service record, her assignment to Crystal City, her access to Allied prisoners.

They built a case that suggested complicity in the camp’s conditions.

That implied she had been part of the machinery that kept enemy soldiers in substandard circumstances that violated Geneva Convention protections.

Ko listened without defending herself.

What could she say? The charges were technically accurate.

She had served at Crystal City.

She had worn the uniform of Imperial Japan.

She had been present while Allied prisoners suffered.

That she had also saved 237 of them in secret was a detail that would come later.

The defense called its first witness.

Dr.

Daniel Hayes took the stand in full uniform, his captain’s bars gleaming under the courtroom lights.

He spoke for three hours, detailed the surgery, explained the journal, read entry after entry to the record, names and dates and medical procedures performed in secret at great personal risk.

He described finding Ko in the wreckage, the shrapnel against her aorta, the impossible complexity of the surgery, the moment he decided to save her life despite every reason to let her die.

And then he said something that made Ko’s breath catch.

Dr.

Dr.

Tanaka is the finest surgeon I have ever encountered.

Her documentation is meticulous.

Her technique is flawless.

Her commitment to the hypocratic oath transcends nationality.

She saved American lives when her own commanders ordered her to let them die.

She risked execution to honor the same oath that I took when I became a physician.

If that is a war crime, then we have defined the term incorrectly.

The second witness was Lieutenant Sarah Mitchell.

She approached the stand with her engagement ring visible on her left hand, new, shining, a symbol of the future that had been returned to her.

Sarah’s voice was steady as she testified, described learning that her fiance was alive, explained how Dr.

Tanaka’s journal had documented John Mitchell’s transfer to Fort Sam, Houston, how that single entry had reunited them after 2 years of believing he was dead.

She looked directly at the tribunal members.

My fiance is alive because Dr.

Tanaka refused to let hatred guide her hands.

Our children will exist because she chose to honor her oath.

47 families have been reunited because she kept records that she could have been executed for maintaining.

If you convict her, you are convicting the woman who gave me back my future.

Corman Robert Chen testified about his aunt, about finding her name in the journal, about the dignity of knowing what had happened to her, about the impossible conflict of hating and thanking the same person.

But mostly he said quietly, “I learned that the enemy is only the enemy until someone chooses to see them differently.” Duranaka saw my aunt as a person who deserve respect even in death.

That mattered more than nationality or uniform or any of the divisions that war creates.

The 47 liberated prisoners testified in groups.

Men who had been found at Fort Sam Houston, at Cababanatuan, at camps across the southwestern Pacific.

Men whose families had believed them lost forever.

They spoke of the Japanese surgeon who operated by candlelight, who gave her own food rations, who risked everything to save lives that her commanders had deemed worthless.

John Mitchell took the stand last.

His left shoulder still showed scarring from the gunshot wound that should have killed him.

Would have killed him without intervention.

Dr.

Tanaka dug shrapnel from my shoulder in a storage shed at Crystal City.

He said she hid from guards.

She used instruments she had smuggled from the medical building.

She gave me her dinner rations for 3 weeks while I healed.

She argued with the camp commander to get me transferred to safety instead of the labor camps where men died within weeks.

He paused.

His voice broke.

Without her, I am dead.

My fiance never knows what happened to me.

Our children are never born.

She is not a war criminal.

She is a hero who wore the wrong uniform.

The tribunal deliberated for 4 hours.

Ko sat in a holding room with Dr.

Hayes beside her, waiting for the verdict that would determine whether she lived or died, whether mercy would be recognized or punished, whether her oath had meant anything at all.

Hayes did not try to reassure her with false optimism, just sat quietly present in the way that had become familiar during her recovery, offering the gift of companionship in the face of uncertainty.

When they were called back, Ko walked to the defendant’s chair on legs that barely supported her weight, stood while the brigadier general read the verdict.

Not guilty on all charges.

The words took a moment to penetrate, to become real.

Not guilty.

The general continued speaking.

His voice was formal, but something else lurked beneath the official tone, something that sounded almost like respect.

Detctor Ko Tanaka is hereby recognized as a humanitarian who served with distinction under impossible circumstances.

Her documentation of Allied prisoners resulted in the liberation of 153 men and the reunification of 47 families.

Her actions exemplify the highest standards of medical ethics and human decency.

He paused.

Dr.

Tanaka is granted asylum in the United States.

She will be permitted to remain in this country and practice medicine under civilian license.

The tribunal recommends that she be considered for recognition by the International Red Cross for her humanitarian service.

Ko’s legs gave out.

Hayes caught her.

Held her upright while the courtroom erupted in applause.

While Sarah Mitchell wept, while Robert Chen nodded slowly from the back row, while John Mitchell stood and saluted the woman who had saved his life, not guilty, recognized as a humanitarian, granted asylum.

The impossible had become real.

Mercy had been rewarded.

Her oath had mattered after all.

3 days later, Billy Carter appeared at her hospital room door with that same nervous energy he had carried when bringing breakfast months earlier.

But this time he held not a tray but an invitation.

Ma’ammy said before you head to California, you got to experience real Texas hospitality.

My daddy’s having a barbecue tonight.

Whole ranch is coming.

He says any friend of mine is welcome and I told him about what you did about the journal and the prisoners and all of it.

Billy shifted his weight.

He wants to meet you proper.

Wants to thank you himself.

His brother was at Baton died in the camps.

But knowing there were decent folks like you trying to help, well, it matters to him.

Ko sat in the chair by the window, strong enough now to move without assistance, but still careful of the healing incision across her abdomen.

She had been preparing to leave Fort Bliss, to travel to San Francisco, where she would attempt to rebuild a life from the ashes of everything she had lost.

But this invitation felt important, felt like something that required witnessing.

“I would be honored,” she said.

The Carter Ranch sat 30 mi outside Fort Bliss, accessible only by dirt roads that cut through Msquite and sagebrush in the kind of vast emptiness that defined West Texas.

The sun was setting as they arrived, painting the sky in layers of orange and purple and deep crimson that looked like something from a painting rather than reality.

Ko stepped out of the Jeep and stopped breathing.

The smell hit her first.

Mosquite smoke, rich and sweet and utterly unlike anything in her experience.

It carried on the evening breeze along with the sound of men’s laughter and the crackle of fire and the low mooing of cattle in distant pens.

Billy led her around the house to the backyard where a massive smoker dominated the space.

6 ft long, metal construction blackened by years of use, heat radiating from it in waves that made the air shimmer.

Billy’s father stood beside the smoker, tending meat with the focused attention of an artist working on a masterpiece.

He was perhaps 60 years old, weathered skin that spoke of decades under the Texas sun, hands scarred from ranch work, eyes that held both sorrow and kindness in equal measure.

He looked up as they approached, “Studied Ko for a long moment.

Then he smiled.” “Doc Tanaka,” he said.

His voice was deep, textured like wood grain.

Name’s William Carter.

This here’s my ranch, my barbecue.

And you are most welcome.

He extended a hand.

Ko took it.

His grip was firm but gentle.

The handshake of someone who knew his own strength and chose to temper it with care.

Billy tells me you saved a lot of boys who should have died.

William saids you risked your neck to do right by folks who were supposed to be your enemy.

That takes sand.

That takes character.

Far as I’m concerned that anyone with that kind of backbone is is Texas enough for me no matter where they were born.

He gestured to the smoker.

Been cooking this brisket since dawn.

16 hours low and slow over mosquite.

That’s how we do things here.

We take our time.

We do it right.

And we share what we make with anyone who needs feeding.

He opened the smoker.

Smoke billowed out, carrying with it a smell so rich and complex that Ko felt her knees go weak.

Inside a brisket the size of a small child rested on metal grates.

The exterior was dark, almost black.

A pepper crust that had formed during the hours of smoking.

But when William poked it with the fork, the meat fell apart, tender beyond imagination.

Pink smoke ring visible where the meat had absorbed flavor from the burning mosquite.

William lifted the brisket onto a cutting board.

Began slicing.

Each piece revealed interior texture that looked like marbled art.

fat rendered to gelatin.

Meat so tender it barely held together.

Juice running onto the board.

He handed Ko a plate.

Piled it high with brisket.

Added colelaw made with vinegar and pepper that would cut through the richness.

Beans cooked with bacon and molasses.

Fresh cornbread still warm from the oven.

A jar of sweet tea that caught the last rays of sunlight and glowed like amber.

She found a seat at a long table made from rough huneed wood.

around her.

Ranch hands and soldiers and neighbors gathered.

20 people, 30, all of them sharing food and stories and the easy camaraderie that came from community built over generations.

Ko picked up a slice of brisket with her fork, raised it to her mouth.

The first bite stopped the world.

The smoke flavor hit first.

Deep and sweet from mosquite wood burned down to coals over 16 hours.

Then the pepper crust, spicy and aromatic.

Then the meat itself falling apart on her tongue.

Fat melting like butter.

Texture so tender it required almost no chewing.

Richness that filled her mouth and throat and seemed to spread warmth through her entire body.

She closed her eyes, felt tears streaming down her face for the hundth time since waking in the American hospital.

But these were different tears.

These were tears of overwhelming gratitude, of recognition that kindness existed even in a world that had just demonstrated its capacity for atomic horror.

“This is love,” she whispered.

William Carter, sitting across from her, smiled.

“Yes, ma’am.

That’s exactly what it is.

Time and care and sharing what you have with folks who need it.

That’s the best of what we are.

That’s what’s worth preserving when everything else goes to hell.” She ate slowly, savoring every bite.

The brisket, the coleslaw that provided acid to balance the fat, the beans that added sweetness, the cornbread that soaked up juice and completed the symphony of flavors.

Around her, people talked and laughed, told stories about the war ending, about brothers and sons coming home, about the future they would build now that the killing had stopped.

And they included her in their circle, passed her dishes, refilled her tea, treated her not as enemy or outsider, but as guest, as human, as someone worthy of sharing their table.

Billy’s father raised his jar of tea.

A toast, he said.

The table quieted to Dr.

Tanaka, who proved that decency transcends nationality.

Who honored her oath when it cost her everything.

Who saved our boys and kept records that brought them home.

You are Texas now, Doc, and that means you are family.

30 voices echoed the sentiment.

30 jars raised in her direction.

30 people choosing to see past uniform and accent in the divisions that war had created.

Ko raised her own jar, found her voice.

Thank you for showing me that the propaganda was lies, that Americans are not devils, that mercy exists, that humanity survives even in darkest times.

She drank.

The sweet tea was perfect, cold and refreshing and exactly right to cut the richness of the brisket still coating her tongue.

And in that moment, surrounded by strangers who had chosen to become friends, eating food prepared with love and time and the kind of care that transformed ingredients into art, Ko understood something profound.

She had survived not just the crash and the surgery and the tribunal.

She had survived the war itself with her oath intact, with her humanity preserved, with the belief that healing mattered more than hatred.

The American values she had been taught to despise had saved her life, had recognized her worth, had offered her not punishment, but asylum, not rejection, but welcome.

The propaganda had been lies.

All of it.

And the truth was both simpler and more complex.

Americans were just people capable of both terrible cruelty and unexpected grace just like Japanese, just like everyone.

And maybe, just maybe, that recognition was enough to build a future on.

September 30th, her last day at Fort Bliss before the journey to California and whatever came next.

Doctor Hayes found her packing the few belongings she had accumulated.

Medical texts he had lent her, a nurse’s uniform Sarah had given her to replace the tattered ones she had arrived in.

The journal returned to her after the tribunal, its pages worn from being studied by intelligence officers who had used it to reunite families and liberate prisoners.

Hayes carried something wrapped in cloth, set it carefully on her bed.

Before you go, he said, I want you to have something.

Ko unwrapped the cloth.

Inside lay the surgical instruments that had saved her life.

Scalpels, forceps, retractors.

Each one carefully cleaned and maintained.

Each one carrying the memory of 9 hours in an operating theater where an enemy became a patient and a patient became a person.

I cannot accept, she whispered.

Yes, you can, Hayes said firmly.

You are a surgeon.

These instruments are meant to save lives.

That is what you do.

That is who you are.

Take them to California.

Use them to rebuild.

Use them to teach.

Use them to prove that medicine transcends borders.

Ko’s hands trembled as she touched the instruments.

Felt the weight of them, the responsibility they represented.

Then I will honor them, she said.

I will honor you by saving as many lives as I can by teaching the next generation that our oath is to humanity, not to flags or nations or any of the divisions that humans create.

She reached into her own bag, pulled out something small and delicate.

An origami crane folded from surgical gauze with meticulous precision.

Each crease perfect, each angle exact.

A small work of art created during her recovery.

In Japan, she said the crane symbolizes hope, healing.

1,000 cranes can grant a wish.

I cannot fold 1,000, but I give you this one to remember that your mercy saved more than just me.

It saved everyone in the journal.

Everyone who comes home because you kept me alive.

Hayes took the crane carefully, held it in his palm like it was made of glass.

I will keep it always, he said.

And I will tell every medical student who passes through my office about the surgeon who honored her oath, even when it meant risking everything.

about the enemy who became a colleague.

About the proof that mercy is stronger than hatred.

They stood in silence for a moment.

Two physicians, former enemies, now connected by something deeper than nationality or uniform, connected by the shared understanding that healing mattered, that oaths meant something, that humanity could survive even the worst that war could inflict.

Hayes extended his hand.

Ko took it.

The handshake became an embrace.

Brief but genuine.

the acknowledgement of respect earned and freely given.

“Thank you,” she whispered.

“For everything.” “Hey,” stepped back, smiled.

“Thank you for proving that the enemy is only the enemy until someone chooses to see them differently.

You changed how I think about a lot of things, Ko.

You made me better.” He left.

And Ko finished packing, ready to begin the next chapter, ready to take the gift of borrowed time and use it to build something meaningful.

The war was over.

Her family was gone.

Her country had surrendered.

Everything she had known was ash.

But she was alive and she had her oath.

And she had instruments that carried the memory of mercy received.

That would be enough.

It would have to be enough.

20 years passed like water flowing through cupped hands.

Ko built a life from the ruins.

Returned to San Francisco where she had studied medicine in what felt like another lifetime.

found work in a clinic treating Japanese-American internes returning to homes that had been seized or destroyed, used the instruments Hayes had given her to perform surgeries that saved lives and trained the next generation.

In 1948, UC San Francisco offered her a faculty position, one of the first women to teach at the medical school.

She created a new curriculum that emphasized humanitarian medicine that taught students about the obligation to treat all patients regardless of nationality or status.

And she told them the story about the American surgeon who saved an enemy’s life, about the 9-hour surgery, about the journal that reunited families, about the proof that medicine transcended borders.

Every student who passed through her program learned about Dr.

Daniel Hayes, about his choice to honor his oath over his hatred, about the ripple effects of one decision to show mercy.

She corresponded with Hayes over the years.

Letters crossing the country every few months.

News of lives saved and students trained.

Updates on how the journal had continued to help locate missing soldiers years after the war ended.

Photographs of Sarah and John Mitchell’s growing family.

Evidence that her documentation had created futures that otherwise would never have existed.

In June of 1965, Ko received an invitation to a medical conference in San Francisco.

The keynote speaker was listed as Dr.

Daniel Hayes, professor of surgery at at Baylor College of Medicine.

The topic, medical ethics in wartime.

She met him at the airport.

He was 64 now, gray-haired and moving more slowly than she remembered.

But his eyes were the same, kind and tired, and carrying the weight of too many surgeries and too many difficult decisions.

He still carried the origami crane, showed it to her, carefully preserved in a small glass case.

“It sits on my desk,” he said.

Every student asks about it and I tell them the truth.

That mercy is harder than hatred but infinitely more powerful.

She took him on a tour, showed him her clinic that now treated 200 patients daily.

Took him to UC San Francisco where she served as associate dean of medicine.

The first woman to hold that position.

Walked him through the memorial garden where 237 names were carved in stone.

Allied prisoners she had treated.

A reminder that even enemies deserve dignity.

They sat in her office drinking coffee, looking out at the San Francisco skyline.

The city rebuilt after the war.

Thriving, moving forward.

You gave me 40 years, Ko said quietly.

40 years I should not have had.

I have trained 206 doctors.

Each one saves dozens of lives per year.

Thousands of lives.

Tens of thousands.

All because you chose Mercy one Texas night.

Hayes shook his head.

You chose it first.

at Crystal City when you treated enemy soldiers despite orders not to when you kept records despite the danger.

I just continued what you started.

Then we saved each other.

Ko said, “You saved my body.

I gave you proof that the enemy could be redeemed.

That mercy was not weakness.

We both needed that.” Hayes smiled, pulled out a photograph.

Sarah Mitchell standing with Jon and their three children.

A family that existed because a Japanese surgeon had documented a transfer location in a secret journal.

47 families, he said.

47 descendants from the people whose names are in your journal.

Children and grandchildren who exist because you documented where prisoners were sent because I kept you alive to share that information.

He paused.

That does not even count the ones who do not know, who do not realize their grandfather or father survived because of those records.

The weight of it settled over them.

One surgery, 9 hours, 80 years of ripples spreading outward in ways they could never fully trace.

The keynote speech the next day drew 1500 doctors and medical students.

Hayes stood at the podium and told the entire story.

The dying enemy in Texas dust.

the hatred he had to overcome.

The nine-hour surgery that should have failed, the journal that saved lives, the woman who became colleague and friend.

When he finished, the auditorium was silent, then slowly starting in the back and building like thunder, everyone stood.

The applause lasted 5 minutes.

Wave after wave of recognition and respect.

Ko stood in the front row, tears streaming down her face, and bowed to the man who had saved her life.

He bowed back.

Equals partners in proving that humanity could survive even war.

The story was published in medical journals, picked up by mainstream media, became a symbol.

Two people choosing mercy when everything argued for hate.

Choosing humanity when war demanded they see each other as things to be destroyed.

Medical schools worldwide added it to their ethics curricula.

The Hayes Tanaka case study examining the moral complexity of treating enemy combatants.

the responsibility of physicians to transcend nationality.

The ripple effects of single decisions and the ripples continued spreading, growing, touching lives in ways that neither of them would live to see fully realized.

Ko died in 1985.

Cancer terminal.

Hayes flew to San Francisco, stayed by her bedside the way she had once recovered in his hospital.

I should have died in 1945, she told him during one of their last conversations.

Everything since has been borrowed time, gift time, and I spent it well, saving lives, teaching.

Because of you, because of us, Hayes corrected gently.

She smiled.

Yes, together, enemy and enemy, choosing to see each other as human.

That was the real surgery.

Cutting away hatred, suturing up humanity.

Hayes delivered the eulogy to thousands, showed them the origami crane, 40 years old and fragile, told them about the woman who proved that redemption was possible, that mercy multiplied, that one choice could echo across generations.

He died 7 years later in 1992 at age 71.

The origami crane was buried with him, placed carefully in his hands.

His will established the Hayes Tanaka Medical Exchange, sponsoring doctors to study between the United States and Japan.

continuing the bridge they had built.

Sarah Mitchell lived to 95 dying in 2020, surrounded by 47 descendants, children, grandchildren, great grandchildren in one great great grandchild.

A family tree that existed because a Japanese surgeon had documented a wounded prisoner’s location and because an American surgeon had kept that Japanese doctor alive.

At her funeral, the oldest granddaughter read from the journal.

John Mitchell, Norfol, Virginia.

Gunshot wound, left shoulder.

Treated successfully.

Transferred to Fort Sam, Houston, San Antonio.

Condition stable.

Then she looked at the 47 descendants assembled.

These words written by an enemy doctor in secret gave us all life.

She risked execution to write them.

Dir Hayes risked everything to save her.

They chose mercy when hate was easier.

And because of those choices, we are all here today.

The story is taught in medical schools across the world.

The journal sits in the Smithsonian preserve behind glass.

Hayes’s surgical instruments, the ones he gave Ko, are displayed in the UC San Francisco Medical Museum.

In both San Antonio and San Francisco monuments stand, two hands clasped, American and Japanese, surgeon and surgeon, enemy and friend.

The inscription reads simply, “She won’t survive the night, but she did because mercy is stronger than hate.” 1945 forever.

Medical students still visit, still read the plaques describing the 9-hour surgery, the journal of names, the 40 years of borrowed time spent saving lives.

And they learned the lesson that Hayes and Ko proved that our humanity is not destroyed by war.

It is tested.

And in how we respond to that test in the choices we make when everything argues against compassion, we define not just ourselves, but the world we leave behind.

One surgery, 9 hours, 80 years of ripples.

Still spreading, still teaching, still proving that mercy once given never dies.

The war ended in 1945.

But the effects of two physicians choosing to honor their oaths over their hatred continue today.

in the doctors they trained, in the lives those doctors saved, in the families that exist because one American surgeon saw past a uniform to the human being beneath.

Because one Japanese surgeon refused to let hatred guide her hands, 237 names in a journal, 206 doctors trained, tens of thousands of lives saved, hundreds of thousands touched, all because two people on opposite sides of the worst war in human history chose to see each other as human rather than enemy.

That is the legacy.

That is the lesson.

That is the proof that mercy is not weakness.

It is the strongest force we have.

And it never dies.