“I’ll Be Your Slave,” Said Surrendered Japanese POW to U.S.

Cowboy

He didn’t understand her words at first, just the way she dropped to her knees, hands trembling in the Texas dirt, eyes wide with something closer to terror than gratitude.

She clutched the hem of his jeans like they were a rope thrown overboard, her voice barely audible, thick with dust and desperation.

Watashi wa anata nodor ninarimus.

The translator hesitated, then turned to the stunned cowboy and said, “She says, I’ll be your slave.” The cowboy dropped his cigarette.

He wasn’t a soldier, just a rancher with a rifle and a rotating shift guarding PS.

He had expected hostility, maybe fear, not this.

The girl couldn’t have been more than 17.

Her knees sunk deeper into the dirt.

Her uniform was too big, held together with knots.

Her face was blank, but her voice shook with something ancient.

Obedience bred from terror.

He stepped back.

“Ma’am,” he whispered.

“You ain’t nobody’s slave.” And in that moment, something in her expression cracked.

For a second, the wind stopped.

The dust hung in the air like suspended breath.

Kaa remained on her knees, head bowed low, fingers still clenched around the cuff of the man’s jeans.

She had not understood his words, not fully, but she heard the tone, confused, quiet, not triumphant, and that was enough to confuse her.

It wasn’t what she’d expected.

She had rehearsed this moment in her head on the ship, the moment she would be beaten, or humiliated or worse.

Instead, there was a kind of stunned stillness, as if time had tripped, and everyone was waiting to see where it landed.

The cowboy shifted, the leather of his belt creaking slightly.

He looked around at the other guards, ranchers mostly, part-time soldiers with sund darkened hands and rifles, slung more out of habit than hostility.

One of them muttered something under his breath, took off his hat, and scratched the back of his neck.

Another spit in the dirt and stared out toward the long fence line as if embarrassed to be a witness.

None of them moved to lift her up.

None of them barked orders.

They just watched, and that silence, heavy and awkward, was somehow louder than shouting would have been.

A translator stepped forward.

a young ni man in a creased uniform and dusty boots.

He cleared his throat and knelt beside Kana speaking softly in Japanese.

“You don’t have to say that,” he told her.

“No one here is going to hurt you.” But she didn’t respond.

Her face stayed downcast, her shoulders trembling slightly.

The translator looked up at the cowboy, then back at Kaa.

His expression flickered.

something between pity and grief.

He had heard it before, but every time it hit different.

A girl on her knees offering her life like it was already gone, like she was a burden, not a being.

Kaa, he said again, more gently now.

Please stand.

You are not a slave.

You’re safe.

She blinked slowly.

The translator knew the look.

He’d seen it on the faces of others like her during transport.

It was the look of someone whose entire world had cracked, whose last remaining belief had just been proven false.

Because for her, this wasn’t theater.

This wasn’t survival instinct.

It was surrender in the truest sense, full, absolute, irreversible.

She had been told her value ended the moment she was captured.

Her body was no longer hers.

Her life was no longer hers.

The phrase she’d spoken, “I’ll be your slave,” was not metaphor.

It was the last line in a script she’d been handed as a child.

The cowboy didn’t know what to do.

He stood there holding his hat now, like it might shield him from this strange, quiet war he hadn’t signed up for.

He had fought in Europe, driven cattle before that, but nothing had prepared him for a girl offering herself like a broken heirloom.

Finally, he stepped back, nodded toward the translator, and said, “Tell her.

Tell her we got a bunk for her.

Some stew, a bed, that’s all.” The translator hesitated, then translated.

Ka slowly raised her head, eyes meeting the cowboys.

He didn’t look away.

She studied him for a moment, his square jaw, the lines around his mouth, the faint twitch in his fingers, and realized with dawning confusion.

He was afraid, too.

Not of her, but of doing the wrong thing.

She rose, not all the way, just enough to sit on her heels.

Her knees were dirty, her arms limp at her sides.

The translator reached down, offering his hand.

She stared at it like it was fire, then cautiously took it.

When he helped her to her feet, she swayed slightly, and the cowboy stepped forward on instinct, catching her elbow before she could fall.

She flinched, not violently, just enough for both men to freeze.

Then, slowly she writed herself.

She nodded once.

It was not gratitude.

It was habit.

They led her through the gate.

The other prisoners, Japanese women, most in torn uniforms and blank expressions, watched with unreadable eyes.

Ka didn’t look at them.

Her eyes stayed fixed on the dust below her feet, the rifle slung across the cowboy’s shoulder, the barn rising in the distance like some surreal mirage.

Inside the bunk house was dim but dry.

Sunlight filtered through the slats.

A cot had been prepared.

A wool blanket folded on top.

A tin plate waited nearby.

Steam curling from a bowl of soup.

Kana froze in the doorway.

No chains, no shouting, no punishment, just a place to sit, a place to rest.

The translator said nothing as he guided her forward.

But inside his chest, something twisted.

He had grown up in California, raised between cultures, speaking both languages, but never truly belonging to either.

And now, watching Kana, this ghost of a girl barely old enough to shave her head for war, he felt it again, the cruel absurdity of being both the bridge and the witness.

as she sat on the edge of the cot, her legs shaking.

He glanced at the cowboy, who still hadn’t put his hat back on, their eyes met, and in that look past a silent acknowledgement.

This wasn’t what they were trained for, but it was what history had handed them.

Kaa reached for the bowl, hands trembling.

The steam rose like a prayer, and for the first time in weeks, she didn’t cry.

But there had been a time when she did quietly, furiously into a motheaten futon, while the walls of her childhood home shook from distant detonations.

Long before she knelt in the dirt of Texas, Kana had walked the ashes of Nagoya, barefoot and mute, a ghost in her own country.

Her family’s roof had caved in the winter she turned 13.

After that, the wind came through like a warning, rattling the broken shutters and freezing the tears on her cheeks before they could fall.

Her school had become a rubble heap, the neighbors laundry flapped between scorched foundations.

And yet each morning she still bowed to the photograph of the emperor, her mother whispering, “Endure, Kana.

The gods reward the loyal.

” Loyalty, she was taught, meant silence.

It meant swallowing hunger without complaint.

It meant believing what the radio said, even when the rice was gone and the soldiers never came back.

It meant kneeling to a myth larger than her own name.

Bushido wasn’t for women, not officially, but its roots crept into their bones just the same.

In school, they were told stories of noble death and glorious sacrifice.

Surrender was shame.

Captivity was worse than execution.

A good woman, they said, would never let herself be taken alive.

Kaa memorized those words the same way she learned multiplication tables by repetition and fear.

When she turned 14, she was selected for service, not as a soldier, but as a tation tie, a volunteer assistant to the Imperial Army.

The word volunteer was a formality.

There was no choice.

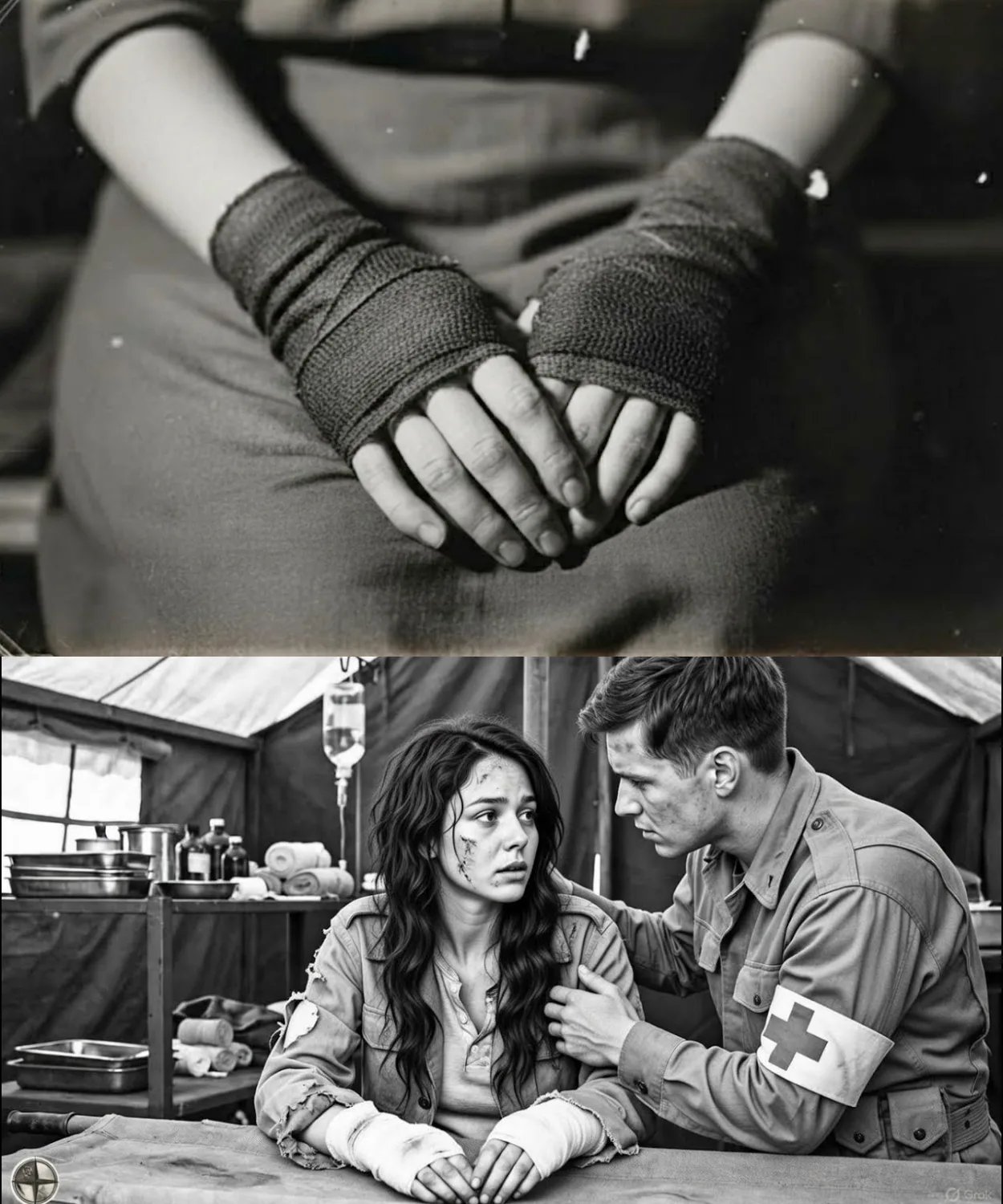

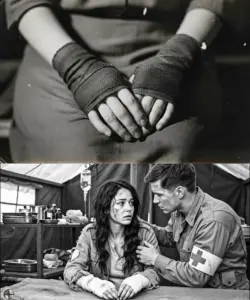

She was handed a canvas uniform and sent to a makeshift military hospital carved into the shell of a former textile factory.

There, beneath hanging bulbs and the wreak of bleach.

She scrubbed blood from stretchers and rung sweat from sheets soaked in morphine and fever.

She remembered the eyes most of all.

Boys no older than her brother.

blank eyed, shivering, already halfway gone.

She changed bandages and carried buckets and learned to step over puddles of vomit without flinching.

The older nurses moved like shadows, their faces thin and tight.

When one of them collapsed from exhaustion, a sergeant slapped her hard across the mouth and ordered her back to her feet.

“Endurance is honor,” he barked.

And Connor believed it.

She had to.

She couldn’t afford the heresy of doubt.

The air raids came in waves, sirens wailing, the sky splitting open, the thrum of engines above like a thousand beating drums.

She would crouch under the metal examination table, eyes shut, hands over her ears, the ground trembling beneath her.

Afterward, they picked through the rubble, looking for supplies, for bodies, for anything still useful.

Once she found half a photograph, the corner of a baby’s face, smiling in black and white.

She didn’t tell anyone.

She folded it into the cuff of her sleeve and carried it like a talisman.

Rumors moved like smoke through the hospital halls, of American prisoners tortured, of civilians shot on site, of women captured, defiled, erased, no one spoke them aloud in front of officers.

But at night, when the generators dimmed and the air grew still, the whispers slithered out.

They use women like dogs.

They cut off hands to make them talk.

They laugh while they do it.

Kaa listened.

She said nothing, but she stored each word, each warning in the hollow space behind her ribs where belief lived.

When the flyers fell from the sky, crude Japanese printed on American paper, promising safety and food if they surrendered, she helped burn them.

The propaganda was obvious, her commander had said.

a trick.

Connor watched the leaflets curl in flame, ink blackening, edges crumbling, and told herself she’d never need them anyway.

Then came August, a silence unlike any before.

The emperor’s voice on the radio, distant, trembling, saying things no one understood.

We must endure the unendurable.

Officers stopped shouting.

Orders stopped coming.

One morning, the hospital staff were simply told to leave.

No explanation, just bags packed, girls herded into trucks, wheels rumbling toward the unknown.

She sat beside girls she barely knew, their heads bowed, fingers clenched around cloth bags or prayer beads.

One tried to jump from the truck.

She was dragged back in by her collar.

No one spoke after that, not until they reached the coast.

Not until they saw the Americans, so tall, so quiet, clipboards in hand instead of bayonets.

Connor stared at their boots and waited for pain.

But there was none, just a ship, a bed, a bowl of food.

And later, a man with rough hands and gentle eyes who told her, “You ain’t nobody’s slave.” It was then that the past cracked and the present impossibly began.

The ship that carried Kana away from everything she had ever known moved like a slow wound through water.

Each hour stretched longer than the last.

The air rire of diesel and salt and something metallic like rusted iron.

Below deck the bunks were stacked tight, the ceilings low, the light flickering as though afraid to settle.

Connor sat hunched on the bottom bunk, knees pulled to her chest.

the fabric of her worn uniform stiff with salt from the sea air.

No one spoke above a whisper.

The silence was not peace.

It was dread, an unnatural quiet that wrapped itself around the girls like a second skin.

Every clang of chain or creek of metal sent a jolt through Ka’s spine.

She kept waiting for shouting, for boots, for the snap of command, but it never came.

The American guards aboard the ship did not carry whips.

They handed out trays of food, clean water, even soap, and that, more than cruelty, unsettled her.

Each morning brought a routine that felt too calm, too rehearsed.

Connor didn’t trust it.

She chewed each bite of bread as if testing for poison.

She drank water slowly, eyes on the guards, waiting for the trick.

But none came.

The Americans didn’t lear.

They didn’t gloat.

They mostly ignored the girls altogether, moving with bore efficiency.

It confused her more than war ever had around her.

The others began to crack in different ways.

Some grew more silent, shrinking into themselves like pressed flowers.

Others whispered to each other at night, fragments of memory or myth.

>> [snorts] >> One girl, barely 15, wept when handed a cup of soup.

Another kept hiding her bread under the mattress, certain it would be taken back.

A few refused to eat at all, their mouths clamped shut in protest or fear.

Connor watched them, but said nothing.

Her voice had dried up somewhere between Nagoya and the coast.

She measured time by meals and movement, by the way the ocean heaved beneath her like a living beast.

When she closed her eyes, she heard the whisper of flames, the scream of sirens.

But when she opened them, there was only the gray steel of the ship and the steady clatter of footsteps above.

One night, a girl across from her began to scream.

Not words, just a long breaking sound that twisted the stomach.

The guards came, but they did not strike her.

One of them knelt, placed a blanket over her shoulders, and spoke in a voice Ka couldn’t hear.

The girl quieted.

Her sobs turned to hiccups.

Then she slept.

That moment rattled Kaa more than the scream itself.

She began to write names in her mind.

her brother, her mother, the neighbor who shared rice during the blackout, the boy she once saw cry when his dog was shot by a soldier.

She repeated them silently each night like prayer beads, afraid that forgetting them would mean forgetting herself.

But the sea kept moving.

The ship did not turn around.

Then, after what felt like a season, the steel sky broke open to reveal land.

America.

She had imagined smoke stacks and cages, factories hissing with cruelty.

But what she saw was green hills rolled like cloth, scattered with grazing cattle, wooden fences, windmills, a dirt road winding through yellow fields.

It looked more like a story book than a battlefield.

Kana pressed her forehead to the port hole.

She saw white houses with porches and men in broad-brimmed hats leaning against fence posts chewing straw.

She saw children on bicycles.

The ship docked not in a fortress, but in a quiet port where the docks smelled of wood, not smoke.

When they disembarked, the guards didn’t shout.

They handed the girls down the ramp like passengers, not prisoners.

Ka’s knees shook as she stepped onto the foreign earth.

No one hit her.

No one even raised their voice.

They were herded onto trucks.

She didn’t fight it.

She couldn’t.

Her body was too tired, and her mind her mind was unraveling in threads.

The more kindness she was shown, the more tightly she clung to the idea that it was all a trap.

Her belief had nowhere left to live, but it hadn’t yet died.

The truck passed under the open sky, the sun bright and unforgiving.

She squinted toward the horizon and saw them.

Ranches, stables, barbed wire that looked more like fencing than prison walls.

Cows wandered lazily through pastures.

A man on horseback raised a hand in a lazy wave as they passed.

Kaa didn’t wave back.

She sat in the truck bed with the other girls, wind tugging at her hair, watching a land that made no sense.

It was too calm, too alive, and somewhere deep in her chest, she felt it again.

The same crawling fear that had gripped her when the cowboy told her she wasn’t a slave.

This wasn’t paradise, but it wasn’t hell, either.

It was something worse.

It was proof that everything she had believed might have been a lie.

The bunk house smelled like wood, dust, and old wool.

The boards creaked softly under her weight as Kana stepped through the door, escorted by a soldier who barely looked at her.

He pointed once toward the corner and then walked away, leaving her in a room that looked more like a summer camp than a prison.

The walls were bare, the floor swept clean, and the windows, real windows, let in slices of evening sun that painted golden lines across the floorboards.

There were no locks on the doors, no shouting, no sirens, just a row of simple CS, each with a folded blanket and a tin cup placed neatly at the side.

Kana stood still for a moment, unable to make sense of the stillness.

It wasn’t right.

There was no punishment waiting behind the next breath.

No shame coiled in the corner, just space.

She moved slowly to the cot at the far end and sat down.

The mattress was thin but forgiving.

The blanket was heavy in her hands, real wool, not straw stuffed canvas like the one she’d known in the barracks.

Her body tensed automatically, waiting for the barked command, the slap across the face, the shame that always followed rest.

But no voice came, no boots stomped down the aisle.

No one cursed her for sitting before permission was given.

She looked down at the blanket, tracing its edges with her fingers.

It was gray blue, stiff with starch, but warm against her skin.

There was no name stitched into it, no government seal.

It belonged to no one, and yet somehow it had been given to her.

Back in Nagoya, the barracks were carved from rot and discipline.

They slept on wooden slats, shoulderto-shoulder, too cold to shiver and too scared to speak.

The blankets were threadbear and carried the scent of 10 others before her.

Sweat, blood, mildew.

If someone cried in the dark, the guards would strike the wall with their batons and shout them into silence.

Shame was law.

Weakness was contagious.

Rest was a privilege for the dead.

Here there was only the quiet crack of wood cooling in the rafters.

Kana lay down slowly, curling her knees to her chest, the blanket wrapped tight as a shell around her body.

Every muscle braced for the hand that would tear it away.

She had never had something of her own.

Not like this, not something soft, not something that did not demand repayment.

Her fingers clutched the edge until her knuckles achd.

She stared at the ceiling for what felt like hours, tracing the knots in the beams with her eyes.

Outside, crickets chirped.

Somewhere in the distance, a dog barked once.

No sirens, no weeping, no explosions.

She had no name for this silence.

It felt dangerous, like standing too close to the edge of a cliff.

Sleep came like a thief, not all at once, but in fragments, her breath slowing, her grip on the blanket loosening, the weight of exhaustion dragging her under.

And for the first time in what might have been years, she did not dream of fire.

When she woke, the blanket was still there.

She sat up, blinking at the morning, light filtering through the window.

The room was the same.

No one had taken it.

No one had screamed at her.

She touched her face, her arms, her ribs.

Everything was intact.

Her body felt heavier.

Not from food, she hadn’t eaten enough yet for that, but from something else.

from the shock of being allowed to exist without condition.

And then the thought came, sudden and cruel.

If this is how the enemy treats me, then who have I been fighting for? It wasn’t a full betrayal of everything she had believed, but it was the beginning of the fracture, the first real crack.

She had been taught that Americans were brutes, that their kindness was a trick, their food bait, their smiles camouflage.

But she had not been bribed.

She had not been touched.

She had simply been let be.

As she folded the blanket and placed it back on the cot, something in her moved, not forward, not yet, but away from the certainty that had once made her feel safe.

She stood slowly as if testing gravity itself.

And when the door opened and the guard from the day before offered her a cup of something hot, she took it with both hands.

He nodded.

She didn’t smile, but she didn’t look away either.

And in that smallest moment, a war ended.

Not the one between nations, but the one inside her chest.

The tin plate was warm in her hands, almost too warm.

Kaa stared down at it, the surface fogged with steam that curled like smoke from some sacred fire.

Chunks of meat floated in thick brown stew, speckled with carrots and soft potatoes.

The smell hit her before she could steal herself.

Rich, savory animal.

Her stomach growled loudly, betraying her.

She hadn’t eaten something this nourishing in months.

Not since before the raids.

Not since before the rice rations turned to water, and her body began to eat itself from the inside out.

Her fingers trembled slightly as she gripped the edge of the plate.

A wooden bench sat waiting.

Others were already seated, girls she recognized from the truck ride, each with the same wide, weary eyes.

No one spoke.

No one smiled.

They ate in silence, chewing slowly as if trying to remember how.

Kaa sat down at the end of the bench, legs stiff.

She looked again at the food, then at the cowboy standing near the door.

The same man from before, the one she had clung to like death.

He nodded at her once, not like a superior, like a neighbor, then turned and walked away.

Her eyes burned.

She lifted the spoon slowly, hesitantly, as if expecting a slap to follow.

But the pain never came.

The spoon dipped into the stew.

It was thick, heavy, real.

She brought it to her lips.

Her mouth opened before she could stop it.

The first taste was fire and salt and fat.

Her throat choked reflexively, but she swallowed.

And with that one swallow, her body overruled her brain.

Spoon after spoon, she shoveled it in, barely tasting, tears leaking down her face as shame surged through her chest.

Her hands didn’t stop.

Her mind screamed, “Tiateritor, weakling, slave.” But her body had no room for ideology anymore.

It only understood hunger, the kind that drills into bone and turns morals into ash.

Each bite was a confession.

She sobbed quietly, hunched over her food like an animal.

Not because it tasted good, though it did.

Not because she was grateful, though some part of her was.

She cried because every warm swallow felt like surrender, like she was letting go of a part of herself she was supposed to protect.

Her tears fell into the stew.

She didn’t stop eating.

The girl across from her glanced up, eyes red- rimmed but dry.

She didn’t speak either.

None of them did.

Words would have made it real.

Words would have made it betrayal.

Instead, they ate in silence, their spoons clinking softly against the metal plates in a rhythm that sounded almost like mourning.

When Ka finally set her spoon down, the plate was nearly clean.

Her stomach achd from fullness, something she hadn’t felt in nearly a year.

The blanket was still wrapped around her shoulders, her fingers still gripped the edge of the tin, even though there was nothing left inside.

She sat still, breathing slowly, like someone who had just survived something invisible.

The cowboy returned a few minutes later.

He didn’t speak, just walked between the benches, collecting the plates.

When he reached Kana, he paused, their eyes met.

She expected a smirk, some sign of triumph, but he only nodded again and took the plate gently from her hands.

Then, as he turned, he murmured something so low she almost missed it.

“Glad you ate.” “Not good, girl.

Not finally, just glad.” Connor blinked.

He wasn’t mocking her.

He wasn’t watching her to make sure she finished.

He wasn’t performing mercy like a man trying to be forgiven.

He had meant it.

And that that shook her more than the stew, more than the softness of the cot, more than the silence of the ranch.

She didn’t understand this kind of kindness, kindness without condition, kindness without performance.

She had been trained to see the enemy as monstrous.

Now she couldn’t tell if the real monster was the man before her, or the idea she had clung to for so long.

The warmth in her belly turned to nausea, not from the food, from the fear that maybe, just maybe, they hadn’t been lying.

Maybe the enemy didn’t look like a cowboy with soft eyes.

Maybe the enemy had been behind her all along.

The pencil felt foreign in her fingers, not because she hadn’t held one before.

She had plenty of times back in school, back before the walls cracked and her world collapsed.

But because this one had no weight of fear behind it, no lesson to recite, no officer hovering overhead, it wasn’t thrust into her hand as an order, it was offered quietly, freely.

“Write,” the translator said in slow Japanese.

“To your family, if you want.” Ka looked up, eyes narrowing.

She hadn’t heard her native language spoken gently in months.

Her instinct screamed trap.

Why would the enemy let her write home? What would they do with the letter? Would they laugh at it, burn it, use it to trace her family and punish them? Still the pencil remained, and the lined paper lay before her like a blank sky.

She hesitated, then took both.

Her hand shook.

She had no address, no certainty her family was alive, no faith that this message would ever be read by anyone.

She stared at the empty page for a long time.

Then, in slow, practiced strokes, she wrote a single line.

Watashiakunai, I am not in pain.

She paused.

That was all.

That was enough.

Her throat achd with the unshed tears of saying too little and far too much.

She folded the letter and handed it back.

No one inspected it.

No one scolded her for wasting space.

They just took it and said they would send it.

For a full day she waited for punishment, waited for someone to mock her handwriting or accuse her of hiding code.

But it never came.

The world went on.

The crickets chirped.

The sky blazed blue.

The stew arrived on time.

Later that week, she found herself sweeping the bunk house steps.

It wasn’t an assigned task.

She just needed something to do with her hands.

The wind had scattered dust across the floorboards, and it felt wrong to leave it.

Her body had grown used to labor, and rest still felt too loud.

That’s when he appeared again.

the cowboy with the dustcoled hat and the patient eyes.

He leaned against the porch post, watching her for a moment before speaking.

His words were slow and thick, and she understood none of them, but his tone was soft.

He pointed to the broom.

“Okay,” he said, tapping his chest lightly.

“Okay.” Ka froze.

He repeated it, smiling faintly, then again, pointing at her.

Okay.

She blinked.

Was this a question, a reassurance, a command? The word sounded simple, gentle, like the brushing of leaves.

He mimed, sweeping, nodded.

Okay.

And then he walked off.

That night she whispered the word to herself as she lay beneath the heavy blanket.

Okay.

The sound rolled oddly in her mouth.

not sharp, not clipped like Japanese syllables, open, airy, like something incomplete but not broken.

She didn’t know what it meant exactly, but she knew how it felt.

It felt possible.

The next morning, she whispered it again when the sky turned pink.

Okay, just to see if the world would accept it.

It did.

The American word didn’t mean surrender.

It didn’t mean loss.

It meant something else.

Something softer, a kind of truce between fear and hope.

She began collecting more words without realizing it.

Milk, blanket, thank you.

But okay, was the one that stayed close to her chest.

It was her secret, her shield, her stepping stone into a world that didn’t hurt when you touched it.

She didn’t smile when she said it.

Not yet.

But one day she might.

For now, okay was enough.

The first time she heard music, it didn’t sound like anything from the world she remembered.

It wasn’t ceremonial like the thrum of drums during school assemblies or the solemn singing at temple.

It wasn’t broadcast war anthems or marching bands on the loudspeakers.

It was something else, loose, strange, soft.

The sound drifted from the far end of the camp one late afternoon, carried by the wind and the lazy hum of a nearby radio.

Connor had been folding laundry on a low bench, watching her fingers move like they belonged to someone else.

She didn’t notice it at first, the twang of strings, the tapping rhythm, the uneven hum of a man’s voice, half singing, half speaking in English.

But as it grew louder, she paused.

Something stirred in her chest, not memory, not recognition, just warmth.

A cowboy appeared near the messaul, cradling a wooden instrument, its long neck curved and worn with use.

He strummed it without urgency, plucking at the strings as if teasing the air.

A few soldiers gathered around, not in formation, but in comfort, heads bobbing, boots tapping lightly in the dust.

No one barked orders.

No one saluted.

They just listened.

Another soldier leaned back in his chair and pulled a harmonica from his pocket.

He played a few sharp notes, then laughed and shook his head, making fun of his own clumsy attempt.

The banjo player grinned and nodded toward Kana.

“Give it a try,” he said softly, holding the harmonica out in her direction.

Kana froze.

She looked from the harmonica to his face, searching for mockery, but there was none, just quiet invitation.

Hesitantly she stepped forward.

Her hands reached out before her mind caught up.

The metal was cool and smooth, slightly dented at the edge.

She had no idea what to do with it.

It looked like something a child might play with.

“Just blow,” the cowboy said, tapping his chest.

“Okay, that word again.

” She pressed the instrument to her lips and blew.

A soft, unsure note escaped.

It wobbled in the air, awkward and imperfect, but it was sound.

It was hers.

The soldiers clapped politely, and the man with the banjo gave her a thumbs up.

She stepped back, eyes wide, cheeks flushed.

Later that night, she sat by the edge of the bunk house, watching the sun bleed orange across the fields.

Her fingers curled around the harmonica, which the cowboy had let her keep.

She blew another note, then another.

The breeze answered her in size of grass, and then, like a match, struck too close to a wound, it happened.

Laughter, it broke from her throat without warning.

A quiet, breathy chuckle, so small she could have denied it.

But it grew.

It slipped out again, sharper, less restrained.

Her hand flew to her mouth as if to catch it, shove it back in.

But it was too late.

She was laughing.

Not because something was funny, not because she was joyful, but because something inside her cracked wide open.

The sound felt alien in her ears, like hearing a voice you forgot you had.

It was thin, awkward, but real.

The last time she had laughed was with her father in the garden pulling weeds just days before the bombings.

He had told a joke about the neighbor’s cat, something silly, forgettable.

She remembered the way his eyes crinkled, how he patted her head, saying she laughed too loud for such a small girl.

That man was gone.

The house was gone.

The war had burned the joke to ash.

But here, beneath a sky that didn’t carry planes, with dust on her shoes and a harmonica in her lap, she laughed again.

And it terrified her, because laughter meant permission.

It meant letting go.

It meant that some part of her was beginning to believe in this new world, even as the old one clung to her ribs like a ghost.

She wiped her eyes, unsure if they were tears of joy or betrayal.

But the harmonica stayed in her pocket, and when the cowboy passed by and tipped his hat, she didn’t flinch.

She nodded and whispered, “Okay.” It started with a saddle, brown leather worn at the seams, with a faint scent of dust and sweat.

The cowboy who once held her trembling hands now stood beside her, one boot resting on the wooden fence, gesturing toward the tall chestnut mare beyond it.

Kaa had never been near a horse.

Not really.

In Japan, horses were distant things, part of parades, symbols in textbooks, not companions, not something you were invited to ride.

The cowboy smiled and patted the saddle.

You’re ready, he said.

Not in Japanese, just in that slow, steady draw that was beginning to make sense without translation.

She didn’t respond, not out loud, but her hand reached for the wood rail, and she hoisted herself up, legs wobbling slightly, heartbeat pounding.

The mayor didn’t flinch.

Neither did he.

As the days passed, Ka found herself doing more than just existing.

She helped water the animals.

She carried hay.

She walked the perimeter fence with other girls, their silence no longer heavy, but shared.

The work didn’t feel like labor.

It felt like proof.

Proof that her body was still strong, that she had survived something vast, and that survival itself wasn’t shameful.

The cowboy, whose name she had finally learned, Rey, spoke little, but with intent.

When she asked haltingly why he was so kind, he only shrugged and said, “You’re a person.

Ain’t that reason enough?” It was such a simple sentence, but to Kaa it landed like thunder.

Back home, she had been a piece of the machine, a girl with soft hands, trained to bind wounds and stitch what bullets tore open.

Her country had told her she was sacred, valuable.

But only if she obeyed, only if she died before dishonor.

When she survived, when she surrendered, she had expected punishment from the enemy.

But instead, here she was learning to ride, to speak, to laugh.

And so the question began to gnaw at her in the quiet moments.

If my enemies treat me like I matter, then why didn’t my own country? Bushido had taught her that honor came from death, from obedience, from silence.

But Rey didn’t ask for any of those things.

He asked if she wanted seconds.

He told her stories about his dog back home.

He let her wear his spare gloves when the morning frost bit too sharp.

One day, after she had managed to trot without slipping from the saddle, she slid off the horse and grinned breathless.

Ry caught the rains and gave her a short impressed nod.

“You ain’t weak, you know,” he said.

“Take strength to stay.” She stood still, the smile fading.

His words cut deeper than any insult ever had because in them she heard the truth she had never been allowed to believe.

She wasn’t a coward.

She was a survivor.

She didn’t bow.

She didn’t thank him.

She just looked at the sky clear and cold and let the truth settle like sun on her shoulders.

The ideology that once shaped her had begun to crack days ago, but now it fell in on itself completely.

Bushido hadn’t saved her.

It had nearly killed her.

What saved her was warmth, laughter, a bowl of stew, a man in a hat who saw her as something more than a piece of a lost empire.

She touched the harmonica in her pocket.

The camp was not home.

It never would be.

But here, for the first time in her life, she felt worthy.

If this story moves you, please like the video and leave a comment below telling us where in the world you’re watching from.

We’d love to hear your thoughts.

It was a quiet morning, the kind where the sky looked painted and the breeze came soft, smelling of hay and river water.

Connor had finished feeding the chickens and was wiping her hands on her skirt when she heard the giggle.

A high sweet sound so out of place in a war camp that it almost startled her.

A little girl stood by the fence, sunlight tangled in her blonde curls.

In her tiny hand, she held something red, bright red, vivid against the dust and denim.

Without a word, the girl stepped closer and reached up, placing the ribbon in Kaa’s palm.

Her fingers were small and warm.

“For you,” the girl said in the careful English that Kaa could now just barely follow.

Then she skipped off toward the mess hall, boots too big and hair bouncing behind her.

Kaa stood frozen.

The ribbon was silk, frayed at the edges, but still soft.

a deep red.

Not the crimson of flags or blood, but the red of apples, of childhood dresses, of festival lanterns swaying on summer nights.

She hadn’t worn anything colorful since before the bombings.

She hadn’t been anything but a soldier, a nurse, or a ghost since before the bombings.

hands trembling slightly, she reached up and tied the ribbon into her hair, not tight like a uniform knot, loose, free, letting the ends flutter in the wind.

She didn’t look around to see who was watching.

For once, she didn’t care.

When she passed the bunk house mirror that afternoon, a piece of tin nailed to a post, she caught her own reflection and stopped.

She looked like a girl again.

Not a prisoner, not a number, not a ghost of an empire’s pride, just a girl.

The realization nearly brought her to her knees.

Later, as she sat near the corral, brushing the mayor’s coat, she thought about her sister back in Nagasaki.

They used to tie ribbons into each other’s hair before school, laughing when one knot came out crooked.

She hadn’t let herself remember those mornings.

Memory had felt like betrayal, but now it felt like survival.

The ribbon had become more than cloth.

It was a symbol of something she hadn’t dared hope for.

Choice.

To wear red was to claim space.

To accept a gift without suspicion was to trust.

To tie something beautiful in her hair was to say, “I am still here.” The cowboy passed by later and noticed.

He didn’t comment.

He just tipped his hat and gave a quiet smile.

But it meant everything.

The ribbon drew no orders.

It wasn’t earned through combat or assigned by rank.

It wasn’t given in pity.

It was offered in kindness, in recognition.

And in that small silent gesture, something shifted permanently inside Kaa.

She no longer walked with her eyes down.

She no longer apologized for her presence.

She had once thought dignity came from sacrifice, that to be honorable was to be invisible, obedient, erased.

But now she saw it differently.

Dignity was choosing to laugh even after everything.

Dignity was eating, speaking, brushing your hair.

Dignity was tying a red ribbon where the world could see and letting it fly in the wind without shame.

She had not escaped war.

She had not returned home, but she had returned to herself.

And that, after all she had lost, was a victory, one she wore with pride, looped in red silk above her ear.

The trucks arrived just after dawn.

Their engines grumbled low like they didn’t want to wake the camp.

Ka stood near the fence, arms crossed loosely over a clean shirt, the red ribbon still tied in her hair.

around her.

Other girls whispered and packed, eyes darting with a strange mix of fear and relief.

Repatriation, they’d called it.

Return.

A word that once might have meant salvation now carried the weight of uncertainty.

She was going home, but she no longer knew what home meant.

A sergeant called her name.

She stepped forward, her bag light, her body heavier than it had been in years.

Her bones no longer jutted out like broken branches.

Her cheeks had softened.

Her shoes fit.

She had been given a new coat.

In her pocket was a letter folded twice, pressed flat.

She had written it the night before by lantern light, not sure if she’d ever send it.

It simply said, “I survived and I was kind.

That is enough.

Ry stood by the loading ramp, arms folded, hat tilted low against the rising sun.

He looked older that morning.

Or maybe she had just grown up.

For a moment, neither of them spoke.

Then, with the ease of habit, he reached up and touched the brim of his hat.

Kaa stepped forward.

She bowed, not deeply, not stiffly, but slowly.

not in obedience, not as a soldier, but as a woman offering respect.

It was the first time she had bowed that way since childhood.

He nodded back, a quiet smile tugging at his mouth.

“You be okay,” he said.

She understood him, and this time she believed it.

The ride to the port was long.

Dusty roads turned to pavement, and the sky grew heavier with clouds.

She didn’t cry, not because she wasn’t sad, but because there was nothing to mourn.

What had happened here wasn’t something she lost.

It was something she found.

When the ship pulled from the dock, she stood at the railing, watching the American coast slip into mist.

Behind her was a country that had once been the enemy.

But somewhere in that land was a bunk house with a tin mirror, a harmonica resting on a shelf, and a cowboy who had never once called her prisoner.

Back in Japan, the streets were rubble, her family scattered, her old neighborhood flattened.

But Ka returned not as the girl who had left, hollowed out by duty and fear.

She returned as a survivor who had found something precious in the most unexpected place, her own worth.

Years passed.

She married, had children, grew old, but the ribbons stayed, tucked inside a wooden box beside the harmonica.

On summer nights, when the air felt like Texas, and the stars looked big enough to ride, she’d sit with her grandchildren and tell stories that no one else dared speak.

I once met a man, she’d whisper, brushing the hair from her granddaughter’s forehead, who freed me by refusing to own me.

And they would ask, “Was he a soldier?” She’d smile and shake her head.

“He was a cowboy.” The past didn’t vanish.

It didn’t heal clean, but it softened at the edges.

It folded into memory, stitched together by kindness, laughter, and red silk.

Kaa was not erased by war.

She was rewritten by mercy.

If this story touched you, please like the video and let us know where in the world you’re watching from.

Thank you for remembering a story history almost forgot.